LABOR UNIONS AND COLLECTIVE BARGAINING

Suppose Max, an engineer and project coordinator, has worked at a large construction company for eight years. He had been training new employees on various aspects of cost estimating and job specification, and he noticed that these new people were being hired at salaries approaching his own. He requested a raise several times, but was essentially ignored. Exasperated, he refused to go to work one day, informing his boss that he would not return without a raise. He did not quit; he simply staged a walkout and refused to return until given a raise. In other words, Max staged a one-

296

This story is unique in that one-

This section looks at the role unions play in our economy, their history, and their effects on the labor market. We show how unions create wage differentials that work against the assumptions of the competitive labor market in which all workers earn the same wage. We will see that although unions have been successful in some industries, their influence has faded in other industries.

Types of Unions

Labor unions are legal associations of employees that bargain with employers over terms and conditions of work, including wages, benefits, and working conditions. They use strikes and threats of strikes, as well as other tactics, to try to achieve their goals.

Unions are usually defined by industry, or by craft or occupation. A craft union represents members of a specific craft or occupation, such as air traffic controllers (PATCO), truck drivers (Teamsters), and teachers (AFT). An industrial union represents all workers employed in a specific industry. Examples include auto workers (UAW) and public employees (AFSCME).

Benefits and Costs of Union Membership

Without a union, each individual employee would have to bargain with management over his or her own wages, benefits, and working conditions. Unions bring collective power to this bargaining arrangement. The source of this power is ultimately the willingness of the union to strike if no agreement is reached during negotiations. Collective bargaining often leads to a more equitable pay schedule than individual negotiation. It also provides workers with greater job security by protecting them against arbitrary or vindictive decisions by management.

Union membership, like everything else, has its price. First, union members must pay monthly dues. Then, if negotiations break down and a strike is called, wages are lost and the possibility exists, however remote, that management will refuse to settle with the union and replace the entire workforce. Finally, union workers must give up some individual flexibility because their work rules are more rigid.

Brief History of American Unionism

Labor unions date to the late 18th century in England. In the United States, public attitudes toward unions were highly unfavorable until the Great Depression. In the early part of the 20th century, employers could easily secure legal injunctions against union organization by arguing that unions behaved like monopolies, in violation of antitrust laws. Employers often required employees to sign enforceable yellow dog contracts, in which they agreed not to join a union as a condition of employment. As a result, unions represented only 7% of workers in 1930.

With the onset of the Great Depression, attitudes about collective bargaining changed. In 1932 Congress passed the Norris-

297

closed shop Workers must belong to the union before they can be hired.

union shop Nonunion hires must join the union within a specified period of time.

agency shop Employees are not required to join the union, but must pay dues to compensate the union for its services.

right-

The consequence of higher union participation is the increased likelihood of work stoppages, or strikes, which became more common. This resulted in some pushback, however, as many people believed unions had become too powerful. Because of this swing in public opinion, in 1947, Congress passed the Taft-

From the 1950s to the 1970s, union membership was steady. The right to collective bargaining was extended to federal workers in 1962, though public employees are not permitted to strike, but rather must submit to binding arbitration to resolve disputes. Since the 1970s, however, union membership has declined, partly due to political reasons but also due to changes in the economic landscape. Another aspect of the Taft-

ISSUE

The End of the Road for Pensions: Unions Fight to Preserve Promises Made to Retirees

Pensions were once one of the most valuable benefits of working for a company or the government. The longer an employee stays with a company or government agency, the greater the monthly pension one would expect to receive upon retirement (usually at age 55 or 65) for the rest of one’s life. For employees who devoted decades of their life to a company, it was common to receive a monthly pension close to or even equal to what they earned while working. Unions played an important role in preserving pension plans for their members.

Times have changed. As the average life expectancy of retirees increased, so has the cost of funding pensions. Moreover, the cost of pensions is an unpredictable expense, because it depends on an unknown period of payments until the recipient passes away. Therefore, as union membership declined in the private sector, many companies switched from offering pension plans to defined contribution plans, such as a 401K in which a company deposits funds into an employee’s retirement account throughout his or her working career. The benefit of 401K plans to companies is that once an employee retires, they are no longer liable for any additional expense. The downside, as unions are quick to point out, is that this reduces the financial security of retirees because the money they save can run out.

Today, the fight over pensions largely deals with public sector employees, including government agency workers and public school teachers, who until recently still had the ability to choose generous state-

The challenge faced by unions to protect the pension plans earned by workers who have devoted their lives to a company or the government will likely be difficult for another generation until all existing pension recipients’ obligations are fulfilled. For those entering the workforce today, pensions are a relic of a past era. Workers today must proactively plan and save to ensure a comfortable retirement.

298

Union Versus Nonunion Wage Differentials

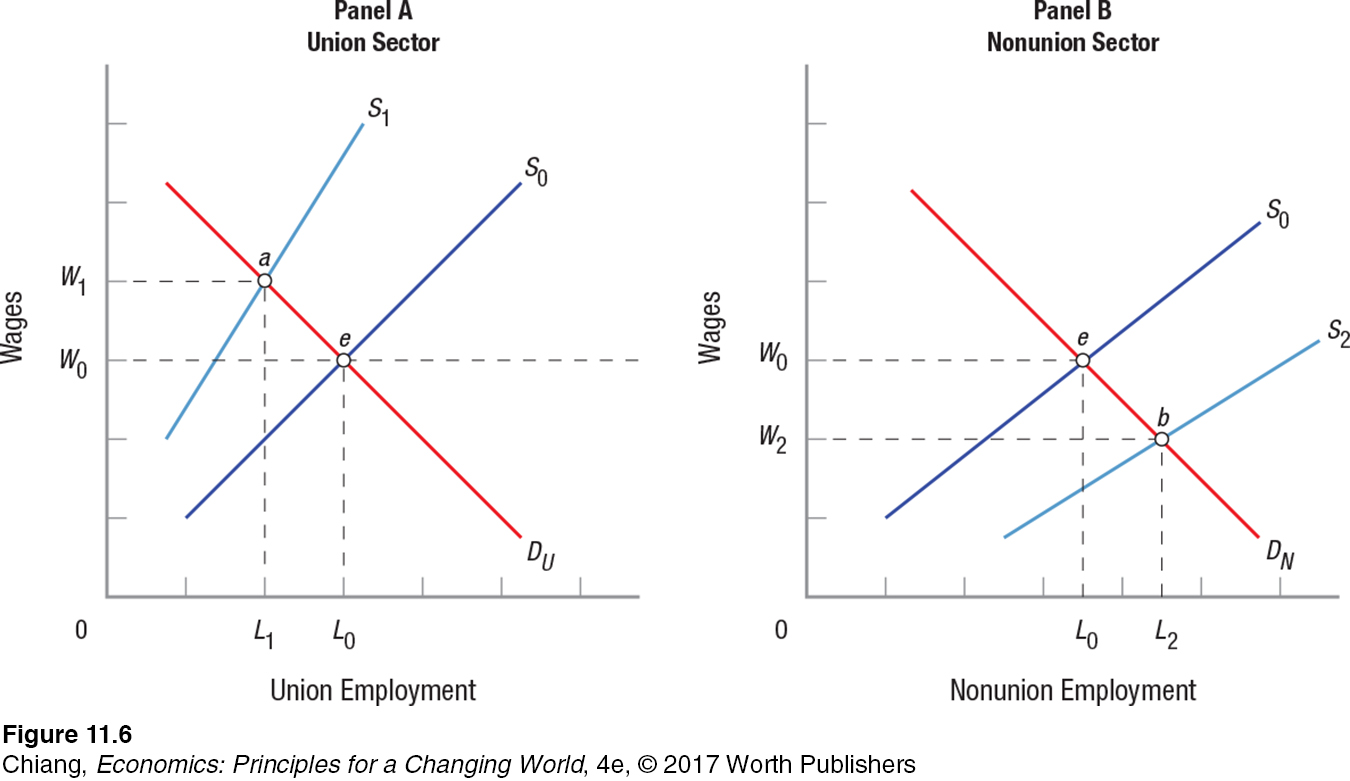

Why join a union? The primary benefit to unionization should be higher wages, given the union’s collective bargaining power. The general theoretical argument for union−nonunion wage differentials is illustrated in Figure 6.

This figure shows how unions are able to increase the wages in their sectors by restricting entry into union jobs. The markets for both unionized and nonunion labor begin at equilibrium, at point e in both panels of Figure 6. Thus, union and nonunion wages are initially equal, at W0. If the union successfully restricts supply to S1 in panel A, union wages will rise to W1, but employment will fall to L1 (point a). The remaining workers, however, have no choice but to move over to the nonunion sector represented in panel B, thus shifting its supply to S2. Equilibrium in the nonunion sector moves to point b, where more workers (L2) are employed at lower wages (W2). The resulting wage differential, W1 − W2, is caused by successful collective bargaining in the union sector. Notice that this analysis is substantially the same as that for discrimination in the segmented labor force described in Figure 5 earlier.

299

Union−nonunion wage differentials vary by the union, occupation, industry, and historical period. In general, average union wages are 10% to 20% higher than the average nonunion wage. Union wage effects are most pronounced among blue-

CHECKPOINT

LABOR UNIONS AND COLLECTIVE BARGAINING

Unions are typically organized around a craft or an industry.

Unions and the managers of firms must bargain “in good faith.”

In a closed shop, only union members are hired. This was outlawed by the Taft-

Hartley Act. In a union shop, nonunion workers can be hired, but they must join the union within a specified period. An agency shop permits both union and nonunion workers, but the nonunion workers must pay union dues. Union wage differentials are between 10% and 20% higher.

QUESTION: Union negotiations always seem to run up against a “strike deadline.” Are there incentives for both sides to put off a settlement until the very last moment?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Both sides work hard to get the best bargain for their constituents. There are incentives to continue negotiations up to the last moment to get the most and to appear to be driving a hard bargain. Strikes involve costs, and both sides use the threat of imposing these costs as a bargaining chip.