12.2 Social Cognition

We spend a lot of our time doing things with other people. But we spend even more of our time thinking about other people. “Why did my brother sound so weird on the phone when he told me about his new girlfriend?” “Is my new friend from psych class a real friend, or does she just want somebody to help her with her homework?” “How embarrassing that I forgot my professor’s name—

Social psychologists call these thoughts social cognition. Social cognition refers to people’s beliefs, opinions, and feelings about the individuals and groups with whom they interact socially. Three main topics in the study of social cognition are attributions, attitudes, and stereotypes.

CONNECTING TO THE SOCIAL PERCEPTION OF FACES AND EMOTIONAL STATES

Attributions

Preview Question

Question

How good are we at figuring out the causes of others’ behavior?

How good are we at figuring out the causes of others’ behavior?

In everyday life, we often ask why: Why aren’t my grades higher? Why are people saying no when I ask them out? Your answers to such questions are called attributions. An attribution is a belief about the causes of a social behavior.

Attributions are important in two ways. First, they affect motivation and emotion. For example, students who attribute school difficulties to a lack of ability rather than to a lack of effort become less motivated (Weiner, 1985). Teenagers who attribute personal problems to causes that cannot be changed, rather than to changeable ones, tend to become depressed (Hankin, Abramson, & Siler, 2001). Second, accurate attributions—

525

PERSONAL VERSUS SITUATIONAL CAUSES. When we try to figure out the causes of someone’s behavior, two types of causes stand out: personal and situational. If a friend says, “I am struggling in calculus; I might not pass,” the cause could be:

Personal: Perhaps he lacks math ability, or has not exerted enough effort.

Situational: Maybe the course (the situation he is in) is extremely difficult.

What determines whether we make personal or situational attributions? According to an attribution theory developed by Harold Kelley (1967; Kelley & Michela, 1980), the key factor is the degree to which potential causes covary with the behavior to be explained—

Your friend struggles in many courses, and most other students in the calculus class find it easy. The behavior covaries with personal factors (qualities of your friend), so you make a personal attribution; for example, you conclude that your friend isn’t very good at math.

Most people are struggling in calculus—

even students who find other courses easy. Here, the behavior (struggling in courses) covaries with a situational factor (the calculus class), so you make a situational attribution; for example, you conclude that calculus is difficult.

THE FUNDAMENTAL ATTRIBUTION ERROR. Thus far, attributions seem simple, so you might expect people to be very good at attributional reasoning. But it turns out that people commonly commit an error—

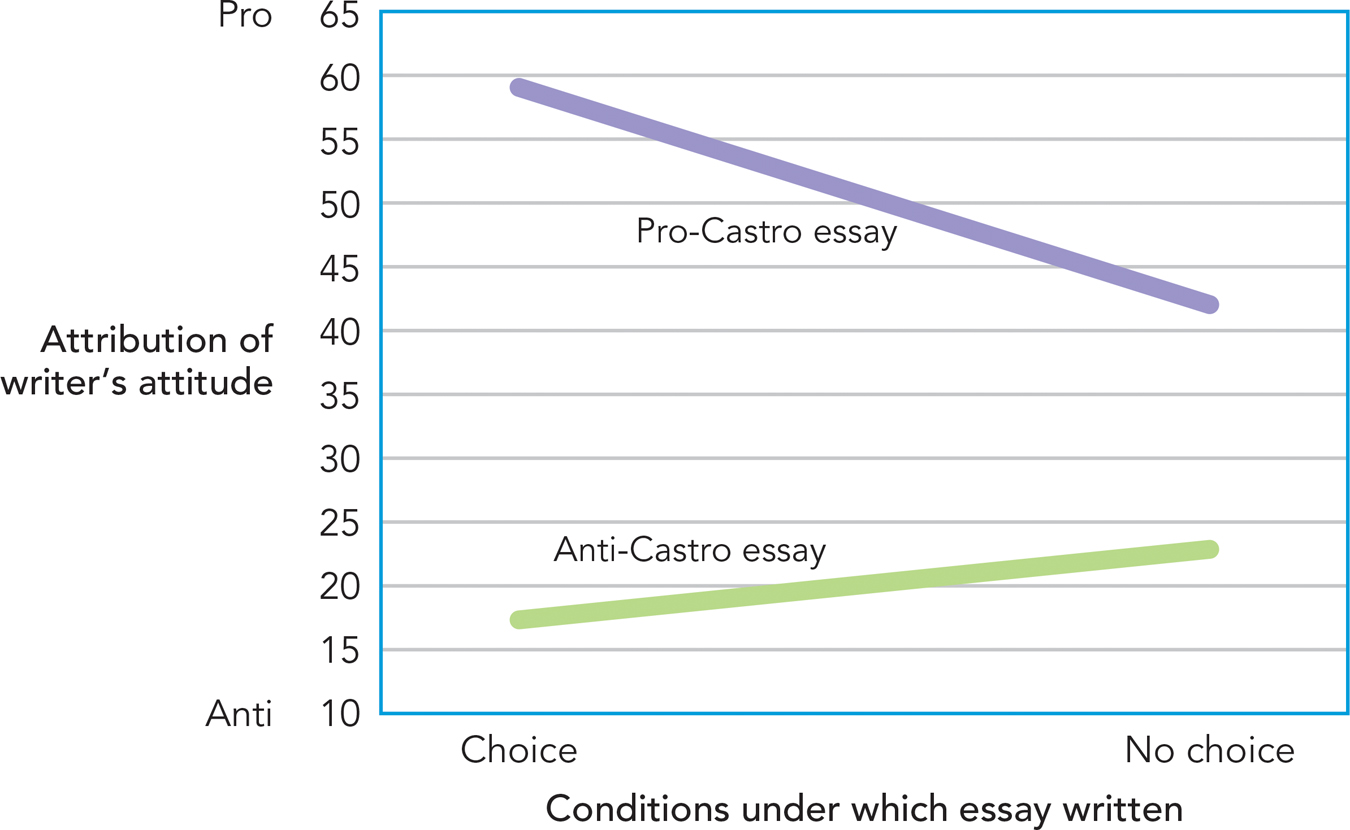

The fundamental attribution error is evident in a study in which participants made attributions about the causes—

Imagine yourself in this experiment. In the choice condition, the task is easy: The writer chose the essay content, so it must match his true opinion of Castro. In the no-

Now look at the results (Figure 12.4). In the choice conditions, when the essay said good (or bad) things about Castro, participants of course judged that the writer’s true opinion about Castro was positive (or negative). The surprising result occurred in the no-

526

In another fundamental attribution error study, participants played a quiz game in which pairs of participants were randomly assigned to the role of questioner or answerer (Ross, Amabile, & Steinmetz, 1977). The questioner role was relatively easy: devising quiz questions on a topic of one’s own choosing. The answerer role was difficult: trying to answer the questions devised by the questioner. After playing the game, both the questioner and answerer rated their own “general knowledge” and that of the other participant. A third person, who simply watched the quiz, also rated their general knowledge.

On logical grounds, there is no reason to think one participant was more knowledgeable, in general, than the other. Even if the answerer had trouble answering questions correctly, this doesn’t mean the questioner was smarter. Participants were assigned to these roles randomly. If questioners had been answerers instead, maybe they wouldn’t have looked so smart. Yet when people made their ratings after the quiz game, the winner was the fundamental attribution error: Contestants and observers of the game made personal attributions, judging that the questioner was more knowledgeable than the answerer.

Can you think of a time when someone attributed your behavior to personal factors when it could have been explained by situational factors?

In summary, when considering the causes of others’ behavior, people often overestimate the influence of stable personal qualities (e.g., attitudes, personality, intelligence) and under-

THIS JUST IN

Attributions—Causes or Reasons?

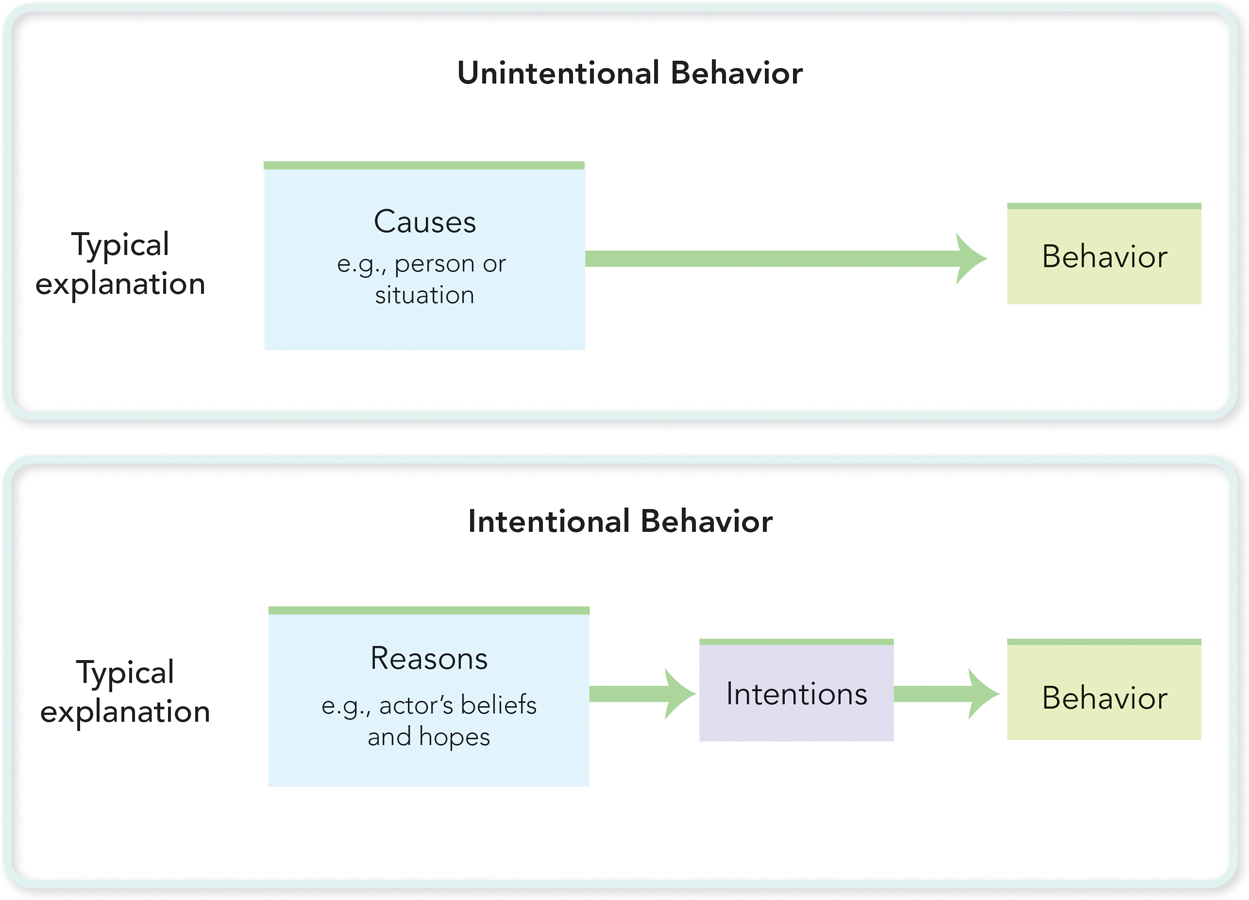

In the social cognition research you just read about, researchers tried to determine whether people attribute behavior to personal or situational causes. Social psychologist Bertram Malle (2011) has raised a different question: When explaining behavior, do people always cite causes?

Consider the following examples:

Example 1: On a wintry day, someone slips on ice and falls. The person explains her behavior this way: “The ice caused me to slip and fall.”

Example 2: In a comedy skit, a clown winds up to throw a pie at someone, but slips and falls, landing facedown on the pie. The clown explains her behavior this way: “When planning my comedy routine, I reasoned that it would be funnier to slip and fall on the pie than throw it.”

527

The examples differ in two ways:

Whether the behavior was accidental or intentional. Falling on the ice was an accident. Falling on the pie was intentional.

Whether the explanation cited a cause of behavior or a reason for behavior. The slippery ice was a cause. But the desire to be funny was the reason for the clown’s planned fall.

Causes differ from reasons. When mentioning a cause, the person could be wrong; maybe she slipped on a banana peel she didn’t notice, not a piece of ice. But when explaining a personal reason for action, the speaker normally can’t be wrong. The clown knows, absolutely for sure, that the reason she fell is because she planned it, thinking her fall would be funny.

People tend to explain unintentional behavior in terms of causes: factors that directly produce the behavior. However, they commonly explain intentional actions—

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 7

For the two descriptions below, determine whether the given attribution is best characterized as a reason or a cause.

- 1/JlyabbSAa8do21xEwAYXkVwPm4lsYFlT9pHJufHQUFdId51MOVyussJ2iH541CjApAvqeoptQsmz5FXz90+3zb5NrxnaBMShAop6CiPq3nt9qGYcPhljfpvKcCo45q

- C3sZXQytVithzS9MZ9cn35MRNRzdI6890ctVVqJLb5TQB354FnozKj4ZGHmfMDfPIMcYNAyGTh5Y0pLbUKDyogJo1d/ZwS8dOQtPgQDrLAN+5YPfyvtS6r4bt8nFcZpQUzCDZSSYPtbUCl+7a7+KMZa7l78yUn2/VdL1DmaS8/++lkZNzh4Dege3lOq+qYsXU/vvPFRM3KM/9Qt8nUftxNAjExSaZXcgB2tM3vUYdNCSJ8KoVxcBGNpWiJaLATXnZR6twpKCMX189tA/I8m3y0M8+do=

a. This attribution is best characterized as a cause because Mia is citing a cause for a behavior that was unintentional. b. This attribution is best characterized as a reason because Ron describes a planned strategic behavior he engaged in, and his explanation was story-like.

Attributions, as you have seen, involve thinking (about causes of behavior). In a second aspect of social cognition, thoughts combine with feelings to form social attitudes.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 8

pPvLNdN7zhpRNPtTvGhTbQQaysDzRxZuQLqEJ+jvmCqjkX596/gYtU9CSxvZ4yoRMxOJUPxa1xYqIpTPoaJ5+YDWjyOuNcsVoYtgtFSlTT3F1ieRxkvjWfe4JcuUwWxmsKjUn3jJOd7KKEnxuMNtNb2MVuA17fHv3MozRWsiPAW/UH2XV0wLMIteFANg7UEBxvclHCdTdOOkiHcRmtIpt52Ol9Z4AYnYmzp9f63leoX454v5yO4bIgGZp3eK98NM5G0WOJBjMHX78CkHwqOzFsa3dErEoUPpVpR6ylFkLk3/or4wf34V3VP3mAVraXacUKSmsyARpoazIbV+qNuMMvy3IP09kNw3+4tIof2POWe8xeWaZAqD1gP4LGZQgvNImD9txMxdt1lOElA7rGZpK88dwkQ=Question 9

Y0E+YrjFT3/Spwls7FPYePfYssxHQJ+ECMFf6CznlZCRcjopwj6YuwFTynSZB9loSLo7rOsJiNIUfGZWM/453WFgCR5yQL4UUpXc2GSzUhA2nbBJjZkiCRh5dbUfvApy520MghukWH0OSFw8j4Q1k4vaumjflrKuJBAhFiDpnoT7P0lB/JTOYtKeT647EaVF12bjqioZXt7++5wxxi9Y+fw+uN6RvmtfmQgTQh88Gtw61/XgYgwYlxT8CKS1uRqDhfetmA==Attitudes

Preview Questions

Question

Are strong arguments always more persuasive?

Are strong arguments always more persuasive?

When do our behaviors change our attitudes?

When do our behaviors change our attitudes?

When do our attitudes predict our behavior?

When do our attitudes predict our behavior?

528

A quick question: If you’re the average American, what feature of our society did you encounter about 40,000 times a year while growing up (Comstock & Paik, 1991)?

If there’s a television nearby while you’re reading this, you’ve got a big hint: It’s TV commercials. Businesses spend billions of dollars a year on the tens of thousands of advertisements that you see on TV—

In the long run, they’re trying to get you to buy their products. Yet, many ads don’t actually say, “Buy our products!” They’re more subtle. Advertisers present their product alongside images of sex, power, prestige, or sheer fun. They know that people tend to like sex, power, prestige, and sheer fun, and hope that some of this liking will “rub off” on their product. Advertisers thus try to shape your thoughts and feelings; they want you to think more positive thoughts about Coke than Pepsi (or iPhones than Samsung Galaxys, etc.).

In a word, ads are designed to change your attitudes. An attitude is a combined thought and feeling that is directed toward some person, object, or idea. “I don’t like opera,” “I’m against the death penalty,” and “I think all the Kardashians are terrific” are examples of attitudes.

Different types of factors can cause attitude change. Let’s look at three: (1) persuasive messages and their influence on thinking processes; (2) cognitive dissonance that occurs when people act in a manner inconsistent with their attitudes, and (3) mere exposure, that is, attitude change that occurs merely as a result of repeatedly being exposed to an object.

PERSUASIVE MESSAGES AND ATTITUDE CHANGE. Suppose a political ad tells you that a smiling, well-

Systematic information processing is careful, detailed, step-

by- step thinking. If you scrutinize arguments (“Does this candidate really have ‘the best experience’?”) and carefully consider alternatives (“Sure, he’s experienced at government, but maybe he doesn’t know anything else”), you are thinking systematically. Heuristic information processing is thinking that employs mental shortcuts or simple rules of thumb (also see Chapter 8). For example, if you rely on superficial appearances (“He looks like he knows what he’s doing”), you are thinking heuristically.

How systematically are you thinking when you watch TV?

Any given persuasive message may have different effects, depending on whether people are thinking systematically or heuristically. This is evident from research that experimentally manipulated two factors: (1) argument strength (participants heard arguments that were either strong or weak), and (2) information-

This finding explains why advertisers often do not even bother to present strong, carefully worded arguments in TV commercials. Much of the time, people are so distracted that they wouldn’t pay enough attention for the arguments to make any difference.

Systematic and heuristic information processes are two psychological routes through which persuasive messages can change attitudes. Another way of changing attitudes is cognitive dissonance.

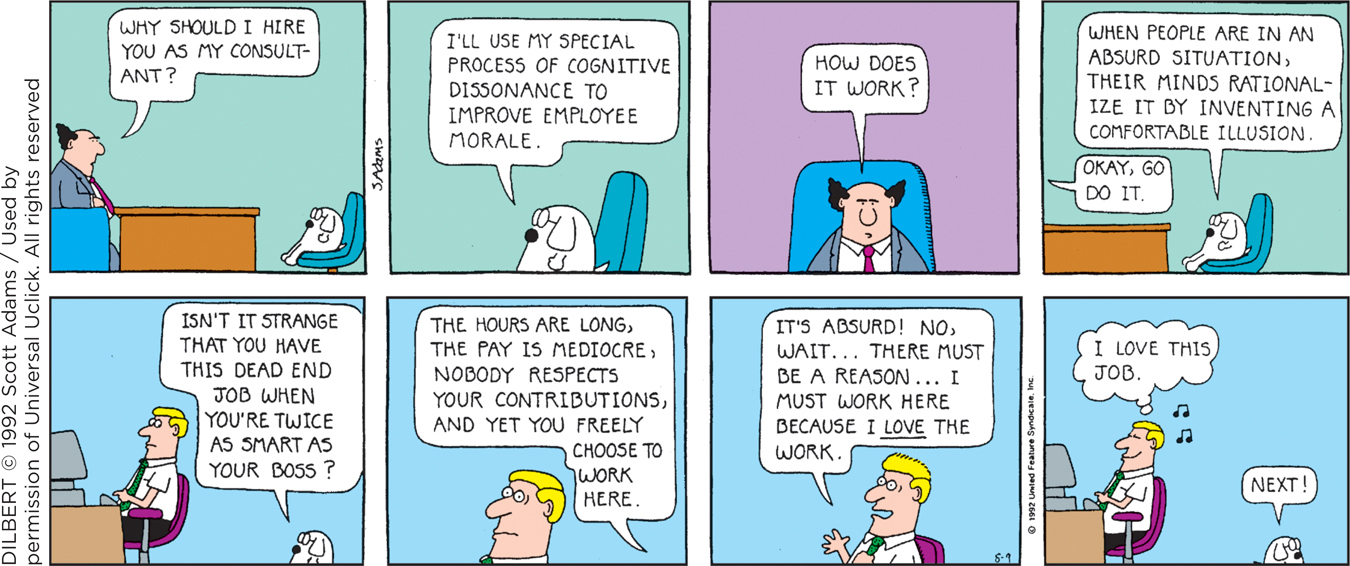

COGNITIVE DISSONANCE AND ATTITUDE CHANGE. Cognitive dissonance is a negative psychological state that occurs when people recognize that two (or more) of their ideas or actions do not fit together sensibly. Here’s an example. Suppose you are an environmentalist, but to make some extra money, you take a part-

529

Cognitive dissonance is psychologically uncomfortable. People thus are motivated to reduce it. One way to reduce dissonance is to change your attitudes. If you convince yourself that “maybe oil drilling in wildlife preserves isn’t all that bad,” your behavior (taking the job) and attitude (“isn’t all that bad”) are not as dissonant anymore. Cognitive dissonance theory predicts that when people engage in behavior that conflicts with their attitudes, the attitudes will change.

Researchers tested this theory by targeting people’s attitudes about a boring task (Festinger & Carlsmith, 1959). In the first step of the experiment, participants spent an hour working on a task that was extraordinarily dull and monotonous (participants turned pegs in a pegboard). Their attitudes toward the task were negative because it was so boring. Afterwards, participants were told that the experiment was over—

Participants were asked to tell the next participant in the study that the experiment was very interesting. This behavior (saying it was interesting) conflicted with participants’ attitudes (that the associated task was boring).

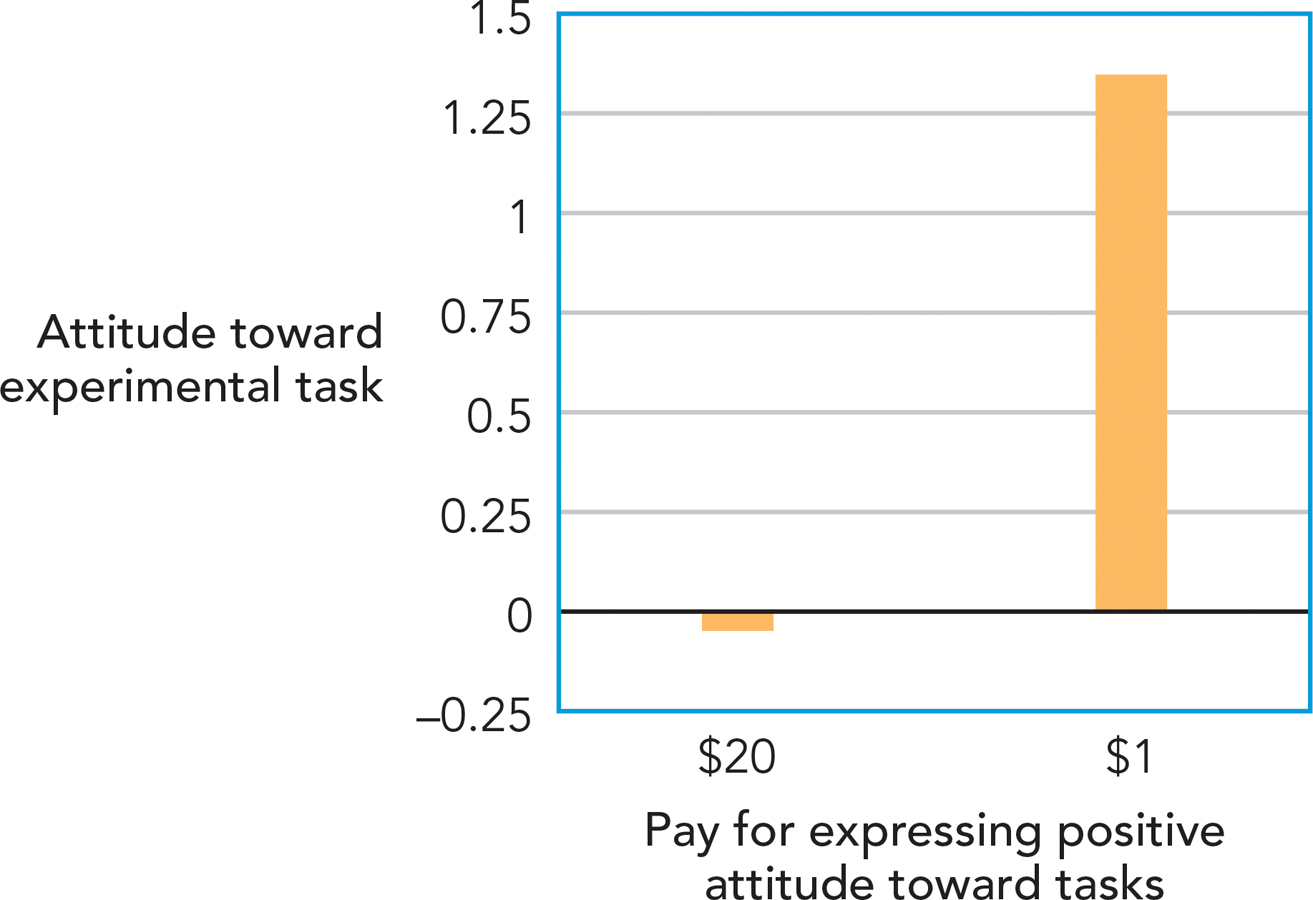

In different experimental conditions, participants were paid either $1 or $20 for telling the next participant that the boring study was interesting.

Later, participants were interviewed by someone who appeared to be unconnected with the experiment, who determined participants’ true attitudes about the experiment and its boring task.

CONNECTING TO MEMORY AND THE BRAIN

530

After all this, who do you think would have more positive attitudes about the experiment? You might guess it was the people who were paid $20 rather than $1; people like getting money. But cognitive dissonance theory predicts the opposite result. When paid $20, people experience little cognitive dissonance because they know why they said that the boring task was interesting: to earn a lot of money. But when paid only $1, the low income does not justify the action of lying to a fellow student. In this condition, participants experienced dissonance between two conflicting ideas: (1) “the task was boring” and (2) “I said it was interesting (for a mere $1).” Just as the theory predicted, this cognitive dissonance produced attitude change (Figure 12.6). In the $1, but not the $20, condition, people’s attitudes toward the task changed, becoming positive. People reduced cognitive dissonance by changing their attitudes.

THINK ABOUT IT

According to cognitive dissonance theory, feelings of dissonance were responsible for the attitude change that occurred in the study where people were paid $1 or $20 to say that a boring task was interesting. How do you know that this is true? The researchers did not measure feelings of cognitive dissonance. Maybe some other psychological process was responsible for the results.

MERE EXPOSURE AND ATTITUDE CHANGE. The first two attitude change techniques we have discussed take effort. To change your attitudes with persuasive messages, companies have to create advertisements. To change people’s attitudes through cognitive dissonance, you have to get them to perform behaviors that contradict those attitudes. A third method of attitude change takes no effort at all. In the mere exposure effect, people’s attitudes toward an object become more positive simply as a result of being exposed to the object repeatedly (Zajonc, 2001).

The mere exposure effect is surprising. You might expect people to be bored by things they see repeatedly, and to like them less. Yet mere exposure reliably makes attitudes more positive (Zajonc, 1980, 2001). In research demonstrating this, participants see pictures of objects. Some are displayed only once or twice, whereas others are shown repeatedly (e.g., 25 times). Participants then indicate how much they like each object. Inevitably, objects seen repeatedly are liked more.

531

TRY THIS!

Mere exposure should seem familiar to you from this chapter’s Try This! activity. There you saw exactly the sort of research procedures that provide scientific evidence of the influence of mere exposure on attitudes.

Three aspects of the mere exposure effect are particularly remarkable:

It works for an extremely wide range of objects. Mere exposure increases the liking of even meaningless objects, such as geometric shapes or words from a foreign language people do not know (Zajonc, 1980).

It works for both people and animals. Researchers played different sounds to baby chicks before they were hatched and then, after the chicks were born, determined which of the various sounds they preferred. The chicks liked the sounds they heard most often before they had hatched (reviewed in Zajonc, 2001).

It works even when objects are shown so briefly that people can’t recognize them. When researchers display pictures of objects for just a few thousandths of a second, the displays are so brief that, later on, people do not remember seeing the objects. Yet they like the ones that are shown more frequently (Bornstein & D’Agostino, 1992).

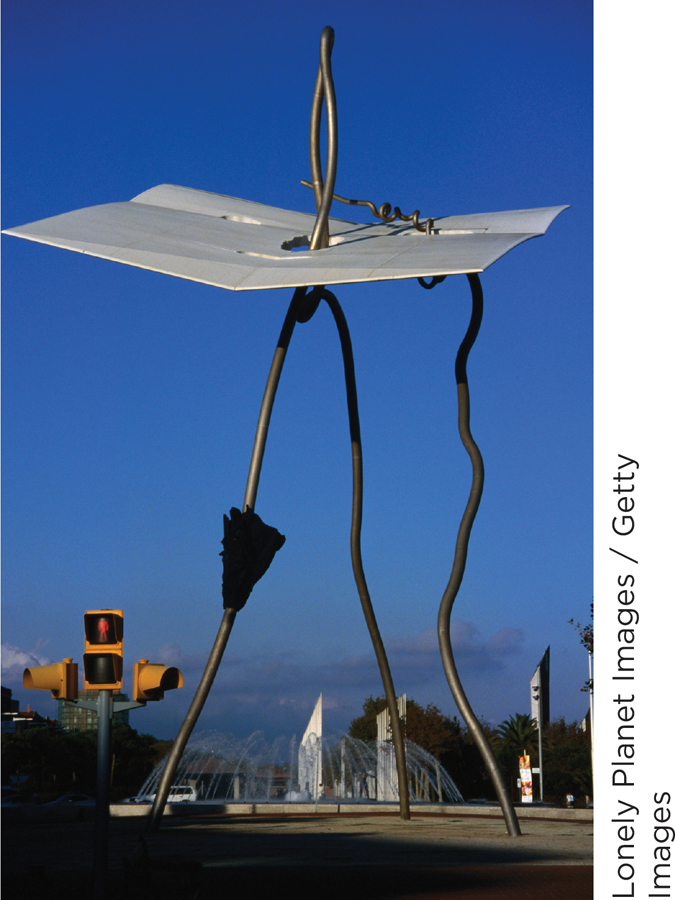

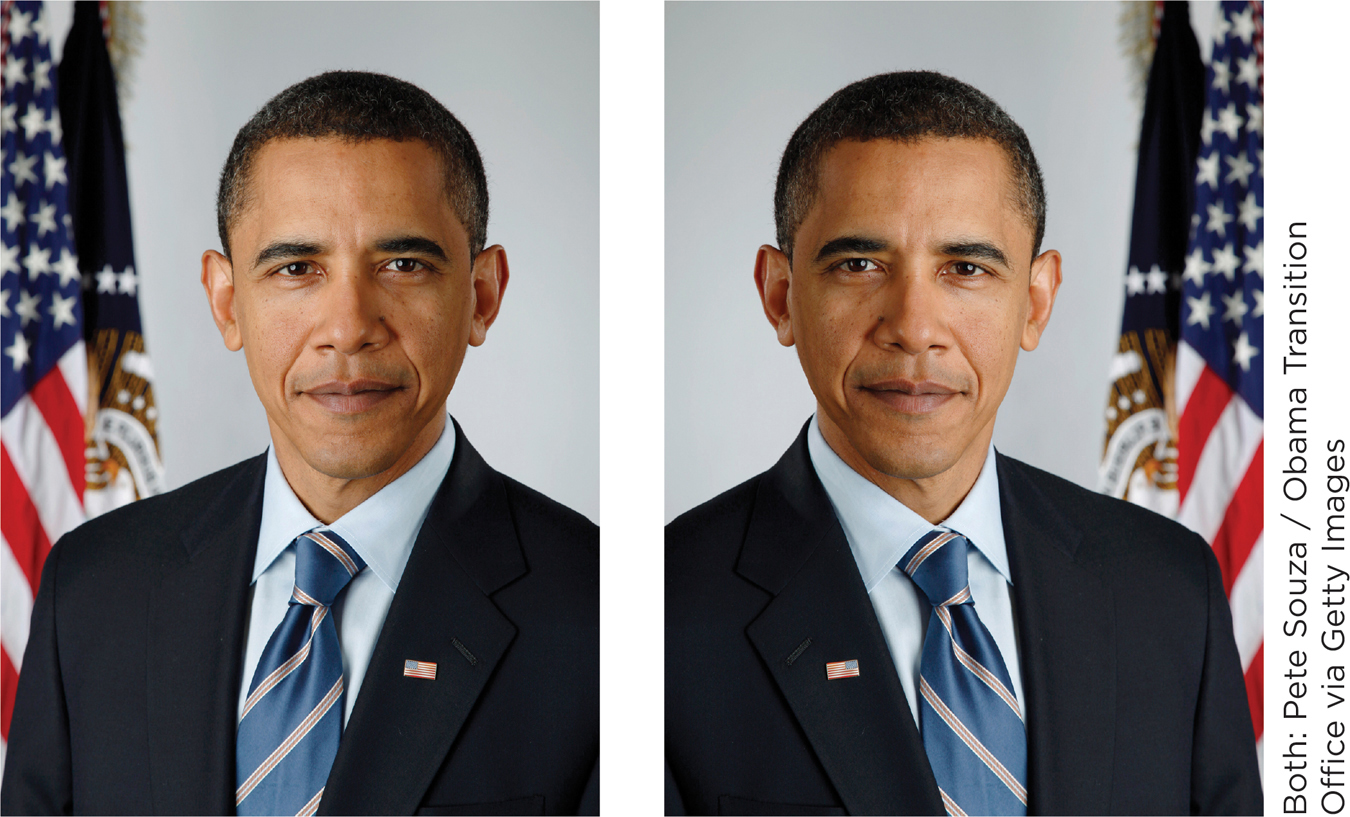

Mere exposure helps to explain phenomena that otherwise would be puzzling. Consider what happens when people are asked which of two photos they like more: a normal picture of themselves or a left–

CONNECTING TO EMOTION AND THE BRAIN

FROM ATTITUDES TO BEHAVIOR. You’ve seen how attitudes can change. A second question is whether attitudes predict behavior.

How could people’s attitudes not predict their behavior? If you have more positive attitudes toward Pepsi than Coke, you buy Pepsi. If you like candidate Williams more than Washington, you vote for Williams. But, reflecting on what you’ve learned in this chapter, you will realize that people’s attitudes often do not predict their behavior. “Teachers” in the Milgram study did not express negative attitudes toward “learners,” yet they administered seemingly lethal shocks to them. It is unlikely that bystanders in the Darley and Latané study had negative attitudes about the person having a seizure, yet many failed to help.

So when do attitudes predict behavior? Under three circumstances (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977):

When situational influences are weak. Powerful situational forces—

the orders in the Milgram study, for example— overwhelm personal attitudes. But when situational influences are weak, attitudes predict behavior. Consider a voting booth. No one can see who you are voting for; situational factors are essentially eliminated. Your voting behavior, then, directly expresses your political attitudes. 532

When people pause to think about their attitudes and themselves. You often go about daily activities without stopping to think, “What is my attitude about this activity?” You might, for instance, have positive attitudes about dental hygiene, but if you have a big exam tomorrow, you might not have time to think about dental hygiene and forget to brush your teeth. Attitudes predict behavior more strongly when people do stop to think about themselves and their attitudes. Social psychologists have demonstrated this through a simple experimental manipulation: the presence of a mirror. Mirrors draw people’s attention to themselves, making it more likely that they will think about their personal attitudes. People’s attitudes predict their behavior more strongly when they are in the presence of a mirror than not (Froming, Walker, & Lopyan, 1982; see Carver & Scheier, 1998).

In what situations do you feel self-

conscious? Do these situations make you more aware of your attitudes? When attitudes and behaviors are equally specific. Consider the following two questions about your attitudes:

How much do you like popular music in general?

How much do you like the band that performed the song you most recently downloaded?

These questions differ in how specific they are. The first question asks about popular music in general, whereas the second asks about one specific band.

Now consider two questions about your behavior:

How much money are you likely to spend on music (downloads and concert tickets) this year?

How likely are you to buy downloads or concert tickets by the band who performed the last song that you downloaded?

Again, the first question is general, and the second one is specific.

Attitudes most strongly predict behavior when the attitude and the behavior being measured are equally specific (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977). In our example, people’s attitudes about music in general might predict their overall music purchasing, and their attitudes about a particular band might predict their purchasing behavior toward that band. But when attitudes and behavior are at different levels—

533

In summary, attitudes do predict behavior, but not always. They predict best when situational factors are weak, people think about their attitudes, and measures of attitudes and behavior are equally specific.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 10

True or False?

- KMJrp2oR+lHQqGyV/E60GJwmOVTaie+2jnl4OStQJt7Q/JB4qpB/+OI9azSalQB8oDbC69OEpuAIiOyiW2VuXU2ZEemvyHALtgriAhVDS7Qrai8C12aHQlBWnH7PULTL7oXTucQGYvi+B0D2iNtDIPTfA6U+CeSgUw4kgXxA1S6/Byz2ZgAvmFph49RGeZ/JjUmOuffCsIsUTXOTzvlmfbvx57IFUr1S3hSvMVQ3c0QoUtLKi0u2pLXwkVNk2dbtRcWkk6+8D4b4DtsUkTcDUZD7lmb1p24coRuLNS/30DvLfaq5yyJj6K3KJXtsHbyBhoP/HILHnpx2zh+7PSb0ZIzeFIYeL8chTHANUg==

- xpHxfoNMdfpbON3/UAbXP0FoZjssG1jxQozdWhfESy/gBZ50jFdLes9w1jWpRZ2B0touUmT+wCf1CJ55bgVrLqO1Im6ajmSy8/nY1Ql9g2zb9hc8+8mYAry+7inl79U0hWphw+JNtbzPulSXIb5cqnwrOs5mytyBZO2EocIsHrdZecCfpfcRlPXPB2FKGsVno2kPzHNpBMVmfTwp0CBRhIPnShSnQ1Zo6IZm/f/BkT2LiYgmUjgMWAaAKHIPMSNIKdlBmDD+nMWvJo++i1d7K4FjQfO9IdA004J/GXfyMFvqIFkkI5SsLrfcc6eTv9LoLbuvx7kCdJc=

- 3gSY5TJVgfYTActKU35Ytj+x/LoYgsaAzyexjbr3yj37Pocbw0QLp+GatiX3p1VSVCStPnqupilEaKQFEhn0jJGGfG5hPzt/4zWSkeGBI3Rb98vrKted1EvTIY0+JQSTjoG1GFj2pOvVgdqUxh5I0GILMpsMxZMWRQPf2RG2X8lJwWuE6ULN6/Scl0bjDu8O706o1Oo9kc/xt3IFyDUO7B/TvrSBCnehjo+H46D9odJDarq2CCL//LmmfppxkTZS5Ru04Q==

Question 11

For each of the scenarios described below, specify whether the attitude is likely to predict the behavior.

- fHt5mhgOiOnZMY92ooFtulxSQzUAIvLBm5qbChJ34HSZmjex7M0t+3sEG17kPdLlW7gwI1UDnr5DiDQwcOHJ8VxpZo+Y2tXt+Yfl5zq+pfd07GEhXp26JcXyoMYLgs9T9fK4tSNN006EQFe+IpnRgSizSrhkeTtfM7XUX2kiGIBqLv1+fOuXKVQPN96etpGBJ9wyqIRKRONCAPNhNaT9eIck5CDRkAqNPxV7fQ==

- dw9e0ELTYPki2YQnw7KWw1lkKu/LwDRNtxIuWBT0YBJqSL4pG0oETc1r+ZGSq+8FxhNq36tNZEBSz9JiMrybMNqGvaHs2Jw8Hmy317rlt7qMED2IbF6efJFipDXzSGaIWTvcjJEEw7QEPVKoiXrb6/eXiVzVPZzx4dnr/X30Cha+B6U9RqAe+fNQaHMsZ33IoSERMZ5otpYi0CpnsrsjDs7tu+7OQX29nd21I/0A2kgXgWHwmy30chjHfXSJR/eOI880LSzX3boeQdpi0ms9w5HvW+SezDgTp9hTM+MA2OGU38Gmps4aP8SGQlh4ebrYasHZ6w==

- /HXsrtM47iKxxUVERgrS5hiy4amLeSy0oFLcqo1Z6dR3Mj5jNf44SqZhyHoP2VhY5yF7RneZJ11j9aCNja7hIwR473AT5WrOwTGlKNt/0FCOmL9Q2ho7r9xDmuZCzRGj2lSBveo913BcbI9PA0CYhNKBs0nUB6biyGpRHMMrxYEOmZ6/AMcCmyqIdUZWMp2cdcPd0l6/CUYwePXV0I5uw1WU2QxQBDZrme5HAqboc1yfe4czORV6Wvug0nr3oh25OINAUoaJAzzQbeLx

a. No; the attitude and behavior are not equally specific. b. Yes; attention is drawn to the self and to one’s attitudes. c. No; situational influences are not weak.

Stereotyping and Prejudice

Preview Questions

Question

Is it even possible to avoid stereotyping?

Is it even possible to avoid stereotyping?

How can being reminded of your own group’s stereotype interfere with intellectual performance?

How can being reminded of your own group’s stereotype interfere with intellectual performance?

How do psychologists measure attitudes that no one wants to admit having?

How do psychologists measure attitudes that no one wants to admit having?

What cognitive, emotional, motivational, and social factors cause prejudice?

What cognitive, emotional, motivational, and social factors cause prejudice?

How can prejudice be reduced?

How can prejudice be reduced?

Not all beliefs are equally important to the life of society. Some, such as our views of sports teams, soft drinks, or celebrities, play only a minor role. Others affect the fabric of social life. One of these is stereotypic beliefs.

A stereotype is a simplified set of beliefs about the characteristics of members of a group. For instance, a person who believes that everyone of British ancestry is intelligent but aloof, or that all people of Italian ancestry are friendly and emotional, would be said to hold stereotypes about those groups.

Stereotyping has been a part of human life throughout history. One after another, different groups have been the target of negative stereotypes, with members of other groups seeing them as, say, cheap, lazy, aggressive, unintelligent, or unscrupulous. Sometimes stereotypes contain positive content, too; for example, in U.S. society there is a stereotype that Asian Americans are particularly skilled at mathematics (Cheryan & Bodenhausen, 2000). (Though it contains positive content, this stereotype can have social costs for Asian Americans; Wong & Halgin, 2006.)

534

The presence of stereotypic beliefs in a society fosters prejudice, which is a negative attitude toward individuals based on their group membership. Disparaging thoughts and feelings about individuals in a group are the hallmark of prejudice.

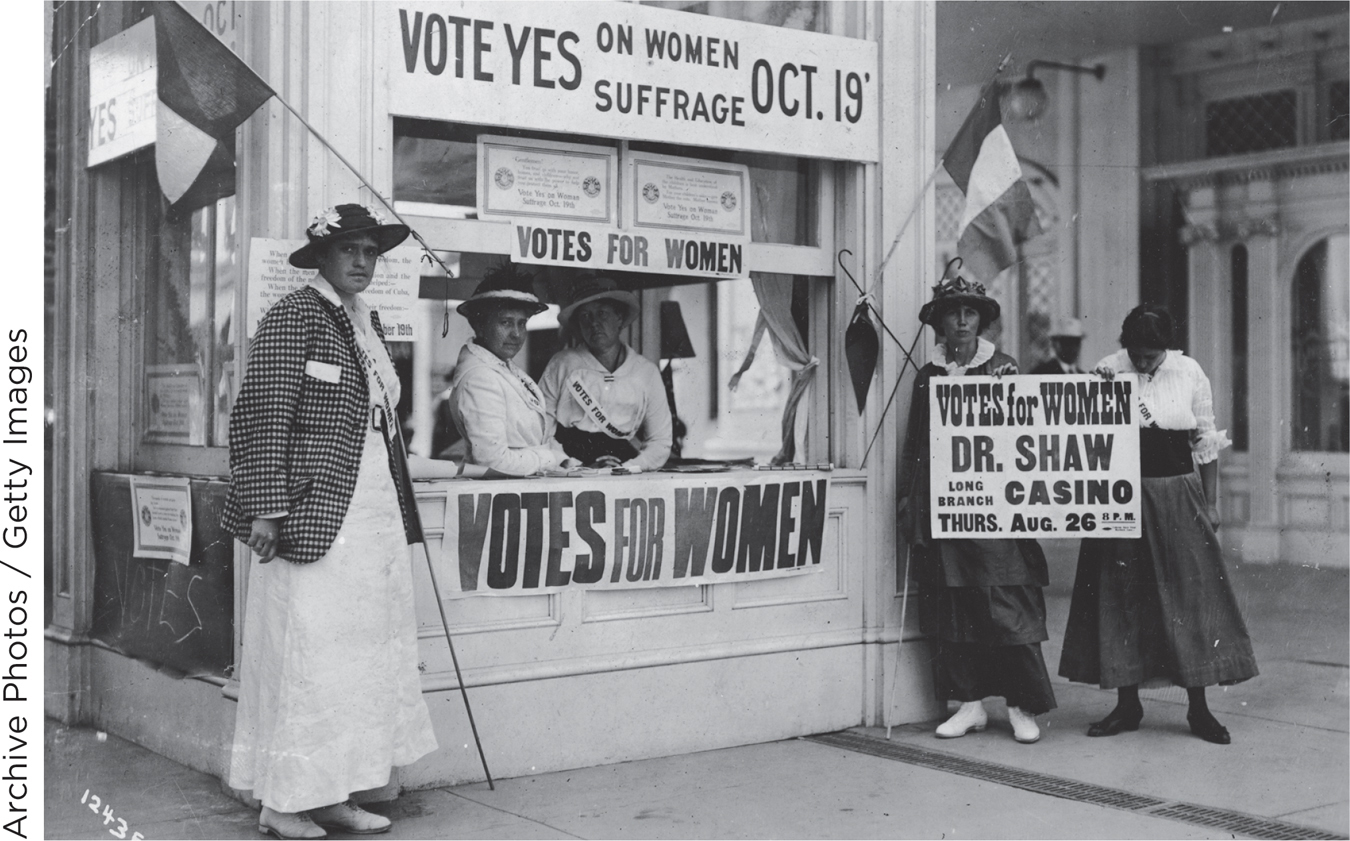

Stereotyping and prejudice, in turn, contribute to discrimination, or the unjust treatment of people based on their membership in a particular group. The history of the United States, a nation founded on the notion that all people are created equal, is laced with examples of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. For example, members of the group “women” could not vote until the year 1920. Members of the group “Black” could not be sure of exercising this basic right until the passage of the national Voting Rights Act in 1965.

SOCIAL-

In a study of automatic and controlled thinking (Devine, 1989), a researcher first identified two groups of participants: people (1) high and (2) low in racial prejudice toward African Americans. She then gave both groups two tasks:

Automatic thinking: The task measured the degree to which words stereotypically associated with African Americans automatically influence people’s thoughts.

Controlled thinking: People wrote down thoughts that came to mind for them when they thought of African Americans; the task measures controlled thinking because people can control what they write, excluding certain thoughts that come to mind.

When have you had to remind yourself to rethink a stereotype?

On the first task, the groups did not differ. The automatic thinking measure revealed that stereotypic thoughts can pop into anyone’s mind. But on the second task, they did differ; low-

The lesson is that, if you live in a society with stereotypes, it is almost impossible not to learn them. However, you can counteract prejudice by reminding yourself, through controlled thinking processes, that stereotypes are simplistic, inaccurate portrayals of your fellow citizens.

STEREOTYPE THREAT. The research on stereotyping we just discussed focuses on people who hold stereotypes. But what about those who are the targets of stereotypes?

Research pioneered by Claude Steele (whom you met in the opening pages of this book) shows that stereotypes can harm people’s intellectual performance. This occurs through stereotype threat, which is a negative emotional reaction people have when they realize that they might confirm a negative stereotype about their group (Steele, 1997). When threatened by a stereotype, people perform less well on tests of intellectual ability.

535

Stereotype threat occurs when three factors coincide:

An individual is trying to perform well on a task.

The individual belongs to a group that, according to a social stereotype, is expected to perform poorly on this task.

The individual is reminded of the stereotype.

When these occur together, people face a psychological threat: They might confirm the negative stereotype. Even if they know the stereotype to be false, they still may worry about performing in a way that confirms it. These worries can interfere with people’s performance, causing them to achieve at levels below their true ability.

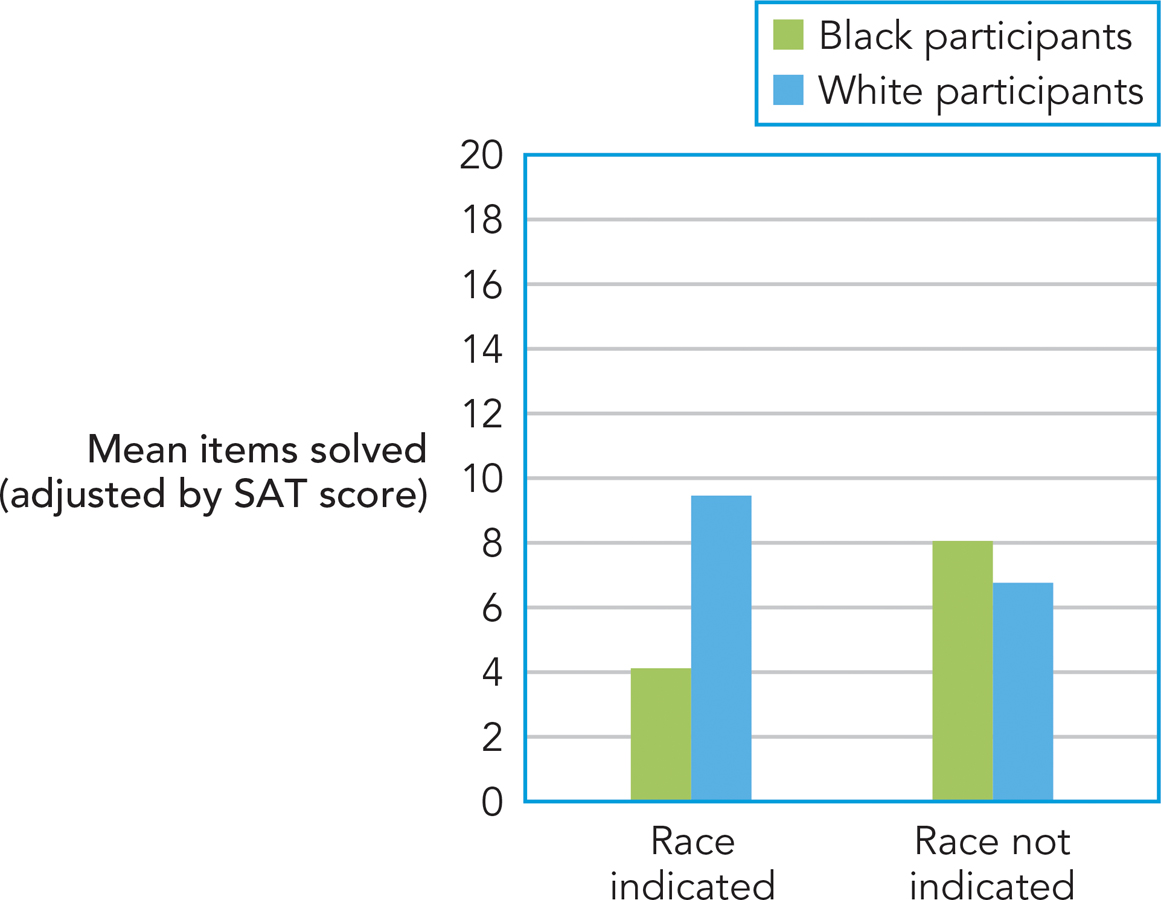

Steele tested this idea in a study of stereotype threat among Black college students taking an intellectually challenging test. White and Black students completed the test in two different experimental conditions. In one, they simply took the test. In the other, they first completed a demographic questionnaire asking them to indicate their racial background. This simple manipulation affected test scores. When participants indicated their race—

Racial and ethnic stereotypes are not the only ones that can create stereotype threat. Another is gender stereotypes. Women are subjected to a stereotype portraying them as inferior to men in math. Research shows how this stereotype can affect performance. In one experimental condition, male and female participants were told that, on a set of math problems they were to attempt, men’s and women’s test scores usually differed (information consistent with the stereotype). In this condition, men outperformed women. However, in another experimental condition, participants were told that men’s and women’s scores usually did not differ on the math problems they would be given—

A meta-

IMPLICIT MEASURES OF STEREOTYPES AND PREJUDICE. In the study of stereotypes and prejudice, a big scientific challenge involves measurement. Suppose one tried to measure racial stereotypes by asking people, “Do you think that [people of a given ethnic group] are inferior to your group?” You can see the problem: Even people who believe their group is superior may not want to admit that they think this. People might not answer honestly. What you need is some strategy to measure stereotypic beliefs that does not rely on explicit self-

An implicit measure is one in which participants cannot tell what a psychologist is measuring. The test does not contain explicit statements that would give participants clues about its purpose, and when taking the test, participants do not directly report on their personal qualities. Nonetheless, the test measures people’s beliefs. To see how implicit tests work, let’s look in detail at one: the implicit association test, or IAT (Greenwald, McGhee, & Schwarz, 1998).

536

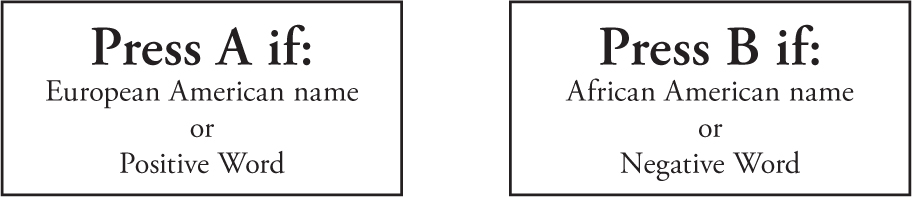

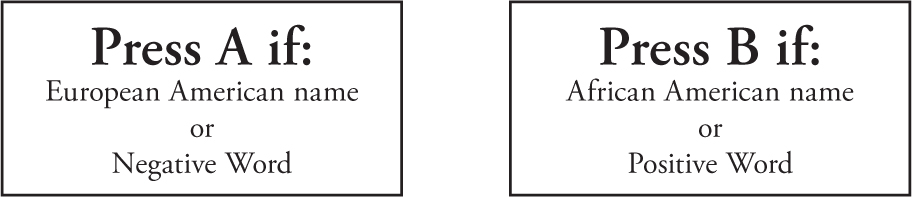

In an IAT that measures racial stereotypes, participants are shown two types of stimuli: (1) names that are typically European American (Heather) or African American (Ebony), and (2) words that are either emotionally positive (“happy”) or negative (“evil”). When a name or word appears, participants must press, as quickly as possible, one of two keys on a computer keyboard. On some experimental trials, participants are asked to press the keys according to the following rule:

On other trials, they press the keys according to another rule:

When people’s personal thoughts match the rules of the task, they perform the task more quickly. If, for example, people have mostly positive thoughts about European Americans and negative thoughts about African Americans, they would perform the task more quickly when a negative word is paired with an African American name than when a negative word is paired with a European American name. The measure of stereotyping compares the speed with which people perform the task under the two conditions.

What implicit beliefs would you be surprised to learn you held?

Research shows that European Americans perform the task more quickly under the first condition than the second. Even among European Americans who disavow racial stereotypes when asked explicitly about race, the IAT reveals an implicit preference for European American names (Greenwald et al., 1998). In the years since the IAT’s development, many studies have found that implicit measures reveal stereotypic beliefs and attitudes that are not identified by traditional questionnaires (Petty, Fazio, & Briñol, 2009). Implicit measures of attitudes open a window into the mind, revealing mental content that previously was hidden.

PREJUDICE: ORIGINS AND REDUCTION. How did prejudice originate? And, whatever its origins, how can it be reduced? Let’s conclude our coverage of stereotyping and prejudice by addressing these questions.

When searching for origins of prejudice, there are two factors to consider: (1) psychological processes and (2) historical factors, specifically, the history of the people toward whom prejudice is directed.

Gordon Allport (1954) discussed three psychological processes that contribute to prejudice: generalization, hostility, and scapegoating:

Generalization occurs when people regard different things as essentially the same. When people think that all individuals in a group are basically the same—

that is, when they generalize about a group— they are more likely to become prejudiced toward it. Hostility is a negative emotion that people direct toward others who are seen as rivals or enemies. When people see themselves as competing with another group, they are prone to express hostility verbally, for example, by using ethnic or racial slurs.

537

Scapegoating occurs when people who are frustrated with their own circumstances blame members of another group for their plight (Glick, 2005). This blame may reflect people’s motivation to maintain a positive view of themselves, which they can do by avoiding thoughts about their own faults and shifting blame onto others (Newman & Caldwell, 2005). Allport illustrated this with the example of a worker who “was unhappy in his job … had failed to become an engineer as he had once hoped … [and] railed against ‘the Jews who run this place’” even though, in reality, “not a single Jew was connected with either the ownership or the management” (Allport, 1954, p. 349).

An analysis of general psychological processes, such as Allport’s, is valuable yet limited. It implies that individual cases of prejudice can be understood as examples of the three psychological processes (hostility, generalization, and scapegoating). Yet some cases of prejudice may require not only a psychological analysis, but also a historical one. Consider the case of African Americans.

The psychologists Stanley Gaines and Edward Reed (1995) have argued that a full understanding of prejudice and the African American experience requires that one confront the unique history of this group. The African American experience involves not only generalization, hostility, and scapegoating, but also “the exploitation of a people [who were] stripped forcibly of home, property, and, to some extent, culture and family” (p. 99) in the slave trade.

Gaines and Reed draw on the insights of the great African American scholar W. B. Du Bois, who identified a unique aspect of African American psychological experience. Du Bois explained that African Americans experience a “divided social world” (Gaines & Reed, 1995, p. 99). On the one hand, they are Americans—

Whatever its roots, can prejudice be reduced? A large body of research (Paluck & Green, 2009) suggests that it can—

The cases of stereotyping and prejudice we have reviewed occurred in one region of the world, the United States. Let’s now widen our world view by considering questions of culture.

538

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 12

Thanks to KIRHMLAUgWIHggQsFPWgkg== thinking processes, people are able to counteract prejudice. Reminding people that they belong to a group for which there is a stereotype may cause them to worry that they will wyzU/lHXJWm27V8R that stereotype. When doing the IAT, people who associate men with science and women with humanities would perform the task more quickly when a science word is paired with a UxjGNm5HTY69onVGFK9iwTmY4DmaHQMcBA4xxg== name than when a science word is paired with a ioSZ7ORt3/oCMIinqkL2GcpX9mcUs/u0UnsSIA== name. Allport identified three processes inherent in prejudice: generalization, hostility, and zX+mVJllZTLDB4Q7cfbAgwfwIKI=, but ignored prejudice that was rooted in the exploitation of African Americans in the O9YrN1cy0HZtQGIE trade.