6.2 Levels of Analysis: Memory and Mind

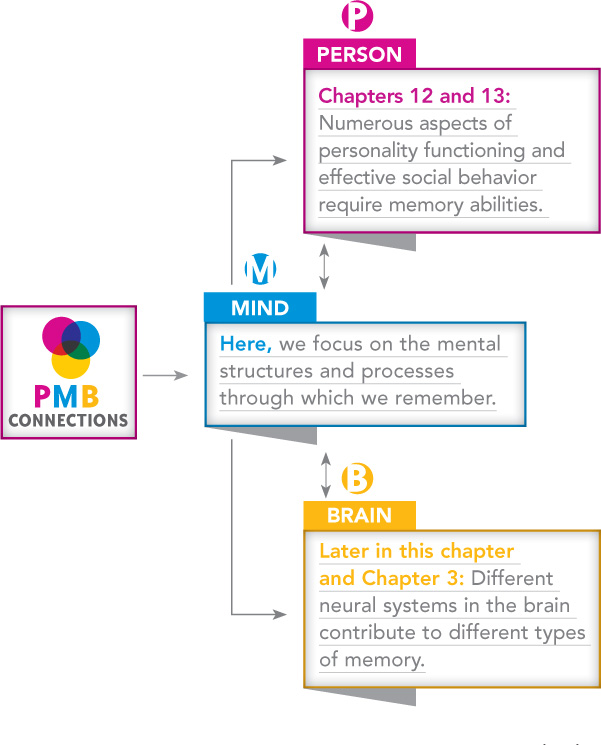

How can psychology explain people’s ability to remember information? You learned in Chapter 1 that psychologists formulate scientific explanations at three levels of analysis: person, mind, and brain. Let’s see how each might help to explain the following simple example.

CONNECTING TO THE BRAIN, PERSONALITY, AND SOCIAL BEHAVIOR

One day in class, your psychology instructor briefly flashes up on screen the following: “Exam: Next Tuesday. Textbook Coverage: Chapters 7, 8, and 9.”

A few days later, you think to yourself: “They said something in class about a psych exam, didn’t they? Maybe I should have put it in my calendar. Hmm, what was it?” After some mental effort, you remember “Tuesday” and “Chapters, 7, 8, and 9.” How can psychology explain this ability to remember?

A person level of analysis might identify personality factors or social influences that affect memory. For example, if you are highly motivated to excel in the class, you might tend to remember the information. If you were distracted (e.g., by a text message) when the information appeared, you might not remember it.

A brain level of analysis would refer to neural systems you use when remembering information. Researchers would try to identify biological mechanisms whose functioning is required in order for people to remember anything.

Person and brain levels of analysis are informative; but when it comes to the study of memory, they are incomplete. The person level does not explain how memory works: the processes and structures that enable a person to remember material. The brain level provides biological information, but may fail to provide the psychological information needed to fully understand memory. Consider the results when one research team obtained brain images during a memory task (Miller et al., 2002). The brain activity of participants varied substantially from one person to another—

Explanations at a mind level of analysis refer to processes of thinking and to information that people acquire, retain, and draw upon when they think. Psychologists working at a mind level of analysis try to answer questions such as the following: How do people detect information in the environment (e.g., information such as “Exam, Tuesday, Chapters 7, 8, and 9”)? Where and how do they store information after they detect it? How long does information remain in memory once it is stored? How do people retrieve stored information when they need it? Such questions are at the heart of mind-

Historically, research at a mind level of analysis was inspired by developments in computer science. Psychologists drew an analogy between computers and the human mind (Newell & Simon, 1961). A computer is built of electronic hardware but runs software—

217

In the rest of this chapter, we will follow their lead. We first will focus on memory and the mind: mental processes that enable you to retain information. Then, at the end of the chapter, we’ll explore memory and the brain.

THINK ABOUT IT

The analogy between (1) the human mind and (2) a computer was valuable to cognitive psychologists studying memory. But no analogy is perfect. Are there some ways in which the human mind is not like a computer? Does your computer get emotional? Does it know it’s a computer?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 2

It is possible to understand memory by studying processes at the p2cr5/UVOEiSjqsV level of analysis even if we do not yet understand those processes at the DFWnZgt9nnTSLKGc level of analysis.