THE ECONOMICS OF CLIMATE CHANGE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

360

Among the most significant economic issues facing the world today is the effect of human actions on the environment. There is scientific consensus that without a significant reduction in the production of greenhouse gases, which engulf the atmosphere and lead to global warming, irreversible damage to the climate, ecosystems, and coastlines will result. However, the course of action needed to address climate change deals with equity issues that are difficult to achieve consensus on.

cost-

Many individuals and corporations understand that natural resources are scarce and many do their parts by conserving water and energy resources, and recycling. Those who are more dedicated might choose public transportation over cars, install solar panels and other energy-

sustainable development The ability to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

The challenge with using cost-

Understanding Climate Change

Climate change refers to the gradual change in the Earth’s climate due to an increase in average temperatures resulting from both natural and human actions. It is largely irreversible, particularly in its effect on rising sea levels and on ecosystems. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the average temperature “from 1983 to 2012 was likely the warmest 30-

5 IPCC, 2014: Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp.

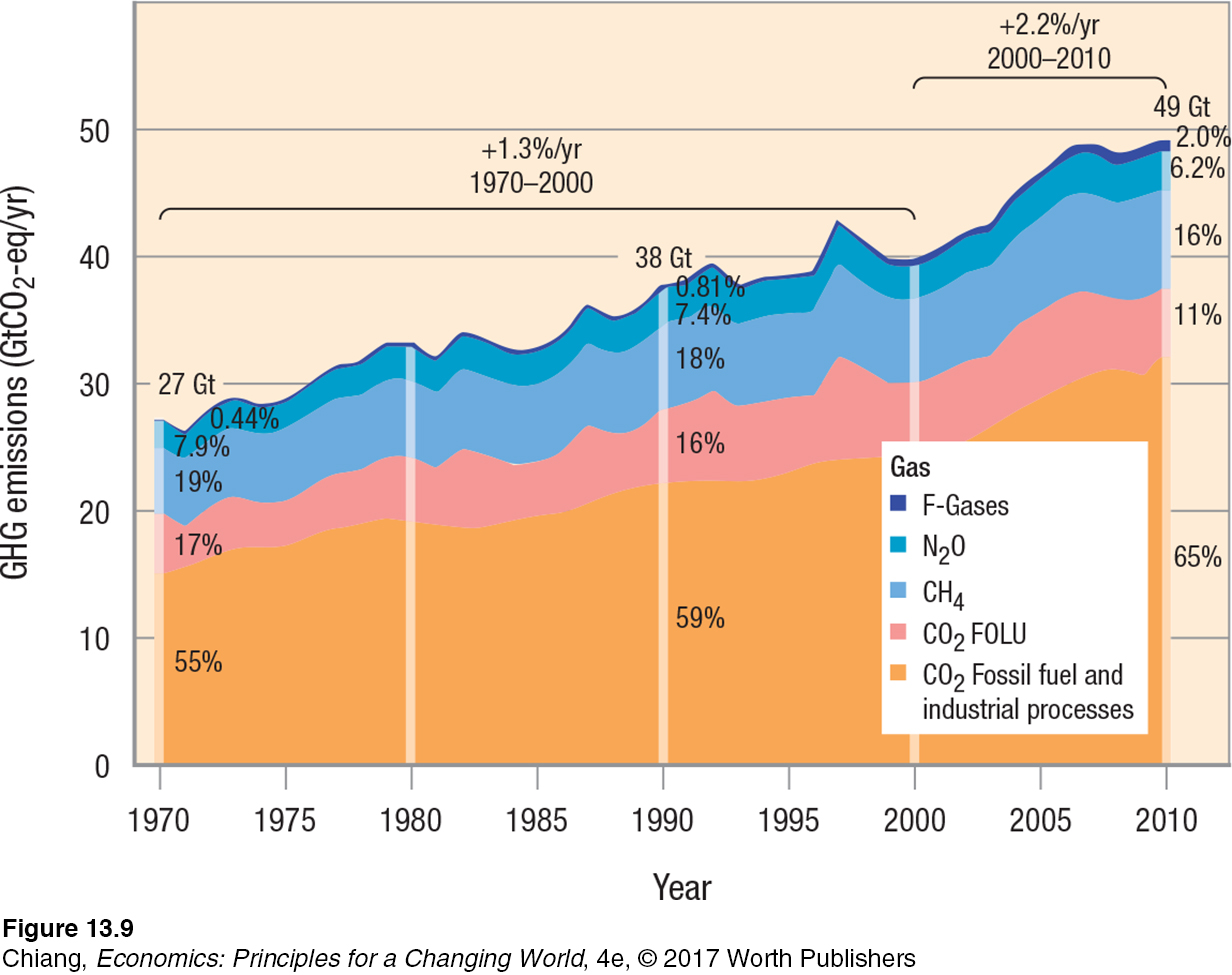

The Causes of Climate Change The primary causes of climate change are related to actions that emit greenhouse gases. Greenhouse gases created largely by human activities include carbon dioxide (CO2) from fossil fuel and industrial processes, carbon dioxide (CO2) from forestry and other land use (FOLU), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and fluorinated gases (F). Figure 9 shows both the global nominal rise in each of these greenhouse gases from 1970 to 2010, along with the percentage of overall greenhouse gases that each source represents.

Information obtained from the IPCC’s 2014 Climate Change Synthesis Report.

The largest portion of greenhouse gases is carbon dioxide, which is created by fossil fuel usage, industrial production, and deforestation. Fossil fuel usage includes the use of automobiles and airplanes, electricity and home heating fuels, and the production of products such as plastics and tires, and even everyday items such as ink pens, cosmetics, and toothpaste. Deforestation contributes to greenhouse gases because trees absorb carbon dioxide, and when they are cut down, the stored carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere.

361

Other forms of greenhouse gases include methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases. Methane is generated largely from livestock farming, landfills, and the production and use of fossil fuels. Nitrous oxide is produced on farms from the use of synthetic fertilizers along with fossil fuel usage. Finally, fluorinated gases are created in products such as modern refrigerators, air conditioners, and aerosol cans. Because fluorinated gases do not harm the ozone layer and are energy efficient, products that emit these gases have grown in popularity over the past decade, though they still contribute significantly to global warming.

The Consequences of Climate Change Today and in the Future A sense of urgency surrounds climate change because the state of climate change science has advanced to the point where scientists are able to put probability estimates on certain impacts of warming, some of which are catastrophic. The major impacts of climate change are in the areas of food security, water resources, ecosystems, extreme weather events, and rising sea levels. The IPCC summarizes the consequences of climate change by listing five key “reasons for concern,” as follows:

Unique and threatened systems: Many ecosystems are at risk, such as the diminishing Arctic sea ice and coral reefs, which leads to the extinction of species.

Extreme weather events: An increase in heat waves, heavy precipitation, and coastal flooding leads to major economic costs due to natural disasters and reductions in agricultural yields.

Distribution of impacts: The risks of climate change on disadvantaged people and communities are greater, especially those that depend on agricultural production.

Global aggregate impacts: Extensive biodiversity loss affects the global economy.

Large-

scale singular events: Melting ice sheets will lead to rising sea levels, causing significant loss of coastal lands.

The difficulty with addressing these effects is that unlike air or water pollution that can be seen today, climate change has a cumulative effect. In other words, this year’s CO2 adds to that from the past to raise concentrations in the future. Once CO2 levels reach a certain level, it may lead to extreme consequences that cannot be reversed. The global environment is essentially a common resource with many public goods aspects, and climate change is a huge global negative externality that extends long into the future.

The Challenges of Addressing Climate Change

362

Cleaning up pollution problems typically involves finding a level of abatement at which the marginal costs of abatement equal the marginal benefits. This can be achieved by taxing, assigning marketable permits, or using command and control policies to limit emissions. However, reducing global warming is not a short-

ELINOR OSTROM (1933–2012)

NOBEL PRIZE

When economists talk about common property resources, they typically discuss the “tragedy of the commons” and suggest a solution that involves privatization or central government takeover and management of the resource. Elinor Ostrom was awarded the 2009 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences for challenging this conventional wisdom by showing how user-

Born in 1933 during the depths of the Great Depression and completing her doctorate in political science in 1965, her dissertation looked at a case in which saltwater was seeping into western Los Angeles’s water basin. A group of individuals formed a water association to solve the problem by creating rules and injected water along the coast. Their efforts saved the basin. This experience led her to look at other common resource problems from a new perspective.

She used field studies and thousands of case studies by other social scientists along with game theory to determine how these informal organizations evolved and what conditions make them successful.

Her work has determined the requirements for sustainable user-

Ostrom’s insights and research have opened up an alternative to prevent the “tragedy of the commons.” Her work will be particularly important as nations begin working together to reduce the potential harm from global climate change, maybe our biggest common resource problem to date.

To further compound the problem, global climate change is a public good. Nobody can have less of it when someone has more (nonrivalry), and nobody can be excluded from its negative effects (nonexcludability). Technical innovations that help reduce CO2 emissions are costly to develop and are difficult to profit from due to the free rider problem, which means that efforts to combat climate change need to involve governments or organizations wishing to fix the problem for the greater good.

Even so, issues of equity arise when combating global warming. Why would one country invest in expensive clean energy processes when its neighbor continues to spew out emissions unhindered? Currently, nearly half of the world’s greenhouse gases are produced by China and the United States, which are the world’s two largest countries economically. Does that mean the United States and China should spend at least a proportionate amount reducing emissions? How well will that appeal to the citizens in each country? Such issues of equity will continue to be raised as increased global cooperation to combat climate change takes on increased urgency in the near future. For some corporations and countries, waiting is not an option, and efforts to promote sustainable development have increasingly become part of corporate sustainability missions and political platforms, respectively.

Promoting Sustainable Development

363

As the world’s population continues to grow and countries become wealthier, there is an enhanced effort to improve sustainable development to prevent future generations from suffering the consequences of actions taken today. Sustainable development involves a concerted effort by individuals, businesses, and governments to recognize the causes and impacts of climate change, and to take appropriate actions. Much of the technology needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions is already available today, and corporations and individuals play as much of a role as governments to keep global warming from worsening.

Corporate Social Responsibility

Nearly every company’s primary responsibility to shareholders is to maximize profits. However, promoting the image of the company as socially responsible has also become common. Take a glance at most major corporations’ Web sites and one will see a link to the company’s page on corporate social responsibility, highlighting its efforts to improve sustainable development and to provide educational opportunities and other economic programs for local communities.

But much like equity issues faced by countries, corporations face equity issues, too. Those in competitive industries must balance what they spend on their social responsibilities with their ability to generate sufficient monetary returns. Some companies have used social responsibility as a marketing strategy to promote market share. For example, both PepsiCo and Coca-

Individual Social Responsibility

One of the most common methods of reducing greenhouse gases by individuals is through recycling, with some communities even requiring households and businesses to recycle or face fines. Yet, the process of recycling itself uses energy, in addition to labor and other resources. A more effective means of promoting sustainability is to conserve resources. Examples of ways to improve conservation include the following actions:

Forgo paper financial statements and printed newspapers, magazines, and books—

for example, the use of online homework systems and digital textbooks has significantly reduced the use of paper. Use LED or compact fluorescent bulbs that use up to 90% less energy than traditional incandescent bulbs (many countries including the United States have passed laws phasing out incandescent bulbs).

Install smart temperature controls in homes that automatically reduce air conditioning and heating when the home is empty.

Plant trees or purchase carbon offsets to fund efforts to plant trees.

Drive less or drive fuel-

efficient or alternative fuel cars. Insulate walls and modernize windows.

Install solar panels.

Clearly, undertaking efforts to reduce our carbon footprint as a nation represents an insurance policy on the future. As new climate change information and technology becomes available, policies can be adjusted to reduce the potential costs in the future.

To that end, carbon dioxide emissions are frequently placed on political agendas. However, a slow economic recovery makes it harder to focus people’s attention on this issue. Moreover, environmental policies such as cap-

364

Globally, there has been increased effort in recent years to combat climate change, especially in the United States and China, the two biggest emitters of greenhouse gases. In 2015 the United States implemented the Clean Power Plan, setting new standards for reducing carbon emissions in power plants. Then in late 2015 the United Nations Climate Change Conference held in Paris led to the most comprehensive global accord passed to date. Signed by nearly 200 countries including the United States and China, the accord requires every country to enact a plan to reduce emissions, without mandating a specific level of reductions, which could conceivably cause political opposition within some countries. However, the agreement requires signing nations to reconvene every five years to report their progress, essentially creating global peer pressure to achieve its goals.

As with climate change, each of the examples described in this chapter dealt with market failure in which externalities, public goods, or shared resources lead the market away from a socially desirable output. Resolving a market failure generally requires some policy tool, such as the assignment of property rights, regulation, or the creation of market incentives to achieve the ideal outcome. However, determining which policy tool to use often leads to intense debate, making issues of market failure a challenge that societies and their policymakers will continue to face.

CHECKPOINT

THE ECONOMICS OF CLIMATE CHANGE AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT

Global climate change is a huge negative externality with an extremely long time horizon.

The public goods aspects of climate change make it a truly global problem.

Balancing the current generation’s costs and benefits against the potential harm to future generations raises difficult economic issues.

Actions taken today to reduce a potential future calamity are a form of insurance.

QUESTION: One of the most difficult aspects of climate change policy is determining how much individuals are willing to sacrifice today for a better environment in the future. What are some factors that may influence whether a person holds a high or low discount rate on the future with regard to environmental policy?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Many answers are valid. But any factor that causes one to place greater emphasis on the future would result in a lower discount rate. Such factors might include having children or grandchildren, a greater desire to preserve Earth’s natural beauty, having higher income or a business that relies on the availability of natural resources, or having empathy for future residents. Factors that might result in a high discount rate may include poverty, where emphasis is on improving one’s current economic well-