FIRMS, PROFITS, AND ECONOMIC COSTS

170

In the opening story, Toyota and Tesla had to make a decision about producing a product. Who makes such decisions? It’s the firms and entrepreneurs who choose to take on the risk and effort to launch a new product. They are motivated by the profits that can be earned if the investment proves successful. But how do we measure profits?

This section highlights the important role that firms and entrepreneurs play in producing the goods and services we enjoy as consumers. No matter how the organizational structure is set up, firms and entrepreneurs hold profits as their motivating force. To achieve profits, both revenues and costs must be considered. As we will see, profits can be measured using an accounting approach or an economics approach. These approaches differ in the way costs are measured.

Firms

firm An economic institution that transforms resources (factors of production) into outputs.

A firm is an economic institution that transforms inputs, or factors of production, into outputs, or products. Most firms begin as family enterprises or small partnerships. When successful, these firms can evolve into corporations of considerable size.

In the process of producing goods and services, firms must make numerous decisions. First, they have to determine a market need. Then, most broadly, firms must decide what quantity of output to produce, how to produce it, and what inputs to employ. The latter two decisions depend on the production technology that the firm selects.

Any given product can typically be produced in a wide variety of ways. Some businesses, like McDonald’s franchises and Dunkin’ Donuts shops, use considerable amounts of capital equipment, whereas others, such as T-

Entrepreneurs

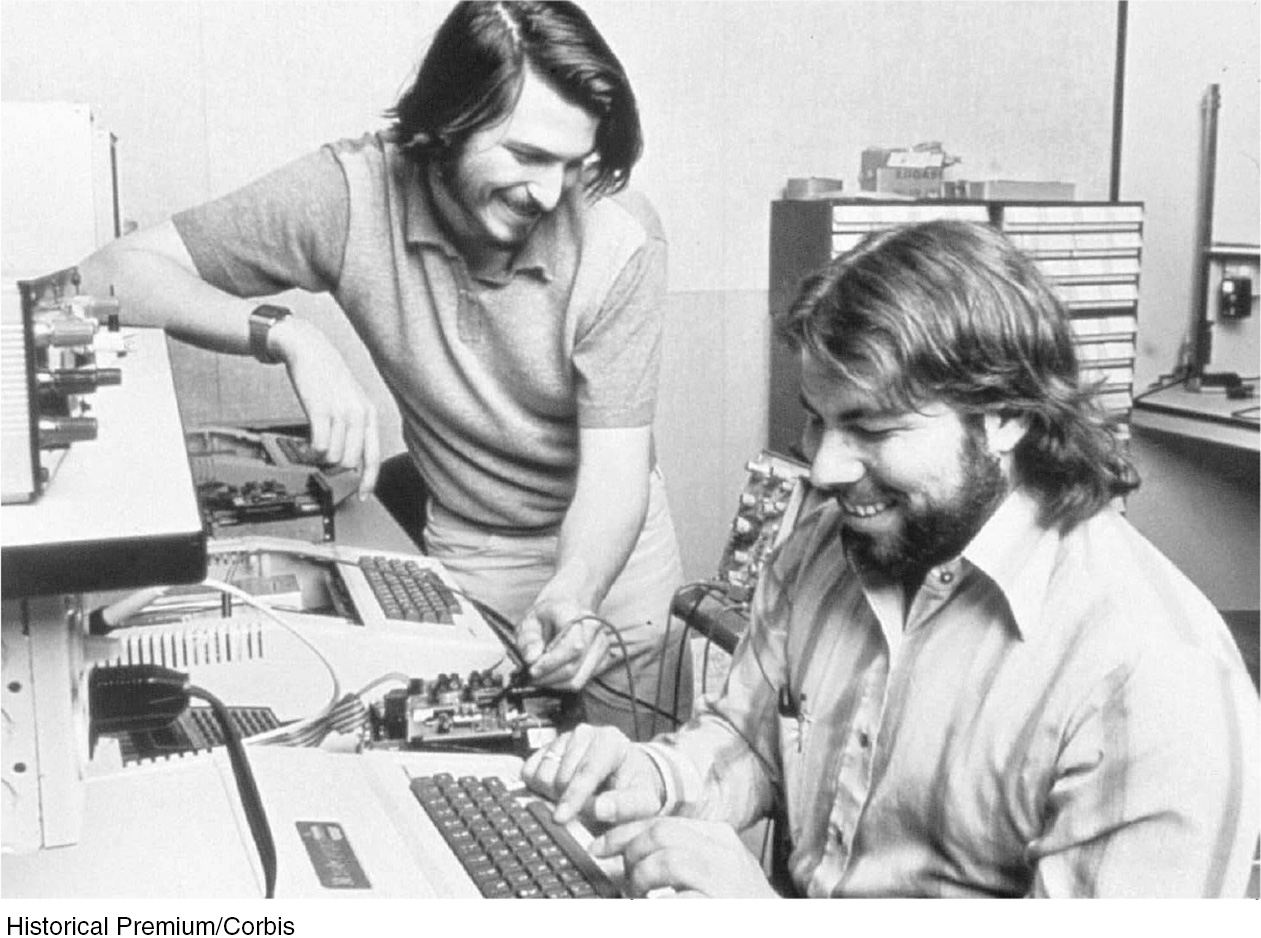

If a product or service is to be provided to the market, someone must first assume the risk of raising the required capital, assembling workers and raw materials, producing the product, and, finally, offering it for sale. Markets provide incentives and signals, but it is entrepreneurs who provide products and services by taking risks in the hopes of earning profits.

In the United States, 9.7% of people ages 18 to 64 classify themselves as entrepreneurs. This means they are running start-

1 Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, “2014 Global Report,” 2015.

Entrepreneurs can be divided into three basic business structures: sole proprietorships (one owner), partnerships (two or more owners), and corporations (many stockholders). The United States has more than 25 million businesses, over 70% of them sole proprietorships or small businesses. Only 20% of U.S. businesses are corporations. Nevertheless, corporations sell nearly 90% of all products and services in the United States. Likewise, around the world, the corporate form of business has become the dominant form. To see why, we must first take a brief look at the advantages and disadvantages of each business structure.

sole proprietorship A type of business structure composed of a single owner who supervises and manages the business and is subject to unlimited liability.

Sole Proprietors The sole proprietorship represents the most basic form of business organization. A sole proprietorship is composed of one owner, who usually supervises the business operation. Local restaurants, dry cleaning businesses, and auto repair shops are often sole proprietorships. A sole proprietorship is easy to establish and manage, having much less paperwork associated with it than other forms of business organization. But the sole proprietorship has disadvantages. Single owners are often limited in their ability to raise capital. In many instances, all management responsibilities fall on this single individual. And most important, the personal assets of the owner are subject to unlimited liability. If you own a pizza shop as a sole proprietor and someone slips on the floor, he or she can sue you and you could lose your house and your life savings if you do not have sufficient insurance coverage.

171

partnership Similar to a sole proprietorship, but involves more than one owner who share the management of the business. Partnerships are also subject to unlimited liability.

Partnerships Partnerships are similar to sole proprietorships except that they have more than one owner. Establishing a partnership usually requires signing a legal partnership document. Partnerships find it easier to raise capital and spread around the management responsibilities. Like sole proprietors, however, partners are subject to unlimited liability, not only for their share of the business, but for the entire business. If your partner takes off for Bermuda, you are left to pay all the bills, even those your partner incurred. The death of one partner dissolves a partnership, unless other arrangements have been made ahead of time. In any case, the death of a partner often creates problems for the continuity of the business.

corporation A business structure that has most of the legal rights of individuals, and in addition, can issue stock to raise capital. Stockholders’ liability is limited to the value of their stock.

Corporations The corporation is the premier form of business organization in most of the world. In 2015 roughly 6 million U.S. corporations sold over $29 trillion worth of goods and services worldwide. This is a remarkable statistic when you consider that the country’s 20 million sole proprietorships had sales totaling just over $1.5 trillion. Clearly, corporations are structured in a way that enhances growth and efficiency.

Corporations have most of the legal rights of individuals; in addition, they are able to issue stock to raise capital, and most significant, the liability of individual owners (i.e., stockholders) is limited to the amount they have invested in (or paid for) the stock. This is what distinguishes corporations from the other forms of business organization: the ability to raise large amounts of capital because of limited liability.

Some scholars argue that corporations are the greatest engines of economic prosperity ever known.2 Daniel Akst writes:

2 John Micklethwait and Adrian Wooldridge, The Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea (New York: Modern Library), 2003.

When I worked for a big company, there was a miracle in the office every couple of weeks, just like clockwork. It happened every payday, when sizable checks were distributed to a small army of employees who also enjoyed health and retirement benefits. Few of us could have made as much on our own, and somehow there was always money left over for the shareholders as well.3

3 Daniel Akst, “Where Those Paychecks Come From,” Wall Street Journal, February 3, 2004.

Without the corporate umbrella, most of the jobs we hold would not exist; most of the products we use would not have been invented; and our standard of living would be a fraction of what it is today.

What is it that motivates business owners of all types to take on the risks of creating a product? Profits.

Profits

profit Equal to the difference between total revenue and total cost.

Entrepreneurs and firms employ resources and turn out products with the goal of making profits. This is not to say that firms put profit above all else (i.e., that they would do something immoral or socially irresponsible to increase profits), but instead that firms do not intentionally make decisions that would knowingly result in lower profit. Profit is the difference between total revenue and total cost.

total revenue Equal to price per unit times quantity sold.

total cost The sum of all costs to run a business. To an economist, this includes out-

Total revenue is the amount of money a firm receives from the sales of its products. It is equal to the price per unit times the number of units sold (TR = p × q). Note that we use lowercase p and q when we are dealing with an individual firm and uppercase letters when describing a market. Total cost includes both out-

ISSUE

172

The Vast World of Corporate Offshoring and Profits

Most Americans are aware of the fact that corporations, particularly in manufacturing industries, often relocate factories to developing countries to take advantage of lower costs for labor and raw materials (in a process called offshoring) and to gain access to emerging markets for their products. Yet, another incentive exists for why companies choose to place important offices, even headquarters, abroad, and that is to avoid U.S. regulations and taxes.

One common example of corporate offshoring occurs in the cruise ship industry. Despite many cruise ships starting and ending trips at U.S. ports, virtually all large cruise vessels are registered outside of the United States, allowing cruise lines to circumvent, for example, U.S. labor laws (ever wonder how a room steward is able to legally work seven days a week, day and night, at less than minimum wage?).

The more egregious examples of offshoring occur when companies relocate headquarters to certain countries to take advantage of lower tax rates. And by relocating, this often does not mean moving to a shiny new skyscraper in a major European or Asian capital. On the contrary, it sometimes involves merely having a mailbox in an obscure town or island serving as the headquarters for a multimillion dollar enterprise.

Recent media attention exposing the abuse of corporate offshoring has led to new reforms being proposed in the United States and the European Union. Various proposed legislation, such as the Stop Tax Haven Abuse Act, aimed at curbing the use of corporate offshoring when the sole purpose is to avoid taxes (as opposed to traditional offshoring to take advantage of less expensive inputs of production). But like all new policies, tradeoffs exist, as companies affected by the new legislation claim such rules would reduce competition and raise consumer prices. The costs and benefits of any new policy are likely to be debated extensively before becoming law.

Economists explicitly assume that firms proceed rationally and have the maximization of profits as their primary objective. Alternative behavioral assumptions for firms have been tested, including sales maximization, various goals for market share, and customer satisfaction. Although these more complex assumptions for firm behavior often predict different outcomes, economists have not been persuaded that any of them yield results superior to those of the profit maximization approach. Profit maximization has stood the test of time, and thus we will assume it is the primary economic goal of firms.

Economic Costs

economic costs The sum of explicit (out-

When economists talk about “profit,” they take into account business costs from the opportunity cost perspective. They separate costs into explicit costs, or out-

explicit costs Those expenses paid directly to another economic entity, including wages, lease payments, taxes, and utilities.

Explicit costs are those expenses paid directly to some other economic entity. These costs include wages, lease payments, expenditures for raw materials, taxes, utilities, and so on. A company can easily determine its explicit costs by summing all of the payments it has made during the normal course of doing business.

implicit costs The opportunity costs of using resources that belong to the firm, including depreciation, depletion of business assets, and the opportunity cost of the firm’s capital employed in the business.

Implicit costs refer to all of the opportunity costs of using resources that belong to the firm. Recall that opportunity cost measures the value of the next best alternative use of resources, including that of time and capital. Implicit costs include depreciation, the depletion of business assets, and the opportunity cost of a firm’s capital.

In any business, some assets are depleted over time. Machines, cars, and office equipment depreciate with use and time. Finite oil or mineral deposits are depleted as they are mined or pumped. Even though firms do not actually pay any cash as these assets are worn down or used up, these costs nonetheless represent real expenses to the firm.

173

Another major component of implicit costs is the capital firms have invested. Even small firms incur large implicit costs from their capital investment. Small entrepreneurs, for example, must invest both their own capital and labor into their businesses. Such people could normally be working for someone else, so their “lost salary” must be treated as an implicit cost when determining the true profitability of their businesses. Similarly, any capital invested in a business enterprise could just as well be earning interest in a bank account or returning dividends and capital gains through the purchase and sale of stock in other enterprises. Though not directly paid out as expenses, these forgone earnings nonetheless represent implicit costs for the firm.

Economic and Normal Profits

The primary goal of any firm is to earn a profit. However, how the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) measures profit for tax purposes is different from how an economist determines profit. Suppose that after graduating, you decide to open a new billiards hall on campus. After a year, counting all the revenues and subtracting all explicit costs (costs that you actually pay out), you end up with a profit of $20,000. Is your business a success? The IRS certainly thinks so, as it will collect taxes on these profits. And you might brag to friends that you turned a profit in your first year. But then you start thinking of all the time you spent on the business and the missed opportunities, such as the $40,000 a year job offer you turned down, and the money you could have earned had you invested your savings in stocks or bonds rather than in your business. Now, your business doesn’t feel successful.

accounting profit The difference between total revenue and explicit costs. These are the profits that are taxed by the government.

economic profit Profit in excess of normal profits. These are profits in excess of both explicit and implicit costs.

normal profits The return on capital necessary to keep investors satisfied and keep capital in the business over the long run.

Economists include both explicit and implicit costs in their analysis of business profits. An accounting profit is calculated by including only explicit costs, while an economic profit is calculated using both explicit and implicit costs. Therefore, when a firm is earning economic profits, it is generating profits in excess of zero once implicit costs are factored in. This brings us to an important benchmark called normal profits, which occurs when economic profit equals zero. Economists refer to this level of profit as a normal rate of return on capital, a return just sufficient to keep investors satisfied and to keep capital in the business over the long run. If a firm’s rate of return on capital falls below this rate, investors will put their capital to use elsewhere.

Although earning zero economic profit might sound dismal, this simply means that the firm is earning the same profit it would have earned had it chosen its next best alternative use of its capital, which can be quite substantial in terms of accounting profit. For example, if Mark Zuckerberg left Facebook and opened a new business, his new business (assuming he uses the same amount of capital and labor) would have to earn billions of dollars a year just to achieve normal profits. Not bad for zero economic profit. In other words, any profit less than what would be earned at Facebook under his leadership would be considered an economic loss. A firm earning normal profits means that it is earning just enough to cover the opportunity cost of its capital. Therefore, a firm may be earning accounting profits as defined by the IRS for tax purposes, yet still be suffering economic losses, because taxable income does not reflect all implicit costs.

Let’s look at the difference between accounting profits and economic profits further in Table 1, using our example of the billiards hall. Suppose your annual total revenue is $120,000. After subtracting out-

Economists designate normal profits as economic profits equal to zero. To achieve normal profits, you would need to be just as well off operating the billiard hall as you would if you instead took another job and invested your savings elsewhere, which means earning $50,000 in accounting profits. Because you earned only $20,000 (or $30,000 less than the alternative), this results in an economic loss of $30,000. Normal profits are the profits necessary to keep a firm in business over the long run. This brings us to an important economic distinction, between the short run and the long run.

Short Run Versus Long Run

174

Although the short and the long run generally differ in their temporal spans, they are not defined in terms of time. Rather, economists define these periods by the ability of firms to adjust the quantities of various resources that they are employing.

short run A period of time over which at least one factor of production (resource) is fixed, or cannot be changed.

The short run is a period of time over which at least one factor of production is fixed, or cannot be changed. For the sake of simplicity, economists typically assume that plant capacity is fixed in the short run. Output from a fixed plant can still vary depending on how much labor the firm employs. Firms can, for instance, hire more people, have existing employees work overtime, or run additional shifts. For discussion purposes, we focus here on labor as the variable factor, but changes in the raw materials used can also result in output changes.

long run A period of time sufficient for firms to adjust all factors of production, including plant capacity.

The long run, conversely, is a period of time sufficient for a firm to adjust all factors of production, including plant capacity. Since all factors can be altered in the long run, existing firms can even close and leave the industry, and new firms can build new plants and enter the market.

In the short run, therefore, with plant capacity and the number of firms in an industry being fixed, output varies only as a result of changes in employment. In the long run, as plant capacity and other factors are made variable, the industry may grow or shrink as firms enter or leave the business, or some firms alter their plant capacity.

Because all industries are unique, the time required for long-

The important point to note from this section is that firms seek economic profits and determine profits by first calculating their costs. These costs may differ over the short run versus the long run. Therefore, we look first at production basics, then consider costs in both the short run and the long run.

175

CHECKPOINT

FIRMS, PROFITS, AND ECONOMIC COSTS

Firms are economic institutions that convert inputs (factors of production) into products and services.

Entrepreneurs provide goods and services to markets. Entrepreneurs can be organized into three basic business structures: sole proprietorships, partnerships, and corporations.

Corporations are the premier form of business organization because they give owners (shareholders) limited liability, unlike sole proprietorships and partnerships.

Profit is the difference between total revenues and total costs.

Explicit costs are those expenses, such as rent and the cost of raw materials, paid directly to some other economic entity. Implicit costs represent the opportunity costs of doing business, including depreciation and the firm’s capital costs.

Normal profits (or normal rates of return) are equal to zero economic profit. The firm is earning just enough to keep capital in the firm over the long run. Economic profits are those in excess of normal profits.

The short run is a period of time during which one factor of production (usually plant capacity) is fixed. In the long run, all factors can vary and the firm can enter or exit the industry.

QUESTION: Assume for a moment that you want to go into business for yourself and that you have a good idea. What are the pros and cons of setting up your company as a corporation as opposed to keeping it as a sole proprietorship?

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Setting up your firm as a corporation has its benefits and its costs. One benefit of a corporation is limited liability, which means that if your company fails, the company can declare bankruptcy without it affecting your personal assets or credit. Another benefit is the ability to raise capital by issuing bonds or stocks. The downside of setting up a corporation is that profits are potentially shared by many shareholders. Also, corporations involve much more paperwork (such as setting up the firm and filing tax returns) than a sole proprietorship, which is much easier to set up and manage.