MODERN MONETARY POLICY

easy money, quantitative easing, or accommodative monetary policy Fed actions designed to increase excess reserves and the money supply to stimulate the economy (increase income and employment). See also expansionary monetary policy.

tight money or restrictive monetary policy Fed actions designed to decrease excess reserves and the money supply to shrink income and employment, usually to fight inflation. See also contractionary monetary policy.

When the Fed engages in expansionary monetary policy, it is buying bonds using money it creates by adding to the existing bank reserves deposited at the Fed. Other terms used to describe this process include easy money, quantitative easing, and accommodative monetary policy. It is designed to increase excess reserves and the money supply, and ultimately reduce interest rates to stimulate the economy and expand income and employment. The opposite of an expansionary policy is contractionary monetary policy, also referred to as tight money or restrictive monetary policy. Tight money policies are designed to shrink income and employment, usually in the interest of fighting inflation. The Fed brings about tight monetary policy by selling bonds, thereby pulling reserves from the financial system.

651

The Federal Reserve Act gives the Board of Governors significant discretion over conducting monetary policy. It sets goals, but leaves it up to the discretion of the Board of Governors how best to reach these objectives. As we have seen, the Fed attempts to frame monetary policy to keep inflation low over the long run, but also to maintain enough flexibility to respond in the short run to demand and supply shocks.

Rules Versus Discretion

monetary rule Keeps the growth of money stocks such as M1 or M2 on a steady path, following the equation of exchange (or quantity theory), to set a long-

The complexities of monetary policy, especially in dealing with a supply shock, have led some economists, most notably Milton Friedman, to call for a monetary rule to guide monetary policymakers. Other economists argue that modern economies are too complex to be managed by a few simple rules. Constantly changing institutions, economic behaviors, and technologies means that some discretion, and perhaps even complete discretion, are essential for policymakers. Also, if policymakers could use a simple and efficient rule on which to base successful monetary policy, they would have enough incentive to adopt it voluntarily, because it would guarantee success and their job would be much easier.

Milton Friedman argued that variations in monetary growth were a major source of instability in the economy. To counter this problem, which is compounded by the long and variable lags in discretionary monetary policy, Friedman advocated the adoption of monetary growth rules. Specifically, he proposed increasing the money supply by a set percentage every year, at a level consistent with long-

Friedman and other monetarists, like the classical economists before them, believed the economy to be inherently stable. If a demand shock is small or temporary, a monetary growth rule will probably function well enough. But if the shock is large or persistent, as was the case during the 2007–

In some cases, a monetary rule keeps policymakers from making things worse by preventing them from taking imprudent actions. Yet, the monetary rule also prevents policymakers from aiding the economy when a policy change is needed, as was the case in the 1970s when the Fed’s practice of setting a fixed rate for money supply growth wasn’t considered successful.

inflation targeting The central bank sets a target on the inflation rate (usually around 2% per year) and adjusts monetary policy to keep inflation near that target.

The alternative to setting money growth rules that modern monetary authorities around the world have tried is the simple rule of inflation targeting, which sets targets on the inflation rate, usually around 2% per year. If inflation (or the forecasted rate of inflation) exceeds the target, contractionary policy is employed; if inflation falls below the target, expansionary policy is used. Inflation targeting has the virtue of explicitly iterating that the long-

But while inflation targeting may work well to combat negative demand shocks, the same is not true when a negative supply shock occurs. Inflation targeting means that contractionary monetary policy should be used to reduce the inflation spiral. But contractionary policy would deepen the recession, and in reality, few monetary authorities would stick to an inflation-

The Federal Funds Target and the Taylor Rule

Taylor rule A rule for the federal funds target that suggests the target is equal to 2% + Current Inflation Rate + 1/2(Inflation Gap) + 1/2(Output Gap).

If not monetary targeting or inflation targeting, what other rule can the Fed use? We know that the Fed alters the federal funds rate as its primary monetary policy instrument. Under what circumstances will the Fed change its federal funds target? The Fed is concerned with two major factors: preventing inflation and preventing and moderating recessions. Professor John Taylor of Stanford University studied the Fed and how it makes decisions and he empirically found that the Fed tended to follow a general rule that has become known as the Taylor rule for federal funds targeting:

652

Federal Funds Target Rate = 2 + Current Inflation Rate + 1/2(Inflation Gap) + 1/2(Output Gap)

The Fed’s inflation target is typically 2%, the inflation gap is the current inflation rate minus the Fed’s inflation target, and the output gap is current GDP minus potential GDP1. If the Fed tries to target inflation around 2%, the current inflation rate is 4%, and output is 3% below potential GDP, then the target federal funds rate according to the Taylor rule is

1 The original Taylor rule used logarithms to measure the output gap. For simplicity, we use the percentage difference between current and potential GDP.

FFTarget = 2 + 4 + 1/2(4 − 2) + 1/2(−3)

= 2 + 4 + 1/2(2) + 1/2(−3)

= 2 + 4 + 1 − 1.5

= 5.5%

Notice that the high rate of inflation (4%) drives the federal funds target rate upward, while the fact that the economy is below its potential reduces the rate. If the economy were operating at its potential, the federal funds target would be 7%, because the Fed would not be worried about a recession and would be focused on controlling inflation.

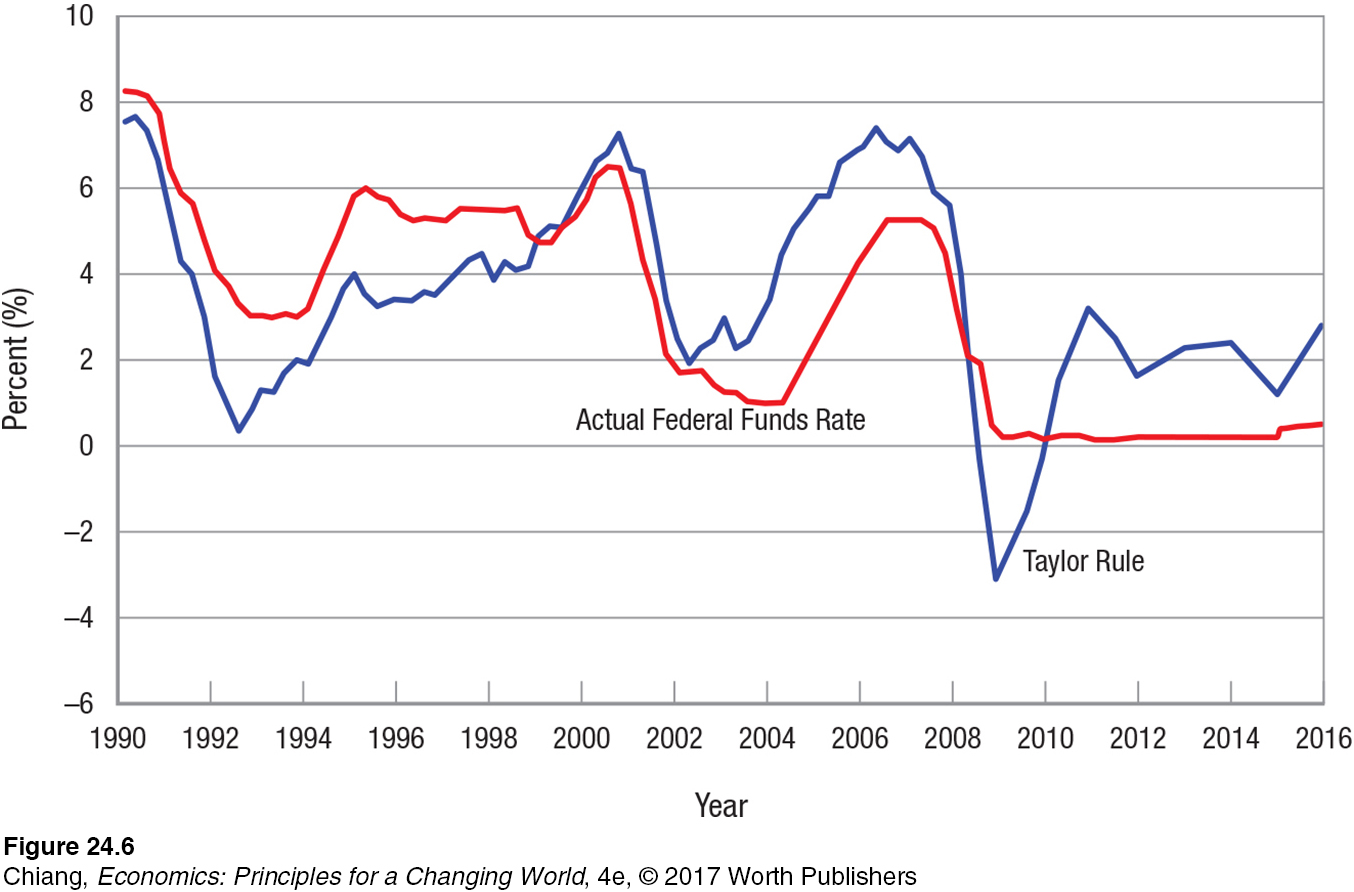

Figure 6 shows how closely the Taylor rule tracks the actual federal funds rate. Some economists have blamed the large spread between the two rates during the period between 2003 and 2007 for the housing boom that precipitated the financial crisis in 2008. They argue that the extremely low interest rates fueled the housing boom.

More important, what the Taylor rule tells us is that when the Fed meets to change the federal funds target rate, the two most important factors are whether inflation is different from the Fed’s target (typically 2%) and whether output varies from potential GDP. If output is below its potential, a recession threatens and the Fed will lower its target, and vice versa when output exceeds potential and inflation threatens to exceed the Fed’s target.

A Recap of the Fed’s Policy Tools

653

Now is a good time to summarize the monetary policy actions that the Fed can take to achieve its twin goals of price stability and full employment.

When output exceeds potential output (Q > Qf), firms are operating above their capacities and costs will rise, adding an inflationary threat that the Fed wants to avoid. Therefore, the Fed would increase the real interest rate to cool the economy. When output is below potential (Q < Qf), the Fed’s goal is to drive the economy back to its potential and avoid a recession along with the losses associated with an economy below full employment. The Fed does this by lowering the real interest rate. This reflects the Fed’s desire to fight recession when output is below full employment and fight inflation when output exceeds its potential.

Today, monetary authorities set a target interest rate and then use open market operations to adjust reserves and keep the federal funds rate near this level. The Fed’s interest target is the level that will keep the economy near potential GDP and/or keep inflationary pressures in check. When GDP is below its potential and a recession threatens the economy, the Fed uses expansionary policy to lower interest rates, expanding investment, consumption, and exports. When output is above potential GDP and inflation threatens, the Fed uses a higher interest rate target to slow the economy and reduce inflationary pressure.

Raising interest rates is never a politically popular act, but the Fed will be forced to balance future economic growth against rising inflationary expectations. As former Fed Chair William McChesney Martin said, “The job of a good central banker is to take away the punchbowl just as the party gets going.”

Transparency and the Federal Reserve

How does the Fed convey information about its actions, and why is this important? For many years, decisions were made in secrecy, and often they were executed in secrecy. The public did not know that monetary policy was being changed. Because monetary policy affects the economy, the Fed’s secrecy stimulated much speculation in financial markets about current and future Fed actions. Uncertainty often led to various counterproductive actions by people guessing incorrectly. These activities were highly inefficient.

When Alan Greenspan became head of the Fed in 1987, this policy of secrecy started to change. By 1994 the Fed released a policy statement each time it changed interest rates, and by 1998 it included a “tilt” statement forecasting what would probably happen in the next month or two. By 2000 the FOMC released a statement after each of its eight meetings per year even if policy remained the same. As the chapter opener describes, the FOMC statement is now one of the most anticipated pieces of economic news.

This new openness has come about because the Fed recognized that monetary policy is mitigated when financial actors take counterproductive actions when they are uncertain about what the Fed will do. In the words of William Poole, former president of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis,

Explaining a policy action—

2 William Poole, “Fed Transparency: How, Not Whether,” The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Review, November/December 2003, p. 5.

654

ISSUE

The Record of the Fed’s Performance

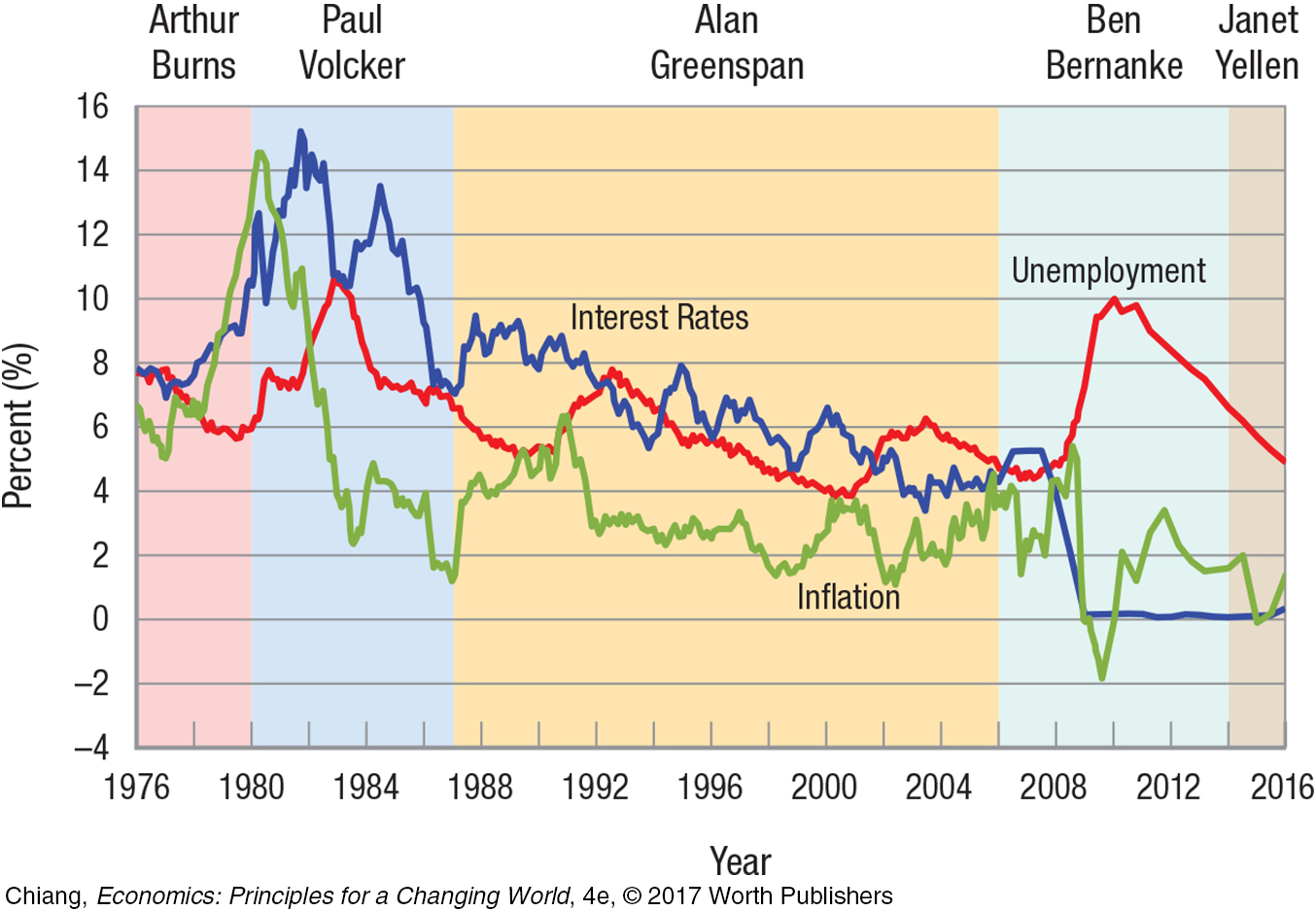

Determining how to measure the impact of Federal Reserve policy on our huge, complex economy is not easy. The figure shows how three variables—

*Technically, there were six Fed Chairs over this period. However, G. William Miller’s tenure lasted just over a year from 1978 to 1979, and therefore is not included in this graph.

Before 1980, when Arthur Burns headed the Fed, inflation was rising. An oil supply shock in 1973 was met with accommodative monetary policy and aggregate demand expanded.

The economy was hit with a second oil price shock in the late 1970s. By the early 1980s, inflation rose to double digits, peaking at over 14% in 1980. Paul Volcker, the head of the Fed at that time, tightened monetary policy to induce a recession (1981–

During the 1990s, the Alan Greenspan Fed alternated between encouraging output growth (mid-

The problems stemming from the housing collapse and financial crisis became a challenge for Fed Chair Ben Bernanke. In 2008 the Fed under Bernanke lowered the fed funds rate to almost 0%. In addition, the Bernanke Fed continued to expand the monetary base by purchasing long-

Fed transparency helps the public understand why it is taking certain actions. This helps the market understand what the Fed does in certain circumstances, and what the Fed is likely to do in similar situations in the future. The Fed’s “tilt” comment after each meeting provides a summary of the Fed’s outlook on the economy and information on the target federal funds rate. Transparency helps the Fed implement its monetary policy.

Until a decade ago, the performance of monetary authorities illustrated how effective discretionary monetary policy could be. Price stability was remarkable, unemployment and output levels were near full employment levels, interest rates were kept low, and economic growth was solid.

The global financial crisis and recovery over the past decade tested the limits of central banks in preventing economic catastrophe. On the one hand, some economists such as Janet Yellen (often referred to as “doves”) argue that greater Fed action is needed in times of economic hardship, while others (“hawks”) warn against the inflationary effects of too much monetary policy action. The concluding section of this chapter looks at the actions of the Fed and the European Central Bank in stemming the economic effects from a crisis, and how economic “doves” have gained significant influence in the way monetary policy has been implemented.

655

CHECKPOINT

MODERN MONETARY POLICY

In the past, monetary targeting was used to control the rate of growth of the money supply. Later, an alternative approach of inflation targeting, targeting the inflation rate to around 2%, became more prevalent.

The Fed sets a target federal funds rate and then uses open market operations to adjust reserves and keep the federal funds rate near this level.

The Taylor rule is a general rule that ties the federal funds rate target to the inflation gap and the output gap for the economy, and has done a good job in estimating the actual federal funds rate target set by the Fed.

When inflation rises, the Fed uses contractionary monetary policy to increase the federal funds rate to slow the economy. When the economy drifts into a recession and inflationary pressures fall, the Fed does the opposite and reduces the federal funds rate, giving the economy a boost.

Fed transparency helps us to understand why the Fed makes particular decisions and also what the Fed will probably do in similar circumstances in the future.

QUESTION: After years of quantitative easing, many worry that inflation will eventually become a problem. Why should bond investors sell when the Fed or other central bankers decide that inflation is a growing problem?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

When the Fed begins to view inflation as a growing problem, it usually means that some form of contractionary monetary policy is to follow. This typically means that interest rates will rise and, most important for bond investors, bond prices will fall and bondholders will incur capital losses.