25.1 Theories of Late Adulthood

Development in late adulthood may be more diverse than at any other age: Some elderly people run marathons and lead nations; others no longer walk or talk. Social scientists theorize about these variations.

Self Theories

self theories Theories of late adulthood that emphasize the core self, or the search to maintain one’s integrity and identity.

Some theories of late adulthood are self theories; they focus on individuals’ self-

The Self and Aging

Perhaps people become more truly themselves as they grow old, as Anna Quindlen found:

It’s odd when I think of the arc of my life from child to young woman to aging adult. First I was who I was, then I didn’t know who I was, then I invented someone and became her, then I began to like what I’d invented, and finally I was what I was again. It turned out I wasn’t alone in that particular progression.

[Quindlen, 2012, ix]

Older adults need to maintain their self-

A central idea of self theories is that each person ultimately depends on himself or herself. As one woman explained:

I actually think I value my sense of self more importantly than my family or relationships or health or wealth or wisdom. I do see myself as on my own, ultimately…. Statistics certainly show that older women are likely to end up being alone, so I really do value my own self when it comes right down to things in the end.

[quoted in J. Kroger, 2007, p. 203]

Integrity

integrity versus despair The final stage of Erik Erikson’s developmental sequence, in which older adults seek to integrate their unique experiences with their vision of community.

The most comprehensive self theory came from Erik Erikson. His eighth and final stage of development, integrity versus despair, occurs when adults seek to integrate their unique experiences with their vision of community (Erikson et al., 1986). The word integrity is often used to mean honesty, but it also means a feeling of being whole, not scattered, comfortable with oneself.

As an example of integrity, many older people are proud of their personal history. They glorify their past, even when it includes events such as skipping school, taking drugs, escaping arrest, or being physically abused. Psychologists sometimes call this the “sucker to saint” phenomenon—that is, people interpret their experiences as signs of their nobility (saintly), not their stupidity (Jordan & Monin, 2008).

731

As Erikson explains it, such self-

life brings many, quite realistic reasons for experiencing despair: aspects of the present that cause unremitting pain; aspects of a future that are uncertain and frightening. And, of course, there remains inescapable death, that one aspect of the future which is both wholly certain and wholly unknowable. Thus, some despair must be acknowledged and integrated as a component of old age.

[Erikson et al., 1986, p. 72]

Integration of death and the self is an important accomplishment of this stage. The life review and the acceptance of death (explained in the Epilogue) are crucial aspects of the integrity envisioned by Erikson (Zimmerman, 2012). [Lifespan Link: The life review was discussed in Chapter 24.]

Self theory may explain why many of the elderly strive to maintain childhood cultural and religious practices. For instance, grandparents may painstakingly teach a grandchild a language that is rarely used in their current community, or encourage the child to repeat rituals and prayers they themselves learned as children. In cultures that emphasize newness, elders worry that their values will be lost and thus that they themselves will disappear.

As Erikson (1963) wrote, the older person

knows that an individual life is the accidental coincidence of but one life cycle with but one segment of history and that for him all human integrity stands or falls with the one style of integrity of which he partakes…. In such a final consolation, death loses its sting.

[Erikson, p. 268]

Holding On to the Self

Most older people consider their personalities and attitudes quite stable over their life span, even as they acknowledge physical changes in their bodies and gaps in their minds (Klein, 2012). One 103-

The need to maintain the self may explain behavior that seems foolish to some. For example, many elders hate to give up driving a car because “the loss felt, for men in particular, is deeper than that of simply not being able to get from A to B; it is a loss of a sense of self, of the meaning of manhood” (Davidson, 2008, p. 46).

Similarly, many older people refuse to move from drafty and dangerous dwellings into smaller, safer apartments because abandoning familiar places means abandoning personal history. Likewise, they may avoid surgery or reject medicine because they fear anything that might distort their thinking or emotions: Their priority is self-

compulsive hoarding The urge to accumulate and hold on to familiar objects and possessions, sometimes to the point of their becoming health and/or safety hazards. This impulse tends to increase with age.

The insistence on protecting the self may explain a behavior that many find pathological: compulsive hoarding, the urge to save papers, books, mementos, and so on. In a new chapter titled “Obsessive-

732

Socioemotional Selectivity Theory

socioemotional selectivity theory The theory that older people prioritize regulation of their own emotions and seek familiar social contacts who reinforce generativity, pride, and joy.

Another self theory is socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, 1993). The idea is that older people prioritize their emotional regulation, seeking familiar social contacts who reinforce their generativity, pride, and joy. As socioemotional theory would predict, when people believe that their future time is limited, they think about the meaning of their life. Then they decide that they should be more appreciative of family and friends, thus furthering their happiness (Hicks et al., 2012).

A slightly different version of the same idea comes from selective optimization with compensation, which you read about in Chapters 21 and 23. As senescence changes external appearance, older adults select the key aspects of themselves and optimize them. This is central to self-

positivity effect The tendency for elderly people to perceive, prefer, and remember positive images and experiences more than negative ones.

An outgrowth of both socioemotional selectivity and selective optimization is known as the positivity effect (Penningroth & Scott, 2012). Elderly people are more likely to perceive, prefer, and remember positive images and experiences than negative ones (Carstensen et al., 2006). Compensation occurs via selective recall: Unpleasant experiences are reinterpreted as inconsequential. People select positive emotions, perceptions, and memories.

For example, with age, stressful events (economic loss, serious illness, death of friends or relatives) become less central to one’s identity. That enables the elderly to maintain emotional health through positive self-

The positivity effect may explain why, in every nation and religion, older people tend to be more patriotic and devout than younger ones. They see their national history and religious beliefs in positive terms, and they are proud to be themselves—

Anna Quindlen was quoted just a few pages ago as saying she was glad she “was what I was again.” This trait has both positive and negative implications, as the following suggests.

733

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Too Sweet or Too Sad?

When I was young, I liked movies that were gritty, dramatic, violent. My mother criticized my choices; I told her I wanted reality. She liked romantic comedies that made her laugh; I told her that was frivolous.

Now my youngest daughter wants me to read dystopian novels in order to be aware of current culture. Hunger Games is an example. I tell her there is enough poverty and conflict in the world without having to read about imaginary killings. Notice the developmental shift. Is the positivity effect a distortion or a welcome perspective?

Many researchers have found that a positive worldview increases with age and that it correlates with believing that life is meaningful. Those elders who are happy, not frustrated or depressed, are likely to agree strongly that their life has a purpose (e.g., “I have a system of values that guides my daily activities” and “I am at peace with my past”) (Hicks et al., 2012). Meaningfulness and positivity correlate with a long and healthy life.

When a gamble doesn’t succeed, does frustration interfere with your judgment? If you are an emerging adult, the answer is often yes, but not if you are an older adult. The elderly are quicker to let go of disappointments, thinking positively about going forward. As a result, many studies have found “an increase in emotional well-

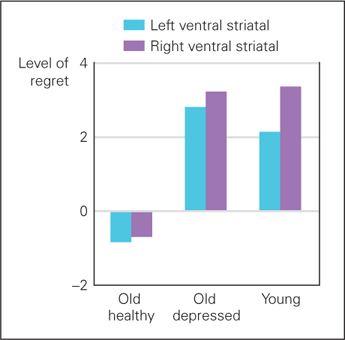

Researchers have measured reactions to disappointment, not only in attitudes and actions, but also in brain activity and heart rate. One study compared three groups: young adults, healthy older adults, and older adults with late-

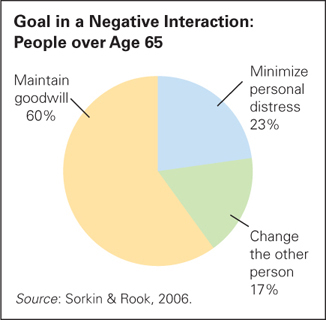

In another study, adults of several ages were asked to recall recent examples of personal confrontation and then to explain what they did, why, and how they felt later (Sorkin & Rook, 2006). Of those who were over age 65, many (39 percent) could not think of any confrontation. Among those who remembered conflicts, most of the elders, but not the younger participants, said that their primary goal was to maintain goodwill. Only a few of those over age 65 sought to change the other person’s behavior (see Figure 25.2).

734

Since their goal was to achieve harmony, the elderly were more likely to compromise instead of insisting that they were correct. This led to a happier outcome.

Participants whose primary coping goal was to preserve goodwill reported the highest levels of perceived success and the least intense and shortest duration of distress. In contrast, participants whose…goal was to change the other person reported the lowest levels of perceived success and the most intense and longest lasting distress.

[Sorkin & Rook, 2006, p. 723]

It could be argued that anger and frustration are useful emotions and that the positivity effect is too rosy, ignoring reality. It is distressing to try to change other people, but that doesn’t mean that people should accept whatever disturbs them. My daughter recently apologized for a criticism she had of me. I replied, honestly, that I had forgotten her critique.. My response might have made her frustrated. The positivity effect is not always appreciated.

However, having a positive outlook not only makes a person happier, but it also might avoid “lasting distress.” Was my mother right?

Stratification Theories

stratification theories Theories that emphasize that social forces, particularly those related to a person’s social stratum or social category, limit individual choices and affect a person’s ability to function in late adulthood because past stratification continues to limit life in various ways.

A second set of theories, called stratification theories, emphasizes social forces (1) that position each person in a social stratum or level and (2) that create disadvantages for people in some groups and advantages for people in other groups. Stratification begins in the womb, as “individuals are born into a society that is already stratified—

Stratification by Gender, Ethnicity, and SES

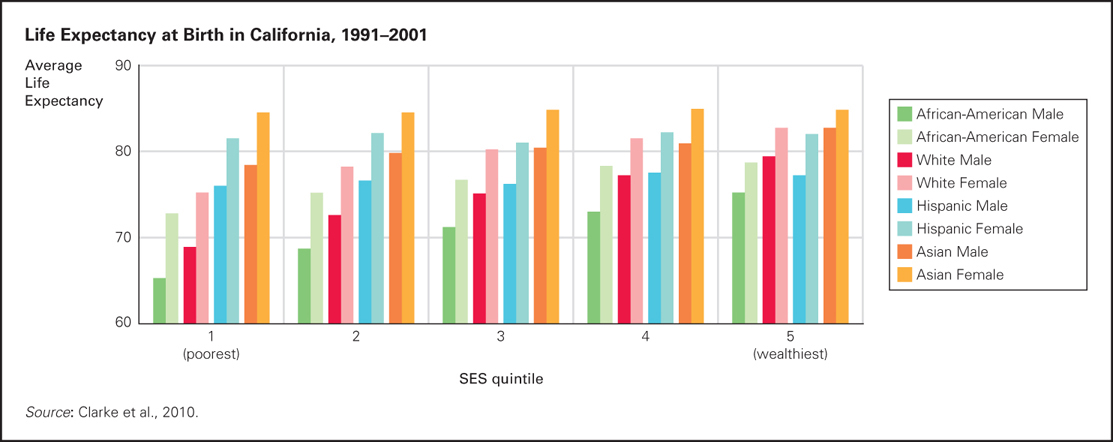

Observation Quiz Which group’s life span is most affected by poverty, and which is least affected?

Answer to Observation Quiz: White males the most, Asian females the least. There is much speculation as to why, but the data provide no answer.

Every form of stereotyping makes it more difficult for people to break free from social institutions that assign them to a particular path. The results are cumulative, over the entire life span (Brandt et al., 2012).

For instance, as described in many of the preceding chapters, children who are both African American and poor are more likely to be low birthweight, less likely to talk at age 1, less likely to read before age 6, more likely to drop out of school, less likely to obtain a college degree, less likely to be employed, less likely to marry, and finally, more likely to develop cancer, diabetes, and all other serious health problems. This is true when a child is compared to children of other ethnic groups, and when compared to other African American children who are not poor (see Figure 25.3).

Each stereotype adds to stratification and thus adds to the risk of problems, perhaps putting those who are female, nonwhite, and poor in triple jeopardy. However, you will see at the end of this section that not everyone agrees with that conclusion (Rosenfeld, 2012).

First consider gender. Irrational, gender-

In another example of gender stratification, young women typically marry men a few years older and then outlive them. Especially in former years, many married women relied on their husbands to manage money and to keep up with politics. Thus, past gender stratification led to decades of isolation, poverty, and dependence among the oldest-

Why do women outlive men? This could be biological, but it could result from lifelong stratification that works against males. Boys are taught to be stoic, repressing emotions and avoiding medical attention. In this way, both sexes may suffer from gender stratification, the men by dying too soon and the women by being widowed too long.

735

Ethnic stratification also harms people. For instance, past racism may cause weathering in African Americans, increasing allostatic load and shortening healthy life (Thrasher et al., 2012). The fact that health problems result from a lifetime of stratification “suggests multiple intervention points at which disparities can be reduced,” beginning before birth (Haas et al., 2012, p. 238). [Lifespan Link: Weathering is explained in Chapter 21 in the section Accumulating Stressors.]

Past ethnic discrimination also affects income in many ways. Consider home ownership, a source of financial security for many seniors. Fifty years ago, stratification prevented many African Americans from buying homes. Laws passed since then have reduced housing discrimination, but a disproportionate number of non-

A particular form of ethnic stratification affects immigrant elders. Many cultures expect younger generations to care for the elderly, but U.S. homes are designed for nuclear families. Pensions and Social Security are given to employees who worked for decades, which leaves many older immigrants (without U.S. work history) poor, lonely, and dependent on their children, who live in homes and apartments not designed for extended families and who themselves must contend with stereotypes about immigrants.

Finally, the most harmful effect of stratification may be financial, first the direct effects of poverty, then magnified by gender, ethnicity, and age. As one reviewer explains, “[W]omen…are much more likely to live in households that fall below the federal poverty line. Black and Hispanic women are particularly vulnerable” (J. S. Jackson et al., 2011, p. 93). One crucial factor is past employment. Many of the poorest elderly never held jobs that paid Social Security. Thus, an important source of income is absent. When ethnic discrimination affects employment opportunity, old-

Low-

736

The problem may begin even before birth, since epigenetic factors—

Stratification by Age

Ageism is, of course, stratification by age. Age affects a person’s life in many ways, including income and health. For example, seniority builds in the workplace, increasing income up to a certain point, and then employment stops, perhaps with a pension but never with as much income as before. People who are unskilled or temporary workers are particularly likely to be hurt by current old-

disengagement theory The view that aging makes a person’s social sphere increasingly narrow, resulting in role relinquishment, withdrawal, and passivity.

The most controversial version of age stratification is disengagement theory (Cumming & Henry, 1961), which holds that as people age, traditional roles become unavailable, the social circle shrinks, coworkers stop relying on them, and adult children turn away to focus on their own children. According to this theory, disengagement is a mutual process, chosen by both generations. Thus, younger people disengage from the old, who themselves voluntarily disengage from younger adults, withdrawing from life’s action.

activity theory The view that elderly people want and need to remain active in a variety of social spheres—

Disengagement theory provoked a storm of protest. Many gerontologists insisted that older people need and want new involvements. Some developed an opposing theory, called activity theory, which holds that the elderly seek to remain active with relatives, friends, and community groups. Activity theorists contended that if the elderly disengage, they do so unwillingly and suffer because of it (J. R. Kelly, 1993; Rosow, 1985).

Later research finds that being active correlates with happiness, intelligence, and health. This is true at younger ages as well, but the correlation between activity and well-

Especially for Social Scientists The various social science disciplines tend to favor different theories of aging. Can you tell which theories would be more acceptable to psychologists and which to sociologists?

Response for Social Scientists: In general, psychologists favor self theories, and sociologists favor stratification theories. Of course, each discipline respects the other, but each believes that its perspective is more honest and accurate.

Generally, happier and healthier elders are quite active—

Both disengagement and activity theories need to be applied with caution, however. Disengagement in one aspect of life (e.g., retirement) does not necessarily mean disengagement overall: Many retirees disengage from work but find new roles and activities (Freund et al., 2009). The positivity effect may mean that an older person disengages from emotional events that cause anger, regret, and sadness, while actively enjoying other experiences. Certainly some elders who never graduated from 8th grade are nonetheless vital pillars of their community.

Critique of Stratification Theories

Women, ethnic minorities, and low-

737

Both age-

Cautionary data about lifelong discrimination also comes from comparing ethnic groups. Although a Black/White disparity in survival and self-

Elderly Hispanics also seem to have a longevity advantage over elderly non-

SUMMING UP

Theories of development throughout the life span can apply to late adulthood as well as to earlier stages. Two sets of theories are particularly relevant to development in old age.

Self theories stress that people try to remain themselves, achieving integrity and not despairing, as Erikson explains. Other theories that can be considered self-

Stratification theories contend that social stereotypes continue lifelong, affecting the elderly by preventing financial independence and good health for reasons related to their gender, ethnicity, and past SES. Ageism adds to these other stereotypes. Disengagement theory suggests that the elderly relinquish past roles and withdraw from life. Activity theory holds the opposite idea, suggesting that societies should encourage activity in old age.