Analyzing Film Reviews: What to Look For

THE RHETORICAL SITUATION

Purpose Film reviewers write partly to inform readers about a particular movie; they discuss the film’s story and how it’s conveyed, and contextualize the film in terms of its director and actors, for example. However, the reviewer’s main purpose is to persuade readers about the movie’s overall quality and whether (from the reviewer’s perspective) it’s worth seeing. When a reviewer pans a film, some readers may decide not to spend money to see it in a theater; they might skip the movie altogether or wait for it to come out on DVD or through Netflix.

Reviewers make an argument about a film by analyzing certain aspects of it. For example, they may discuss the success with which the writer and director used narrative techniques such as flashbacks; they might consider the use of film techniques such as special effects, as well as cinematography and the use of close-up shots, for example. They may weigh in on the quality of the performances and comment on the overall cohesion of the work.

Audience Film reviewers write for popular audiences: general readers who get their entertainment news on TV, in local papers, and online at news and other sites. They may visit film-focused sites such as Rotten Tomatoes and the Internet Movie Database. Film reviewers know that their readers want (1) to decide whether to see a particular movie or (2) to get a reviewer’s perspective on a film they’ve already seen. For example, Liz often likes to read reviews after seeing a film so she can process her thoughts about it. Reviewers’ work might also be read by movie insiders, including directors and actors who want to know how their work is being received. Reviewers may keep this audience in mind as well when they critique a film.

Rhetorical appeals Film reviewers persuade readers by appealing to their sense of ethos, pathos, and logos. Reviewers need to develop their ethos as experts so readers will trust their judgment about a film. For example, in his review of the film Bridesmaids, Roger Ebert writes:

Three of my good female friends, who I could usually find overcoming hangovers at their Saturday morning “Recovery Drunches” at Oxford’s Pub, once made pinpricks in their thumbs and performed a ceremony becoming blood sisters. They were the only people I have actually known who could inspire a Judd Apatow buddy movie, and all three could do what not all women do well, and that is perfectly tell a dirty joke.

Maybe I liked Bridesmaids in their honor.

By mentioning that he knows women who “could inspire a Judd Apatow buddy movie,” Ebert builds his ethos. He establishes that he’s qualified to speak about the realism of the movie and the experience of women like his friends, women such as those the Bridesmaids characters were modeled on.

Film reviewers also tap into emotion as they seek to convince readers to agree with their critiques of specific movies. For example, reviewer David Edelstein appeals to pathos when, in his assessment of the final Harry Potter movie, he writes:

Seeing Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint, and Emma Watson together for presumably the last time brought a tear to my eye.

Think of something—films, restaurants, or products and services—that you regularly read reviews of. Have you ever doubted a reviewer’s credibility? Why?

The most persuasive film reviewer will also rely on logos, systematically building a case with evidence from the movie to support his or her main argument. For example, in a review of the film Cowboys & Aliens, Tom Long makes the claim in his title that the film is “big dumb summer fun.” He then gives specific examples to back this up. He discusses the film’s special effects, which constitute the “big” part of the argument, and also the silliness of the film, which constitutes the “fun” part of the argument. He writes:

[L]aser beams are blowing buildings up and metallic lassos are coming down from assorted flying machines and scooping people up.

Modes & media Film reviewers publish their work in written form (as discussed above), on paper and digitally online. They present their reviews as part of TV broadcasts, such as the reviews shown on E! Entertainment, as part of radio broadcasts, such as the audio reviews aired by National Public Radio, and on the Internet at ComingSoon.net, for example.

THE GENRE’S CONVENTIONS

Elements of the genre Film reviewers do the following:

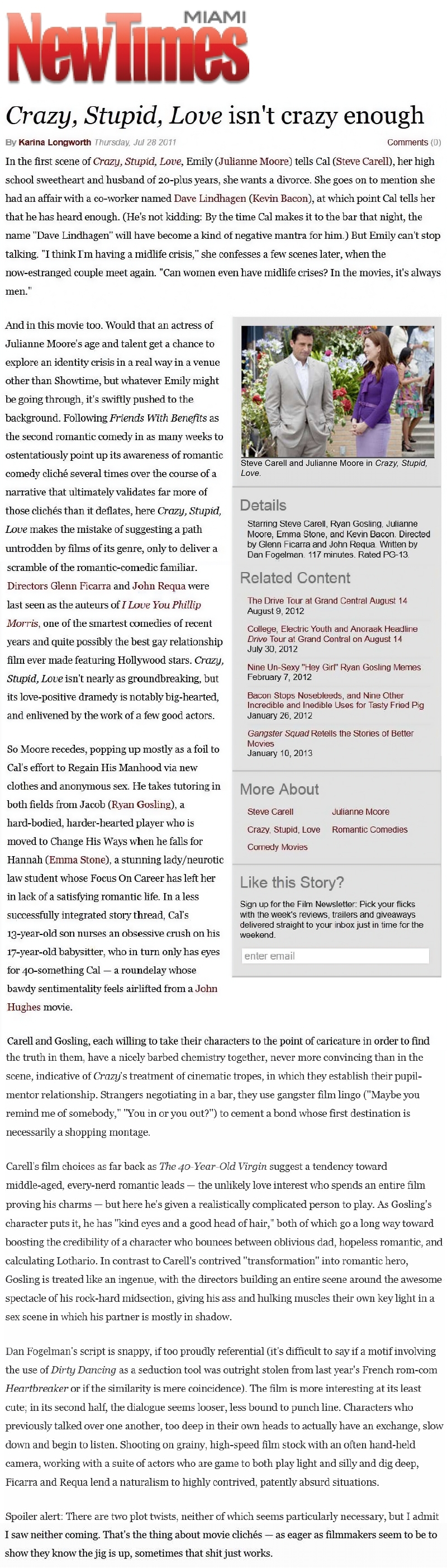

Create titles that identify the film and hint at their critique. For example, reviewer Karina Longworth titled her review of Crazy, Stupid, Love as follows: “Crazy, Stupid, Love Isn’t Crazy Enough.”

Write juicy lead paragraphs. Film reviewers want to grab readers’ attention right away, which is why their opening paragraphs tend to be provocative. A writer might begin by naming the film, identifying its genre, hinting at her evaluation and the argument she will present, and provide a hook to keep you reading. For example, Manohla Dargis writes in paragraph 1 of her review of Elizabeth: The Golden Age.

A kitsch extravaganza aquiver with trembling bosoms, booming guns and wild energy, Elizabeth: The Golden Age tells, if more often shouts, the story of the bastard monarch who ruled England with an iron grip and two tightly closed legs.

Discuss the film’s genre. As noted above, reviewers usually say what type of film they’re writing about, whether it’s an action, horror, or science fiction movie, or a comedy or drama. For example, in her review of Crazy, Stupid, Love, Karina Longworth comments on the film’s genre by pointing out its “romantic comedy clichés.”

Summarize the film’s narrative. Reviewers provide a brief outline of the film’s plot, characters, and setting, but they do not give away specific details such as endings and plot twists. (Doing so is called “spoiling” and it is frowned upon.)

Evaluate the filmmakers and actors. Reviewers name the key contributors to the film and mention a few of their other works in order to provide context. They also critique the success of each participant, for example, rating the writer’s and director’s editorial choices and the performances of the lead actors, while drawing on examples from specific moments from the movie to support the analysis.

Make a clear argument, critiquing the film overall. Reviewers make arguments about the overall success (or failure) of filmmakers—to achieve their purpose and reach their audience through specific films—in several ways. For example, a reviewer might begin by assigning a film they deem successful with four out of five stars, then build this case throughout the body of the review. Longworth, for example, states her main argument:

Crazy, Stupid, Love isn’t nearly as groundbreaking [as I Love You Phillip Morris], but its love-positive dramedy is notably big-hearted, and enlivened by the work of a few good actors.

She then praises the performances of the film’s stars, Julianne Moore, Steve Carell, Ryan Gosling, and Emma Stone, while opining that Moore deserved more screen time. So while her overall critique is that the film is not worth seeing, Longworth does point out some of the positives.

When a reviewer gives a film a thumbs-down, readers expect the writer to build an argument about how the film fails to entertain—in terms of the plot’s weaknesses or the actors’ poor performances, for example. Similarly, when a reviewer loves a film and recommends it, readers expect the writer to offer insights on how and why the film succeeds—in terms of the writing, filmmaking, directing, drama, excitement, acting, and special effects, for example.

Style Film reviewers do the following:

Use specific writing techniques, such as quoting from the film. Reviewers often quote from memorable or crucial-to-the-plot dialogue from the film in order to discuss the plot and characters in the work. They also quote from the dialogue to support their specific arguments and opinions about the movie.

Incorporate specific details. Reviewers persuade their readers that their generalizations about a film are legitimate by illustrating their points with specific details. Notice how Karina Longworth begins with a fairly general comment, then describes the details of a particular scene:

Carell and Gosling, each willing to take their characters to the point of caricature in order to find the truth in them, have a nicely barbed chemistry together, never more convincing than in the scene, indicative of Crazy’s treatment of cinematic tropes, in which they establish their pupil-mentor relationship. Strangers negotiating in a bar, they use gangster-film lingo (“Maybe you remind me of somebody.” “You in or you out?”) to cement a bond whose first destination is necessarily a shopping montage.

Use voice, tone, and word choice to convey ethos. To be persuasive, reviewers need to come across as knowledgeable film buffs. For example, Karina Longworth establishes that she’s knowledgeable about romantic comedies when she compares the one she’s reviewing (Crazy, Stupid, Love) to another film of the same genre (I Love You Phillip Morris). She also writes as an authority on performance, as evidenced in the excerpt from her review, above, about the chemistry between actors Carell and Gosling.

Design Film reviews:

Are formatted like news articles and editorials. Like other journalistic works that appear in print and online, a film review includes a headline, a title, and a byline identifying the reviewer (often with a photograph). Reviews are formatted in columns if printed or in single-spaced paragraphs if digital, and include masthead information, such as the name of the newspaper or Web site and the date.

Present a star rating system. Most reviewers work with a system in which they can assign up to five stars (or other symbols) to rate the success of a film. The star rating is often provided at the top or bottom of the review.

Include production credits. In some cases, reviewers include a list of the film’s credits, usually at the end of the review.

Feature a still photo from the film (or video if online). Many reviews include an image from a crucial moment in the film. For example, Longworth includes a photo of Carell and Moore.

Sources Film reviewers, like other journalists, do not include a Works Cited list or references list; they simply name their sources within their reviews as they refer to them. For example, many reviewers refer to other films to provide context for the one they’re writing about and to establish their own credibility as experts, as Karina Longworth does when she compares Crazy, Stupid, Love to another romantic comedy, I Love You Phillip Morris.