E.1 Death and Hope

A multicultural life-

One emotion is constant, however: hope. It appears in many ways: hope for life after death, hope that the world is better because someone lived, hope that death occurred for a reason, hope that survivors rededicate themselves to whatever they deem meaningful in life.

Cultures, Epochs, and Death

Few people in developed nations have witnessed someone die. This was not always the case (see Table EP.1). If someone reached age 50 in 1900 in the United States and had had 20 high school classmates, at least six of those fellow students would have already died. The survivors would have visited and reassured friends who were dying at home, promising to see them in heaven. Almost everyone believed in life after death.

762

|

Death occurs later. A century ago, the average life span worldwide was less than 40 years (47 in the rapidly industrializing United States). Half of the world’s babies died before age 5. Now newborns are expected to live to age 71 (79 in the U.S.); in many nations, centenarians are the fastest- |

| Dying takes longer. In the early 1900s, death was usually fast and unstoppable; once the brain, the heart, or any other vital organ failed, the rest of the body quickly followed. Now death can often be postponed for years through medical technology: Hearts can beat for years after the brain stops functioning, respirators can replace lungs, dialysis does the work of failing kidneys. |

| Death often occurs in hospitals. For most of our ancestors, death occurred at home, with family nearby. Now many deaths occur in hospitals, with the dying surrounded by medical personnel and machines. |

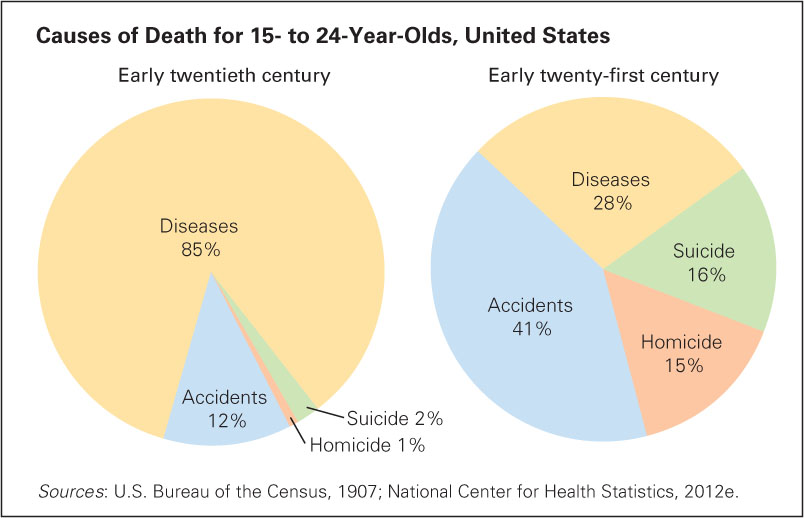

| The causes of death have changed. People of all ages once usually died of infectious diseases (tuberculosis, typhoid, smallpox), or, for many women and infants, in childbirth. Now disease deaths before age 50 are rare, and in developed nations most newborns (99 percent) and their mothers (99.99 percent) live. |

|

And after death… People once knew about life after death. Some believed in heaven and hell; others, in reincarnation; others, in the spirit world. Prayers were repeated— |

Now few die before old age, and if a young person dies, most often it occurs too quickly to say goodbye. Ironically, death has become more feared as dying has become less familiar (Carr, 2012). Accordingly, we begin by describing traditional responses when familiarity with death was common.

Ancient Times

Paleontologists believe that 100,000 years ago, the Neanderthals buried their dead with tools, bowls, or jewelry, signifying belief in an afterlife (Hayden, 2012). The date is controversial: Burial could have begun over 200,000 years ago or more recently—

The ancient Egyptians built magnificent pyramids, refined mummification, and scripted instructions (called the Book of the Dead) to aid the soul (ka), personality (ba), and shadow (akh) in reuniting after death so that the dead could bless and protect the living (Taylor, 2010).

The fate of dead Egyptians depended partly on their actions while alive, partly on the circumstances of death, and partly on proper burial. Death was a reason to live morally and to honor the past. If the dead were not appropriately cared for, the living would suffer.

Another set of beliefs comes from the Greeks. Again, continuity between life and death was evident, with hope for this world and the next. The fate of a dead person depended on past deeds. A few would have a blissful afterlife, a few were condemned to torture in Hades, and most would enter a shadow world until they were reincarnated.

Three themes are apparent in all the known ancient societies, not only in Greece and Egypt, but also in the Mayan, Chinese, Indian, and African cultures.

- Actions during life were thought to affect destiny after death.

- An afterlife was more than a hope; it was assumed.

- Mourners said particular prayers and made specific offerings, in part to prevent the spirit of the dead from haunting and hurting them.

763

Contemporary Religions

Now consider contemporary religions. Each faith seems distinct in its practices surrounding death. One review states: “Rituals in the world’s religions, especially those for the major tragic and significant events of bereavement and death, have a bewildering diversity” (Idler, 2006, p. 285).

Some details illustrate this diversity. According to one expert, in Hinduism the casket is always open, in Islam, never (Gilbert, 2013). In many Muslim and Hindu cultures the dead person is bathed by the next of kin; among some Native Americans (e.g., the Navajo) no family member touches the dead person. Specific rituals vary as much by region as by religion. In North America, Christians of all sects often follow local traditions. Similarly, there are more than 500 Indian tribes, each with its own heritage: It is a mistake to assume that Native Americans all have the same customs (Cacciatore, 2009).

According to many branches of Hinduism a person should die on the floor, surrounded by family, who neither eat nor wash until the funeral pyre is extinguished. By contrast, among some (but not all) Christians today, the very sick should be taken to the hospital; if they die, then mourners gather to eat and drink, often with music and dancing.

Diversity is also evident in Buddhism. The First Noble Truth of Buddhism is that life is suffering. Some rituals help believers accept death and detach from grieving in order to decrease the suffering that living without the deceased person entails. Other rituals help people connect to the dead as part of the continuity between life and death (Cuevas & Stone, 2011). Thus some Buddhists let the dying alone; other Buddhists hover nearby.

Religious practices change as historical conditions do. One example comes from Korea. Koreans traditionally opposed autopsies because the body is a sacred gift. However, Koreans value science education. This created a dilemma because medical schools need bodies to autopsy in order to teach. The solution was to start a new custom: a special religious service honoring the dead who have given their body for medical education (J-

Autopsies create problems in the United States as well. Autopsies may be legally required and yet be considered a religious sacrilege. For instance, for the Hmong in Cambodia, any mutilation of the dead body has “horrifying meanings” and “dire consequences for…the spiritual well-

Ideas about death are expressed differently in various cultures. For example, many people believe that the spirits of ancestors visit the living. Spirits are particularly likely to appear during the Hungry Ghost Festival (in many East Asian nations), on the Day of the Dead (in many Latin American nations), or on All Souls Day (in many European nations).

Consequently, do not get distracted by death customs or beliefs that may seem odd to you, such as mummies, hungry ghosts, reincarnation, or hell. Instead, notice that death has always inspired strong emotions, often benevolent ones. It is the denial of death that leads to despair (Wong & Tomer, 2011). In all faiths and cultures, death is considered a passage, not an endpoint, a reason for families and strangers to come together.

Understanding Death Throughout the Life Span

Thoughts about death—

764

Death in Childhood

Some adults think children are oblivious to death; others believe children should participate in funerals and other rituals, just as adults do (Talwar et al., 2011). You know from your study of childhood cognition that neither view is completely correct. Very young children have some understanding of death, but their perspective differs from that of older people. They may believe that the dead can come alive again. For that reason, a child might not immediately be sad when someone dies. Later, moments of profound sorrow might occur when reality sinks in, or simply when the child realizes that a dead parent will never again tuck them into bed at night.

Children are affected by the attitudes of others. If a child encounters death, adults should listen with full attention, neither ignoring the child’s concerns nor expecting adult-

Young children who themselves are fatally ill typically fear that death means being abandoned (Wolchik et al., 2008). Consequently, parents should stay with a dying child, holding, reading, singing, and sleeping. A frequent and caring presence is more important than logic. By school age, many children seek independence. Parents and professionals can be too solicitous; older children do not want to be babied. Often they want facts and a role in “management of illness and treatment decisions” (Varga & Paletti, 2013, p. 27).

Children who lose a friend, a relative, or a pet might, or might not, seem sad, lonely, or angry. For example, one 7-

Because the loss of a particular companion is a young child’s concern, it is not helpful to say that a dog can be replaced. Even a 1-

If a child realizes that adults are afraid to say that death has occurred, the child might decide that death is so horrible that adults cannot talk about it—

Remember how cognition changes with development. Egocentric preschoolers might fear that they, personally, caused death with their unkind words. [Lifespan Link: Egocentrism is discussed in Chapter 9.]

As children become concrete operational thinkers, they seek facts, such as exactly how a person died and where he or she is now. They want something to do: bring flowers, repeat a prayer, write a letter. The boy whose dog died went back to school after his parents framed and hung a poem he wrote to Twick. Children see no contradiction between biological death and spiritual afterlife, as long as adults neither lie nor disregard the child’s concerns (Talwar et al., 2011).

Death in Adolescence and Emerging Adulthood

Adolescents may be self-

765

“Live fast, die young, and leave a good-

terror management theory (TMT) The idea that people adopt cultural values and moral principles in order to cope with their fear of death. This system of beliefs protects individuals from anxiety about their mortality and bolsters their self-

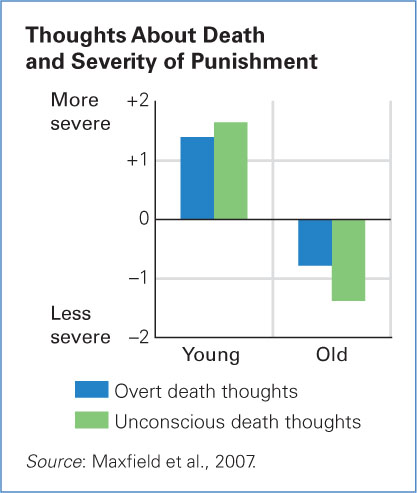

Terror management theory explains some illogical responses to death, including why young people take death-

Many studies have found that messages about the deadly consequences of smoking may provoke smokers to increase their consumption (Arndt et al., 2013). One study found that college students who were told that binge drinking is sometimes fatal were more willing to binge, not less so (Jessop & Wade, 2008). Thus teenagers and young adults may protect their pride and self-

Other research in many nations finds that when adolescents and emerging adults think about death, they sometimes become more patriotic and religious but less tolerant of other worldviews and less generous to people of other nations (Ellis & Wahab, 2013; Jonas et al., 2013). Apparently, people want to convince themselves that loyal, conscientious members of their own group (including themselves) are especially worthy of living.

Death in Adulthood

When adults become responsible for work and family, attitudes shift. Death is not romanticized. Many adults quit addictive drugs, start wearing seat belts, and adopt other death-

To defend against the fear of aging and untimely death, adults do not readily accept the death of others. When Dylan Thomas was about age 30, he wrote to his dying father: “Do not go gentle into that good night/Rage, rage against the dying of the light” (D. Thomas, 1957). Nor do adults readily accept their own death. A woman diagnosed at age 42 with a rare and almost always fatal cancer (a sarcoma) wrote:

I hate stories about people dying of cancer, no matter how graceful, noble, or beautiful…. I refuse to accept that I am dying; I prefer denial, anger, even desperation.

[Robson, 2010, pp. 19, 27]

When adults hear about another’s death, their reaction depends on the dead person’s age. Death in the prime of life is particularly disturbing. Michael Jackson and Whitney Houston were mourned by millions, in part because they were not yet old. Older entertainers who die are less mourned.

766

Reactions to one’s own mortality differ depending on the developmental stage as well. In adulthood, from ages 25 to 65, terminally ill people worry about leaving something undone or abandoning family members, especially children.

One dying middle-

Adult attitudes about death are often irrational. Logically, adults should work to change social factors that increase the risk of mortality—

For example, people fear travel by plane more than by car. In fact, flying is safer: In 2008 only 11 commercial airplanes crashed in the entire world, killing 587, but 84,000 people were killed by motor vehicles in the United States alone (U.S. Bureau of the Census, 2011b). Ironically, when four airplanes crashed on 9/11, 2001, many North Americans drove long distances instead of flying. In the next few months, 2,300 more U.S. residents died in car crashes than usual (Blalock et al., 2009). Not logical, but very human.

Death in Late Adulthood

In late adulthood, attitudes shift again. Anxiety decreases; hope rises (De Raedt et al., 2013). Life-

Some older people are quite happy even when they are fatally ill, which is beneficial. Indeed, many developmentalists believe that one sign of mental health among older adults is acceptance of mortality, which increases concern for others. Some elders engage in legacy work, trying to leave something meaningful for later generations (Lattanzi-

As evidence of this attitude change, older people seek to reconcile with estranged family members and tie up loose ends that most young adults leave hanging (Kastenbaum, 2012). Some people are troubled when their parents or grandparents allocate heirlooms, discuss end-

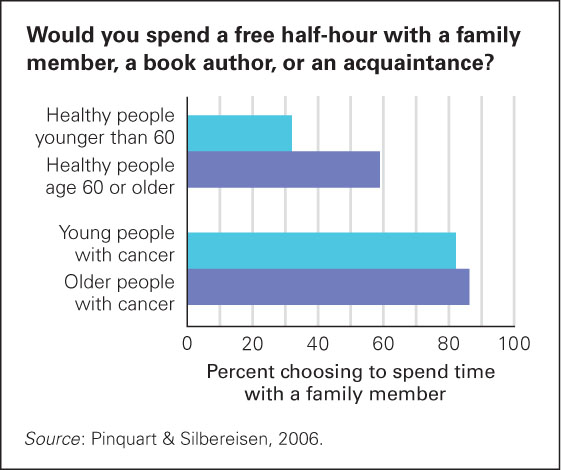

Acceptance of death does not mean that the elderly give up on living; rather, their priorities shift. In an intriguing series of studies (Carstensen, 2011), people were presented with the following scenario:

Imagine that in carrying out the activities of everyday life, you find that you have half an hour of free time, with no pressing commitments. You have decided that you’d like to spend this time with another person. Assuming that the following three persons are available to you, whom would you want to spend that time with?

767

- A member of your immediate family

- The author of a book you have just read

- An acquaintance with whom you seem to have much in common

Older adults, more than younger ones, choose the family member. The researchers explain that family becomes more important when death seems near. This is supported by a study of 329 people of various ages who had recently been diagnosed with cancer and a matched group of 170 people (of the same ages) who had no serious illness (Pinquart & Silbereisen, 2006). The most marked difference was between those with and without cancer, regardless of age (see Figure EP.3). Attitudes change when death becomes more salient.

Near-Death Experiences

Even coming close to death may be an occasion for hope. This is most obvious in what is called a near-

I was in a coma for approximately a week…. I felt as though I were lifted right up, just as though I didn’t have a physical body at all. A brilliant white light appeared…. The most wonderful feelings came over me—

[quoted in R. A. Moody, 1975, p. 56]

Near-

Most scientists are skeptical, claiming that

there is no evidence that what happens when a person really dies and “stays dead” has any relationship to the experience reported by those who have recovered from a life-

[Kastenbaum, 2006, p. 448]

Nevertheless, a reviewer of near-

Observation Quiz What three similarities do you see in these funerals?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Clothes, symbols, and ritual respect. In both, the mourners wear black, the coffins are draped with symbols (flags and flowers), and respect is conveyed in a manner appropriate for each—

JOHN TLUMACKI/THE BOSTON GLOBE VIA GETTY IMAGES

768

SUMMING UP

Before the twentieth century, everyone knew several adults who died young, and everyone had religious understandings of that event. Ancient cultures and current world religions have various customs about death, sometimes prescribing opposite actions. However, the general impact is to help survivors live better lives as they respond with hope. Age matters as well: Reaction to death depends partly on the developmental stage, with older adults less anxious about death than younger ones. Terror management theory finds that people sometimes react to death with defiance and intolerance. Near-