1.2 Psychology as a Science of Person, Mind, and Brain

This chapter’s opening story showed you that psychologists address questions in three ways: by studying (1) persons, (2) the mind, and (3) the brain. Let’s now examine this idea in depth. We will explore the notion of levels of analysis, and then present person, mind, and brain analyses of the same phenomenon: gender differences in performance on math tests.

Levels of Analysis

Preview Question

Question

What characterizes the “levels-

What characterizes the “levels-

Research on persons, the mind, and the brain represents different levels of analysis in psychological science. In any science, levels of analysis are different ways of describing and explaining an object or event. A concrete example clarifies the idea.

Suppose you see an iPhone on which someone is playing a game—

The phone is displaying Angry Birds.

An information-

processing device is carrying out a large series of computer- programming commands. An electronic device is executing electronic input/output operations at a speed of 800 MHz at its central processing unit (CPU).

These three statements reflect different levels of analysis. The level of analysis of Statement A is the phone as a whole (viewed from the perspective of a person using it). The level of analysis of Statement B is computer software; the statement refers to the steps of information processing that take place according to commands in a computer program. The level of analysis of Statement C is electronic hardware; electrons are racing around in the phone’s CPU.

The levels differ considerably. Answers to the question “How does it work?” illustrate how big the differences are. At the level of hardware, the answer is “a silicon chip electronically processes digitized instructions.” At the level of software, the answer is “a series of programming steps displays screen images that are partly based on input from a user.” At the highest level (Statement A), the answer is, “You fling birds with a slingshot and they land on pigs.”

Notice three facts about the levels of analysis:

Each one is correct. You should not be asking, “Which one is the right description of what the phone is doing?” They are all right, in their own way, and complement one another.

15

As you move down a level (from A to B, or B to C), the lower level deepens your understanding of the higher level. How can the phone display Angry Birds (level A)? By executing software programming steps (level B). How can the phone execute all these programming steps (level B)? It is thanks to the device’s fast-

running electronic central processing unit (level C). If you want to understand the phone as a whole, it is best to start “at the top” (the highest level of analysis, A above). If you started at the bottom—

that is, if, hypothetically, you could shrink yourself, climb into the CPU, and see electrons whirring about— you wouldn’t even know, from the electrical activity alone, that the phone was playing Angry Birds.

Levels of analysis in psychology are similar to the levels of analysis in the Angry Birds example:

Person, mind, and brain explanations complement one another; they can each be correct in their own way.

As you move down a level (from person to mind, or mind to brain), the lower level deepens your understanding of the higher level.

It generally is best to start “at the top,” at the person level of analysis. If you started at the bottom—

observing bits of electrical activity at a spot within the brain— you wouldn’t know, from the electrical activity alone, what a person was doing.

Let’s see how levels of analysis work in psychology through an example.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 6

Different levels of XmKN+hFVGlt0jc/5EQ0OBg== complement each other and deepen our understanding of a phenomenon. Of person, mind, and brain levels, if one’s goal is to understand complex psychological phenomena, it is typically best to start at the oxoDeaPOLPhqtQU+ level of analysis.

Once we’ve got a good psychological theory, then it makes sense to ask how the brain does it. … The psychological level of analysis … provides a framework for interpreting the neuroscientific data. Otherwise, it’s all just pixels.

—John Kihlstrom (2006)

A Levels-of-Analysis Example: Gender, Stereotypes, and Math Performance

Preview Question

Question

How can gender differences in math performance be explained at the person, mind, and brain levels?

How can gender differences in math performance be explained at the person, mind, and brain levels?

Our example involves performance on math tests. Research shows that when men and women take math tests that are important to them, fewer women than men attain the highest test scores (Cole, 1997). Gender differences are not always found. Instead, they occur in a specific setting: when people take “high-

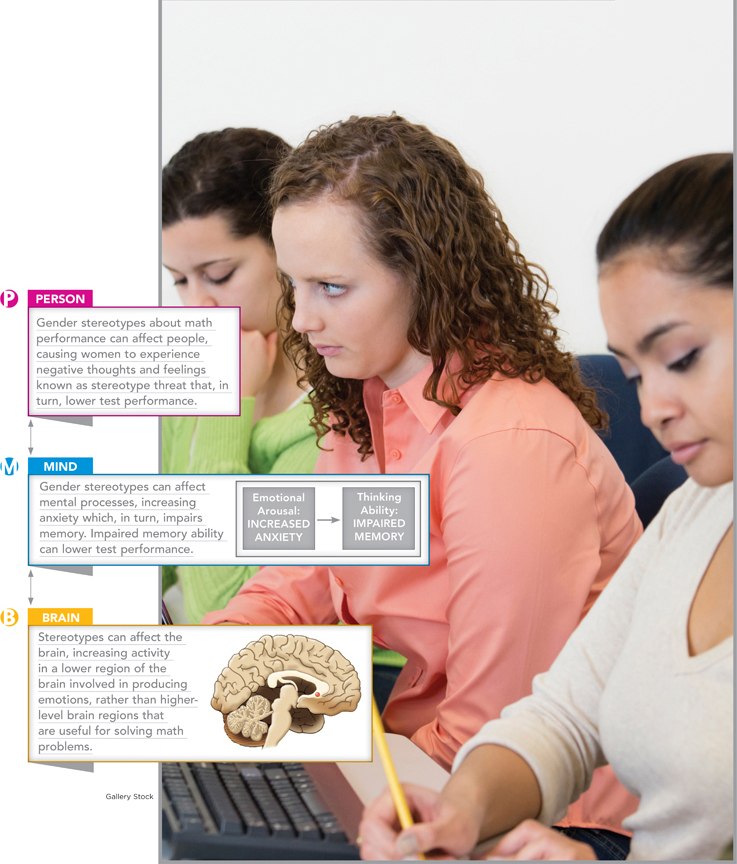

EXPLANATION AT PERSON, MIND, AND BRAIN LEVELS OF ANALYSIS. This question can be answered in three different ways:

Answer 1: One stereotype in our society is that women are not good at math. All women—

16

Answer 2: Good performance on math tests requires not only knowledge of math, but also a calm state of mind. Distressing emotions, such as anxiety, can interfere with the thinking processes (memory, concentration) needed to solve math problems. If women experience more anxiety than men during important math tests, then the influence of emotion on thinking explains the gender difference.

Answer 3: The brain is very complex; different parts of the brain do different things. If parts of the brain that are not useful for solving math problems are highly active during a math test, their activity can interfere with regions of the brain needed for math. This can hurt performance. If women’s brain activity during math tests differs from men’s, then brain activity explains the gender difference in math test performance.

The answers refer to three different aspects of the same phenomenon: people (who experience stereotypes), the mind (in which emotions influence thinking processes), and the brain (and its many subparts). The person, mind, and brain explanations may each be correct and can complement one another. As you move down a level, you get a deeper understanding of the higher level. Why are people affected by stereotypes? It is because, at the level of mental processes, emotions influence thinking. Why do emotions influence thinking? It is because, at the level of the brain, a part of the brain that generates emotions is connected to parts of the brain involved in the logical thinking needed to do math.

Note that the three levels of analysis, although complementary, are not identical. Person and mind differ. People have minds, but the mind is not identical to the person as a whole; there is more to you than just your thinking processes. Mind and brain differ. If you poke around in a human brain, you won’t literally see any thoughts in there, and a brain removed from a body won’t, by itself, be able to do any thinking.

Had you ever considered that the mind and the brain differ?

You (a person) think (a mental, or mind, activity) using your brain (the biological tool needed for thinking). The three answers about women and math tests, then, illustrate distinct person, mind, and brain levels of analysis.

RESEARCH AT PERSON, MIND, AND BRAIN LEVELS OF ANALYSIS. In addition to proposing explanations at different levels of analysis, psychologists also conduct research at each of the three levels—

At a person level, two psychologists (Quinn & Spencer, 2001) ran the following study. They asked men and women to come to a psychology laboratory and take a math test. Some of the men and women simply sat down and took the test. Others first received this information: “Prior use of these problems has shown them to be gender-

In research conducted at a mind level of analysis, psychologists explored the relationship between anxiety and thinking processes (Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001). They expected that, within the minds of all persons, anxiety can impair thinking. To test a this, they asked a group of research participants (1) to report how much anxiety they experience when thinking about math and (2) to try to remember a list of words and numbers. When the researchers related levels of anxiety to accuracy of memory, they found that higher anxiety was associated with worse memory (Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001). Because memory is needed to perform well in math (you have to keep track of the numbers and words in a math problem), high anxiety thus could reduce math performance. This fact about the mind (anxiety can impair memory and thinking) deepens our understanding of the previous fact about people. Why do stereotypes affect people’s scores on math tests? The stereotypes may increase anxiety, which impairs thinking.

17

At our third level of analysis, a team of psychologists (Krendl et al., 2008) studied women’s brain activity during math tests by using brain-

On what kinds of tasks might you experience heightened anxiety and reduced memory capacity?

The study produced two findings. First, stereotypes influenced performance; women who heard the stereotype-

Factors in addition to stereotypes can affect math performance and contribute to gender differences. Men and women may differ in their level of interest in math, in specific mental abilities (including abilities that enable people to succeed in nonmathematical fields), and in brain structure and functioning (Ceci, Williams, & Barnett, 2009; Stoet & Geary, 2012). Most psychological phenomena are affected by many factors, and math performance is no exception. Nonetheless, research on how stereotypes can affect persons, the mind, and the brain shows how different levels of explanation can combine to provide multilevel understanding in psychological science.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?

Question 7

Research at the p2cr5/UVOEiSjqsV level of analysis deepens our understanding of the effect of gender stereotypes on math performance by showing that anxiety impairs mo3uXg2Yxx8yE0z5. Research at the DFWnZgt9nnTSLKGc level deepens our understanding further by demonstrating that stereotypes activate brain regions associated with x5Hc2GrqoMbWrq3UPjUohQ==, rather than those useful for math processing.

Earlier in this chapter, you tried our first Try This! exercise. If you didn’t, do it now; it’s at www.pmbpsychology.com. Let’s review what you learned.

Our first Try This! teaches a valuable lesson about the power of scientific methods, which can provide knowledge that exceeds what one knows from intuition alone.

18

19

TRY THIS!

Intuitively, you probably thought that the only way in which memory could be flawed is that you might forget information you saw previously. But thanks to Try This!, you learn of the existence of another type of flaw: “remembering” information you did not see previously. When trying to remember words presented on a list, many people have the experience of recalling a word that was not actually present. The carefully constructed research methods of the Try This! exercise (Roediger & McDermott, 1995) convincingly demonstrate this fascinating and surprising fact about memory.

At this point in your reading, you also should be able to identify the level of analysis at which the Try This! exercise was conducted. It was at a mind level of analysis; the study reveals a property of the mind, namely, a memory error. You will learn more about the mind, and its powers—

Each chapter of this book contains a PMB in Action feature like this one. PMB in Action shows you how a given question (in this case, “How do gender stereotypes affect test performance?”) can be answered at each of three levels of analysis: person, mind, and brain.

Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain: An Overview

You will encounter person, mind, and brain analyses throughout this book; this is why it is titled Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain. The book’s organization reflects activity in the twenty-

This book reflects psychology’s multilevel nature in two ways:

Individual chapters: Each chapter begins with a story about the behavior and experiences of a person. Our effort, in each chapter, is to introduce you first to the human experiences that motivate psychologists to study the material covered in that chapter. Once we do this, we’ll move down to mind and brain levels of analysis, to see how research on mental systems and brain mechanisms deepens the scientific understanding of people. Coverage of the brain generally is found in the later sections of any given chapter. You’ll thus be learning about brain research only after first learning about the psychological phenomena that researchers are trying to understand by studying the brain.

The book as a whole. This book has four parts. Here in the initial part, the current chapter introduces the field and Chapter 2 acquaints you with its main research methods. The other three parts of the book—

Brain, Mind, and Person— cover parts of the field in which research at brain, mind, and person levels of analysis predominates. Individual chapters within each part focus on specific topics in psychological science: for example, how we perceive the world; factors that affect our level of motivation; how individuals develop psychologically from childhood through adulthood; and how therapy can help people who are experiencing psychological disorders. The brain, mind, and person parts can be read in any order; Chapters 1 and 2 provide enough background that you can move directly to any of the other parts of the book.

Learning that your psychology book has separate parts, each with chapters on separate topics, can create a false impression. It might appear that psychology is a collection of isolated subfields that have little to do with one another. This is not the case. Especially in recent years, psychology has become a highly integrated science, with different parts of the field informing one another. The levels of analysis we have discussed are key to this integration. Researchers in different branches of the field commonly explore, at different levels, the same psychological phenomenon. Their research results thus inform one another. Consider this example.

20

Psychologists are interested in self-

At a person level, personality psychologists identify individual differences in self-

control abilities that are evident early in life and persist into adolescence and adulthood (Chapter 13). At a mind level, memory researchers find there is a mental system with “executive” abilities that can control the flow of thoughts and emotions (Chapter 6).

At a brain level, researchers find that interconnected brain regions are active when self-

control is exerted (Chapter 3); one brain region regulates activity in another.

Research in these different areas combines to yield a coherent portrait of how the brain and mind enable people to exert self-

Throughout this book, we will highlight these interconnections among different branches of psychology. A PMB Connections feature will show you how research studies conducted at one level of analysis connect to studies conducted at other levels of analysis, which are presented elsewhere in the text.