Chapter 24 Introduction

Late Adulthood: Cognitive Development

- The Aging Brain

- New Brain Cells

- Senescence and the Brain

- Information Processing After Age 65

- Input

- Memory

- Control Processes

- A VIEW FROM SCIENCE: Cool Thoughts and Hot Hands

- Output

- OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES: How to Measure Output

- Neurocognitive Disorders

- The Ageism of Words

- Mild and Major Impairment

- Prevalence of NCD

- Preventing Impairment

- Reversible Neurocognitive Disorder?

- A CASE TO STUDY: Too Many Drugs or Too Few?

- New Cognitive Development

- Erikson and Maslow

- Learning Late in Life

- Aesthetic Sense and Creativity

- Wisdom

698

699

WHAT WILL YOU KNOW?

- How does the brain simultaneously grow and shrink in old age?

New neurons develop in the adult brain particularly in two specific areas: The olfactory region and the hippocampus. Dendrites grow on existing neurons. However, growth in the brain in late adulthood is slow and limited, and not sufficient to restore the aging brain to its earlier state. In every part of the brain, the volume of gray matter is reduced, in part because the cortex becomes thinner with every decade of adulthood. White matter is generally reduced as well.

- What kinds of memory are least apt to fade in old age? What kinds are the most apt to fade?

Implicit memories (recognition and habits) are least apt to fade in old age. Explicit memories (recall of learned material) are most apt to fade.

- What is the difference between these four terms: Alzheimer, senility, dementia, and neurocognitive disorders?

Senile means “old,” but senility is used to mean severe mental impairment. Dementia is a precise term for irreversible, pathological loss of brain functioning. Neurocognitive disorders (NCD) is the DSM-

5 term for dementia, and includes a major or a mild version, plus the opportunity for early detection and treatment of cognitive decline. Alzheimer disease is a specific type of NCD characterized by brain atrophy, plaques, and tangles. - What gains in cognition occur in late adulthood?

According to many developmentalists, new depth, enhanced creativity, and even wisdom are possible gains in cognition in late adulthood.

I have eaten many dinners sponsored by large organizations. I am tired of them. No longer do I enjoy church suppers with lasagna and Jell-

But recently hundreds of other people and I attended an organization’s dinner that was unlike the rest. The appetizer was a cold kale and nut salad; the fish entrée was passed around family style; and the guests were mostly young, lean, and earnest. It was a celebration of 40 years of a group that works for pedestrian safety, protected bike lanes, and metered parking. Most of the patrons arrived by foot, subway, or bicycle.

This chapter on cognition in late adulthood begins with this event because each generation has its own concept of how things should be. Challenging our conceptions is one of the things people of other ages do for us.

My assumptions were challenged and my ideas grew, not only by the menu but also by the conversation and the speeches. Piaget thought intelligence was the ability to expand the mind whenever disequilibrium requires new thinking. Of course, Piaget’s fourth and final major intellectual expansion was formal operational thought during adolescence. But his insight applies to late adulthood as well: New experiences require deeper, better thinking. That is what research on the brain suggests.

I have not changed my basic values, but that dinner did expand my understanding. Cognitive development is a lifelong process, propelled by new experiences and reassessments.

This chapter describes the many intellectual losses of late adulthood in sensory input, memory, and output. But there are gains as well, including gains in thought and expression. You will also learn about neurological diseases that become more frequent as people grow older, including Alzheimer disease. Understanding them will entail some disequilibrium as you read: Many people have distorted ideas about aging, as is evident from the use of “senility,” a word that itself is a distortion.

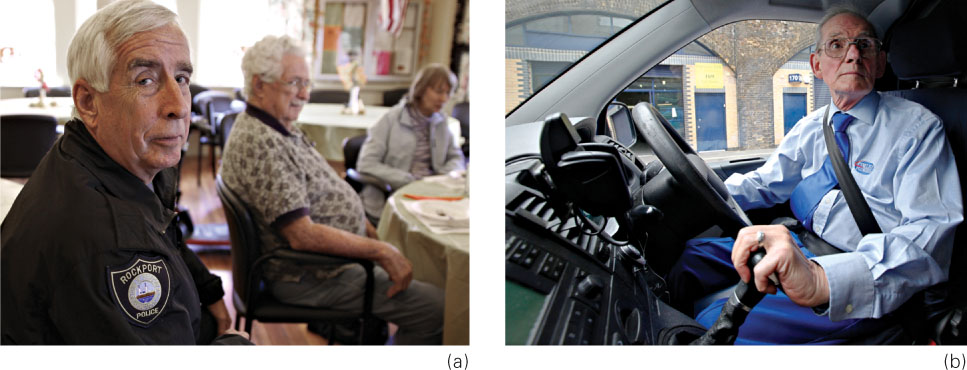

One theme is evident throughout: Older people can become wiser, but they do not always do so. Intellectual prowess after age 65 requires that people attend to aspects of life that require new concepts or skills. As you will see, this may include playing video games, or lifting weights, or storytelling, or painting, or singing, or staying on the job. For me, it included going to dinner.

700

© SUZANNE PLUNKETT/REUTERS/CORBIS