11.4 Social Needs

Biological needs serve the body. Achievement needs fuel activity on challenging physical, intellectual, and professional tasks. But people live in a social world. Thus, they also are motivated by social needs, that is, desires that motivate us to interact with others and to achieve a meaningful role in society.

You often can feel your own social needs. You might be sitting at home, perfectly safe, snacks in the refrigerator, after a week of work. Your biological needs are met. Your work achievements are complete. Yet you want more. You want to hang out with your friends; to see a movie; to start a new relationship; to be involved in your community. These are your social needs.

Many psychologists have, over the years, tried to develop a comprehensive list of social needs (e.g., Murray, 1938). The job is difficult, especially because the needs that people experience may vary from culture to culture. Despite these difficulties, many contemporary psychologists (e.g., Fiske, 2009; Ryan & Deci, 2000) judge that five social needs are universally important to human motivation: needs for (1) belonging, (2) understanding, (3) mastery and control, (4) enhancing the self, and (5) trusting. (These needs overlap somewhat with the ones proposed by Maslow, discussed earlier. However, unlike Maslow, most contemporary psychologists do not think that the needs are arranged in a fixed hierarchy.)

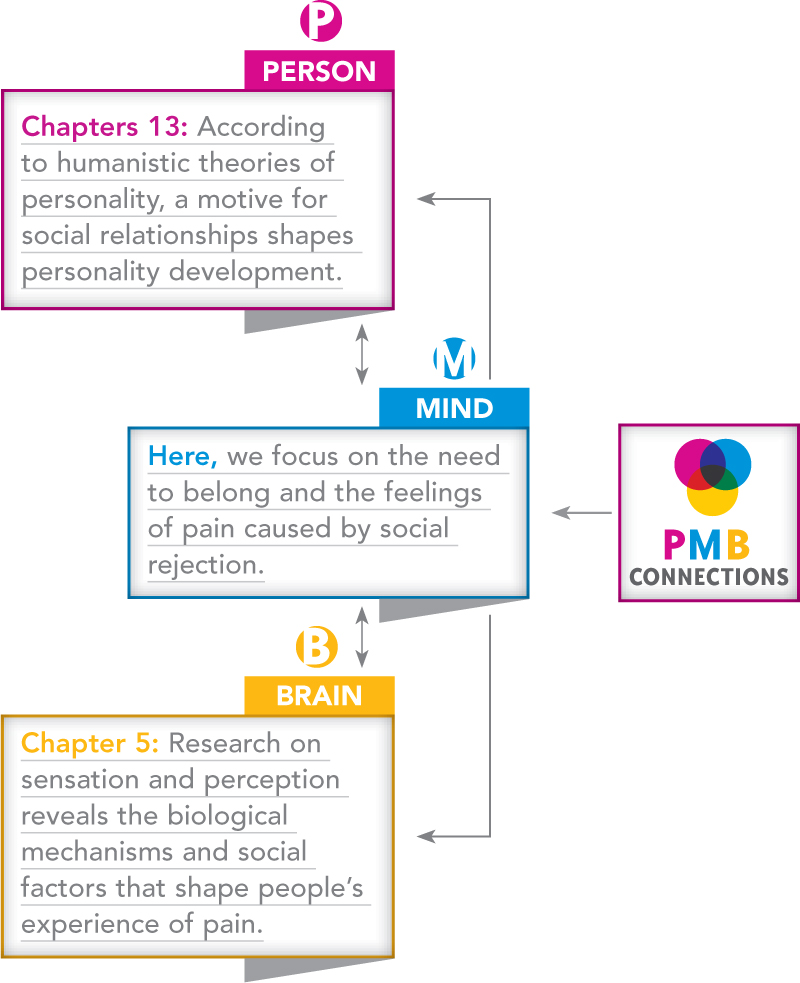

CONNECTING TO SENSATION AND PERCEPTION AND TO PERSONALITY DEVELOPMENT

Belonging

Preview Question

Question

Does everyone feel the need to belong?

Does everyone feel the need to belong?

“No man is an island.” The poet John Donne’s sentence is one of the most famous phrases in English literature, and for good reason. Donne captured an essential fact of human life: Psychologically, people need to live among others. Loneliness can be unbearable. A social need for belonging motivates people to spend time with other individuals and to become part of social groups.

Research suggests that this need is universal. People in all societies and cultures experience the need for belonging. To fulfill this need, people the world over form enduring social relationships and try to maintain the relationships they have established (Baumeister & Leary, 1995).

The need for belonging is so powerful that failing to fulfill it is painful—

What have you done recently to maintain any of your social relationships?

470

Many argue that our contemporary need to belong is rooted in our evolutionary past. Tens of thousands of years ago, early humans faced harsh living conditions, such as ice ages that threatened the species’ survival. To cope, people banded together into groups. Rather than living as isolated individuals or small families, they formed larger units that, through group efforts, were better able to battle the elements (Morris, 2010). A desire to belong to such groups was therefore an evolutionary advantage. People who felt a need to belong benefited from the advantages of group living. Individuals who were not motivated to live in social groups missed out on these benefits, and thus were less likely to survive. Thanks to evolution through natural selection, then, we contemporary humans inherit a need to belong (Hogan, 1983).

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 6

For each of the “answers” below, provide the question. The first one is done for you.

Answer: Poet John Donne’s famous quotation about human social needs. Question: What is “No man is an island”?

- eMAcUwlFF8TkTe1Sf8pq4JV8kTEMU696DOeA4lSVweSiVxbMXgZ/H704NOdjREgecFc9kA3HXIdFsL1jeWI/jLgKrppBwBvz26Yw4w4qSUfSeKZBrROwQDif9UeS0jtS/ZHjX1kGt3xEh2B8YozAGxQabCT9/B/IgDQS7xhvYEarxL/H9pM2uU7F9F/ymVeNtjRPUvOeRrw=

- 0mgYb5i+W//vXUtta2mUW7+0wt5qH9JxuUiyRrkcov+xC3njilaZ1POYSPsUdHa7/Ih0lVcyPdkLl5R5rpVTHXf8g4Ocz9CBemrduaVhQBseag4YFXpaG84JthSfE6z4jLydlKg/YXXFQJKb5Uq3E9qW4XDGRWlR83G5jbY/jn3ivz81q3orQ1Dnb2r4MmLfkRUEMlbWI3OmqMlqAvCiZpmGv+HfTiFEduktUC0g0puigr3V/y2Ty+L11RoyeAPcByv1zHlhADT44bM8+F4FQotQYzPxuuJCpPdn4w==

b. What is the need for belonging? c. What is physical pain?

Understanding

Preview Question

Question

Are we satisfied with a vague understanding of events?

Are we satisfied with a vague understanding of events?

A second social need is a need for understanding, that is, a motive to comprehend why events occur and to predict what the future might bring.

If you reflect on your own thoughts, you’ll quickly recognize this need in yourself. What sorts of thoughts tend to run through your head? If you’re like most people, many of them are efforts at understanding. Suppose a friend cancels plans to get together. You want to understand why. If your parents say they want to visit you next weekend, you want to understand why. We’re like detectives: When things happen, we put together clues, think about other people’s thoughts, and try to find out what causes the events of our lives.

The need for understanding is a social need in that we rely on others for knowledge. We gain information and figure out the meanings of events by interacting with other people in person and electronically (Kruglanski et al., 2006). In fact, one of the major topics explored in social psychology (see Chapter 12) is a form of thinking fueled by the need for understanding: attributions, or thoughts about the causes of people’s social behavior.

People often seek a particular type of understanding. They want to achieve not merely a vague grasp of events, but cognitive closure: a firm, definitive understanding grounded in information that resolves ambiguities and eliminates confusions about events (Kruglanski & Webster, 1996). Although some people are more bothered by uncertainty than others, people generally prefer to reach closure on issues, that is, to resolve puzzles, get missing information, and gain a firm understanding of the world around them.

471

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 7

The need for understanding is ultimately a kcxsDC5VTGkSiECZ need, because we rely on others for knowledge. Cognitive Y4Pr02hWXtfkBKDB is a particular type of need for understanding aimed at eliminating confusion and resolving ambiguities.

Control

Preview Question

Question

How do we benefit from having control over outcomes?

How do we benefit from having control over outcomes?

Who should decide what clothes you wear, how long your hair is, and who your friends are? Most people would say “I should.” You may not mind if others offer some opinions, but you want to be the final decision maker. People have a need for control.

The need for control is a desire to select one’s life activities and to have the capacity to influence environmental events (Leotti, Iyengar, & Ochsner, 2010). Some suggest that two distinct needs are at play in the overall need for control: (1) a need for autonomy, that is, a need to direct and organize one’s own activities so they are consistent with one’s inner sense of self (Ryan & Deci, 2000); and (2) a need for mastery, that is, to be competent and able to influence events.

You may have felt your own need for autonomy in school. Did you ever have a teacher who issued a lot of commands, set a lot of deadlines, and thus gave students little choice in what to do, and how and when to do it? Teachers who reduce students’ autonomy in this way may lower motivation. Students are found to be more interested in school material when they have more choices and options—

The need for mastery is evident in many areas of life. One is coping with health problems. Studies of cancer patients, for example, reveal that after receiving their diagnosis, people differ in how they respond psychologically. Those who respond with strong feelings of mastery—

Think about an upcoming exam. To what extent do you feel you have mastery over its outcome?

Conversely, a lack of control can reduce well-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 8

5l4cC/Uez6zlDhKFF5JKN44p31txj7gwnH4pE56tlPhDNQKmfAAN9Wv+4rpjEwalyu0jLWgywGWxygrGntuv2lf10EIEM02irDsewePPArJl1zRHHoFEe1ebHg4idwVh1lDJ0aPfc3wcz08B0okYQJM1+duYE1TFXx2yRn3DY7Z04ZFkBoxmdXgI+98=Enhancing the Self

Preview Question

Question

What kinds of behaviors are explained by the need to enhance the self?

What kinds of behaviors are explained by the need to enhance the self?

A fourth social need is the need to enhance the self, that is, to grow as a person, to develop a life that is psychologically meaningful and potentially beneficial to others, and to realize your true potential. Personality theorists such as Carl Rogers (see Chapter 13) and, as you saw earlier, the motivation theorist Abraham Maslow referred to this need as a motive for self-

472

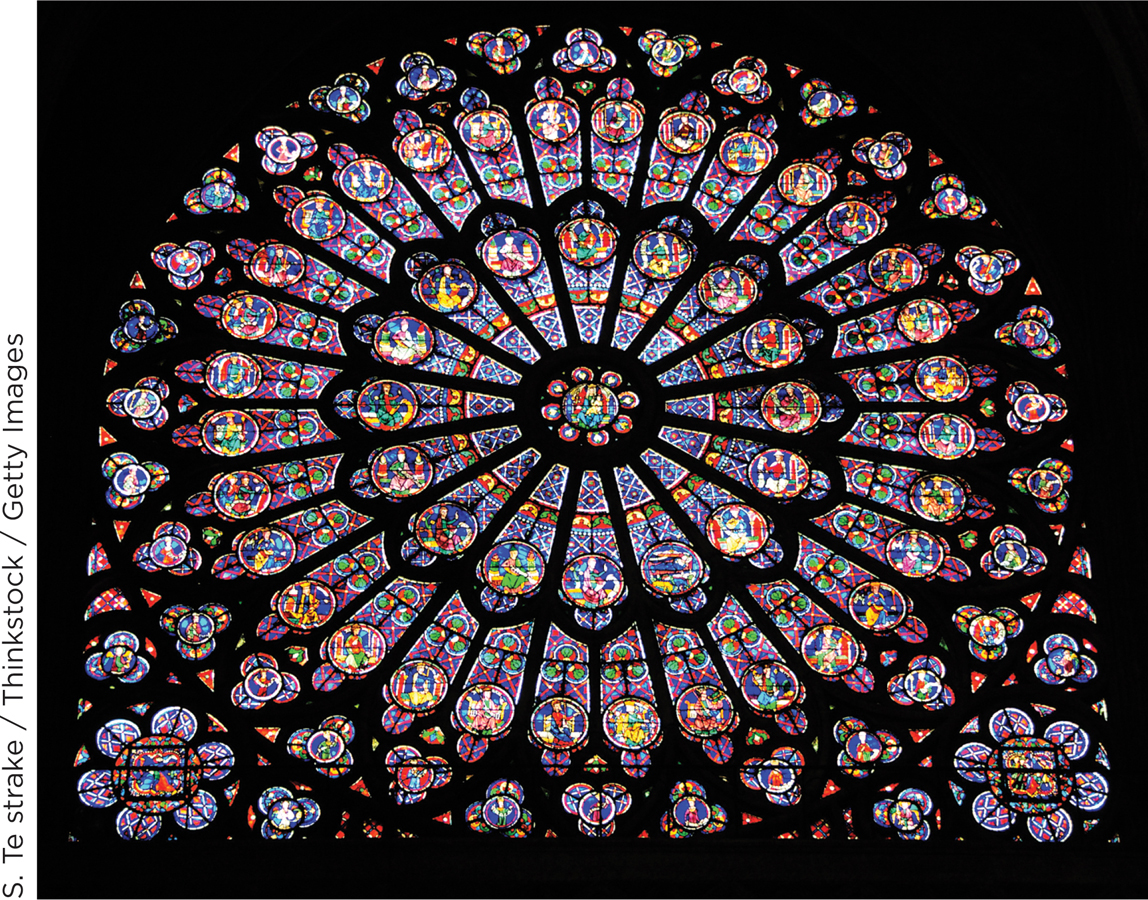

The desire to enhance, or actualize, the self explains behavior that otherwise would be puzzling. Consider the effort that billions of people, throughout world history, have invested in religious practices. In medieval Europe, for example, most citizens lived in relative poverty, yet societies spent hundreds of millions of dollars (in contemporary currency) building each of Europe’s great cathedrals (Scott, 2003). If people were driven solely by biological needs, this behavior would be inexplicable; you’d expect societies to expend money exclusively on food and shelter. The psychologist Carl Jung suggested, however, that people’s desire to understand themselves and their place in the universe motivated these vast, costly efforts (Jung, 1964). In the contemporary world, people’s personal goals in life frequently include aims that are directly or indirectly related to spiritualism (e.g., “live my life at all times for God,” “approach life with mystery and awe”; Emmons, 2005, p. 736). Spiritual goals, Robert Emmons (2005) suggests, provide a sense of meaning in life, and thus contribute to an integrated, coherent sense of self.

Needs to enhance the self can be a source of motivation that benefits others. People can attain meaning in their own life by contributing to others’ welfare—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 9

cuLXlODYgn/klRUieivMzmbIrg8cotjJh9UCavZgbVjZRTvfXfc5k37CM0Gc/Q4fejzLwI6YN2qpVYvMoXk7WvKA/6gazY0kJ8j8St821/c0h/FN8ZyXSR3bm4qCf5zvDTbAFfZgI1GZ9jRYxsqW2wPO6YRd4Xcrs4P/m2mhq7Ojub50C+CIkDC9OavJIou65SJL+EbNMB5dObAdO8qzykpIoWJB8GRjoc9z++sM6b83TdQlNAsaXRuEmgvh1efKyfTNbBllpH4glioEW8GdC2xa/DU=Trust

Preview Questions

Question

What are everyday examples of our uniquely human need for trust?

What are everyday examples of our uniquely human need for trust?

What is the biological basis of trust?

What is the biological basis of trust?

A fifth social need is trust. Many psychologists argue that people have a basic need to trust in their fellow humans beings (Fiske, 2009; Kosfeld et al., 2005).

IN STRANGERS WE TRUST. At first, the idea that trust is a universal need might sound puzzling. When a car salesman says he has “a great deal” for you or a dating partner says he has a “good excuse” for showing up an hour late, you feel suspicion rather than trust. Nonetheless, much of everyday social life does rest on trust. If you go to a restaurant, you’re served food before you pay: The owner trusts that you won’t bolt out the door after downing his cuisine. If someone in a police uniform indicates where you should drive your car, you follow the instruction: You trust that it’s a police officer, not someone who rented a uniform from a costume shop.

473

The economist Paul Seabright (2004) explains that the trust displayed by humans is unique in the animal kingdom. In other species, individuals exchange food only with others to whom they are genetically related. By contrast, humans exchange food and other value items with complete strangers. Grocery store workers hand you sacks of food; stores trust that your scribbled signature on a piece of paper will bring them money in exchange. You hand money over to bank tellers, trusting that they will keep it safe for you. Human societies have advanced through social systems that rest on trust.

Who showed trust in you recently?

The need to convey a sense of trust may have contributed to the evolution of emotional reactions. Smiles and laughter indicate that people are not a threat; genuine expressions of positive emotion indicate that people are cooperative individuals who can be trusted. Smiles and laughter, then, may have evolved to promote human cooperation and trust (Owren & Bachorowski, 2003).

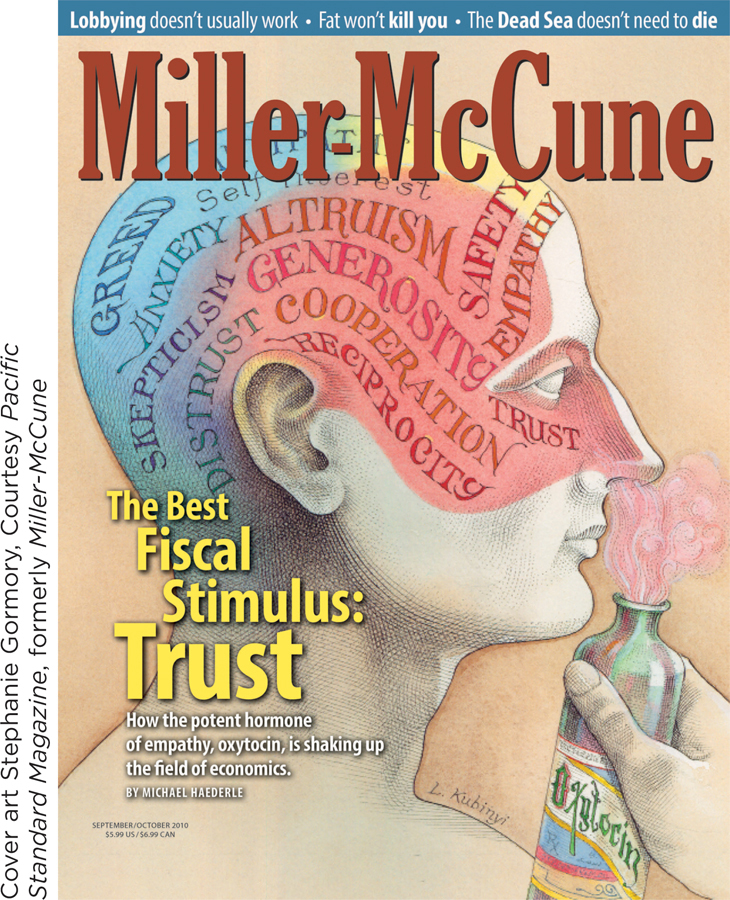

TRUST AND OXYTOCIN. Some research suggests that trust has a biochemical basis: oxytocin. Oxytocin is a hormone that is released into the body and the brain. One of its primary functions involves birth and the survival of children; oxytocin activates muscles necessary for childbirth and stimulates the release of milk for breastfeeding. In the brain, it may stimulate feelings of trust.

In research on oxytocin and trust (Kosfeld et al., 2005), participants played a game in which they were financial investors; they received money and, across a series of trials, chose how much to invest. To invest, they gave money to a second individual who had the power to decide, at a later point in time, how much money (the initial sum plus a portion of profit from investment) to return to the investor. The amount invested, then, revealed participants’ level of trust in the other person. Before the game, researchers manipulated oxytocin levels. Participants received a nasal spray containing (a) oxytocin or (b) a placebo (i.e., no oxytocin).

Results indicated that oxytocin increased trust. Investors who received the oxytocin spray invested more money (i.e., displayed more trust) than those receiving the placebo spray (Kosfeld et al., 2005). The effects were substantial; more than twice as many people in the oxytocin condition made the maximum investment; they fully trusted the other individual.

The results suggest that oxytocin is like a “switch” that flips on a biological system that generates feelings of trust and good will. If true, the implications are significant; they suggest that people’s behavior could be controlled—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 10

Humans’ willingness to exchange food and other goods with those who are not QcU1of6C/cJn1DC4Gu89Xg== related indicates a universal need for trust. Experimental research indicates that the hormone QvNtpIgET7d3fPXvh/n5qA== may stimulate feelings of trust.

474

THIS JUST IN

Oxytocin and Individual Differences

In the first decade of the twenty-

But when the results of this research came in, they weren’t quite what people had expected. Nearly half the studies exploring oxytocin’s effects on behaviors involving trust and helping showed no effect. More complex studies showed that oxytocin was influential in some settings but not others; for example, it increased trust toward people unless they appeared untrustworthy or were members of a threatening social group (Bartz et al., 2011). Why might oxytocin have variable effects on motivated behavior?

The key to answering this question is to rephrase it at a person level of analysis: Why do people react variably to oxytocin? This phrasing highlights a critical fact: People differ. They have different life experiences, skills, beliefs, and personal goals. They think differently about social situations and personal relationships. All these personal factors affect motivation. Thus, it is natural to expect that oxytocin (or any biochemical) might have different effects on different people in different situations.

One study shows that oxytocin’s effects vary among people with varying levels of social skill (Bartz, Zaki, Bolger et al., 2010). Researchers first measured social skills, specifically, the skill of understanding other people’s thoughts and feelings. Next, they showed participants a film in which an individual discussed emotional events. They then asked participants to estimate the person’s feelings and measured the accuracy of the estimates. Before the film, the researchers gave half the participants a dose of oxytocin and gave the other half a placebo. Oxytocin did not have a uniform effect. Instead, it increased accuracy among people with very low social skills, but not among others.

Another study examined the effects of oxytocin on adults’ recollections of their childhood interactions with their mothers. Rather than studying the average effects of oxytocin on people in general, the researchers explored an individual difference variable: people’s levels of anxiety about close personal relationships. Oxytocin had different effects on different types of people. Among people low in anxiety about relationships, oxytocin created more positive recollections; people remembered their mother as a caring individual to whom they felt close. But among people high in anxiety, oxytocin created less positive recollections; they remembered their mothers as less caring and close (Bartz, Zaki, Ochsner et al., 2010).

Thus, in both studies there was no single effect of oxytocin; it was not a “love hormone” that filled everyone with fond memories and a deep understanding of others. Oxytocin’s effects varied. The variability cautions us against presuming that any biochemical will affect all people in exactly the same way, all the time.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 11

Which of the following statements correctly describe exceptions to the rule that oxytocin increases trust and other positive social outcomes?

- LEk5tfAGCw6/JBZpuXQA7VWRhTgTfT/UbXFPNcDI3HeTsZf0NPPVoYyE9DwVSVfq9tzVv8bco3JJZklK/kgLBM0JKNnGRpetpaKxjEjZG5Y53efulVHF/GaVyuyyyWzPA/0yxohJ98ySvRljOCzCvX1ciTRHXQ0+FHJd39r7pE7HqdL26bIngFizyiAbqPymihdrmx2Mpr0=

- uZO19e16GDXDSMfJO9Bxqdd6/FFdXdMAarp8Xbja88Ox/b77lmd5Tq7A/+v7dLPNV/Faz6/ILgtQHOxcXYUn7vJ8P0qqXctClfaYqTJKO7YeC86YXjpHUMtIjubMr7WDpwtoMszaBjKpH/JX4TOdR0TyuXvbpCdyAv3tVgEzPnVurWx+2afoNwb+KBj0eXxgx9eYJAHU4uaCZwYYf0T4TD6m7YGE2Yin

- rvu5fFIaAsHM+tDtJm9YlpPXUSoxRAYZJZGSxtrEU4yGgFT4unppLG+WklGHgy8A28H2bcrzVaSkQpwDgKlqMSXsOybCNo1sLygkHTjyyfiXF3rELwc+Ob+lGoRba/IdBNYMzI8ByAFTQZkm6lbzeTrB4EvHaeyf0aV87I/h6G27KTccUF3LPmqgkK6ckvqRvBtQkZP62jkgTUEVTdFx8vUb024+zxqLnWtVhucd1fymNQWbZTWxw50kv63Ce5qNr3W5bg==

475

TRY THIS!

Before you start reading the next section of this chapter, which is about motivation and thinking processes, or cognition, do something else first: Complete this chapter’s Try This! activity. Motivate yourself to go to www.pmbpsychology.com and complete that activity for Chapter 11. ![]()