Grand Theories

In the first half of the twentieth century, two opposing theories—

Psychoanalytic Theory: Freud and Erikson

psychoanalytic theory A grand theory of human development that holds that irrational, unconscious drives and motives, often originating in childhood, underlie human behavior.

Inner drives, deep motives, and unconscious needs rooted in childhood are the foundation of psychoanalytic theory. These basic underlying forces are thought to influence every aspect of thinking and behavior, from the smallest details of daily life to the crucial choices of a lifetime.

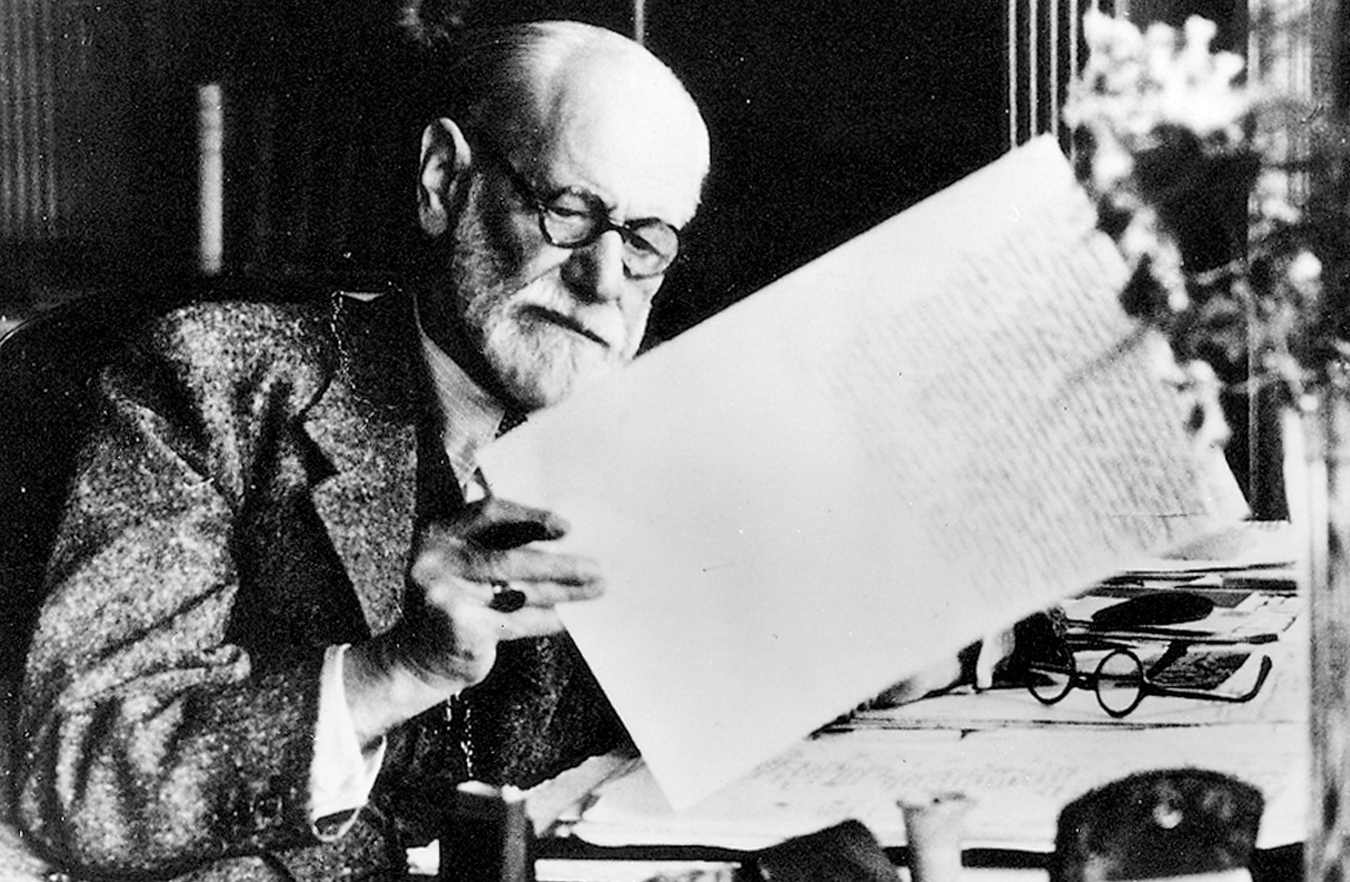

Freud’s Ideas

Psychoanalytic theory originated with Sigmund Freud (1856–

According to Freud, development in the first six years of life occurs in three stages, each characterized by sexual interest and pleasure arising from a particular part of the body. His theory of childhood sexuality was one reason psychoanalytic theory was rejected at first, because Victorian sensibilities arose from an opposite theory, that children were innocent, asexual beings, and that even in adulthood sexual passions were shameful.

According to Freud, in infancy the erotic body part is the mouth (the oral stage); in early childhood it is the anus (the anal stage); in the preschool years it is the penis (the phallic stage), a source of pride and fear among boys and a reason for sadness and envy among girls. Then, after a quiet period (latency), the genital stage arrives at puberty, lasting throughout adulthood. (Table 2.1 describes stages in Freud’s theory.)

| Approximate Age | Freud (Psychosexual) | Erikson (Psychosocial) |

|---|---|---|

| Birth to 1 year | Oral StageThe lips, tongue, and gums are the focus of pleasurable sensations in the baby’s body, and sucking and feeding are the most stimulating activities. | Trust vs. MistrustBabies either trust that others will satisfy their basic needs, including nourishment, warmth, cleanliness, and physical contact, or develop mistrust about the care of others. |

|

1- |

Anal StageThe anus is the focus of pleasurable sensations in the baby’s body, and toilet training is the most important activity. |

Autonomy vs. Shame and DoubtChildren either become self- |

|

3- |

Phallic StageThe phallus, or penis, is the most important body part, and pleasure is derived from genital stimulation. Boys are proud of their penises; girls wonder why they don’t have them. | Initiative vs. GuiltChildren either try to undertake many adultlike activities or internalize the limits and prohibitions set by parents. They feel either adventurous or guilty. |

|

6- |

LatencyNot really a stage, latency is an interlude. Sexual needs are quiet; psychic energy flows into sports, schoolwork, and friendship. | Industry vs. InferiorityChildren busily practice and then master new skills or feel inferior, unable to do anything well. |

| Adolescence | Genital StageThe genitals are the focus of pleasurable sensations, and the young person seeks sexual stimulation and satisfaction in heterosexual relationships. | Identity vs. Role ConfusionAdolescents task themselves “Who am I?” They establish sexual, political, religious, and vocational identities or are confused about their roles. |

| Adulthood | Freud believed that the genital stage lasts throughout adulthood. He also said that the goal of a healthy life is “to love and to work.” |

Intimacy vs. IsolationYoung adults seek companionship and love or become isolated from others, fearing rejection.Generativity vs. StagnationMiddle- |

Freud maintained that sensual satisfaction (from stimulation of the mouth, anus, or penis) is linked to major developmental stages, needs and challenges. During the oral stage, for example, sucking provides not only nourishment but also erotic joy and attachment to the mother. Kissing in adulthood is a vestige of the oral stage. Next, during the anal stage, pleasures arise from self-

40

One of Freud’s most influential ideas was that each stage includes its own potential conflicts. Conflict occurs, for instance, when mothers try to wean their babies (oral stage) or when parents try to control the sexual interests of adolescents (genital stage). According to Freud, how people experience and resolve these conflicts determines personality lifelong because “the early stages provide the foundation for adult behavior” (Salkind, 2004, p. 125).

Freud did not believe that new stages occurred after puberty; rather, he believed that adult personalities and habits were influenced by earlier stages. Unconscious conflicts rooted in early life may be evident in adult behavior—

For all of us, psychoanalytic theory contends, that childhood fantasies and memories remain powerful lifelong, particularly as they affect the sex drive (which Freud called the libido). If you have ever wondered why lovers call each other “baby” or why many people refer to their spouse as their “old lady” or “sugar daddy,” then Freud’s theory provides an explanation: The parent–

41

Erikson’s Ideas

Many of Freud’s followers became famous theorists themselves. They acknowledged the importance of the unconscious and of early childhood experience, but each of them expanded and modified Freud’s ideas. One of them, Erik Erikson (1902–

Erikson’s mother, pregnant with him, left her native Denmark alone by train to Germany, where she later married Erikson’s pediatrician. After a traditional German education, in emerging adulthood Erikson left Germany to wander for years in Italy, as did many artistic young adults at that time. When he decided to settle down, he became an art teacher for the children of Freud’s patients, who had traveled to Vienna for psychoanalysis. He met and married a Canadian, fleeing to the United States just before World War II. His temperament, his travel, and his studies of Harvard students, Boston children at play, and child-

Erikson described eight developmental stages, each characterized by a particular challenge, or developmental crisis (summarized in Table 2.1). Although Erikson named two polarities at each crisis, he recognized a wide range of outcomes between those opposites. For most people, development at each stage leads to neither extreme but to something in between.

In initiative versus guilt, for example, 3-

As you can see from Table 2.1, Erikson’s first five stages are closely related to Freud’s stages. Erikson, like Freud, believed that problems of adult life echo unresolved childhood conflicts. For example, an adult who has difficulty establishing a secure, mutual relationship with a life partner may never have resolved the first crisis of early infancy, trust versus mistrust. Or perhaps in late adulthood, one older person may be outspoken while another avoids saying anything, because each resolved the initiative-

- Erikson’s stages emphasize family and culture, not sexual urges.

- Erikson recognizes adult development, with three stages after adolescence.

Especially for Teachers Your kindergartners are talkative and always moving. They almost never sit quietly and listen to you. What would Erik Erikson recommend?

Response for Teachers: Erikson would note that the behavior of 5-

42

Behaviorism: Conditioning and Social Learning

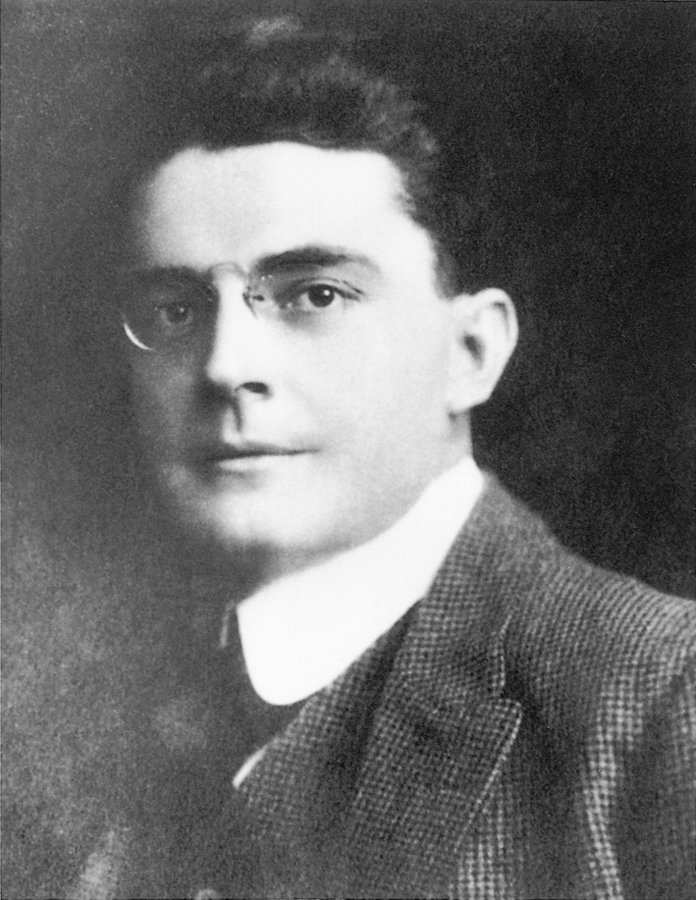

The second grand theory arose in direct opposition to the psychoanalytic notion of the unconscious. John B. Watson (1878–

Why don’t we make what we can observe the real field of psychology? Let us limit ourselves to things that can be observed, and formulate laws concerned only with those things…. We can observe behavior—

[Watson, 1924/1998, p. 6]

According to Watson, if psychologists focus on behavior, they will realize that everything can be learned. He wrote:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-

[Watson, 1924/1998, p. 82]

behaviorism A grand theory of human development that studies observable behavior. Behaviorism is also called learning theory because it describes the laws and processes by which behavior is learned.

Other psychologists, especially in the United States, agreed. They developed behaviorism to study actual behavior, objectively and scientifically. Behaviorism is also called learning theory because it describes how people learn—

conditioning According to behaviorism, the processes by which responses become linked to particular stimuli and learning takes place. The word conditioning is used to emphasize the importance of repeated practice, as when an athlete conditions his or her body to perform well by training for a long time.

Learning theorists believe that development occurs not in stages but in small increments: A person learns to talk, read, or anything else one tiny step at a time. Behaviorists study the laws of conditioning, the processes by which responses link to particular stimuli. In the first half of the twentieth century, behaviorists described only two types of conditioning: classical and operant.

Classical Conditioning

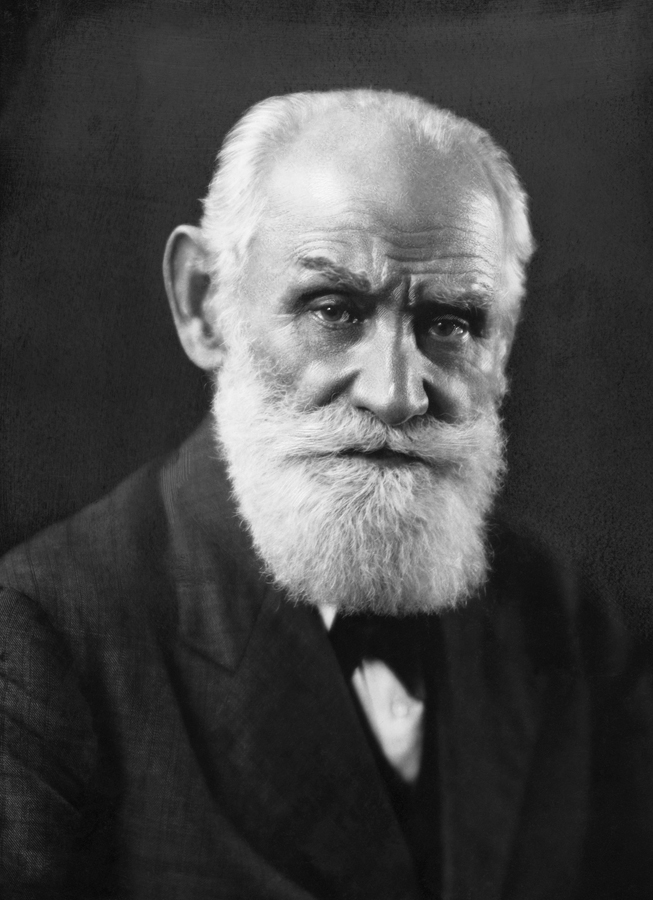

A century ago, Russian scientist Ivan Pavlov (1849–

classical conditioning The learning process in which a meaningful stimulus (such as the smell of food to a hungry animal) is connected with a neutral stimulus (such as the sound of a tone) that had no special meaning before conditioning. (Also called respondent conditioning.)

Pavlov began by sounding a tone just before presenting food. After a number of repetitions of the tone-

In classical conditioning, a person or animal learns to associate a neutral stimulus with a meaningful stimulus, gradually responding to the neutral stimulus in the same way as to the meaningful one. In Pavlov’s original experiment, the dog associated the tone (the neutral stimulus) with food (the meaningful stimulus) and eventually responded to the tone as if it were the food itself. The conditioned response to the tone (no longer neutral but now a conditioned stimulus) was evidence that learning had occurred.

43

Observation Quiz How is Pavlov similar to Freud in appearance, and how do both look different from the other theorists pictured?

Answer to Observation Quiz: Both are balding and have white beards. Note that none of the other theorists in this chapter have beards—

Behaviorists see dozens of examples of classical conditioning in life-

One specific example of classical conditioning is called the white coat syndrome, when past experiences with medical professionals have conditioned someone to feel anxious. For that reason, when someone dressed in white takes their blood pressure, it is higher than it would be under normal circumstances. White coat syndrome is apparent in about half of the United States population over age 80 (Bulpitt et al., 2013). Many nurses now wear colorful blouses and many doctors wear street clothes to prevent conditioned anxiety in patients.

Operant Conditioning

operant conditioning The learning process by which a particular action is followed by something desired (which makes the person or animal more likely to repeat the action) or by something unwanted (which makes the action less likely to be repeated). (Also called instrumental conditioning.)

The most influential North American proponent of behaviorism was B. F. Skinner (1904–

Pleasant consequences are sometimes called rewards, but behaviorists do not call them that because what some other people call “punishment” may actually be a pleasant consequence and vice versa. For example, parents think they punish their children by withholding dessert, by spanking them, by not letting them play, by speaking harshly to them, and so on. But a particular child might dislike the dessert, so being deprived of it is no punishment. Or a child might not mind a spanking, especially if that is the only time the child gets parental attention. Thus, an intended punishment becomes a reward.

Especially for Teachers Same problem as previously (talkative kindergartners), but what would a behaviorist recommend?

Response for Teachers: Behaviorists believe that anyone can learn anything. If your goal is quiet, attentive children, begin by reinforcing a moment’s quiet or a quiet child, and soon all the children will be trying to remain attentive for several minutes at a time.

Similarly, teachers sometimes send misbehaving children out of the classroom and principals suspend them from school. However, if a child hates the teacher, leaving class is rewarding. In fact, research on school discipline finds that some measures, including school suspension, increase later misbehavior (Osher et al., 2010). In order to stop misbehavior, it is more effective to encourage good behavior, to “catch them being good.” The true test is the effect a consequence has on the individual’s future actions, not whether it is intended to be a reward or a punishment. A child, or an adult, who repeats an offense may have been reinforced, not punished, for the first infraction.

44

reinforcement The process by which a behavior is followed by something desired, such as food for a hungry animal or a welcoming smile for a lonely person.

Consequences that increase the frequency or strength of a particular action are called reinforcers, in a process called reinforcement (Skinner, 1953). Almost all of our daily behavior, from saying “Good morning” to earning a paycheck, can be understood as the result of past reinforcement, according to behaviorism, although the laws are hard to pin down.

The problem is that research on conditioning has discovered that individuals vary in their responses, as already noted with spanking. In another example, a longitudinal study of children’s physical activity (playing sports, exercising, and so on) found that, for boys, the father’s praise was especially important. For girls, the father’s reinforcement helped, but the mother’s own physical activity was the more powerful influence (Cleland et al., 2011).

Social Learning

The importance of the father and mother in our last example provides another insight. At first, behaviorists thought all behavior arose from a chain of learned responses, the result of either the association between one stimulus and another (classical conditioning) or of past reinforcement (operant conditioning). Both of those processes—

social learning theory An extension of behaviorism that emphasizes the influence that other people have over a person’s behavior. Even without specific reinforcement, every individual learns many things through observation and imitation of other people.

modeling The central process of social learning, by which a person observes the actions of others and then copies them. (Modeling is also called observational learning.)

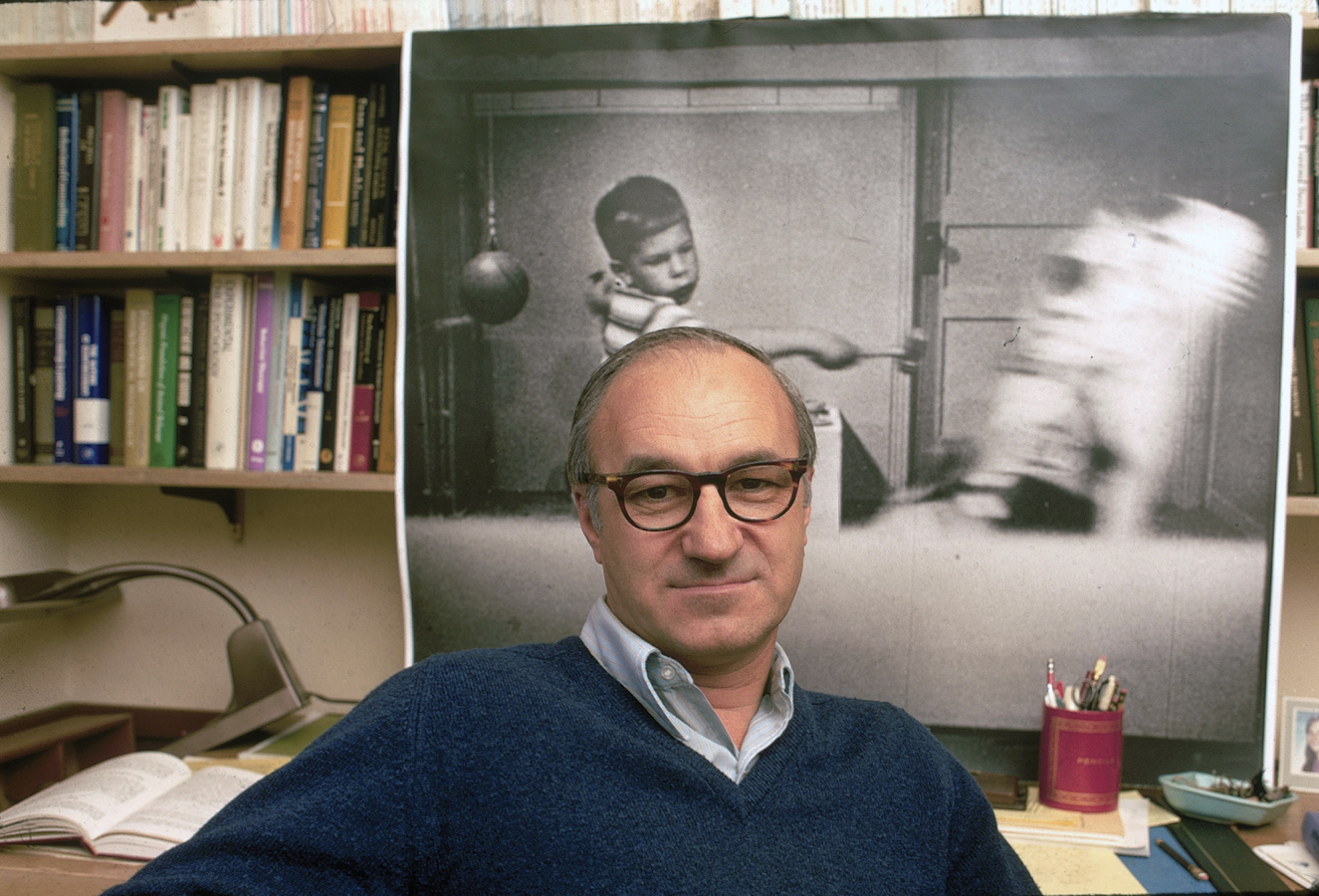

That social interplay is the foundation of social learning theory (see Table 2.2), which holds that humans sometimes learn without personal reinforcement. This learning often occurs through modeling, when people copy what they see others do (also called observational learning). Modeling is not simple imitation; not every role model is equal. Instead, people model only some actions, of some individuals, in some contexts.

| Type of Learning | Learning Process | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Conditioning | Learning occurs through association. | Neutral stimulus becomes conditioned response. |

| Operant Conditioning | Learning occurs through reinforcement and punishment. | Weak or rare responses becomes strong, frequent responses— |

| Social Learning | Learning occurs through modeling what others do. | Observed behaviors become copied behaviors. |

As an example of social learning, you may know adults who, as children, saw their parents hit each other. Some such adults abuse their own partners, while others scrupulously avoid marital conflict. These two responses seem opposite, but both are the result of social learning produced by childhood observation, with one observing the benefits of abuse, the other noting the suffering. Still other adults seem unaffected by their parents’ past fights: Differential susceptibility (explained in Chapter 1) may be the reason.

45

Generally, modeling is most likely when the observer is uncertain or inexperienced (which explains why modeling is especially powerful in childhood) and when the model is admired, powerful, nurturing, or similar to the observer (Bandura, 1986, 1997).

Social learning is common in adulthood as well. If your speech, hairstyle, or choice of shoes is similar to those of a celebrity, ask yourself why? Admiration? Similarity? Fads and fashions are most evident in adolescence and emerging adulthood because teenagers want to distinguish themselves from their parents, but they are uncertain as to how to dress or behave.

Cognitive Theory: Piaget and Information Processing

cognitive theory A grand theory of human development that focuses on changes in how people think over time. According to this theory, our thoughts shape our attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors.

Social scientists sometimes write about the “cognitive revolution,” which occurred in about 1980 when psychoanalytic and behaviorist research and therapy were overtaken by a focus on cognition. According to cognitive theory, thoughts and expectations profoundly affect attitudes, beliefs, values, assumptions, and actions.

This revolution was the result of increasing awareness of the power of cognition, a term that refers to thinking. Ideas, education, and language are considered part of cognition. Cognitive theory dominated psychology for decades, becoming a grand theory.

Piaget’s Stages of Development

The first major cognitive theorist was the Swiss scientist Jean Piaget (1896–

However, the children’s wrong answers caught his attention. How children think is much more revealing, Piaget concluded, than what they know.

AMI PARIKH/SHUTTERSTOCK

ZHANG BO/GETTY IMAGES

In the 1920s, most scientists believed that babies could not yet think. Then Piaget used scientific observation with his own three infants, finding them curious and thoughtful. Later he studied hundreds of schoolchildren. From this work Piaget formed the central thesis of cognitive theory: How children think changes with time and experience, and their thought processes affect their behavior. According to cognitive theory, to understand humans one must understand thinking.

46

Piaget maintained that cognitive development occurs in four age-

| Name of Period | Characteristics of the Period | Major Gains During the Period | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birth to 2 years | Sensorimotor | Infants use senses and motor abilities to understand the world. Learning is active, without reflection. | Infants learn that objects still exist when out of sight (object permanence) and begin to think through mental actions. |

|

2- |

Preoperational | Children think symbolically, with language, yet children are egocentric, perceiving from their own perspective. | The imagination flourishes, and language becomes a significant means of self- |

|

6- |

Concrete operational | Children understand and apply logic. Thinking is limited by direct experience. | By applying logic, children grasp concepts of conservation, number, classification, and many other scientific ideas. |

| 12 years through adulthood | Formal operational | Adolescents and adults use abstract and hypothetical concepts. They can use analysis, not only emotion. | Ethics, politics, and social and moral issues become fascinating as adolescents and adults use abstract, theoretical reasoning. |

cognitive equilibrium In cognitive theory, a state of mental balance in which people are not confused because they can use their existing thought processes to understand current experiences and ideas.

Piaget found that intellectual advancement occurs because humans at every age seek cognitive equilibrium—a state of mental balance. The easiest way to achieve this balance is to interpret new experiences through the lens of preexisting ideas. For example, infants grab new objects in the same way that they grasp familiar objects, children interpret their parents’ behavior by assuming that adults think in the same way that children do, and adults do the same when interpreting children.

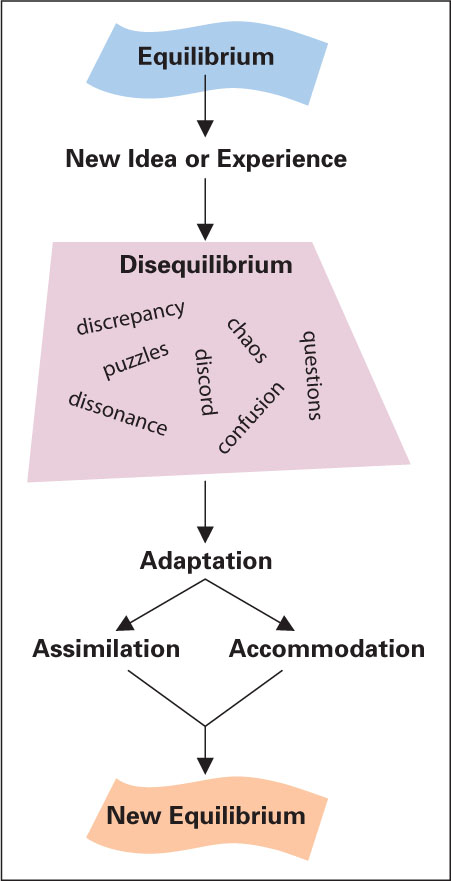

Achieving equilibrium is not always easy, however. Sometimes a new experience or question is jarring or incomprehensible. Then the individual experiences cognitive disequilibrium, an imbalance that creates confusion. As Figure 2.1 illustrates, disequilibrium can cause cognitive growth if people adapt their thinking. Piaget describes two types of cognitive adaptation:

- Assimilation: New experiences are reinterpreted to fit into, or assimilate old ideas.

assimilation The reinterpretation of new experiences to fit into old ideas.

- Accommodation: Old ideas are restructured to include, or accommodate, new experiences.

accommodation The restructuring of old ideas to include new experiences.

Accommodation is more difficult to achieve than assimilation, but it produces intellectual advancement. For example, if a friend’s questions reveal inconsistencies in your own opinions, or if your favorite chess strategy puts you in checkmate, or if your mother says something completely unexpected, disequilibrium occurs. In the last example, you might assimilate by deciding your mother didn’t mean what you heard. You might tell yourself that she was repeating something she had read or that you misheard her. However, intellectual growth would occur if, instead, you changed your view of your mother to accommodate a new, expanded understanding.

47

Ideally, when two people disagree, or when they surprise each other by what they say, adaptation is mutual. For example, when parents are startled by their children’s opinions, the parents may revise their concepts of their children and even of reality, accommodating to new perceptions. If an honest discussion occurs, the children, too, might accommodate. Cognitive growth is an active process, dependent on clashing concepts that require new thought.

Information Processing

Piaget is credited with discovering that people’s assumptions and perceptions affect their development, an idea now accepted by most social scientists. However, many think Piaget’s theories were limited. Neuroscience, cross-

As one admirer explains, Piaget’s “claims were too narrow and too broad” (Hopkins, 2011, p. 35). The narrowness comes from his focus on understanding the material world, ignoring the fact that people can be advanced in physics, biology, and math but not in other aspects of thought. The excessive broadness is reflected in his description of stages, ignoring the ongoing variability in thought. Contrary to Piaget’s ideas, “intelligence is now viewed more as a modular system than as a unified system of general intelligence” (Hopkins, 2011, p. 35).

information-

Here we introduce one newer version of cognitive theory, information-

Information processing is “a framework characterizing a large number of research programs” (Miller, 2011, p. 266). Instead of merely interpreting responses by infants and children, as Piaget did, this cognitive theory focuses on the processes of thought—

For information-

However, the basic tenet of cognitive theory is true for information processing and for Piaget: Ideas matter. For instance, an information-

48

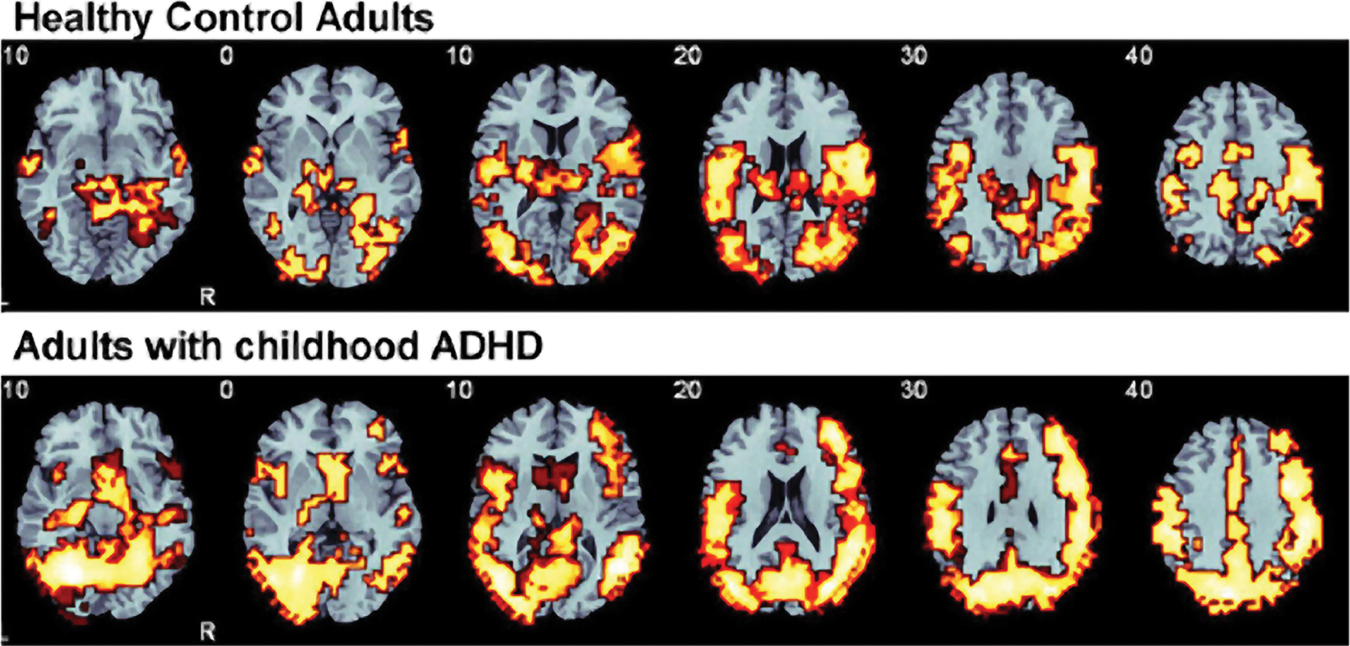

This approach to understanding cognition has many other applications. For example, it has long been recognized that children with ADHD (attention-

This means that children with ADHD may not know whether their father’s “Come here” is an angry command or a loving suggestion, or when a classmate is hostile or friendly. Information processing helps in remediation: If a specific brain function can be improved, children may learn more, obey more, and gain friends.

Comparing Grand Theories

The grand theories have endured because they were innovative, comprehensive, and surprising. Until these theories were developed, few imagined that childhood experiences or the unconscious exert such power (psychoanalytic) or that adult behavior arises from prior reinforcement (behaviorist) or that children have quite different ways of thinking—

These grand theories have also been soundly criticized, with many psychologists rejecting psychoanalytic theory as unscientific (Mills, 2004), behaviorism as demeaning of human potential (Chein, 1972/2008), and cognitive theory as disconnected from the social context that affects behavior. All three theories may emphasize past experiences and thoughts instead of future possibilities (Seligman et al., 2013). And, of course, they all reflect historical and cultural influences of their time (see Visualizing Development 2, p. 49).

The methods of these grand theories also differ.

- Freud and Erikson thought unconscious drives and early experiences formed the basis for later personality and behavior, so they listened to people’s dreams and memories, and incorporated themes from past myths and history.

- Behaviorists instead stressed actual experiences in each individual’s life, focusing on learning by association, by reinforcement, and by observation. For that reason they collected experimental data on animals of all kinds, believing that laws of behavior apply to all creatures, including humans.

- Cognitive theory held that to understand a person one must learn how that person thinks. Accordingly, Piaget gave children intellectual tasks and listened to their answers.

49

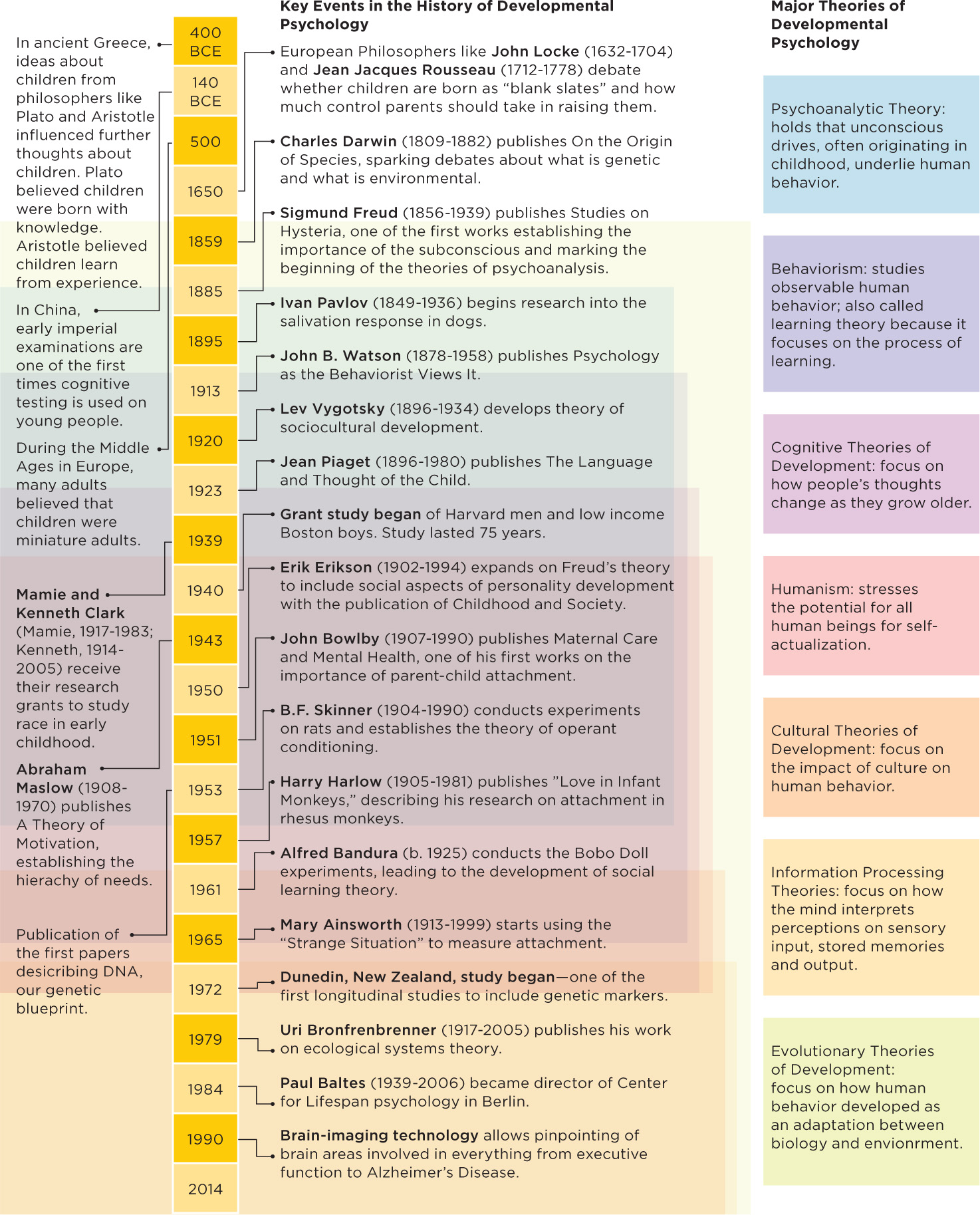

VISUALIZING DEVELOPMENT

Highlights from Developmental Psychology over the Centuries

50

Despite all their differences, like all good theories these three grand theories are provocative, each leading to newer theories (as shown here by Erikson, Bandura, and information processing), to hypotheses tested in thousands of experiments, and to countless applications. Here is one example.

OPPOSING PERSPECTIVES

Toilet Training—How and When?

Remember that theories are practical. For example, parents hear opposite advice about when to respond to an infant’s cry. Some experts tell them that ignoring the cry will affect the infant’s future happiness (psychoanalytic—

Meanwhile, cognitive theory seeks to understand the reason for the cry. Is it a reflexive wail of hurt and hunger, or is it an expression of social pain? According to this theory, when the meaning of an action is understood, people can respond effectively. Thus all three theories have led to advise for parents—

Another practical example is toilet training. In the nineteenth century, many parents believed that, to distinguish humans from lower animals, bodily functions should be controlled as soon as possible. Consequently, they began toilet training in the first months of life (Accardo, 2006). Then psychoanalytic theory pegged the first year as the oral stage (Freud) or the time when trust was crucial (Erikson), before the toddler’s anal stage (Freud) or autonomy needs(Erikson).

Consequently, applying psychoanalytic theory led to postponing toilet training to avoid serious personality problems later on. Soon this was part of many manuals on child rearing. For example, a leading pediatrician, Barry Brazelton, wrote a popular book for parents advising that toilet training should not begin until the child is cognitively, emotionally, and biologically ready—

As a society, we are far too concerned about pushing children to be toilet trained early. I don’t even like the phrase “toilet training.” It really should be toilet learning.

[Brazelton & Sparrow, 2006, p. 193]

By the middle of the twentieth century, many U.S. psychologists had rejected psychoanalytic theory and become behaviorists. Since they believed that learning depends primarily on conditioning, some suggested that toilet training occur whenever the parent wished, not at a particular age. In one application of behaviorism, children drank quantities of their favorite juice, sat on the potty with a parent nearby to keep them entertained, and then, when the inevitable occurred, the parent praised and rewarded them—

51

Rejecting both of these theories, some Western parents prefer to start potty training very early. One U.S. mother began training her baby just 33 days after birth. She noticed when her son was about to defecate, held him above the toilet, and had trained him by 6 months (Sun & Rugolotto, 2004). Such early training is criticized by all of the grand theories, although each theory has a particular perspective, as now explained.

Behaviorists would say that the mother was trained, not the son. She taught herself to be sensitive to his body; she was reinforced when she read his clues correctly. Psychoanalysts would wonder what made her such an anal person, with a need for cleanliness and order that did not consider the child’s needs. Cognitive theory would wonder what the mother was thinking, particularly if she had an odd fear of normal body functions.

What is best? Dueling theories and diverse parental practices have led the authors of an article for pediatricians to conclude that “despite families and physicians having addressed this issue for generations, there still is no consensus regarding the best method or even a standard definition of toilet training” (Howell et al., 2011, p. 262). One comparison study of toilet-

That conclusion arises from cognitive theory, which holds that each person’s assumptions and ideas determine their actions. Therefore, since North American parents are from many cultures with diverse assumptions, marked variation is evident in beliefs regarding toilet training. Contemporary child-

What values are embedded in each practice? Psychoanalytic theory focuses on later personality, behaviorism stresses conditioning of body impulses, and cognitive theory considers variation in the child’s intellectual capacity and in adult values. Even the idea that each child is different, making no one method best, is the outgrowth of a theory. There is no easy answer, but many parents are firm believers in one approach or another. That confirms the statement at the beginning of this chapter, that we all have theories, sometimes strongly held, whether we know it or not.

SUMMING UP

The three grand theories originated decades ago, each pioneered by thinkers who set forth psychological frameworks so comprehensive and creative that they deserve to be called “grand.” Each grand theory has a different focus: emotions (psychoanalytic theory), actions (behaviorism), and thoughts (cognitive theory).

Freud and Erikson thought unconscious drives and early experiences form later personality and behavior. Behaviorists stress experiences in the more recent past and focus on learning by association, by reinforcement, and by observation. Cognitive theory holds that to understand a person, one must learn how that person thinks, either in stages (Piaget) or in the organization and maturation of many components of the brain (information processing).