Chapter Summary

Chapter Summary

Section 1: What Is a Network Good?

Networks can consist of physical, virtual, or social networks.

Network goods are either produced within a network or depend on a network for their existence.

Every new user of a social media app increases the value of the network to every existing user and potential user, generating a network externality. When these external benefits are taken into account in the decision making by individuals and firms, they are referred to as network effects.

Section 2: Demand Curve for a Network Good

Networks typically involve high fixed costs and therefore are produced in large increments, such as adding a new wireless tower that can serve many customers. This leads to a network demand curve.

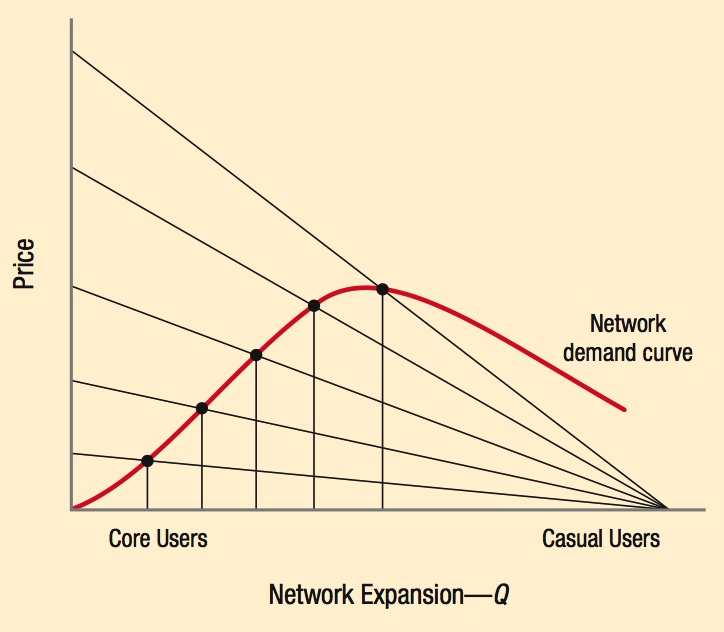

A network demand curve has upward-sloping and downward-sloping segments:

- Upward-sloping segment: Shown where the network effect exceeds the price effect, and typically occurs when a network is relatively new. Core users of network goods are the target in this part of the network demand curve.

- Downward-sloping segment: Shown where the price effect exceeds the network effect, and typically occurs once a network matures. In this part of the network demand curve, casual users join the network.

Deriving a Network Demand Curve

A network begins with a vertical short-run supply curve represents a fixed capacity (a maximum number of custom ers it can serve), and a corresponding demand curve. the network expands, the vertical supply curve shifts to right, and the corresponding demand curve increases to a network effect.

Two Opposing Effects on Prices in a Network

- Network effect: puts upward pressure on prices as output increases

- Price effect: puts downward pressure on prices as output increases

383

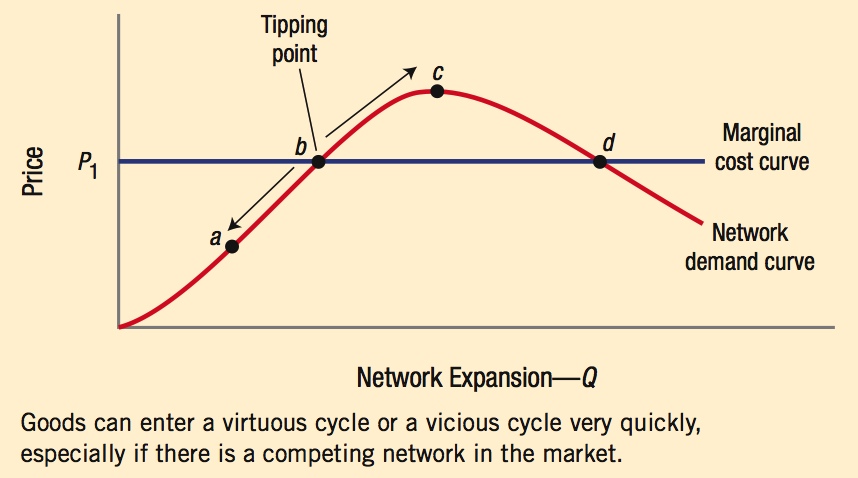

Section 3: Market Equilibrium for a Network Good

A network demand curve contains a tipping point (or critical mass), defined as the level of output that allows a network to expand further without significant effort by producers. When a tipping point is reached, the power of network effects propels the demand for a network good to a higher equilibrium point. This is referred to as a virtuous cycle. If a network good fails to reach its tipping point or falls below its tipping point, a vicious cycle can result as customers leave the network, further decreasing the value of the network to other users.

Section 4: Competition and Market Structure for Network Goods

Firms engage in a variety of marketing strategies to increase the likelihood of entering a virtuous cycle or to avoid entering a vicious cycle. The pressure to gain and retain customers is enhanced by the low marginal cost of production, which makes customers more valuable the longer they use a firm’s product.

Common strategies used by firms include:

- Teaser strategies

- Lock-in strategies

- Market segmentation by versioning (intertemporal pricing, peak-load pricing, and bundling)

Section 5: Should Network Goods Be Regulated?

Network effects allow successful firms to achieve significant market power, sometimes even a monopoly. To prevent firms from exploiting their market power, governments turn to regulation as a way to limit the abuse of market power.

Poor regulation can sometimes be worse than no regulation. Regulation is not always necessary when the costs of regulation exceed its benefits. The potential of competition itself can prevent monopolies from exploiting their market power.

384