11.2 Biological Needs and Motivation

All organisms must meet biological needs. They need, at minimum, to survive and to reproduce. You already are familiar with the relevant biological mechanisms. Organisms meet survival needs by transferring material between themselves and the environment, bringing in environmental nutrients (food, drink) and excreting bodily waste. Most complex species meet reproduction needs by transferring material between two organisms: a male and female engaging in sex, with sperm and egg uniting and developing into an embryo.

That is the biology. Here, we are interested in the psychology; we need to identify the psychological processes that motivate organisms to meet these biological needs. We’ll do so starting with the need for food, the behavior of eating, and the psychological experience of hunger.

Hunger and Eating

Preview Questions

Question

Does hunger alone motivate us to eat?

Does hunger alone motivate us to eat?

What characterizes eating disorders? What causes them?

What characterizes eating disorders? What causes them?

What motivates an organism to eat? Part of the answer is hunger, a feeling of food deprivation that motivates organisms to seek food. The psychological experience of hunger is created by biological systems in the body and brain. When the body needs nutrients, biochemicals circulating throughout the body signal a brain structure known as the hypothalamus (see Chapter 3). The hypothalamus, in turn, sends out biochemical signals that create the experience of hunger (Goldstone, 2006). When we have eaten enough, the hypothalamus sends signals that result in satiety, a feeling of having enough food, or being “full.”

How soon after you experience satiety do you typically stop eating?

461

It sounds simple: When the body needs nutrients, we experience hunger and eat; when we have enough nutrients, we experience satiety and stop. But, as often occurs with simple stories in psychological science, the story is too simple. The true story of eating and hunger is more complex, both psychologically and biologically (Berridge, 2004). One main complication is that there is not one, but two types of hunger (Lowe & Butryn, 2007): homeostatic hunger and hedonic hunger.

HOMEOSTASIS. Homeostasis is the maintenance of a stable state. Homeostatic processes, then, are processes that maintain stability. For example, a thermostat maintains stable room temperature by detecting current temperature and activating heating or air conditioning systems when that temperature deviates from a desired temperature.

Homeostatic hunger is a motivation to eat that is based on the body’s need for energy (Lowe & Butryn, 2007). If you go for a long time without food, your body, as noted above, detects the lack of energy and produces feelings of hunger that motivate you to eat. The eating maintains energy homeostasis, that is, a stable supply of bodily energy (Woods et al., 2000). According to set-

However, set-

Have you ever had a big meal in a restaurant—

perhaps the double cheeseburger or the spaghetti and meatballs— and then ordered a dessert? And then eaten it? That behavior raises problems for a set- point analysis. Having finished the main course, you couldn’t have been experiencing homeostatic hunger; the meal provided plenty of calories. Yet, contrary to what set- point theory would predict, you were motivated to eat dessert. 462

Have you ever been so busy—

working the holiday rush in a store, finishing a paper due the next morning— that you forgot to eat? People commonly report being so busy that they didn’t even notice any hunger pangs (Herman, Fitzgerald, & Polivy, 2003). Again, this violates the assumptions of set- point theory. When busy, people burn up more energy than usual, which should put them below their set point. Yet they still might forget to eat.

HEDONISM. There is a second motive to eat, and it’s simple: Food tastes good. Even when people do not need more calories, they are motivated to eat because eating high-quality food is pleasurable. Hedonic hunger arises from the anticipated pleasure of eating good food (Lowe & Butryn, 2007). When it looks good, you’ll order dessert—

From an evolutionary perspective, hedonic hunger makes a lot of sense (Pinel et al., 2000). Consider the distant evolutionary past, when all humans hunted animals and foraged for edible foods. The food supply was unpredictable. Eating only when homeostatically hungry—

Evidence that factors beyond homeostasis motivate eating comes from a study of two patients with amnesia (Rozin et al., 1998). On each of a series of days, researchers offered them lunch, engaged them in conversation, offered them lunch again, engaged them in conversation again, and then offered them a third lunch. Being amnesic, they did not remember having already eaten when the subsequent lunches were offered. If eating were controlled by homeostatic signals, signals of satiety would have caused them to refuse the second and third lunches. But, instead, they ate again! On most days, the patients consumed most of the second lunch and much of the third (Rozin et al., 1998).

Although the hedonistic “eat tasty food whenever available” strategy might have been good in the distant past, today it has drawbacks. In contemporary industrialized societies, most people can readily access food. Wherever you are right now, you probably have eaten recently (i.e., within the past few hours) and are near a food source (refrigerator, supermarket, restaurant, vending machine). The evolved tendency to stock up on food, combined with a plentiful supply of tasty foods in the contemporary world’s “food-

EATING DISORDERS. The two types of hunger—

463

There are three types of eating disorders: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder (Heaner & Walsh, 2013; National Institute of Mental Health, 2011).

People with anorexia nervosa are so fearful of being fat that they starve themselves; they severely restrict their intake of food in order to attain thinness. The restrictions can be so severe that they create physical problems such as bone thinning and a loss of muscle mass. Despite being objectively thin, people with anorexia nervosa often see themselves as overweight and are dissatisfied with their bodies (Cash & Deagle, 1997).

People with bulimia nervosa exhibit a pattern of eating that fluctuates dramatically. They binge and then purge; that is, they eat uncontrollably large amounts of food (binging) and then try to avoid weight gain by getting rid of it (purging), often through self-

induced vomiting. Bulimia’s binge– purge cycle creates numerous medical problems, including dehydration, tooth decay (from repeated exposure to stomach acids), and disruptions of the body’s internal chemistry (National Institute of Mental Health, 2011). People with binge eating disorder repeatedly eat excessively large amounts of food, as is seen in bulimia nervosa. But, unlike people with bulimia, those with binge eating disorder do not purge. The binge eating pattern thus causes obesity.

When eating disorders strike, they usually begin in the teenage years or early adulthood. Surveys suggest that 0.5 to 1% of people experience anorexia or bulimia and that rates of binge eating disorder are about twice as high (Kessler et al., 2013; Preti et al., 2009). The disorders are much more common among women than men.

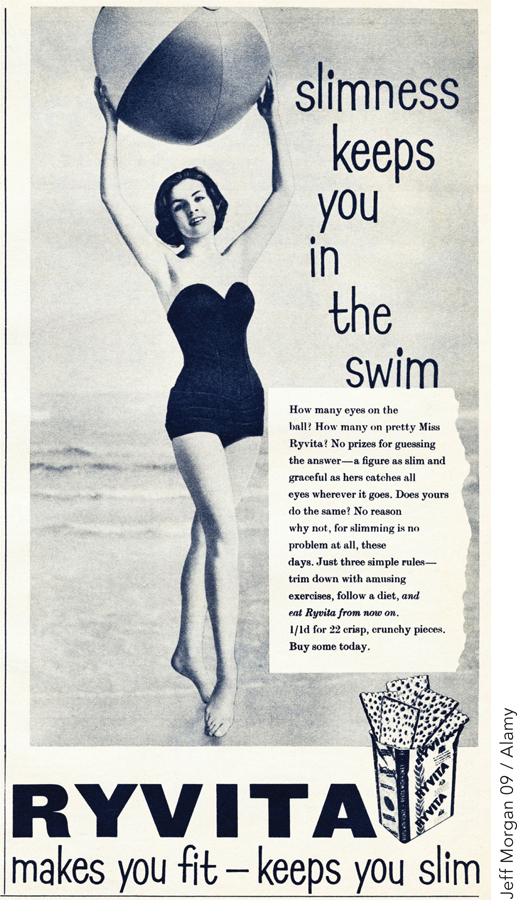

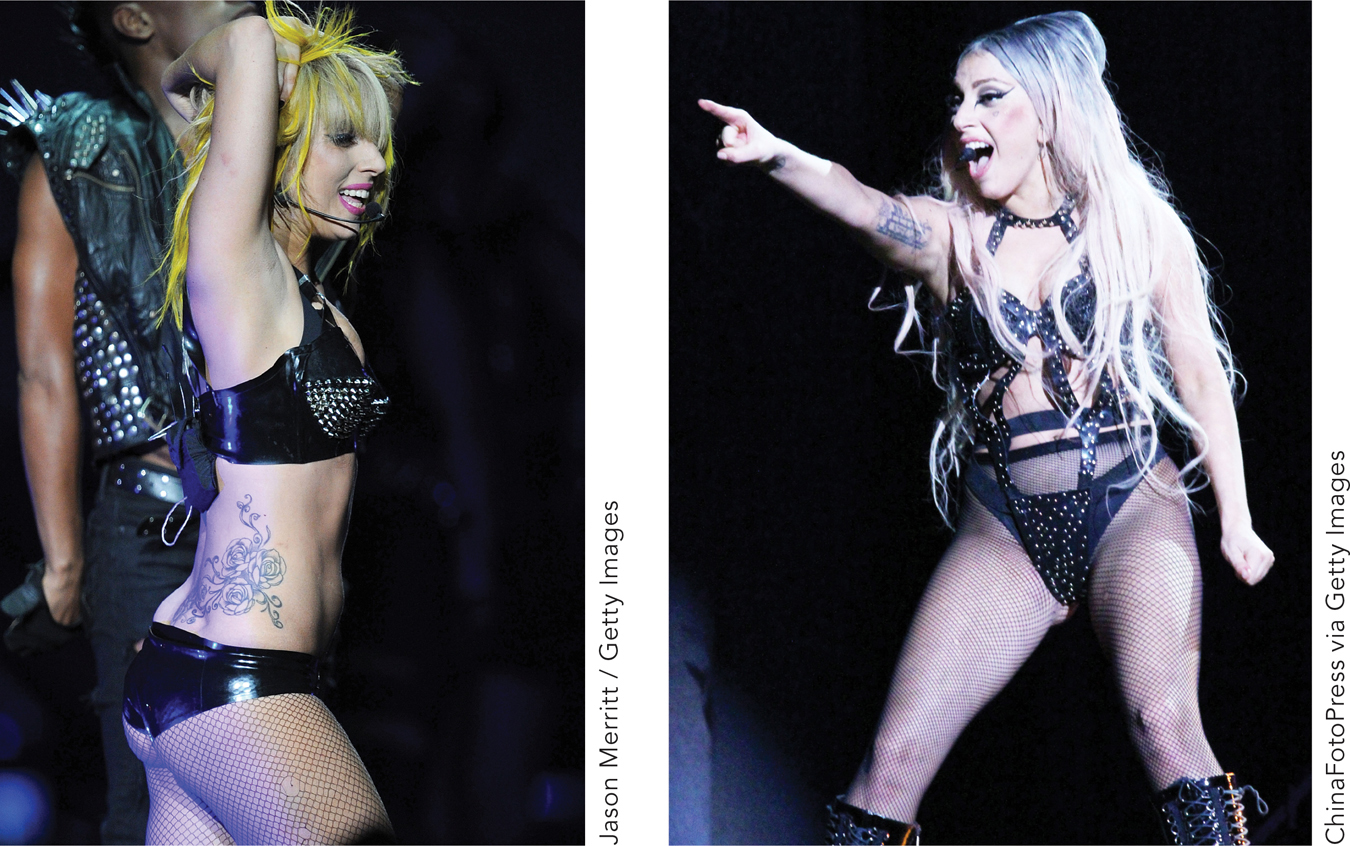

What causes eating disorders? In particular, why do some people take dramatic measures (e.g., starving themselves, purging) to reduce their intake of calories? There are a number of possible reasons. One is social. Society surrounds people—

Another potential cause lies in the family environment. Parents who criticize their children’s appearance and demand that they be thin may contribute to the development of eating disorders (Polivy & Herman, 2002). However, when eating disorders occur, parents are not necessarily to blame. Researchers emphasize that parenting is only one of a large number of factors that can contribute to eating disorders and that no one parenting style is strongly linked to their occurrence (Le Grange et al., 2010).

THINK ABOUT IT

Media images of thinness contribute to eating disorders. But do media influences fully explain why the disorders occur? Virtually everyone is exposed to images of thinness in ads, movies, and TV shows, yet only a small percentage of people experience eating disorders. There must therefore be other factors at play.

Finally, a psychological factor that can contribute to the development of eating disorders is perfectionism, that is, a general tendency to strive to fully meet high standards of excellence. The psychotherapist Hilde Bruch (1973) argued that many girls become obsessed with meeting other people’s goals for them; they strive to be a “perfect child.” Controlling one’s eating can become a way of achieving this sense of perfection. Findings suggest that people who are more perfectionistic are more vulnerable to experiencing eating disorders (Bardone-

464

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 2

Contrary to set-

Sexual Desire

Preview Questions

Question

How does sexual motivation differ from the motivation to eat?

How does sexual motivation differ from the motivation to eat?

What is the biological basis of sexual desire?

What is the biological basis of sexual desire?

Sex, like hunger, is biologically basic. Humans and other animals desire, pursue, and enjoy sexual activity. The reason is obvious: In the evolutionary past, organisms who were motivated for sex out-

Although the motivations for both food and sex are biological basics, they differ in two main ways. First, unlike our need for food, we do not literally need sex. Without food, you die. Without sex, you could get by. Many celebrated historical figures have been celibate—

DIVERSITY IN SEXUAL DESIRE. A second way that sexual motivation differs from hunger is its diversity. Hunger motivates one type of behavior, the eating of food. But sexual motivation is diverse in four ways:

Diversity of people toward whom sexual desires are directed. Most adults are sexually attracted to members of the opposite sex; in one representative survey of young adults, about 94% of men and 84% of women described themselves as “100% heterosexual” (Savin-

Williams, Joyner, & Rieger, 2012). Those numbers, though large, are far from 100%; many people find members of their same sex to be sexually arousing. (Chapter 4 discusses biological and environmental factors that contribute to diversity in sexual orientation.) 465

An entirely different type of diversity is seen in cases of sexual deviance in which desires are directed toward nonhuman objects or nonconsenting individuals (Kafka, 2010). A particularly problematic form of sexual deviance is pedophilia, in which adult sexual motivations are directed toward children (Fagan et al., 2002).

Diversity of stimuli that trigger sexual arousal. The biological purpose of sex is reproduction, yet stimuli that have little or nothing to do with reproduction can trigger sexual arousal. Research on fetishism, sexual arousal in which stimuli that typically are not sexual in nature stir desires (Kafka, 2010), illustrates the point. A survey of Yahoo! discussion groups revealed 2938 groups whose publicly available information included the word “fetish” (Scorolli et al., 2007). Tens of thousands of group members were discussing their sexual attraction to stimuli such as body parts (e.g., feet, hair) and articles of clothing (stockings, shoes, boots, costumes).

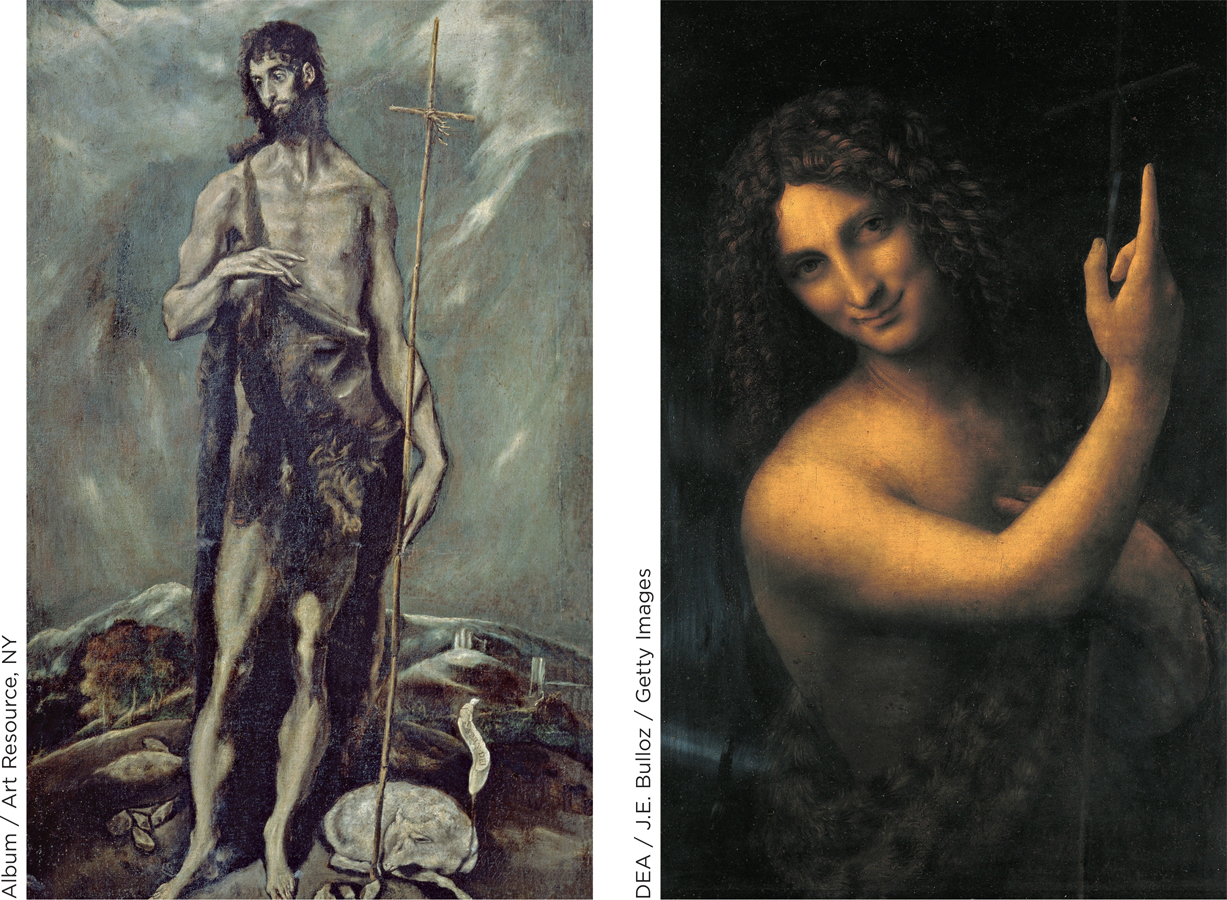

Diversity of activities motivated by sexual desires. Sexual desires may motivate a diverse range of behaviors that are not inherently sexual. Sigmund Freud (1900) famously proposed that the human mind redirects sexual energy to nonsexual activities (also see Westen, 1999). According to Freud, when sexual activity is unavailable or prohibited, the sexual energies build in pressure and must be released. A writer whose sexual energies are frustrated may redirect them into the writing of love poems. A painter or sculptor may use sexual energies to power the many hours of activity required to produce a great work of art.

Diversity of reasons for having sex. Why do people eat? To consume tasty foods. Why do people have sex? There’s no shortage of reasons. Investigators who asked a large number of men and women why they have sex identified 237 reasons in the responses (Meston & Buss, 2007, 2009). In addition to obvious ones, such as the sensual pleasure of sexual activity, participants cited reasons such as relieving boredom, punishing an unfaithful partner, attaining a job promotion, making someone jealous, improving a partner’s emotional state, and (last but not least) expressing affection and love.

466

What accounts for the diversity of human sexuality? There are two “sides” to human sexual life (Tolman & Diamond, 2001). First is the biological side that we share with other species. Animals (including us) inherit biological mechanisms that impel sexual desire. Second, there is a social side. Unlike other animals, humans’ sexual activities are suffused with social meaning: worries about your partner’s enjoyment of the activity; concerns about your own attractiveness and performance; age-

SEXUAL DESIRE AND HORMONES. Despite these social aspects of human sexuality, however, sexual motivation does have a core biological foundation: hormones, the chemical messengers that travel through the bloodstream and activate biological processes in the body (see Chapter 3). A hormone central to sexual life is testosterone, which is produced in the gonads—

Testosterone’s role in sexual motivation is evident from studies that manipulate testosterone levels experimentally. This is done medically to treat hypogonadism, a condition in which the body produces too little testosterone. Among adult men, hypogonadism results in low levels of sexual motivation; additional symptoms include reduced facial hair growth and muscle mass. When testosterone is administered to people with hypogonadism, these symptoms reverse. In one study, patients received testosterone on a daily basis for six months. After 30 days, their sexual motivation increased. Men reported more frequent sexual daydreams, flirting, and sexual interactions (Wang et al., 2000). Similar results have been obtained among women reporting low levels of sexual desire. Compared with women in a placebo drug condition, those receiving daily doses of testosterone reported more sexual desire, as well as more arousal during sexual activities (Buster et al., 2005).

Just as you need gasoline to fuel a car, you need testosterone to fuel sexual motivation. Once you’ve got some gas in your car, though, varying levels of gas (a quarter tank, half a tank, etc.) do not make your engine more or less powerful. Similarly, once hormone levels are in a normal range, variations in testosterone are relatively unrelated to levels of sexual activity. Research with couples finds that although women’s testosterone levels are correlated with their frequency of sexual experience, men’s levels are unrelated to the couple’s frequency and quality of sexual experiences. Sexual experiences reflect the quality of the couple’s interpersonal relationship, not variations in hormone levels (Zitzmann & Nieschlag, 2001).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 3

True or False?

- Ca34tlc8Zsqb49egOWFO/sj1k+pzvfIHs0j6nOfFkGn0iGtCYSLrLcGL51C28OpPzwspgZwj4srvc+74H5WmfeG6VpR0U1/Y9sx7UW1hsK/74ea4g2BtP8UF8lo1uGOy6d2zkcbRVYn/XIraojfpOkg1N1UNUZrCT6L6tNjz1EK0ORP9Nga5Agir++YNUpjlw8FosysvZcYGEsb0oMGQ/2L1PM2u6/Maou1QvQ==

- hOOhyH3VSb/5sF6NZJmf1V8g5V5j8SCSxKxyhIjsJS1XtZRSbFsb70Gr4a0sInaqFY1MQ7Z46wrVtKm1AOU5gMubmOrQgknnu06sHzJqMGy8WgsKIW1YWj6Tp0PwPBO6ILQXfkJIAxNsGet/AdoOUyGbJ2CjeoRjNtvETX4qGSDnrgTM0moOyy4TYPU4WOrZmmFayTHK8i1kMTrmC7JXGByIQ+2zICiH