11.5 Cognition and Motivation

The motivational forces we’ve covered so far—

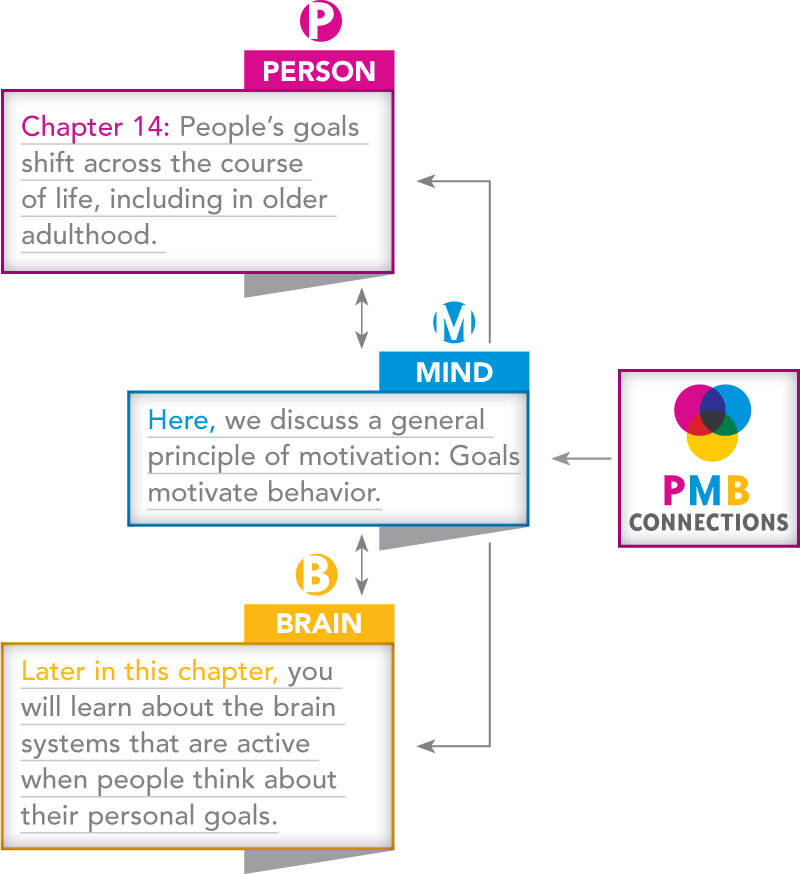

Things aren’t quite so bad, though. The factors that affect motivation include thinking. People’s thoughts about themselves and their activities can affect their motivation and success. This simple fact has major implications. Because thoughts are at least partly under your control, the influence of thinking on motivation gives you personal agency: the power to influence your own level of motivation, and thus your daily activities and the course of your life (Bandura, 2001).

Let’s look at different types of thoughts that affect motivation and thereby power personal agency. We begin with goals.

We have an added layer on top of the bird’s (and the ape’s and the dolphin’s) capacity to decide what to do next…. We can ask each other to do things, and we can ask ourselves to do things…. It is this kind of asking, which we can also direct to ourselves, that creates a special category of voluntary actions that sets us apart.

—Daniel Dennett (2003, p. 251)

Goals

Preview Questions

Question

What kinds of goals are most motivationally powerful?

What kinds of goals are most motivationally powerful?

How important is feedback in motivation?

How important is feedback in motivation?

What type of goals can impose organization on our lives?

What type of goals can impose organization on our lives?

Can features of the environment activate goals that affect our behavior without our awareness?

Can features of the environment activate goals that affect our behavior without our awareness?

“What do you want to do today?”

“I don’t know, what do you want to do today?”

“I’ve got nothing planned; whatever you want to do.”

These people aren’t likely to be doing much today. They lack goals. In the psychology of motivation, a goal is a mental representation of the aim of an activity (Kruglanski et al., 2002). Goals are key to motivation (Locke & Latham, 1990).

CONCRETE, CHALLENGING GOALS. Not all goals are effective. People often have goals that they never seem to get started on. You might hear people say, “I know smoking is bad for me, and one day I’m gonna quit!” or “Someday I’m going to start knocking off some of this extra weight.” And you might hear them say these same things month after month, year after year.

The problem with those goals is that they’re so vague. When is “one day”? Exactly what does it mean to merely “start knocking off some” weight? If you want to motivate yourself, set goals that are specific and challenging (Locke & Latham, 1990):

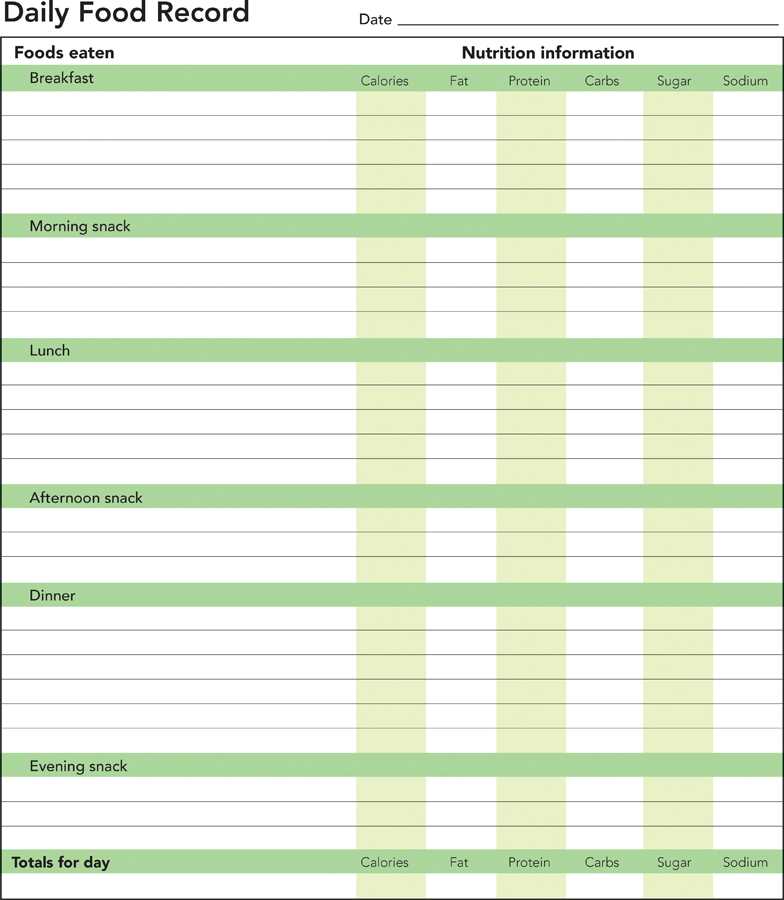

Specificity: Specific goals indicate exactly what you want to accomplish. For example, if you’re trying to lose weight (Franz et al., 2007), don’t aim for a vague goal such as “knocking off some weight.” Set a specific one, such as “lose 5 pounds this month” or “count calories and reduce them to 2100 a day.”

476

Challenge: If you want to motivate yourself, set goals that are challenging (while not being unrealistically difficult). People who set challenging goals (e.g., “I’m going to raise my GPA by 0.5 point this year”) generally outperform those who set easier goals (e.g., “I’m going to raise my GPA by 0.1 point this year”; Locke & Latham, 1990).

What are your goals for today? Are they sufficiently challenging? Specific rather than vague?

PROXIMAL GOALS. Compare these two people, both preparing for a marathon in six months: (1) “I’m going to run 600 miles during the next six months”; (2) “I’m going to run 25 miles a week during the next six months.” Both goals are specific. Both are challenging; in fact, they’re equally challenging, since 25 miles a week equals 100 miles a month equals 600 miles in six months. Yet if you want to keep yourself motivated, Goal #2 is better than Goal #1.

Compared to Goal #1, Goal #2 is a proximal goal, one that specifies what you should do in the near (“proximal”) future. Goal #1 is a distal goal; it specifies an achievement in the distant future. Distal goals can be discouraging. Before you get started, they seem so hard (“600 miles?!”). Once you do start, they still seem so far away (“I’ve been running for one week, and there’s 575 miles to go?!”). Proximal goals seem more manageable, and once you get started, there are markers of progress (“I did it—

A study with schoolchildren having trouble learning arithmetic illustrates the power of proximal goals (Bandura & Schunk, 1981). One group of children was given a distal goal: completing a 42-

Keep this result in mind when you have a long-

FEEDBACK. Setting goals is a first step in getting yourself motivated. To see the second step, compare these two situations:

You’ve got a final exam in two weeks, and your first aim in getting ready for it is to read 50 pages of your textbook.

477

You’ve got a paper due in two weeks, and your first aim in writing it is to come up with a good idea for a paper topic.

Now imagine that somebody asks, a few days later, how you are doing. For Situation #1, you can tell precisely; if you have read 20 pages, you know “I’m 40% of the way toward my goal.” For Situation #2, you can’t tell; if you have been thinking about the paper but do not have a good idea yet, you do not know if you’ll need five more minutes or five more days of thinking to come up with one.

In Situation #1 you have feedback: information indicating your progress toward a goal. In Situation #2, you lack feedback; you cannot tell exactly how much progress you have made. Situations with feedback are motivating. Situations without feedback can be frustrating and demotivating. Research manipulating feedback, as well as goals, shows this.

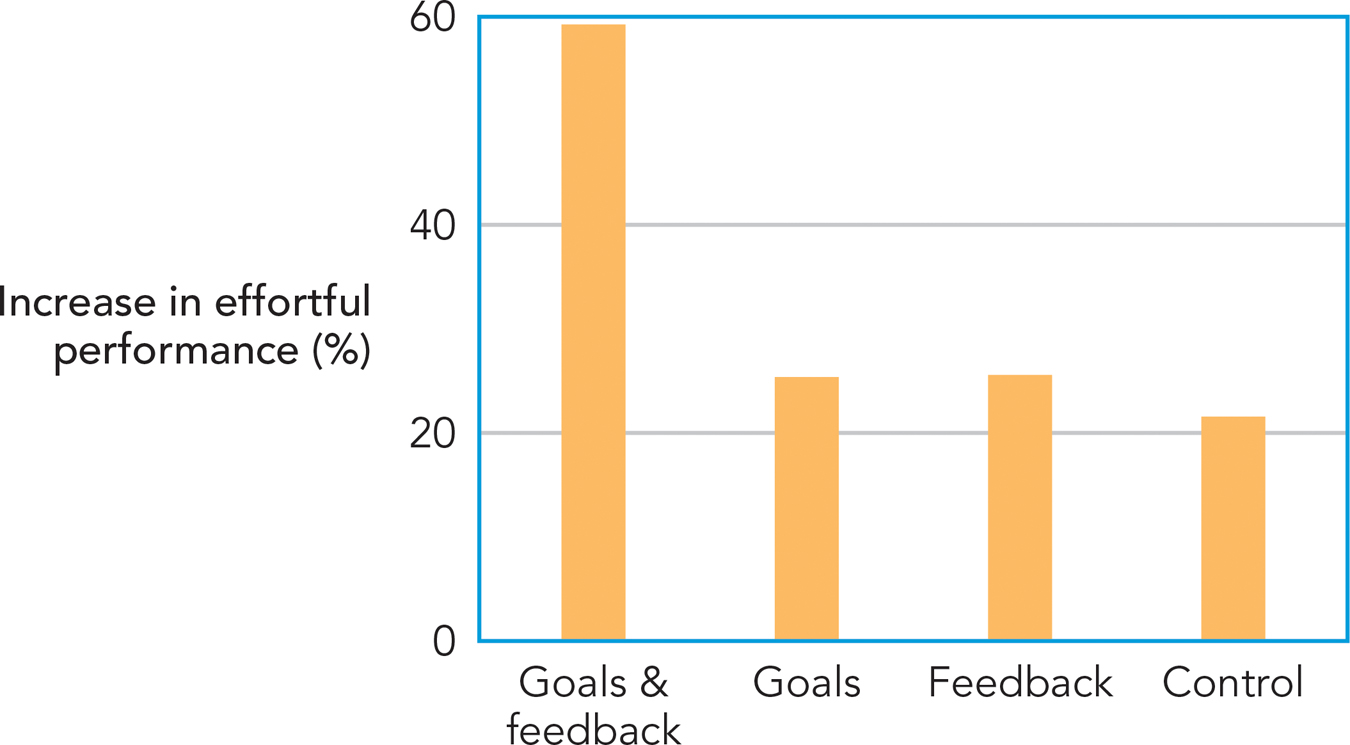

In this study (Bandura & Cervone, 1983), participants performed a tiring task: riding an exercise bike. Some participants were given the goal of reaching a specific high level of performance, whereas others were encouraged merely to do their best. In addition, half the participants received feedback showing their exact level of performance, whereas others did not. The only situation that was highly motivating was the combination of goals with feedback (Figure 11.4). The lesson? If you want to motivate people (including yourself), make sure that (1) the goals are clear and (2) people get feedback on how they are doing as they work toward achieving the goals.

This lesson may remind you of our opening story about Emmanuel Yeboah. He not only was deeply committed to his goal. He also (1) possessed a goal that was clear (he aimed not to “ride his bike a lot” but, specifically, to ride from one end of Ghana to the other) and (2) received feedback on his progress (he knew where he was during the trip, and thus was aware of his progress and the miles remaining before he reached his goal).

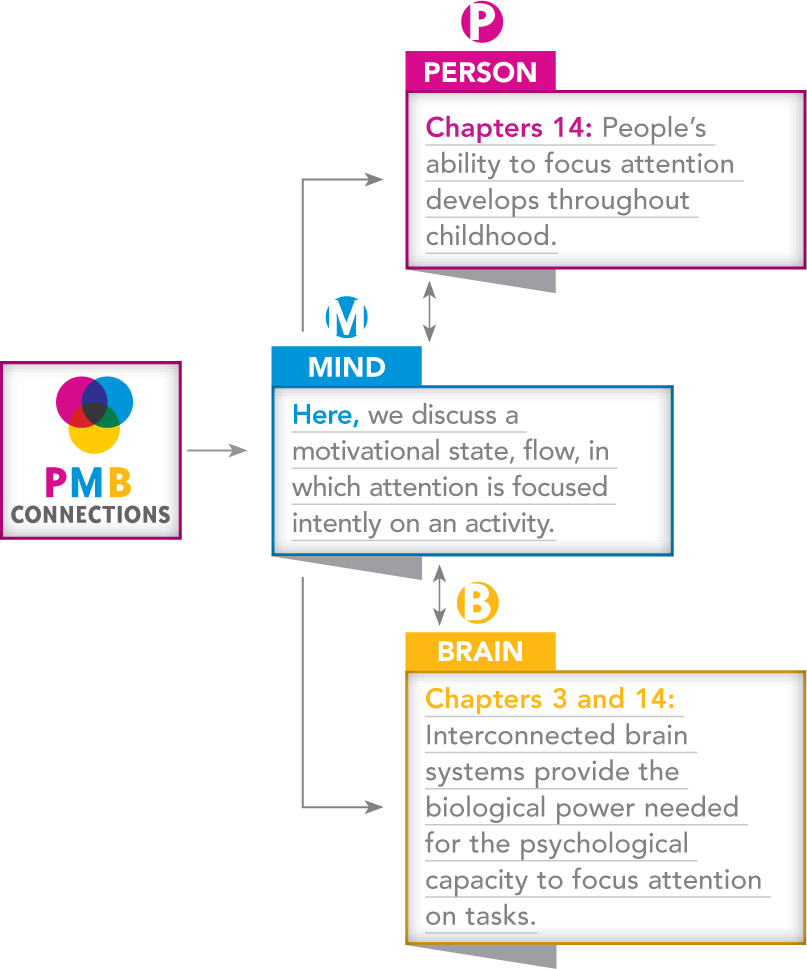

CONNECTING TO BRAIN SYSTEMS AND DEVELOPMENT

478

Why are goals and feedback so motivating? It is mostly because of how they affect people’s thinking (Bandura & Cervone, 1983, 1986). If feedback shows you are falling short of your goals, you may become angry with yourself and push yourself harder to succeed. If it shows that you are doing well, the feedback can boost your confidence, or perceived self-

479

PERSONAL PROJECTS. Some goals motivate behavior that involves one specific task. Consider these three goals:

Get myself to the gym tomorrow morning.

Bake a cake for Sue; it’s her birthday.

Memorize all the formulas before tomorrow’s chemistry exam.

Each goal can be fulfilled by performing one specific activity in the near future. Other goals, however, are broader in nature. Consider these three:

Get myself into shape before next summer.

Be a good friend.

Get into medical school.

This second list contains personal projects, which are goals with two defining qualities: Personal projects (1) incorporate a number of different actions with a common purpose that (2) extend over a significant period of time (Little, Salmela-

Personal projects help to organize life. Thanks to your personal projects, many of your daily activities are not disconnected behaviors, but meaningfully interconnected efforts to fulfill a long-

TRY THIS!

Personal projects should sound familiar to you from this chapter’s Try This! activity. The project assessments that you completed are essentially the same as those used in the psychology research you are reading about here.

People have more difficulty achieving their aims when different personal projects conflict with one another. Suppose that your goals include both “finding more time for studying” and “finding more time for exercise,” or both “making myself appear smart to others” and “being honest with others.” The incompatibility, or conflict, between the goals can create stress and interfere with their achievement (Emmons & King, 1988; Presseau et al. 2013).

Personal projects contribute to a human quality we mentioned earlier: personal agency (Bandura, 2001). People can motivate themselves and thereby influence their lives and personal development by setting, and remaining committed to, meaningful personal projects.

THINK ABOUT IT

Goals are important to motivation, but might there be more to the study of cognition and motivation than just goal setting? What about those times when you have the goal of doing something but somehow “never get around to it”? (You’ll read more about this later in the chapter.)

480

AUTOMATICALLY ACTIVATED GOALS. By setting goals, then, you can influence your behavior, “motivating yourself” into action. Goals thus give you more control over your behavior … sometimes.

Other times, goals give you less control. This happens when goals are activated automatically, that is, outside of your conscious awareness. Sometimes a subtle cue in the environment—

In one study (Bargh et al., 2001, Study 1), the subtle cues that activated goals automatically came from the words in a word-

One everyday stimulus that can activate goals automatically is advertising logos. For example, after being shown the logo of Apple, a company known for its creativity, people performed at higher levels on a creativity task (Fitzsimons, Chartrand, & Fitzsimons, 2008). After being shown the logo of Disney, a company that people associate with honesty, participants answered a self-

What goals are being potentially activated by the stimuli in your current environment?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

True or False?

- Ira1Er2usiBnHz3rwxXaqHAZd0tc0tNbL9muwxZdi1LJkJHdYm+Ag2ZUPo6kd9/K569JBgPWvVV3oD7q7AxW9RKi0rvHf+Egkgmsmmi6g5CZcTM3X3qxD5ycvO/rpqHUybBxjyXepN1jOnDe7CZy2LwOGmA1ybuSbdEB4iMsbB9RBt7ss46lNThgIaHYrk5FMr1X0dCcTWjpjsmW0dqE2Q0+zCHNkD7+2UKNzw==

- 1dDLP+mF9XfWwfCjcplaB7ErZel3AwiJf1gUhzPl0opVWJMSoq/+/CudyZub90159l8eNK0GdXog8YO9O2LtQkX1tyv9ErbY8lITMfqddGyHdToHRYPBADhoII0ML0xHzI/QdIep628dDNcZNdXGQPRh9Rt+dsiXIpmCYAyBRowJ/ufMASCvfjqBZpjYJKU6Q1EXqaYPKbQ0iF6xpTWkyUsZW5HcxH2epq+l9eV4aGaT+6JRrygr/hma1l4VamuG5aVD/Q==

- 5TbJNGAM72odp0RAwQRo7X9vqRhxOeDweV5vpiAWNiLT5xUZwaYLgVTJhO3BLENm0SJoWpg2zOIKYNYwqr6+umntSOAwqswck68fWsPZQJgiEhGsPtd5PHWZbM4+XCtyQCSQxdmJ4RGhhtMEZPmZ5WK4uE1Y+hHfUwFb66Mr/95YxA7r8jduTCK4iw6Ob36v14pka1GEdPdYeDoGAJCTRhJP9QE9HFAbYh344RWxe/h5Gh0lN2Pa/FLw5vjHhLggydKfxlOYwD3vtzs7epPhr0IO/mT2WKt/K7+F9LqXCWYBD995

- WjvcS30bfjL8B8M0BSHrRZKfjBC7+W5ErCYJeFim1u08Bi7EKr0I6mASQ+QhoWLNVzzjNte9XyotEZeGD3r/OLlR2uii8/5oEp3Jjv9BEEe0wtiUag9jSkDP7Dg1FhQbDdsvEM0pCnUPovFhSEBEEgg27NB/q0KqVIlG6VBwBbYgb9nIasRiEnxCTnO8yTNpSOnBMvGIOUHWA5Qy/XVA1BcKOBJ8xGrcscMInoZYbk30Pu9g+78/lQ==

- lHQAFxlhLINMea0iRPI+bqYYfmwS3oBCvtZYF5mXXgOnCtyBM4tviblPBSLcq/7jKEtyCoB7mNbIBdqiKO33DULZedcUheDJIq9OWWLSFmnIsN66hWGGWPh5L3rQty5AQdNWgKPRKUE7BaHh7SuBOKR3YPUy2PSw3x5RcDW9R5hv3rbpMQeRVSvuooCrbjyMp+Pbw9jiQZTlh8J4DnW+aA==

Implementation Intentions

Preview Question

Question

How detailed should we be in our goal setting?

How detailed should we be in our goal setting?

Goals enhance motivation. Sometimes, though, people set concrete goals yet fail to act. Your goal is to start working on a term paper, but a friend calls, you lose track of time, and never get around to it. Your goal is to pay a bill on time, but you start reading a book, forget about the bill, and remember only weeks later that you forgot to pay it. You know what you want to do, but it’s hard to get yourself to do it.

The psychologist Peter Gollwitzer and his colleagues have devised a method to help you achieve the goals you set: implementation intentions. Goals indicate what you want to achieve, whereas implementation intentions specify exactly when and where you will work on achieving those goals (Gollwitzer & Oettingen, 2013). The setting of implementation intentions, then, is another way in which thinking can contribute to motivation.

481

A study with college students on Christmas vacation shows how implementation intentions work. Prior to Christmas break, experimenters gave all participants in their study a goal: to write, and submit to the experimenters by the end of the day on December 26th, a report about how they spent Christmas Eve. They instructed half of these participants to form an implementation intention; specifically, these participants, before Christmas, wrote down when and where they would write the Christmas Eve report. The implementation intention helped students achieve their goal of writing the report on time. Three out of four participants with implementation intentions wrote the report, but two-

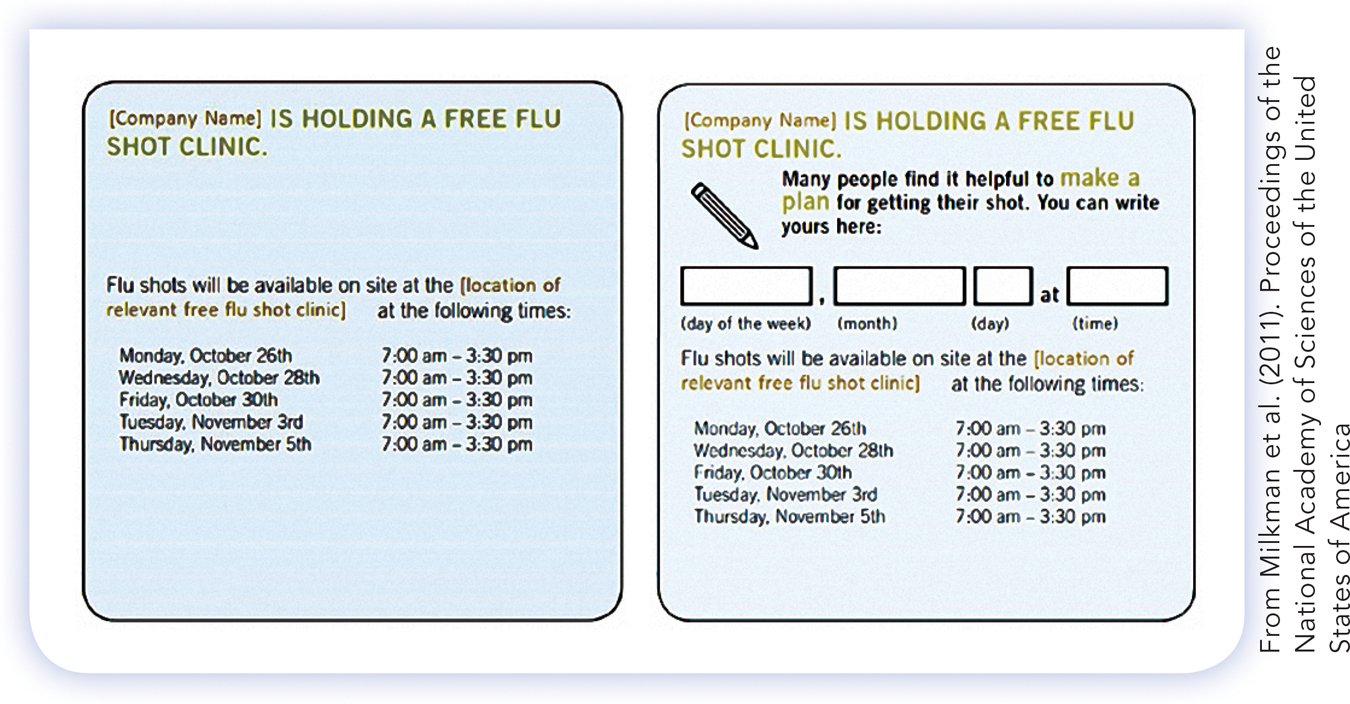

Many subsequent studies confirm that implementation intentions help people put their goals into action (Gollwitzer & Sheeran, 2006). For example, in a study of employees of a large company, researchers used implementation intentions to boost the number of employees receiving flu shots (Milkman et al., 2011). Some employees received a mailer listing times and locations at which free flu shots were available. Others received this same information plus an implementation intention: encouragement to write down an exact day and time at which they would get their shots (Figure 11.6). Implementation intentions worked; significantly more employees with implementation intentions got flu shots. In percentage terms, the effect was not large; flu-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 13

OoNMFd3XScKL93mL523jN+jT5uQLX9rM6CMRsfaTWQAB0WZYFN6sAgfj6GC/bhso5qAg8iY6SsG/qWvLqwabGKQfzHkejgVFU3dAibDfLIeI+3UV8VNhv6QKbRRgywAnLYPtrvMIxcLK9occ4r3AIongLHLz1deJdnrzocLuNdX4qunQ8eKCug==Making the Distant Future Motivating

Preview Question

Question

Can implementation intentions motivate you to save for retirement?

Can implementation intentions motivate you to save for retirement?

Implementation intentions are good when you need to accomplish a goal (e.g., start a paper assignment; get a flu shot) in the near future. What about goals in the distant future, such as having enough money for a comfortable retirement or being a healthy, physically fit older adult? Implementation intentions are not much help with distant goals. You can’t fill out a form indicating hundreds of specific occasions, over decades of time, when you will, for example, take steps to be more physically fit (“January 12, 2043, 8 a.m.: Jog 2 miles; January 13, 2043, 7 p.m.: Pass up dessert”). It’s not practical.

Distant goals pose one of the greatest challenges to motivation. Even when they are important, short-

Here’s the challenge: How can one make abstract, distant goals more motivating? Hal Hershfield and colleagues (2011) devised a clever strategy based on the following reasoning. Distant goals are not motivating because people do not relate strongly to their future self—

482

In different experimental conditions, participants looked at a digitized image of either (1) their present-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 14

Ar5CNKMEubzYVJ25K62wuEimTOJ75HxLEqmywAnPJZwiCULjLENstsydbk9n5kS1tFR25uin9ytPogPMsZlQ0l3Une2Kd3u8Ii59JnYESsMPk77lJKflIKA87mfyUAto6vNAQiZND5pmb66sHi81o65IH/socnB/6gKlW7W/neEjW6WsgqV9CHt/p8aFBrBd3EoJUHwdwMWCA+Jiyk9NMrhtgfiyPe4z3oBn+FVzVGpvR2A2fj45B7qVzvaBj9mPYAqWCeTL4bu/QPn3wU9IGv1IHKqX2Xk6CKVGj9qXMadYIkqhcpL5aS4YGI9WJPQOh7AgPE0G+pLwYWuv2j+VjvpxmucavJvxE6ITHGPx16UcVNTq8WW8agSxpdHbMLoRrGnMki2Xm+6Y/42/WBLHpBmj9oUe9Ddc3d1wQLCClek9HSfPru8GbELgZv+lDq4VGuzzbCL9BJMT6rnRAKXmTXTMnNzZ4FlP1hFocD8hNhnvKXyi4iTLur8L4+woTZD0Cw8oKnyt+Qx+LOQ2JgnKRTRnj5lZzMUByndKgAKUmFE=Motivational Orientations

Preview Questions

Question

Can your belief in your own capacity for growth influence motivation?

Can your belief in your own capacity for growth influence motivation?

Why does motivation decrease when we receive external rewards for activities we enjoy?

Why does motivation decrease when we receive external rewards for activities we enjoy?

When working toward a goal, should you focus on strategies that can help you achieve your goal or strategies that can help you avoid failure?

When working toward a goal, should you focus on strategies that can help you achieve your goal or strategies that can help you avoid failure?

How can you achieve a “flow” state?

How can you achieve a “flow” state?

Goals and implementation intentions, reviewed above, are thinking processes that can increase your motivation and performance on specific tasks. Psychologists also have identified motivational orientations, which are broad patterns of thoughts and feelings that can affect people’s behavior across a wide variety of tasks. Let’s begin our look at motivational orientations with the type of thoughts known as mindsets.

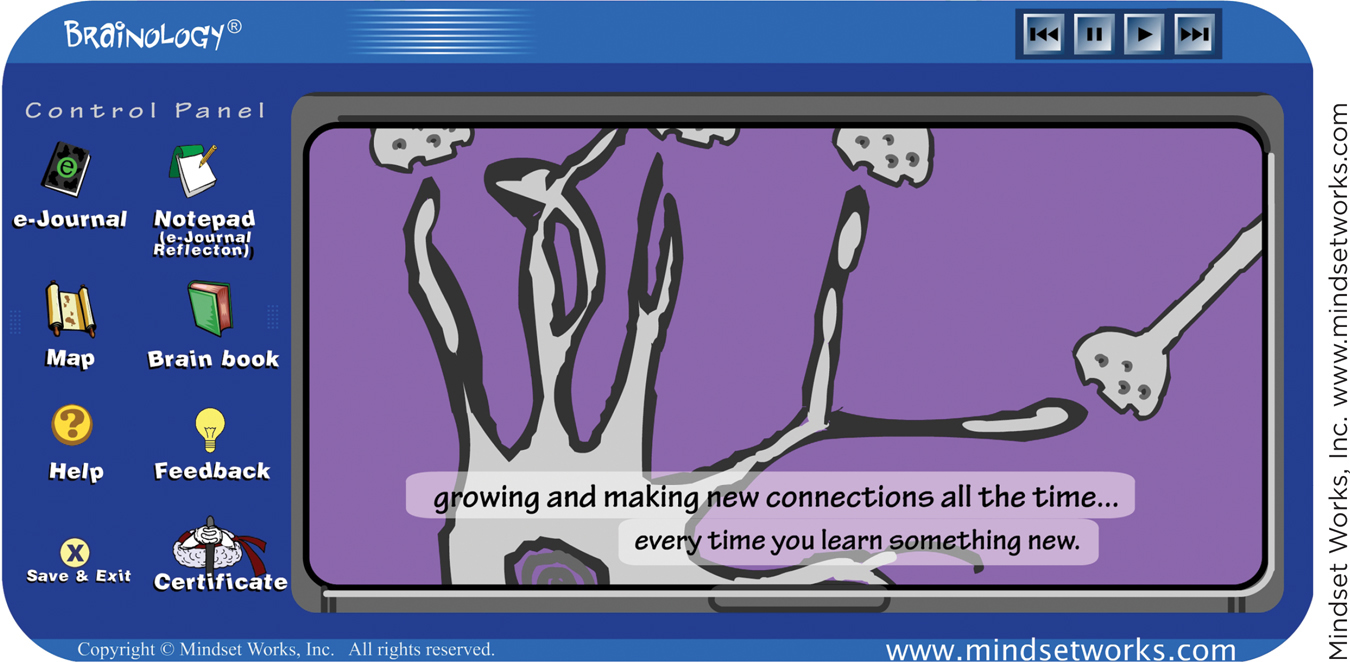

MINDSETS. The psychologist Carol Dweck has identified a motivation orientation she calls mindsets. A mindset is a belief about the nature of psychological attributes, such as intelligence. People’s mindsets differ. Some people believe, for example, that their level of intelligence is fixed; they’ve either “got it” or not. Such people are said to have a fixed mindset. Others believe that intelligence can change; it grows over time, as new experiences convey new skills. Such people have a growth mindset (Dweck, 2006).

What kind of mindset do you possess: growth or fixed?

Mindsets shape people’s interpretations of how they’re doing. Suppose you try a new activity—

483

Dweck and colleagues have shown that people’s mindsets can be changed. They enrolled a group of seventh-

INTRINSIC MOTIVATION. People often are motivated by factors and forces outside of themselves: a parent’s rules, a teacher’s grades, a company’s salary. But sometimes people are motivated by factors inside themselves. Intrinsic motivation is the desire to engage in activities because they are personally interesting, challenging, and enjoyable (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

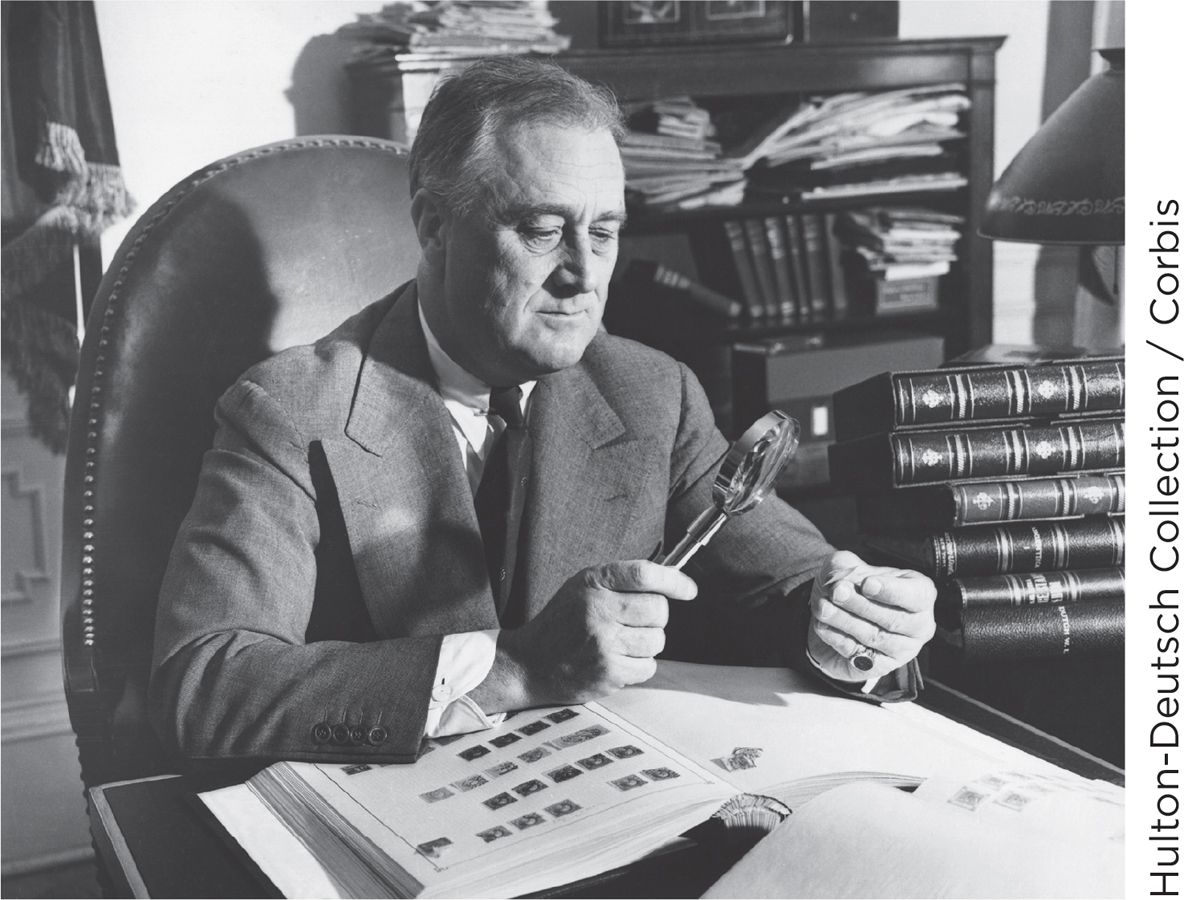

One aspect of life that highlights the power of intrinsic motivation is hobbies. If you take up a hobby—

A unique feature of intrinsic motivation is that rewards from others can decrease, rather than increase, motivation. In classic research, researchers studied a group of children who were interested in drawing, in other words, who were intrinsically motivated to draw (Lepper, Greene, & Nisbett, 1973; see Chapter 7). The researchers gave some of these children a reward for drawing: a gold star. As a motivator, the gold star backfired in the long run; it reduced the children’s intrinsic motivation. When they had some free time, children who had received the gold star were less motivated to engage in drawing.

In subsequent years, additional research examined the effects of external rewards on intrinsically motivated behavior. Results confirmed the original findings. A meta-

Why do rewards lower intrinsic motivation? One reason is that they reduce people’s sense of autonomy, that is, the sense that one is personally in charge of one’s own behaviors, which are consistent with one’s own personal values and interests (Ryan & Deci, 2000). If you choose an activity yourself (e.g., learning to play the guitar), the personal choice increases your feeling of autonomy, and the activity seems interesting. If somebody gives you a reward to engage in an activity (e.g., offers to pay you to learn the guitar), the external reward reduces your sense of personal autonomy, and you have less intrinsic motivation.

484

Theorists have viewed autonomy as a universal need (Ryan & Deci, 2000), in other words, one experienced in the same manner by people everywhere in the world. Although research conducted with people from Western cultures (North America, Western Europe) supports this view, research with people from other parts of the world suggests that cultures may differ (see Cultural Opportunities).

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Choice and Motivation

A basic principle of motivation research is that personal choice increases people’s motivation. People don’t like being told what to do; they like autonomy, that is, having a choice. When people don’t have a choice—

Does this principle describe the psychological makeup of all people? In one effort to find out, Asian American children either chose an activity to perform or worked on one chosen by their mothers. Later, when given another opportunity to try the activity, Asian American children, contrary to the principle above, were less motivated if they had chosen the activity themselves than if their mothers had made the choice (Iyengar & Lepper, 1999).

Other research has yielded similar results. In a study by Savani, Markus, and Conner (2008, Study 5), people in the United States and India participated in research in exchange for a small gift: a new pen. Half the participants could choose one pen from a group of five. The other half were shown five pens and then the experimenter chose one for them. Among Americans, choice increased liking; people liked the pen they received more if they had chosen it themselves. Among Indians, choice had no effect; they liked the pen just as much if the experimenter had chosen it for them. Other findings show that people in American cultural contexts are more likely to think about their own actions in terms of personal choices than are people in Indian cultural contexts (Savani et al., 2010).

Why do the cultures differ? Differences in motivation reflect deep differences in cultural backgrounds (Tripathi, 2014). Indian culture is steeped in Hindu philosophy that highlights people’s moral duty to fulfill obligations to others and act in a manner consistent with one’s social role. American culture, by comparison, is grounded in Western European principles of individual rights, liberty, and the pursuit of personal happiness. People who grow up in the different cultures develop different views about personal choice, and thus different motivational tendencies.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 15

HjLmoP5AB5xfd0/VUVkblTdXVHXjpJKTiDf4fsAiLMmi4C9kTe0uCFkQfYlZzpIss4cS85k92ocpvPAzai1pRXpdvCvmF0QyYr+k1xLThAfFMcnABXDlU8R0B1jcHpEwldy2lesktYytXqOKUPWyuzotX3GJfpgX5C7BnIWquEgdpp+ePROMOTION, PREVENTION, AND REGULATORY FIT. If you walk around a college library during final exam week, you will see a lot of people studying. If you ask them why they are studying, they might all say much the same thing: to do well on finals. But if you probe a little deeper, you will find differences. One person might respond, “I’m studying because it’s important to reaching my long-

Promotion focus: In a promotion focus, the mind is focused on accomplishments that one personally hopes to attain. People think about accomplishments they can reach (or potentially miss out on) when engaged in a task. The mind is centered on outcomes that promote their personal growth.

485

Prevention focus: In a prevention focus, the mind is focused on responsibilities and obligations. People think about obligations they may live up to (or fail to live up to) when doing the task. This is called a prevention focus because people’s minds are centered on threats (in the example, failing to live up to obligations) they hope to prevent.

Note that motivational orientations can differ even among people taking part in exactly the same activity. The motivational orientation does not describe what people are doing. It describes the way people think about what they are doing.

How do motivational orientations relate to behavior? They do so through a principle known as regulatory fit. Regulatory fit is the match between a motivational orientation and a behavioral strategy (Higgins, 2005), that is, a behavior means for reaching a goal. Just as there are different motivational orientations, there are different behavioral strategies. Sometimes strategies and motivational orientations go together psychologically: They “fit” together, like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle (Figure 11.8). When this happens—

In one study, researchers experimentally manipulated prevention versus promotion focus through an essay task (Freitas & Higgins, 2002). Some participants wrote essays about their personal hopes and aspirations, which created a promotion focus in those participants. Others wrote about their duties and obligations in life. This created a prevention focus. Afterwards, everyone evaluated different strategies for earning a high GPA in college. Some strategies were accomplishments one could attain (e.g., Complete schoolwork promptly). Others were negative outcomes to avoid (e.g., Stop procrastinating). Which strategies did the students like more? It depended on their motivational orientation. When promotion-

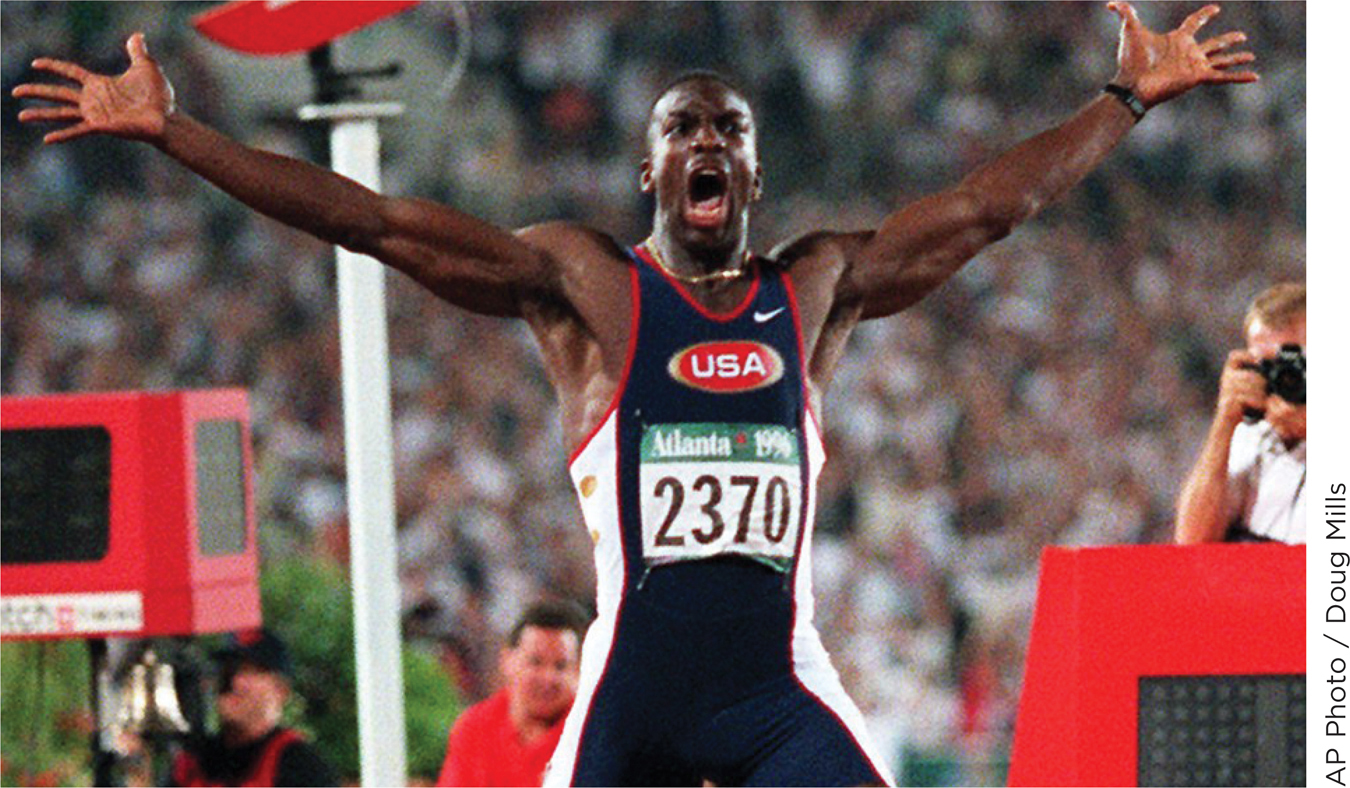

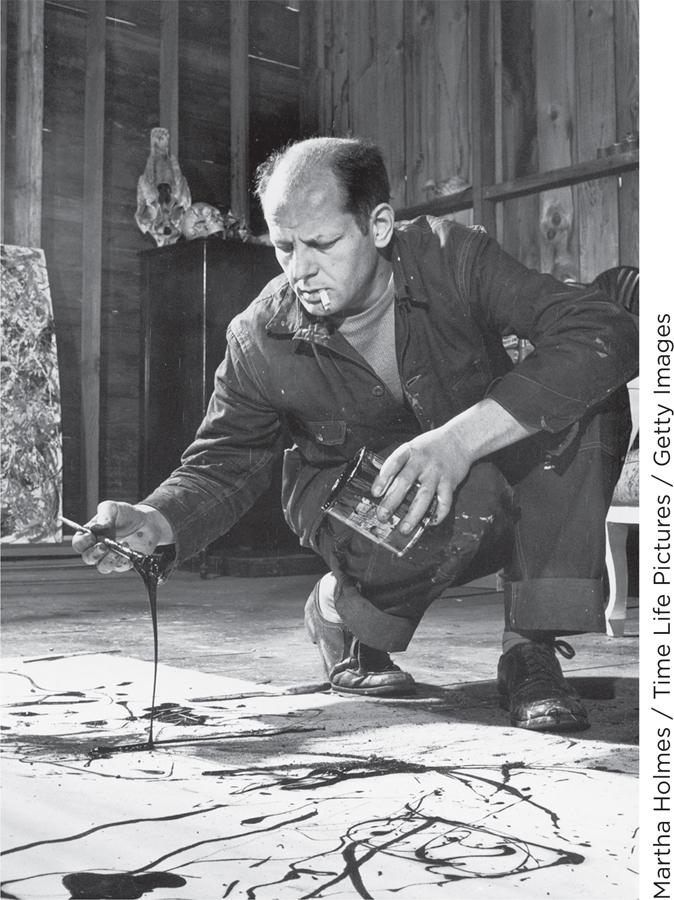

FLOW STATES. A fourth motivational orientation has been given the name flow by the psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (1990). (In case you were wondering what sound to make when seeing those letters, his last name is pronounced roughly chick-

My thoughts are very positive…. The moment starts to become the moment for me. Once you get in the moment you know you’re there. Things start to move slowly…. I let the time tick. I felt like I had the court right where I wanted to.

—Michael Jordan, describing his final seconds of play for the Chicago Bulls (as quoted by NBA Entertainment, 1999)

Flow experiences are distinctive states of consciousness (Weber et al., 2009; see Chapter 9). In flow states, there is intense concentration. Events seem ordered, meaningful, and controllable. Activities may appear to unfold more slowly than normal. People experience a pleasurable, powerful sense of control during flow states.

On what tasks have you experienced a flow state?

One group of people who you may hear describing flow states is athletes. Successful competitors may say they were “in the zone”: an altered state of concentration in which the game seems easy. Its flow of activity, fast and frantic for most people, is slow and calm for the athlete “in the zone”—or, in Csikszentmihalyi’s terms, in a flow state.

486

CONNECTING TO CHILD DEVELOPMENT AND THE BRAIN

There is nothing unique about athletics. A wide variety of activities can produce states of flow. The two key ingredients for creating flow states are the presence of (1) challenges that do not exceed people’s skills, and (2) clear task goals and feedback (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990). Any activity with these ingredients can provide a sense of flow. People may have flow experiences while, for example, playing a musical instrument, working on a craft or hobby, playing chess, or painting. Even video games can produce flow experiences when they provide challenges that match players’ skills (Hsu & Lu, 2004).

Researchers study flow experiences by measuring the quality of people’s experiences. They do so at multiple times a day, while people engage in a variety of everyday activities (see Research Toolkit). This enables the researcher to determine whether certain types of activities are more likely to produce flow experiences. In one study (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, 1989), a diverse group of more than 100 adults reported on their activities and experiences multiple times a day for a week. Specifically, they reported three key pieces of information: (a) whether their current activity was challenging and appropriate to their skills; (b) what they were doing (working, socializing, eating, etc.), and (c) whether they were experiencing psychological flow and its accompanying feelings of alertness, motivation, and happiness.

As predicted, participants reported more flow experiences when they were doing something challenging and had skills to meet the challenges. When there were no challenges, they were bored (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, 1989). Surprisingly, however, high-

487

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Match the motivational orientation on the left with the quotation that best characterizes it on the right.

Question 16

0TVAD45/2Jk0YLaOhnmDJzawVuxTNz7McYpFmJda56J2m97QsbOyEvl6GcTux8ihdfaiQfuD1zCDPKP0KjxiZmKngb8b+383HIId4LR+wZrFgiJUCK8bBplTfsOQ1XmP9MZQhkgxecZLiYUXuNyGqJG1Pt6oGVAdB1N2G3G+kkL7BENH56XcMQTw+SeKJr0rn2bferMsElTzflJ7z1pWrLWno/5ShS8aBkXUHTBcHGJyja2mh+IEURC87/I2yozRa43riRe5ga/nFDER94047T4NVkpWvWc8IX1B1LGkRBePCz6QBl5Qcr8CubIu7FxGJUV8JJusbP6UDrdrd7NTxTLOIMEcPi9+4O2Xffs2B4C4w1lANS8btSGmLjnIIod+DmCjtpi1q/hdr6pQt3QsDR6ahISJm474zh/go7mMrVHSuu9Uw3LfBD6D00Js90UTv7oWJq3ZPJL4g2FFrCE/k2T/GB6qPYDRGuHMLTYcDmjpBciDAhsHVeslgSStJxXCdzVrBOC2dbPU+BMmFzfW4/zzojO8tE17IBH5mG8/To/1V1oRyEM6LdjAfQeOIBhzryYTlG0pEZE7dZUVW3iGnei0OuLJaigkB0y2PcpKnVlI+KfMCVTGu/IqxuqrxJMArDi8QL46T+00AS01rMJ+J8Kg0slcvgcznUuZuxU4MaLUMrWRLXI8nZEsDx/TLNGc3ESumN/H8wVsli5DZw/Qz5jCOiJNPn3EVJh+LzUWXPZyRiBLoADIhoBYERJR4bHsF22Vu60gXQEkZ7ltpcz+yWJZ5xdQAv6iULSAJBihviKvFmNEfeLZxvY92/gn0EhKRESEARCH TOOLKIT

Experience Sampling Methods

Psychologists often study motivation in the lab. There, they can manipulate variables experimentally to determine their impact on motivation. However, psychologists aren’t fundamentally interested in motivation in laboratories. They want to know about motivation in everyday life. They thus need a research tool to measure experiences of motivation—

A problem is that there are so many activities. People do lots of different things, one after another, all day long, day after day. How could you measure all that?

In principle, researchers might videotape everything that people do over the course of a few days, assess motivation-

What’s the solution? Hint: You read about a similar problem back in Chapter 2. Its solution is relevant here. That problem occurred in survey research. Survey researchers are interested in populations that are so big (e.g., all voters) that it is infeasible to get information from all of them. The solution is to obtain a random sample: a subset of the population that resembles the population as a whole.

488

Motivation researchers use a similar strategy. Rather than trying to get information about every motivation-

The experience sampling method is a research procedure in which participants carry an electronic device (e.g., a pager or a smartphone) throughout the course of a study (which might run for one or more weeks). The device signals the participant to respond at random intervals during the day. When signaled, participants report on motivational variables occurring at the time they are signaled. For example, in a study described in the main text (Csikszentmihalyi & LeFevre, 1989), when participants were beeped they reported (1) the activity in which they were engaged, (2) whether it was challenging, and (3) whether they were experiencing psychological flow.

Experience sampling methods solve three problems (two were noted above). (1) They tap motivation in everyday life, not the lab. (2) They yield a useful amount of information—

Contemporary technological advances expand the range of data that can be sampled by researchers, as well as the ease with which those data can be collected. A major advance is wearable technology (Doherty, Lemieux, & Canally, 2014). Research participants may wear watches, wristbands, or “smart clothes” containing electronic sensors. These devices can monitor variables such as physiological state (e.g., heart rate) and participants’ location (using GPS technology). By combining these measures with traditional self-

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 17

Which of the following describe advantages of experience sampling methods?

- ZoeDBvEDNKYWtuRxq6JyxC1lARQmjyOGoNfJDhcbGJZdE2TYcNPnB3Hfi4lnRmMheXBg5ArJo/a4F8W2Hvq/y6eFHZ2KsI1/OTFhbBgazDL/dOKJbR0FKGv7VmIK62HzrKoJgDgzMTss06exf+MRTrIjklk=

- SbT2bBxcT+bgngz4KX2xGT2l9a1IWlH1VED+lSVz3QtZSCxWCvDCuPO74m4nhTsDpqnDbjHtkFDaLDWjxWo7LQ5OyZoCgVH2Yy83m+Di1vSFD+ED1Rl15wD4Amc=

- 1iKwT8a7pWBYtu6j4Jj1K878YNnvZGiTsuMlMqRuaYd2+XZ3+5pR8VU47fYHoKPjKHYrJpdVlp+MZfXR87kdtYWU6WCihVkoHtgBBCdOa0pbhXcLZFZtxBTmOOpv3cBXtFpV5I88x/QcUKQ8I3RRmPJbfoB49aDye2s3UB/BIXuX/InJmFt+2g==

- jPvfzgSr3rGGWWax3TlZGlq1akodLjZUNKPS5DoJUJaeONtgqGDU0D6Qmic2mnhFfIYGw1aJ1PmLX51EsU/QqEhaaIK/ztKI5PzpJIxCoNZXc84pN3zYrdxk8r7dabfaHpoqAlzn3tgC7141puegTW2ysW2qiJoCCXZgUe/WbLuAtlXAebVnw+cHgVGazJ9LZ6OLbwaj4GIIXznmAw+ycJOGX4zUWfWn