1.1 Today’s Psychological Science

Tens of thousands of people, worldwide, are engaged in the science of psychology. Six have described what they do for a living, to introduce you to their field. Let’s meet them.

Six Contemporary Psychologists

Preview Question

Question

What are some examples of the diversity characterizing the field of psychology?

What are some examples of the diversity characterizing the field of psychology?

What image comes to mind when you think of a psychologist?

If you dropped in on our six psychologists at work, here is what you would find.

PAULINE MAKI

If you walk into my research laboratory, you might see me giving someone this instruction:

After I say a word, come up with as many words as you can that rhyme with it. You’ll have one minute. Ready? The word is “name.” Go.

Why would a psychologist ask anybody to do this? The task measures mental performance. Researchers in psychology explore factors that affect how well people perform on tasks. There are many. Some are expected: how tired you are, how much effort you put into the task. But others are surprising. It turns out that, on average, women produce more words on this task than men do and that their performance can depend on the level, in their bodies, of the body chemical estrogen. Estrogen, which plays an important role in pregnancy, also affects mental abilities. Our research linking estrogen levels to thinking shows a tight connection between biology and the mind.

5

Body–

So that’s my job. I’m a scientist who studies how body chemistry affects the mind. We hope to better understand how the body’s inner chemistry, as well as the medications people take, impact mental abilities.

ED CUTRELL

When you envision a psychologist, you probably don’t imagine somebody who spends one week talking to farmers in rural India about composting, another talking with urban sex workers in Bangalore about how they use mobile phones, and another working with software engineers to design technologies. But that’s not unusual for me. I’m a psychologist at Microsoft Research India.

I try to understand how computing systems can improve life in developing communities. Although there are nearly 5 billion mobile phones worldwide, technology’s benefits remain out of reach for many. Some countries struggle to provide electricity and connectivity to all citizens, and some businesses and families can’t afford hardware. But finances aren’t the whole story. Limited education and literacy; political, gender, or religious prohibitions on technology use; and differences in cognitive models—

Our group has designed systems to help farmers share sustainable farming techniques; to help children share PCs in low-

LYNNE OWENS MOCK

When I tell people I’m a psychologist, they assume I have a leather couch where people lie down and tell me their troubles. However, I spend most of my time in communities in Chicago. I direct the research division of a community mental health center. In this job, I have a wide range of duties:

When community service organizations run programs, somebody has to figure out if they work. I do this. For example, I recently evaluated a voter registration rally and a program to develop leadership skills in young women. My psychological training helps me to learn what community leaders think, and to analyze and report scientific evidence that shows whether programs are working.

6

I coordinate a committee to monitor research ethics, in other words, whether it’s acceptable to conduct research in a certain way. This activity is common for psychologists; all our research follows ethical principles that protect people’s rights.

I run a support group for grandparents raising grandchildren. We discuss challenges such as substance abuse and raising boys to manhood. My psychology training taught me how to listen carefully and ask questions to help the group discuss experiences that are personal and sometimes painful. It also helps me update grandparents’ knowledge of child development, based on current research.

On top of this, I teach university courses, including African American Psychology. Real-

GLORIA BALAGUE

I am watching the team at practice; tomorrow I will be watching the game. I am working; I am the team’s sport psychologist.

I study psychological factors that affect athletic performance, for example:

Working together as a group. Even in individual sports (e.g., swimming), athletes train in groups. Interactions among team members can affect everybody’s performance.

Decision making: Athletes have to focus attention on key information, make quick decisions, and refocus quickly after a mistake or distraction.

Confidence: Athletes have to maintain confidence, even after a loss.

Controlling emotion: Athletes sometimes “choke,” losing control of their emotions and performing below their abilities. Controlling emotion is a skill people can learn.

When working with athletes, I draw on my training in clinical psychology. As in clinical work, sports psychologists teach people various skills to cope with difficulties. If someone—

The bottom line is that psychological skills, just like physical ones, are trainable. Everyone can improve mentally if they work at it. I guess I could be called a “head” coach.

7

ROBERT CALIN-JAGEMAN

When I tell somebody that I’m a psychologist, they’ll often ask what type of people I work with. Then I have to explain that I don’t work with people; I study Aplysia californica, a large sea slug that lives in the ocean. Usually, this is confusing enough to bring the conversation to a screeching halt. So I’ll introduce my work this way.

I am interested in how memories are formed. We constantly encounter information, some of which we remember permanently. I try to understand how the brain, a biological organ, can store and access memories.

What does this have to do with sea slugs? They provide an amazing opportunity to see how the brain stores memories. Like all animals, Aplysia form memories. But unlike most, they do it with an extremely simple nervous system: only 20,000 brain cells (by comparison, a honeybee has 1 million and humans have 100 billion). With so few cells, we can trace the cell-

Although sea slugs are a somewhat unusual topic of study, my day is typical for a research psychologist and college professor. In the morning, I check in with students in my lab, make sure the Aplysia are fed and comfortable, and then I’m off to teach classes. In the afternoon, it’s back to the lab. In the evening, I try to digest the day’s research results.

LEE L. MADDEN

Dropping by my office, you may see me talking with one person, or two, or even five. Depending on the patient(s) in the room and the topic discussed, there may be tears, laughter, hollering, or even silence. It’s what you don’t see that makes me a clinical psychologist.

Inside my head I am schema building. I am creating a knowledge base about the patient, testing my hypotheses, then crafting interventions to figure out exactly where the individual is stuck and how to help.

Psychology researchers, like those described earlier, garner scientific information that I need to assess the combination of psychological factors existing in each of my patients. The scientific findings help me to teach a patient lessons that are necessary for better self-

Building an understanding of patients and interventions for them—

8

The Diversity of Psychology

Our six psychologists provide your first look at today’s field of psychology. What did you observe? One can’t help but notice how much their jobs differ from one another. They work in laboratories, communities, athletic fields, and information-

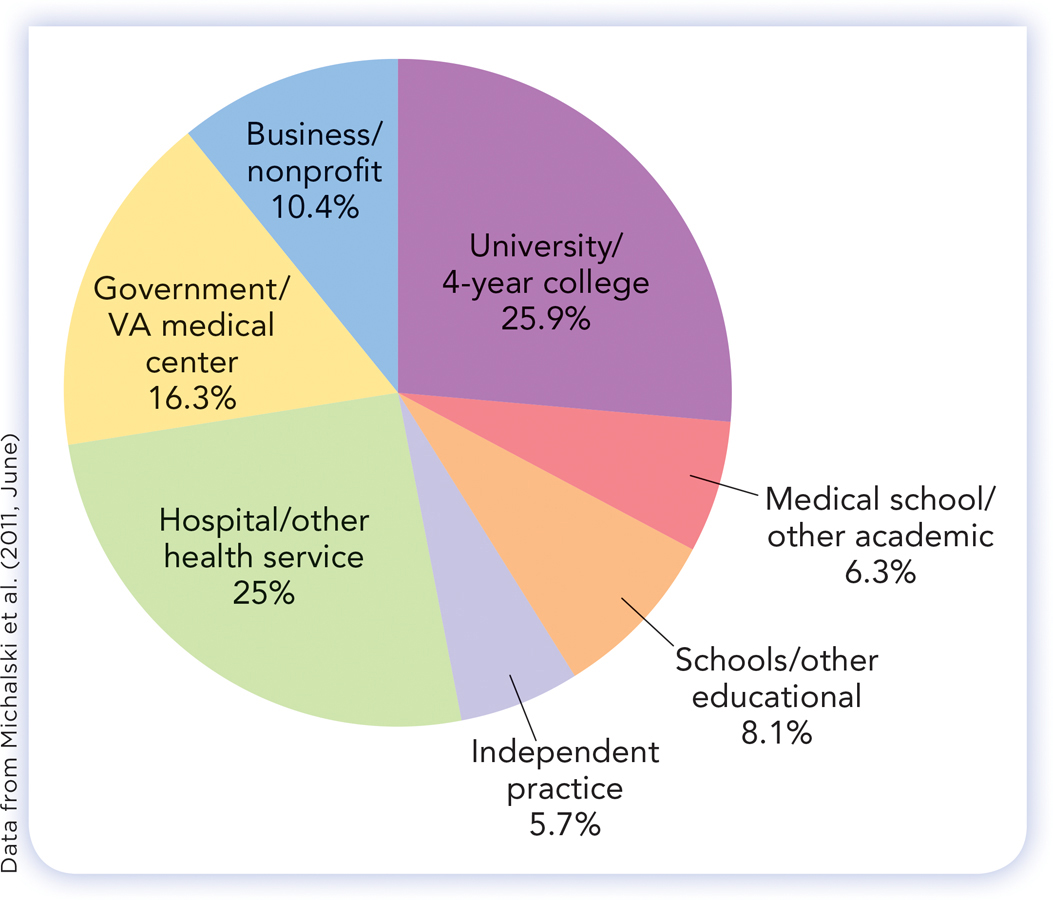

Additional biographies would reveal more diversity. Psychologists work in hospitals, schools, businesses, and governments (Figure 1.1). They study people ranging in age from fetuses (to discover the earliest age of consciousness, Chapter 9) to older adults (to understand the wisdom of old age, Chapter 14). They explore the inner mental life of individuals (e.g., when conducting therapy, Chapters 15 and 16), interactions among hundreds or thousands of individuals (in social psychology, Chapter 12), and “virtual” interactions among millions (in research conducted on social networking sites, Chapter 2). Some focus on the person as a whole, others on specific aspects of mental life, and yet others on biological mechanisms within the brain.

There is, then, no one type of job that encompasses “being a psychologist.” Psychologists bring a wide range of skills to a wide range of challenges.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 1

Py2wR0MfN4Ceg0tGJTeRiPtUvZVvzrpZb9V4Ty/h4pYiljhYJYOXfZASUqfOIc05t6cL3traYe/DDivGjSgoW493ZXURnj+Dc8rNFR4kuUQFLpcFwLDP1NaKROspnHPzlDU81OfXEM4+TT9SZnrQ0rJ02N8fZtTSvDEXw54KG3MbgBuU9doIFHBFK/65BeVp7sCX8lL49l1GpDCxEsYG6fQom8uku7nZ+jra7dlyz/fsMiC80cavXv96gNoL/exNAAhQ6bEicLmajWe6DIwf70eWTfTESjTGE6FS0KXuEHGGTDCmvhdDA8HXqQvnckl2SNaTTDtQKrQ=The Unity of Psychology

Preview Question

What’s so bad about intuition?

What’s so bad about intuition?

What’s a good alternative to intuition?

What’s a good alternative to intuition?

All this diversity raises a question. What common threads tie together psychologists’ activities? Sure, their work is diverse. But does it have anything in common?

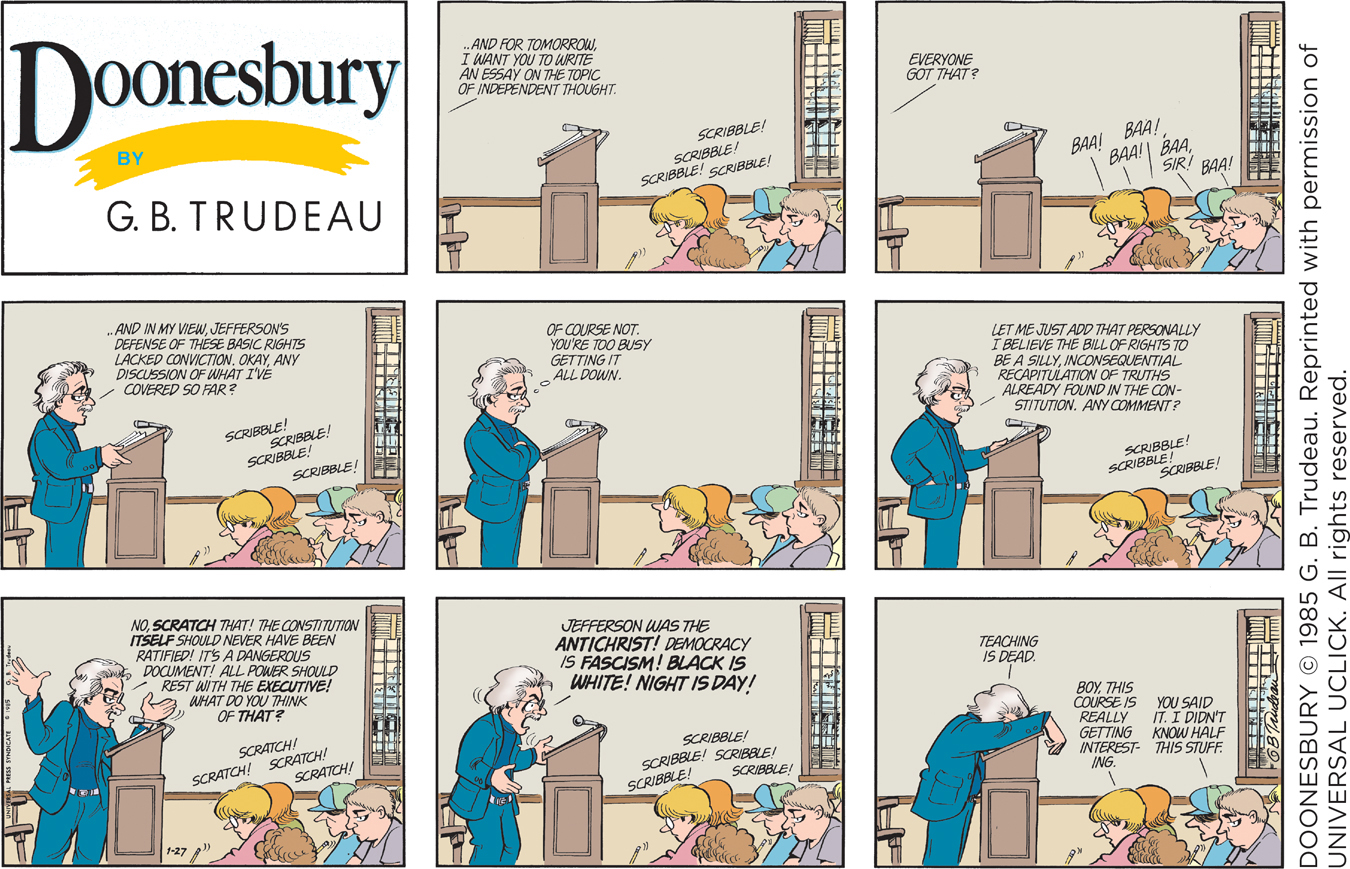

A key common thread is a commitment to the methods of science. This commitment helps to unify psychology and also to distinguish it from other fields. Novelists, journalists, poets, playwrights, and philosophers provide valuable ideas about human nature, just as psychologists do. But psychologists—

Other sciences—

In a moment, we will say more about scientific methods. But first, let’s look at intuition. The limits of intuition motivate psychologists to employ the methods of science.

What image comes to mind when you think of a scientist?

INTUITION AND ITS LIMITS. In psychology, are scientific methods really needed? The question arises due to the unique role of intuition—

9

When you take your first class in biology, chemistry, or physics, you have few intuitions about how things work. How do elements combine into chemical compounds? How do subatomic particles interact? Before taking the class, you haven’t the foggiest idea; you have no intuitions. But in psychology, you have many intuitions before class begins. Suppose that, on the first day of psychology class, your instructor asks, “What are the main ways that people’s personalities differ?” You probably have lots of intuitions about the answer. Your intuitions seem correct to you. And, in many cases, they might actually be correct (see Oltmanns & Turkheimer, 2009).

Your good intuitions could prompt you to ask, “In psychology, do we even need scientific research?” Maybe the field’s questions are “no brainers”: trivially easy to answer through intuition alone. If this is what you’re thinking, consider the psychological intuitions quoted in the right margin, expressed by various wise individuals.

Well, which is it? Does power corrupt or not? Are people evil or good? Do people want a just ruler or freedom? One thing’s for sure: We’re not going to find out by relying on intuitions. Intuitions are all over the map.

How many of the arguments you’ve experienced happened because you and someone else had different intuitions about the same question?

SCIENTIFIC METHODS. Psychology cannot live on intuition alone. It needs methods that are so convincing that everybody, no matter what their original intuitions, will recognize the value of the information they provide.

Fortunately, these methods already exist. They have been known for centuries as scientific methods.

The term scientific methods refers to a broad array of procedures through which scientists obtain information about the world. Scientific methods involve three key steps:

Collect evidence. Scientists do not just sit back and think about what the world might be like. They go out into the world and observe it. These observations provide the evidence on which they base their conclusions.

Record observations systematically. Scientists keep careful, precise accounts of what they observe, and summarize observations systematically (e.g., in tables and graphs). This gives them accurate records that can be communicated easily to other scientists.

Record how observations were made. Scientists don’t merely tell you what they observed. They also record exactly how they observed it: the equipment they used and steps they took to obtain the evidence. These records enable other scientists to engage in replication, that is, to repeat the procedures in order to verify the original results.

Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.

—Lord Acton (British historian and political theorist)

It is said that power corrupts, but actually it’s more true that power attracts the corruptible.

—David Brin (Author)

In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart.

—Anne Frank (Diarist and Holocaust victim)

All that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.

—Edmund Burke (Political theorist and philosopher)

God has planted in every human heart the desire to live in freedom.

—George W. Bush (U.S. president)

Few men desire liberty: The majority are satisfied with a just master.

—Sallust (Roman historian and politician)

When psychologists take these three steps to obtain information, they usually try to get a lot of information. Here’s an example involving the question “Are women more talkative than men?” In everyday life, you might answer based on a small amount of information from personal experience: “Yeah, sure they are. My friend Mark is really quiet, but Charlene is always talking up a storm.” Psychologists, by comparison, obtain a vast amount of information that goes far beyond personal experience. Two psychologists answered this question by analyzing results from 63 prior studies of talkativeness conducted between the years 1968 and 2004 (Leaper & Ayres, 2007). In each of the prior studies, researchers used the three steps above (collect evidence, record observations, and record how observations were made) to observe many men and women. Altogether, in the 63 studies combined, 4,385 people were observed. That’s a lot of information! It yielded a surprise: on average, men were slightly more talkative than women.

10

In addition to scientific observations, there is room in science for intuition. Scientists may rely on intuitions when first formulating their ideas (as you saw in the case of Claude Steele, in this chapter’s opening story). But to evaluate their ideas, they rely on evidence gathered through scientific methods.

TRY THIS!

In Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain, you not only will learn about the results of psychologists’ research, you will also get to experience their research methods firsthand, thanks to a feature called Try This! Get on the Internet and enter the Web address www.pmbpsychology.com to find Try This! research experiences for each chapter of the book.

Do the exercise for Chapter 1 now; it’s a test of your memory ability. We will discuss the results of this test later in the chapter.

And, speaking of memory, don’t forget to come back to read the rest of this chapter once you’re done.

Scientific methods are used throughout psychology—

Chapter 2 reviews scientific methods that psychologists use to answer questions. Here, let’s examine the questions themselves.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 2

Though relying on VupXV5vPAh+JKb7cfvxqrMCD0fKBrbNv may be useful when we first formulate ideas, psychologists evaluate those ideas using hiLd6zlEg4V1bvparx0U8Q== methods.

Question 3

r+k4CPt5BhwzW9TTCZZrNWbLGPWYOoBgnPblaeG7d78+ddvVz8byCWSCTDpfJK4oQsBuiFVpDY9P3PpD0GID2IW1LzK681bDvkqOCZ3R1SCVIDHyQiW9EjRx1pmXFeRzk/8zu+/ANB6+5aSVSFAshmfsVGb3IgjsXZm4X1cd+9fwwb65WwiBoj3t8nBxlea3Scientific and Nonscientific Questions About Human Behavior

Preview Question

Question

What makes a question “scientific”?

What makes a question “scientific”?

Psychologists use scientific methods to answer questions—

Scientific questions are ones that can be answered by gathering evidence through the scientific methods we just described. If a question is a scientific one, then evidence is required to answer the question convincingly. In other words, scientific questions are empirical; an empirical question is one that can be answered by making observations of the world that provide evidence.

11

Let’s experience scientific questions through an exercise. For each of the following questions about human behavior, ask yourself whether it is a scientific question (based on the definition above):

1A. Is it okay to break into a drug store and steal medicine if you’re extremely ill, desperately need the medicine, and can’t afford it?

1B. Do men and women differ in the degree to which they think it is okay to break into a drug store and steal medicine to help a person who is extremely ill, needs it, and can’t afford it?

2A. Are there really angels and, if so, how many are there?

2B. Why do so many people believe that there really are angels, when angels cannot be seen?

3A. Are all bachelors unmarried?

3B. Are married people happier or less happy than people who are single?

You surely noticed that the “A” and “B” questions differed. For the B questions, you could imagine evidence that would answer the question definitively. Sometimes getting the evidence would be easy; for example, you could ask men and women what they think about the drug store question (1B). Sometimes it would be difficult; it might be hard to answer 2B thoroughly (see, e.g., Boyer, 2001). Nonetheless, for all the B questions, you could gather evidence that would answer the question, and without evidence you cannot answer it convincingly. The questions are scientific.

The A questions are not like this; they cannot be answered by gathering evidence. They represent three other types of questions: normative questions, questions of faith, and questions of logic.

Normative questions ask how a person should act. (A norm is a rule or standard of excellence representing desirable or socially acceptable behavior.) If you ask yourself, “Should I lie to the guy I’m dating about why I want to break up, since it will be easier than telling the truth?” you’re asking a normative question. “Thou shalt not kill” answers a normative question (“Is killing acceptable?”). Normative questions are not answered by gathering evidence, but by appealing to accepted rules of conduct. No scientific evidence is even relevant to a norm such as “Thou shalt not kill.”

Questions of faith. Question 2A might sound like a scientific question, but it’s not. It is a question of faith, that is, one which rests on religious beliefs that cannot be proven through scientific facts. Religious beliefs address the supernatural world—

a realm beyond the world of nature studied by the sciences. Questions of logic. Like 2A, 3A also might look like a scientific question. Maybe you could gather evidence by asking a number of men two questions—

“Are you a bachelor?” and “Are you married?”—and determining whether answers to the questions go together. But don’t do that. Question 2A can be answered based solely on logic, that is, rules for drawing conclusions from statements. Because bachelor means “a man who is not married,” you do not need scientific evidence to answer Question 3B.

What are some things you believe, even if no scientific evidence exists to support your belief?

Now that you know what scientific questions are, it is important to recognize that they are not all the same; scientists ask different types of questions. When they are just starting to acquire knowledge, their scientific questions tend to be very general; they ask, in essence, “What is the world like?” For example, in Chapter 14 you will learn about a psychologist (Jean Piaget) who began his studies of children by giving them problems they had never seen before and asking, “Can they solve them? If so, how?” Later, scientists’ questions usually become more specific; they ask exactly how one factor influences another. You saw this in our opening story, where a psychologist predicted that a specific social factor (stereotypes) would have a specific effect on school performance (lower test scores). Chapter 2 presents the research methods psychologists use to answer different types of scientific questions.

12

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 4

“Is our God a loving god?” is an example of a question of uiJwm4ZFsWM7AUyn, whereas “Is it okay to watch pirated movies?” is an example of a 4yWxfIJk4yuF4EnqR3z/tYTHhwyieh6n question. Neither these nor questions of logic are hiLd6zlEg4V1bvparx0U8Q== because they cannot be answered by gathering mgZVn1JL8O06aIgaNqgFvwca+UI=.

The key to understanding anything is a combination of observation, especially the quantitative kind of observation we call measurement, and the systematic way of thinking we call logic.

—Peter Atkins (2003, p. 276)

Thinking Critically About Psychological Science

Our analysis of scientific and nonscientific questions teaches a general lesson. Psychology requires critical thinking skills. Critical thinking is the ability to think logically, to question assumptions, to evaluate evidence, and, more generally, to be open-

We’ll try to build your critical thinking skills as we make our way through this book. Ideally, you not only will learn some facts about psychology; you’ll become a “critical consumer” of psychological science.

One method we will use to promote critical thinking is a Think About It feature that you will find throughout the book. It will raise critical questions of the sort a professional psychologist would ask when scrutinizing theory and research. Below is an example.

THINK ABOUT IT

Earlier in this chapter, you read about research showing that, on average, men are slightly more talkative than women. Is that still true? Some of the studies the researchers reviewed were conducted decades ago (recall that the studies took place between 1968 and 2004). Maybe contemporary social changes, such as women’s greater participation in higher education and expanded leadership roles in government and business, have changed the pattern of gender differences observed previously.

13

RESEARCH TOOLKIT

Open-Minded Skepticism

Research in psychology requires specialized tools. Each chapter of this book will highlight one such tool and present it in depth, in a feature called Research Toolkit.

In subsequent chapters, the tool presented in the Research Toolkit will match the specific topic of the chapter. Here in Chapter 1, our topic is psychology as a whole. We’ll thus present a tool that psychologists use no matter what topic they are studying. It is an intellectual tool—

Like the phrase “jumbo shrimp,” “open-

ESP, or extra-

Is ESP real? The vast majority of psychologists don’t think so. But a good scientist is open-

One psychologist recently did this. Daryl Bem, of Cornell University, conducted experiments to see whether people could foretell the future (Bem, 2011). For example, in one study he asked participants to predict whether each of five types of pictures—

Upon learning of Bem’s results, most psychologists were skeptical. They still doubted that ESP exists. Being scientists, they did not merely sit around doubting. Their skepticism motivated them to carry out research of their own.

One research team in the United Kingdom tried three times to replicate the results of one of Bem’s experiments, but couldn’t; their “results failed to provide any evidence” supporting Bem’s ESP claims (Ritchie, Wiseman, & French, 2012, p. 3). A team of researchers in the United States ran seven experiments using Bem’s method and “found no evidence supporting [ESP’s] existence” (Galak et al., 2012). Researchers in the Netherlands reanalyzed Bem’s data (i.e., the numerical summaries of his results) and concluded that his studies never showed that ESP exists in the first place (Wagenmakers et al., 2011). They detected a problem that you, too, may have noticed. Sure, participants seemed to have ESP when it came to the erotic pictures. But what about the other four types of pictures? On those, they showed no sign of ESP at all. When one examines the overall pattern of results—

14

That may be bad news for members of the American Association of Psychics (an actual organization), but the overall set of events is good for psychological science. The combination of open-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 5

Open-