12.3 Culture

In your daily life, you take a lot of things for granted; certain behaviors are so common that you give them little thought. Consider these:

When you meet somebody, she tells you her name and asks yours.

If a child is given a toy, he sees it as his personal property and puts it in his toy chest.

If you talk to a physician about a seriously ill relative, she may provide a medical prognosis, including an estimate of how much time the relative has left to live.

There’s nothing surprising about these examples. It’s normal to learn a person’s name, to treat a gift as personal property, and to get a medical prognosis from a doctor. Pretty much everyone you know does these things and believes them to be appropriate.

In any large group of people, there inevitably are beliefs about people, social settings, and the world at large that all essentially share. People’s shared beliefs, and the social practices that reflect those beliefs, constitute a group’s culture.

What cultural practices do you take for granted, if any?

Knowing the cultural beliefs and practices of your group is essential for navigating everyday life. Cultural knowledge enables you to figure out what things mean (Geertz, 1973). Without this knowledge, everyday circumstances can be baffling. Tourists, for example, often lack this knowledge and experience culture confusion (Hottola, 2004). When traveling in a new part of the world, they notice that their native cultural knowledge does not fully apply to their current circumstances. Everyday encounters—

Travel Etiquette Recommendations

In Asia, never touch any part of someone else’s body with your foot.

In Fiji, an affectionate handshake can be very long, and may even last throughout an entire conversation.

In Nepal, it is considered bad manners to step over someone’s outstretched legs, so avoid doing that.

In Italy, pushing and shoving in busy places is not considered rude, so don’t be offended by it.

— Robert Reid (2011)

Cultural Variability in Beliefs and Social Practices

Preview Question

Question

What are some examples of how culture shapes what we think and do?

What are some examples of how culture shapes what we think and do?

Cultures vary; what is commonplace in one may be taboo in another. For example, you might think people always say their name and ask for yours when introduced. But they don’t. On the Indonesian island of Bali, names traditionally have been “treated as though they are military secrets” (Geertz, 1973, p. 375). Balinese introduce themselves instead by referring to their place in their community (e.g., “I am the village chief”) or family (“I am the mother of the village chief”). This social practice reflects the culture’s great valuing of community and family ties (Geertz, 1973).

The other behaviors listed at the beginning of this section also vary culturally. In some cultures outside the United States, people view property as shared rather than personally owned. A child might see a toy, or an article of clothing, as family property rather than personal property (Trumbull, Rothstein-

539

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 13

If you were to meet someone in Bali, you would be wise to keep your name secret and instead introduce yourself according to your place in the TpWUCuB4HR3AuJrKBLl6Rw==.

Cultural Variability in Social Psychological Processes

Preview Question

Question

What assumption can social psychologists be faulted for making?

What assumption can social psychologists be faulted for making?

Now that you’ve read about cultural variability, think back for a moment to the material earlier in this chapter. The social psychology experiments discussed had something in common. Did you notice it? Almost all of them were carried out in the same culture, namely, that of the United States or Western Europe, or what is generally called “Western” culture. Would the research have yielded the same results in different cultures?

For many years, social psychologists rarely asked this question. They assumed that their research results would be the same anywhere in the world. More recently, however, the field of cultural psychology (Kitayama & Cohen, 2007; Shweder & Sullivan, 1993) has emerged, grown rapidly, and questioned this assumption. (The growth is evident in the Cultural Opportunities features that appear throughout this book.) Cultural psychology is a branch of psychology that studies how the social practices of cultures and the psychological qualities of individuals mutually influence one another. Let’s revisit one of the topics explored earlier, attribution, and view it through the lens of cultural psychology.

CULTURAL OPPORTUNITIES

Social Psychology

As you have seen, each chapter of Psychology: The Science of Person, Mind, and Brain explores the role of cultural factors in psychological experience. The study of culture is particularly prominent in social psychology. Today’s social psychologists recognize that people’s beliefs about social situations—

The theory and research described throughout this section on culture show how social psychology has advanced by seizing upon the opportunity to study behavior and cognition in cultural contexts.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question 14

kw8/+LHVvSH3r8uvp1GlDA== psychologists question the assumption made by social psychologists that research results should generalize everywhere in the world.

Culture and Attribution to Personal Versus Situational Causes

Preview Question

Question

Just how fundamental is the fundamental attribution error?

Just how fundamental is the fundamental attribution error?

In 1984 psychologist Joan Miller ran a study that, in some respects, looked like a traditional attribution experiment. She asked participants to explain some everyday actions. Based on fundamental attribution error research, you would expect her participants to overestimate the causal impact of people and underestimate the impact of situations. Miller, however, took an extra research step: conducting the study in both the United States and southern India. Hers was a cross-

540

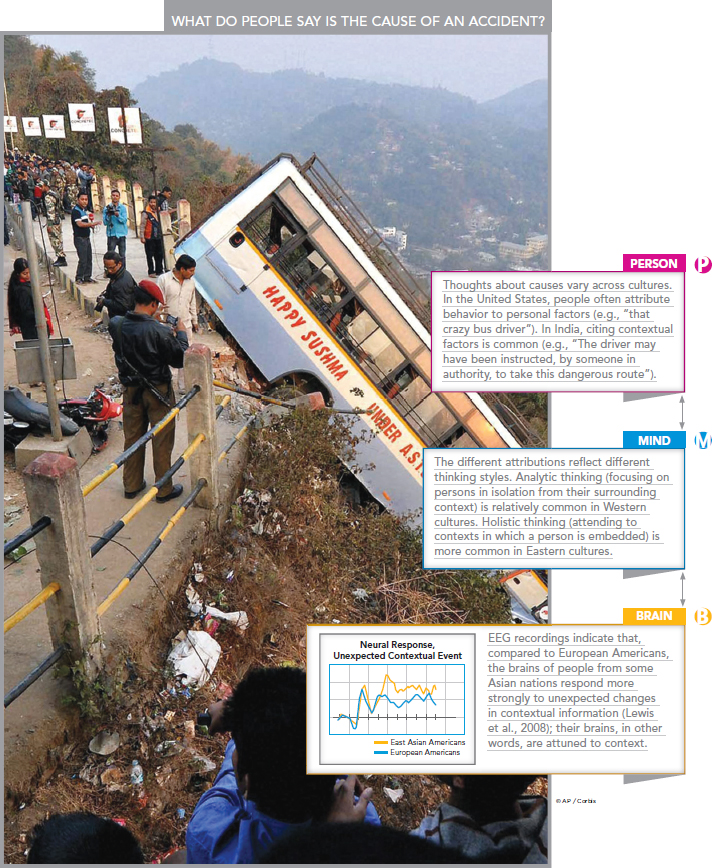

Her work identified cultural differences in attribution. People in the United States primarily explained other people’s behavior in terms of person qualities, for example, “That’s just the type of person she is” (Miller, 1984, p. 967). Citizens of India, though, more frequently made attributions to social context; for example, “The man is unemployed” or “She did not have the [social] power” to act differently (Miller, 1984, p. 968). In India, then, the fundamental attribution error was not nearly as evident as in the United States.

Subsequent research confirmed this finding. When making attributions about the causes of events such as crime or sports performance, people in countries in the Middle East, South Asia, and East Asia are less likely than Americans to attribute behavior to personal dispositions; they more frequently cite situational factors (Oyserman, Coon, & Kemmelmeier, 2002).

Why do the cultures differ? One possibility is differing cultural beliefs and practices (Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, 1995). In the Western nations of North America and Western Europe, the dominant culture is individualistic—one that emphasizes individual rights to pursue happiness, speak freely, and “be yourself.” Many Eastern (e.g., South and East Asian) nations have collectivistic cultures, which emphasize individuals’ ties to larger groups (or “collectives”), such as family, community, and nation. Collectivistic cultural practices highlight the obligations of the individual to his or her society.

Different cultures foster different ways of thinking (Nisbett et al., 2001). People who develop in collectivistic cultures tend to think holistically. In holistic thinking, people pay attention to the overall setting—

The holistic/analytic distinction explains the cultural variation in attribution discovered in the study by Miller. The holistic thinking of Eastern cultures draws people’s attention to situational factors rather than to qualities of the person whose behavior is being explained. As a result, people consider situational factors when explaining behavior, thereby avoiding the fundamental attribution error.

THINK ABOUT IT

What other psychological processes, beyond attributions, might vary across cultures? Might cultures differ in the degree to which they experience cognitive dissonance? Or are influenced by pressures for conformity?

Brain research provides additional evidence that cultures differ in analytic and holistic thinking (Lewis, Goto, & Kong, 2008). The research participants, Americans of either European or East Asian (primarily Chinese) ancestry, were shown a series of stimuli. Some were “target” stimuli on which participants focused most of their attention. Others were contextual stimuli, that is, visual information that was part of a background context. On some trials, the background context changed unexpectedly. EEG recordings measured the degree to which participants’ brains responded to this change. Findings showed that the brains of East Asian Americans changed more; their brains responded more strongly to changes in background context (Figure 12.8). This means that different cultural practices (individualistic and collectivistic) can produce not only different thinking styles (analytic and holistic), but also different types of brain activity in members of the cultures.

Now that we have seen how the study of the brain can deepen one’s understanding of culture and thought, let’s focus our attention on social cognition and the brain.

541

542