13.7 Personality and the Brain

The history of personality psychology (Lombardo & Foschi, 2003) exemplifies the person-first theme of this textbook. Personality psychology began at a person level of analysis; theorists such as Freud, Rogers, and Bandura studied people in therapy and in everyday social contexts. Next, the field moved to a mind level. Researchers explored cognitive and emotional processes that might explain people’s distinctive personality styles (e.g., Cantor & Kihlstrom, 1987; Cervone, 2004; Erdelyi, 1985).

In recent years, researchers have been able to move down a level, to the brain. Let’s see how brain research has deepened psychology’s understanding of two types of personality processes: (1) unconscious processes (as emphasized in psychodynamic theory) and (2) conscious, self-reflective processes (as emphasized in humanistic and social-cognitive theories).

Unconscious Personality Processes and the Brain

Preview Question

Question

Does research on the brain support the idea that thinking can occur unconsciously?

Does research on the brain support the idea that thinking can occur unconsciously?

Freud’s theory of the unconscious mind is psychological, not biological. Freud never identified parts of the brain associated with his psychodynamic structures and processes—but he wanted to. Freud began to formulate a biological theory of mind early in his career (Pribram & Gill, 1976), but abandoned the effort after concluding that scientific knowledge at the time was insufficient to support a biologically grounded theory of unconscious processes.

Times have changed, thanks to advances in biology. Today, psychologists recognize that biological evolution naturally gave rise to a mind that, to a large degree, acts unconsciously (Bargh & Morsella, 2008). During the course of evolution, quick, unconscious processes were often beneficial compared to slow, conscious ones; when chasing prey or avoiding predators, there’s no time to sit around consciously deliberating on the best course of action. Organisms benefit from an unconscious mind that triggers actions rapidly.

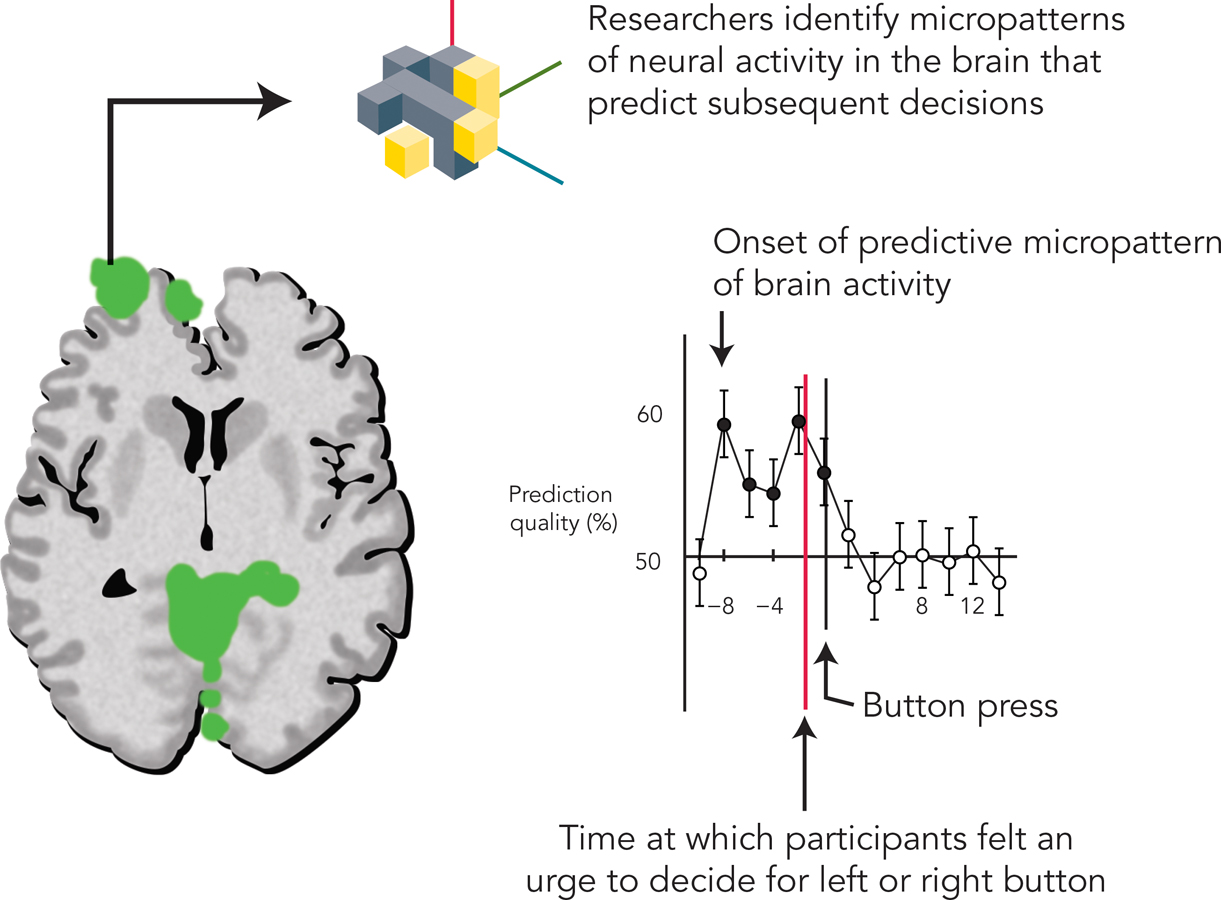

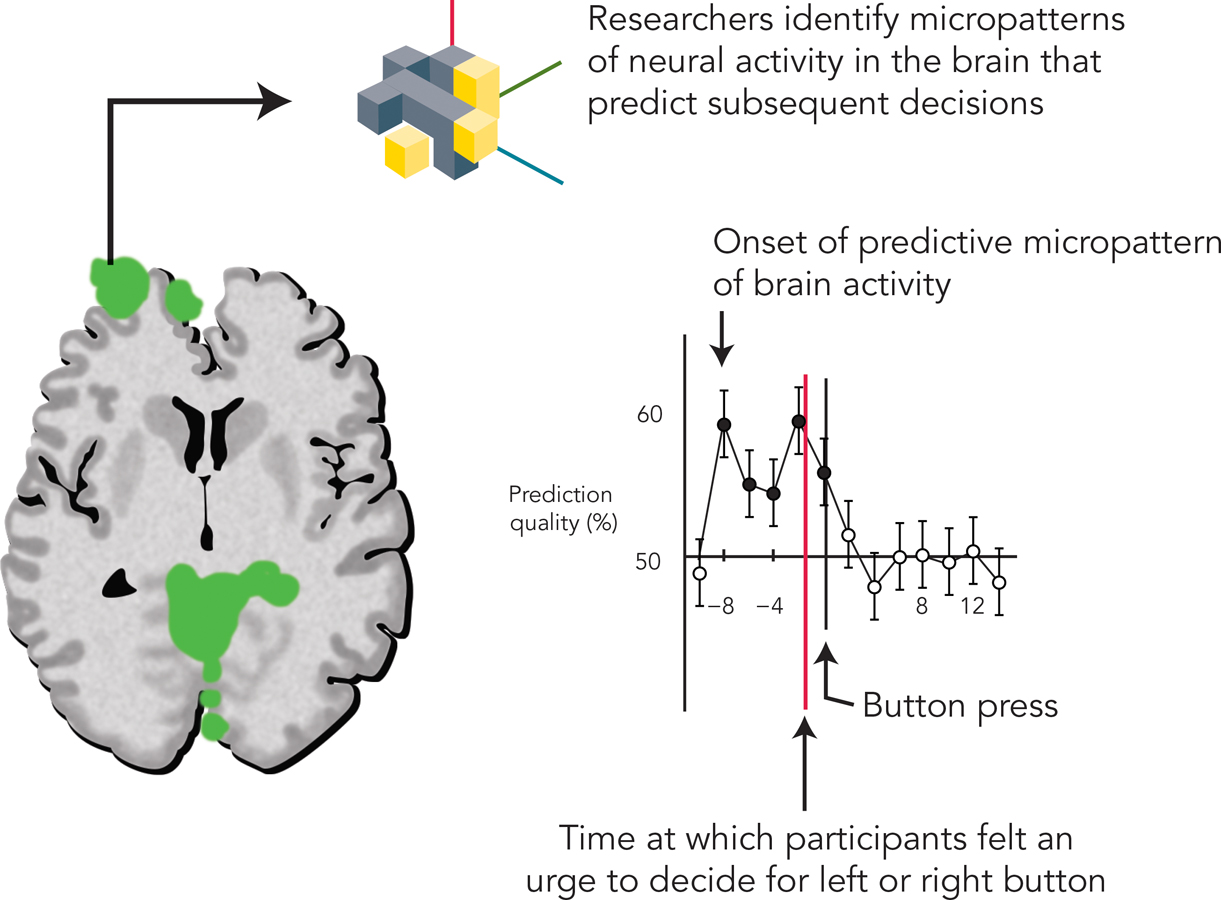

This evolutionary reasoning suggests that brain researchers should be able to identify regions of the brain that trigger people’s decisions even before they are consciously aware that they have decided. In one experiment with this goal, researchers studied a simple decision: when to press a button. Participants were asked to press one of two buttons whenever they “felt the urge to do so” (Soon et al., 2008, p. 543). To find out when people had the conscious experience of deciding to press a button, researchers flashed a series of letters on a computer screen and asked participants to remember which letter was on screen when they felt they were making their decision. (The researchers knew exactly when each letter appeared and thus could pinpoint the time at which participants had the conscious experience of making a decision.)

Throughout the task, fMRI was used to record participants’ brain activity. The researchers identified two brain regions that predicted button pressing; in other words, when these regions became active, participants pressed a button soon afterward. Researchers then compared two time points: (1) when the brain regions became active, and (2) when people had the conscious experience of making the decision.

Of critical importance is that the brain activity occurred well before the conscious experience—often 7 to 10 seconds earlier (Figure 13.11). The implications are remarkable: The researchers could determine (from recordings of brain activity) when participants would press a button before the participants themselves knew (from their conscious experience) when they would do so. This and related findings (e.g., Libet et al., 1983) suggest that, outside of conscious awareness, brain systems “make a decision” and subsequently send information about the decision to the conscious part of the mind.

figure 13.11 Decision making and conscious awareness To determine when people had the conscious experience of making a decision, researchers recorded (1) when they were consciously aware of making the decision, and (2) brain activity that might predict decision making. Researchers identified a brain region that became active and predicted decision making 7 to 10 seconds before people were aware that they were making decisions. The results highlight the role of nonconscious processes in decision making.

Another study provides a brain-level analysis of the phenomenon that launched Freud’s psychodynamic theory of personality: the impact of mental content (memories, thoughts) on physical symptoms. Researchers (Voon et al., 2010) studied patients with conversion disorder, in which people experience physical symptoms—for example, odd muscular movements such as tremors and tics—that cannot be explained by any medical condition (also see Chapter 16). Their physical symptoms thus appear to have mental causes. What could connect the mental and the physical? Brain-imaging research indicated strong connections between the motor area (which controls muscular movement) and the amygdala (which is involved in emotional arousal). Just as Freud might have predicted, among people with conversion disorder, when the emotion region of the brain became active, the motor area of the brain became active, too. This emotion–motor connection in the brain was not seen in a second group of people who did not have conversion disorder.

THINK ABOUT IT

How do contemporary research findings on unconscious processes relate to Freud’s theory? Is the unconscious studied in today’s research the unconscious of Freud—one dominated by sexual and aggressive urges and repressed memories?

Connections in the brain thus may explain the connections between mind and body first analyzed by Freud. In patients with conversion disorder, emotional arousal may directly disrupt motor movements.

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question

29

Brain lnxJGKu/HgYPg+4f research indicates that different brain regions become active during conscious and wz8QzcBShAoTruTfgCNO+g== processing. It also indicates that among those with N4/MEd4DBIwKmYlSZa7GVA== disorder, there are strong connections between the emotion region, or the XXrTlZEqkB70qv+z3zFo3w==, and the motor area of the brain, which helps to explain why emotions can disrupt movements.

Conscious Self-Reflection and the Brain

Preview Question

Question

How have researchers studied the brain and people’s ability to think about themselves, or self-reflect?

How have researchers studied the brain and people’s ability to think about themselves, or self-reflect?

As you learned earlier, both humanistic and social-cognitive personality theorists analyzed the self, arguing that people’s reflections upon themselves are a central personality process. They made these arguments on psychological, not biological, grounds. At the time the theories were formulated, researchers had little knowledge of the brain systems involved in self-reflection.

Again, times have changed. In the past decade, researchers have begun to identify the neural systems that enable people to reflect upon, and develop knowledge about, themselves (Lieberman, Jarcho, & Satpute, 2004).

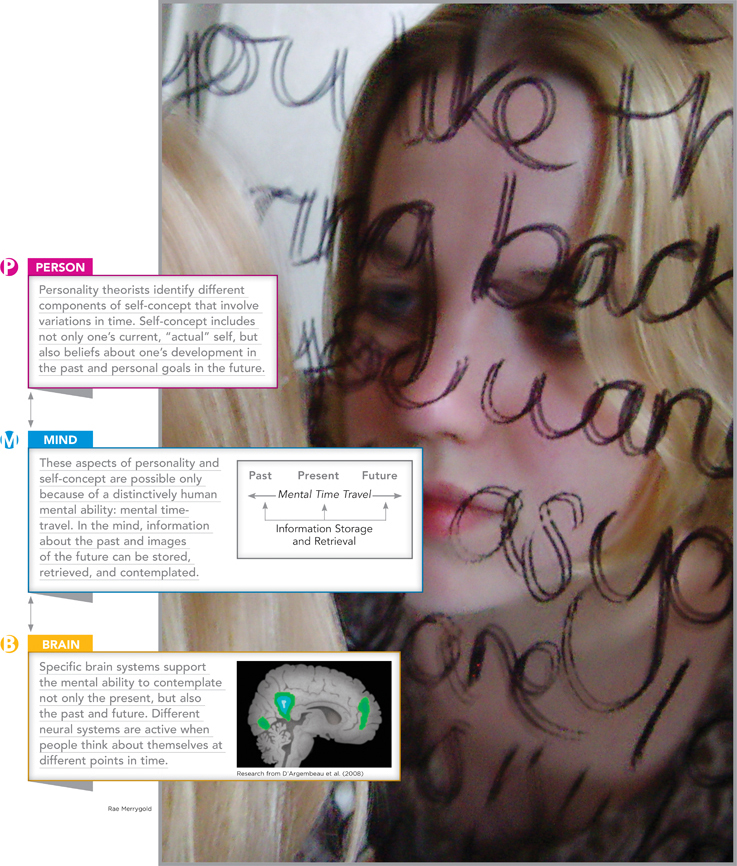

One line of research has explored self-reflection and the brain through a two-step strategy (D’Argembeau et al., 2008). The steps exemplify the mind and brain levels of analysis we have discussed throughout:

Distinguish among mental processes: The first step was to distinguish among different types of mental processes. Here, a key factor to consider is time. Sometimes people store information about, and reflect on, their current self—their present, here-and-now psychological characteristics. Other times people store and reflect on information about their past or future self—psychological characteristics they possessed earlier in life or might possess someday.

Identify neural system in the brain: The second step was to identify brain systems that come into play during these different types of mental processes involving the self. The researchers used brain imaging to accomplish this, in the following research procedure.

Self-reflection, the psychological activity of thinking about one’s own characteristics, has long been the focus of art (as shown here in Picasso’s Girl Before a Mirror). In twentieth-century personality theory, it was the focus of psychology, as personality theorists came to view self-reflection as a central personality process. In the twenty-first century, self-reflection is also targeted by neuroscientists, who search for brain regions that give people the power to reflect upon themselves.

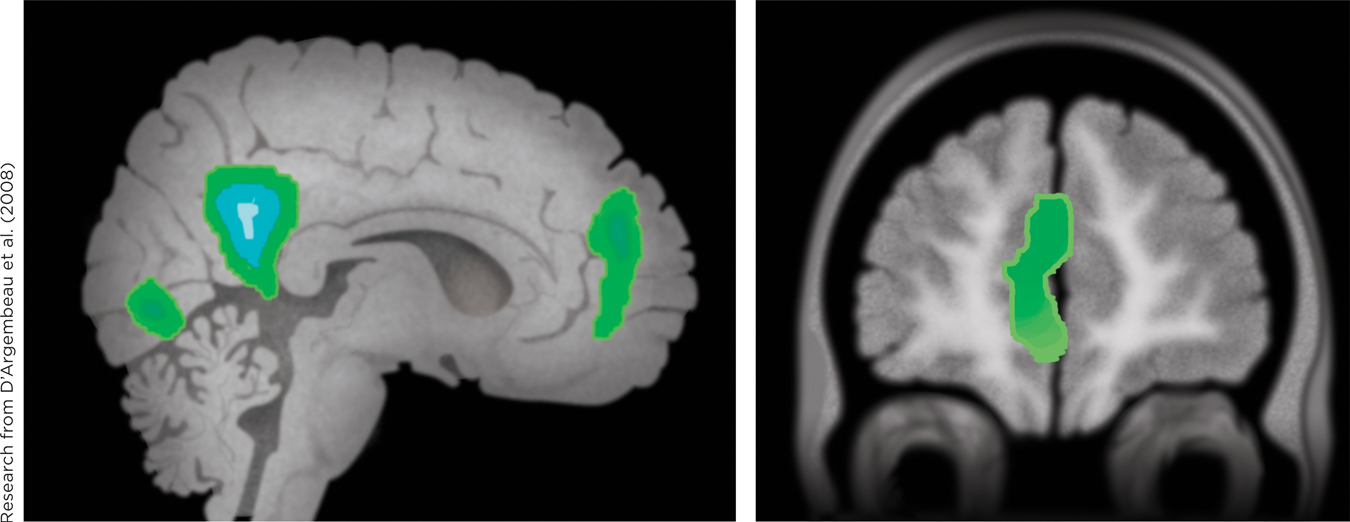

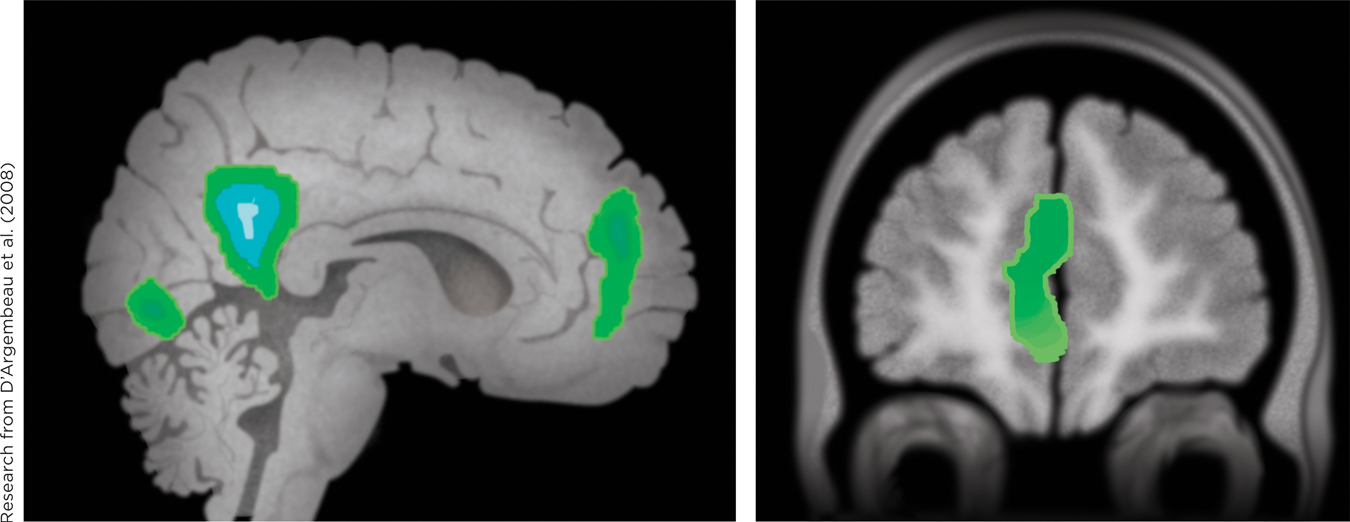

Participants rated a series of adjectives (e.g., “modest,” “shy”), judging, for each one, whether the word described them (D’Argembeau et al., 2008). In different experimental conditions, participants reflected on whether the words (1) described them now (their present self) or (2) described them as they were five years ago (their past self). They also rated whether adjectives described a close friend now and in the past; this combination of conditions enabled the researchers to identify regions of the brain that are most active specifically when people reflect upon themselves. Self-reflection, they found, was associated with cortical midline structures, that is, with activation in the middle of the upper regions of the brain; see Figure 13.12 (the cortex; Chapter 3). Central regions of the frontal cortex and rear, or posterior, cingulate cortex were more active when participants thought about themselves in the present than the past.

figure 13.12 What your brain may have looked like when you did the exercise at the beginning of this chapter. Researchers took brain images while participants engaged in the same sort of task you performed at the start of this chapter: reflecting on your personality. Self-reflecting is associated with activity in structures in the middle of the brain, in the frontal lobes (colored region on the right side of image on the left; and image on the right) and the cingulate cortex (large green-and-blue-colored region in the brain image on the left).

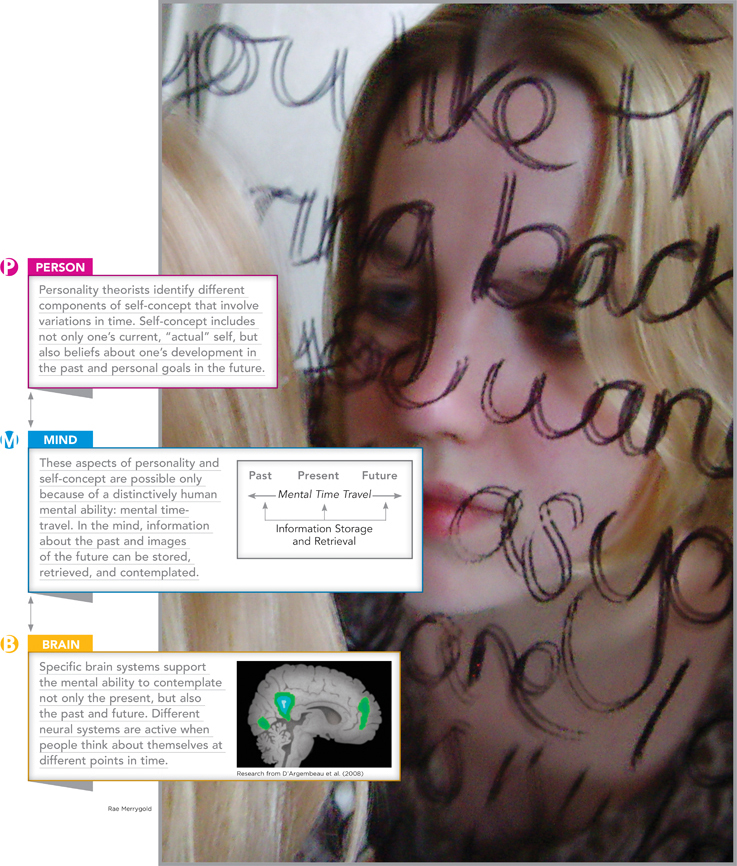

Twenty-first-century findings on personality and the brain deepen the understanding of human nature developed by twentieth-century psychologists. More generally, they show how contemporary psychology is integrative. Decades ago, research on self-concept, thinking processes, and the brain took part in disconnected sections of the field. Today, they are integrated. Findings from research with persons inform, and are enriched by, research on the brain (Figure 13.13).

figure 13.13 ARE THERE DIFFERENT COMPONENTS OF SELF-CONCEPT?

WHAT DO YOU KNOW?…

Question

30

Brain-imaging research indicates that different areas of the brain become active when people reflect on their past versus NubGAIb8ViDIUJXH selves. Such research is an example of how research on persons and on the brain kQsuOCtgePxcShy965l+YQ== or unites the field of psychology.

Does research on the brain support the idea that thinking can occur unconsciously?

Does research on the brain support the idea that thinking can occur unconsciously?

How have researchers studied the brain and people’s ability to think about themselves, or self-

How have researchers studied the brain and people’s ability to think about themselves, or self-