8.1 Body Changes

In early childhood as in infancy, the body and brain develop according to powerful epigenetic forces, biologically driven and socially guided, experience-

Growth Patterns

Compare a toddling, unsteady 1-

In fact, the average body mass index (BMI, the ratio of weight to height) is lower at ages 5 and 6 than at any other time of life. Gone are the infant’s protruding belly, round face, short limbs, and large head. The center of gravity moves from the breast to the belly, enabling cartwheels, somersaults, and many other motor skills. The joys of dancing, gymnastics, and pumping a swing become possible; changing proportions enable new achievements. [Lifespan Link: Body mass index is discussed in Chapter 11.]

216

Increases in weight and height are apparent as well. Over each year of early childhood, well-

- Weighs between 40 and 50 pounds (between 18 and 22 kilograms)

- Is at least 3½ feet tall (more than 100 centimeters)

- Looks lean, not chubby (ages 5 to 6 are lowest in body fat)

- Has adult-

like body proportions (legs constitute about half the total height)

When many ethnic groups live together in a nation with abundant food and adequate medical care, children of African descent tend to be tallest, followed by those of European descent, then Asians, and then Latinos. However, height differences are greater within ethnic groups than between groups, evidence again that ethnicity is not determined by genes.

Nutrition

Although they rarely starve, preschool children sometimes suffer from poor nutrition. The main reason for preschool malnourishment in developed nations is that too often young children’s small appetites are satiated with unhealthy foods, crowding out needed vitamins.

Adults often encourage children to eat, protecting them against famine that was common a century ago. Unfortunately, that encouragement is destructive when food is abundant. This is true in many nations: In Brazil 30 years ago, the most common nutritional problem was undernutrition; now it is overnutrition (Monteiro et al., 2004), with low-

A detailed study of 2-

One explanation for North American ethnic differences is that many low-

Overfed children often become overweight adults. An article in The Lancet (the leading medical journal in England) predicted that by 2020, 228 million adults worldwide will have diabetes (more in India than in any other nation) as a result of unhealthy eating habits acquired in childhood. This article suggests that measures to reduce childhood overeating in the United States have been inadequate and that “U.S. children could become the first generation in more than a century to have shorter life spans than their parents if current trends of excessive weight and obesity continue” (Devi 2008, p. 105).

Appetite decreases between ages 2 and 6 because young children need fewer calories per pound than they did as infants. This is especially true for the current generation since children get much less exercise than former generations did. They do not tend the farm animals, walk long distances to school, or even play outside for hours. However, instead of accepting this generational change, many of the older generations fret, threaten, and cajole children to overeat (“Eat all your dinner and you can have ice cream”). Pediatricians have found that most parents of infants, toddlers, and preschoolers believe that relatively thin children are less healthy than relatively heavy ones, a false belief that leads to overfeeding (Laraway et al., 2010).

217

Nutritional Deficiencies

Especially for Nutritionists A parent complains that she prepares a variety of vegetables and fruits, but her 4-

Response for Nutritionists: The nutritionally wise advice would be to offer only fruits, vegetables, and other nourishing, low-

Although most children in developed nations consume more than enough calories, they do not always obtain adequate iron, zinc, and calcium. For example, children now drink less milk than formerly, which means less calcium and weaker bones later on. Another problem is sugar. Many customs entice children to eat sweets—

Sweetened cereals and drinks (advertised as containing 100 percent of daily vitamins) are a poor substitute for a balanced, varied diet, partly because some nutrients have not yet been identified, much less listed on food labels. The lack of micronutrients is severe in poor nations, but vitamin pills and added supplements do not always help (Ramakrishnan et al., 2011).

Eating a wide variety of fresh foods may therefore be essential for optimal health. Compared with the average child, those preschoolers who eat more dark-

An added complication is that an estimated 3 to 8 percent of all young children are allergic to a specific food—

Some experts advocate total avoidance of the offending food—

Especially for Early-

Response for Early-

Oral Health

Too much sugar and too little fiber cause tooth decay, the most common disease of young children in developed nations. More than one-

Fortunately, “baby” teeth are replaced naturally at about ages 6 to 10. The schedule is primarily genetic, with girls averaging a few months ahead of boys. However, tooth care should not be postponed until the permanent teeth erupt. Severe tooth decay in early childhood harms those permanent teeth (which form below the first teeth) and can cause jaw malformation, chewing difficulties, and speech problems.

218

Teeth are affected by diet and illness, which means that the state of a young child’s teeth can alert adults to other health problems. The process works in reverse as well: infected teeth can affect the rest of the child’s body.

Most preschoolers visit the dentist if they have U.S.-born, middle-

If the parent was raised in a nation with inadequate dental care (sometimes visible in the number of toothless elders), they may not get dental care for their children. However, in many countries, ignorance is not the problem; access and income are. In the United States, free dentistry is not available to most poor parents, who “want to do better” for their children’s teeth than they did for their own (Lewis et al., 2010).

Hazards of “Just Right”

Many young children are compulsive about their daily routines, insisting that bedtime be preceded by tooth-

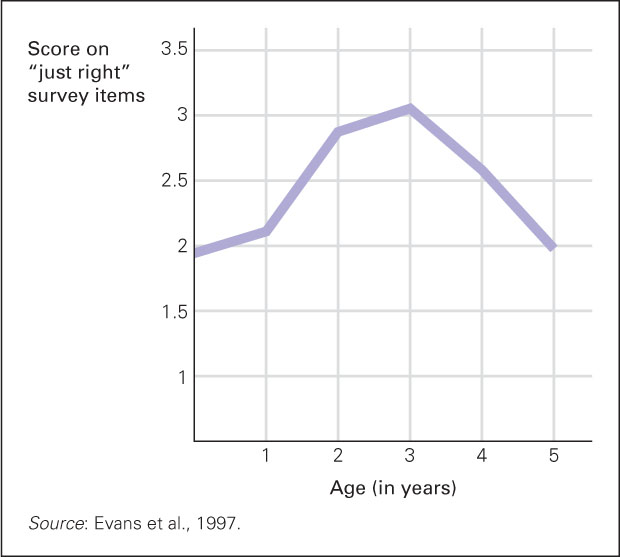

The early childhood wish for routines, known as the “just right” or “just so” phenomenon, might signify an obsessive-

Overeating can become a serious problem: Indulgence and patience for “just right” becomes destructive if the result is an overweight child. [Lifespan Link: Obesity is discussed in detail in Chapter 11, and Chapter 20.]

Pediatricians need to provide parents of 2-

SUMMING UP

Between ages 2 and 6, children grow taller and proportionately thinner, with variations depending on genes, nutrition, income, and ethnicity. Nutrition and oral health are serious concerns, as many children eat unhealthy foods, developing cavities and too much body fat. Young children usually have small appetites and picky eating habits. Unfortunately, many adults encourage overeating, not realizing that being overweight leads to life-

219