MARKET STRUCTURE ANALYSIS

196

market structure analysis By observing a few industry characteristics such as number of firms in the industry or the level of barriers to entry, economists can use this information to predict pricing and output behavior of the firm in the industry.

To appreciate competitive markets, we need to look at competition within the full range of possible market structures. Economists use market structure analysis to categorize industries based on a few key characteristics. By knowing simple industry facts, economists can predict the behavior of firms in that industry in such areas as pricing and sales.

Following are the four factors defining the intensity of competition in an industry and a few questions to give you some sense of the issues behind each one of these factors.

Number of firms in the industry: Does the industry comprise many firms, each with limited or no ability to set the market price, such as local strawberry farms, or is it dominated by a large firm such as Apple that can influence price regardless of the number of other firms?

Nature of the industry’s product: Are we talking about a homogeneous product such as plain table salt, for which no consumer will pay a premium or are we considering leather handbags, which consumers may think vary greatly, in that some firms (Coach, Gucci) produce better goods than others?

Barriers to entry: Does the industry require low start-

up and maintenance costs such as found at a roadside fruit and vegetable stand, or is it a computer- chip business that may require $1 billion to build a new chip plant? Extent to which individual firms can control prices: Pharmaceutical companies can set prices for new medicines, at least for a period of time, because of patent protection. Farmers and copper producers have virtually no control and get their prices from world markets.

Possible market structures range from perfect competition, characterized by many firms, to monopoly, where an industry is made up of only one firm. These market structures will make more sense to you as we consider each one in the chapters ahead. Right now, use this list and the descriptions as reference points. You can always return here and put the discussion in context.

Primary Market Structures

197

The primary market structures economists have identified, along with their key characteristics, are as follows:

Perfect Competition

Many buyers and sellers

Homogeneous (standardized) products

No barriers to market entry or exit

No long-

run economic profit No control over price (no market power)

Monopolistic Competition

Many buyers and sellers

Differentiated products

Little to no barriers to market entry or exit

No long-

run economic profit Some control over price (limited market power)

Oligopoly

Fewer firms (such as the auto industry)

Mutually interdependent decisions

Substantial barriers to market entry

Potential for long-

run economic profit Shared market power and considerable control over price

Monopoly

One firm

No close substitutes for product

Nearly insuperable barriers to entry

Potential for long-

run economic profit Substantial market power and control over price

Putting off discussion of the other market structures for later chapters, we turn to an extended examination of the requirements for a perfectly competitive market. In the remainder of this chapter, we explore short-

Defining Perfectly Competitive Markets

perfect competition A market structure with many relatively small buyers and sellers who take the price as given, a standardized product, full information to both buyers and sellers, and no barriers to entry or exit.

The theory of perfect competition rests on the following assumptions:

Perfectly competitive markets have many buyers and sellers, each of them so small that none can individually influence product price.

Firms in the industry produce a homogeneous or standardized product.

Buyers and sellers have all the information about prices and product quality they need to make informed decisions.

198

Barriers to entry or exit are nonexistent; in the long run, new firms are free to enter the industry if doing so appears profitable, while firms are free to exit if they anticipate losses.

price taker Individual firms in perfectly competitive markets determine their prices from the market because they are so small they cannot influence market price. For this reason, perfectly competitive firms are price takers and can sell all the output they produce at market-

One implication of these assumptions is that perfectly competitive firms are price takers. Market prices are determined by market forces beyond the control of individual firms. That is, firms must take what they can get for their products. Paper for copy machines, most agricultural products, basic computer memory chips, and many other goods are produced in highly competitive markets. The buyers or sellers in these markets are so small that their ability to influence market price is nonexistent. These firms must accept whatever price the market determines, leaving them to decide only how much of the product to produce or buy.

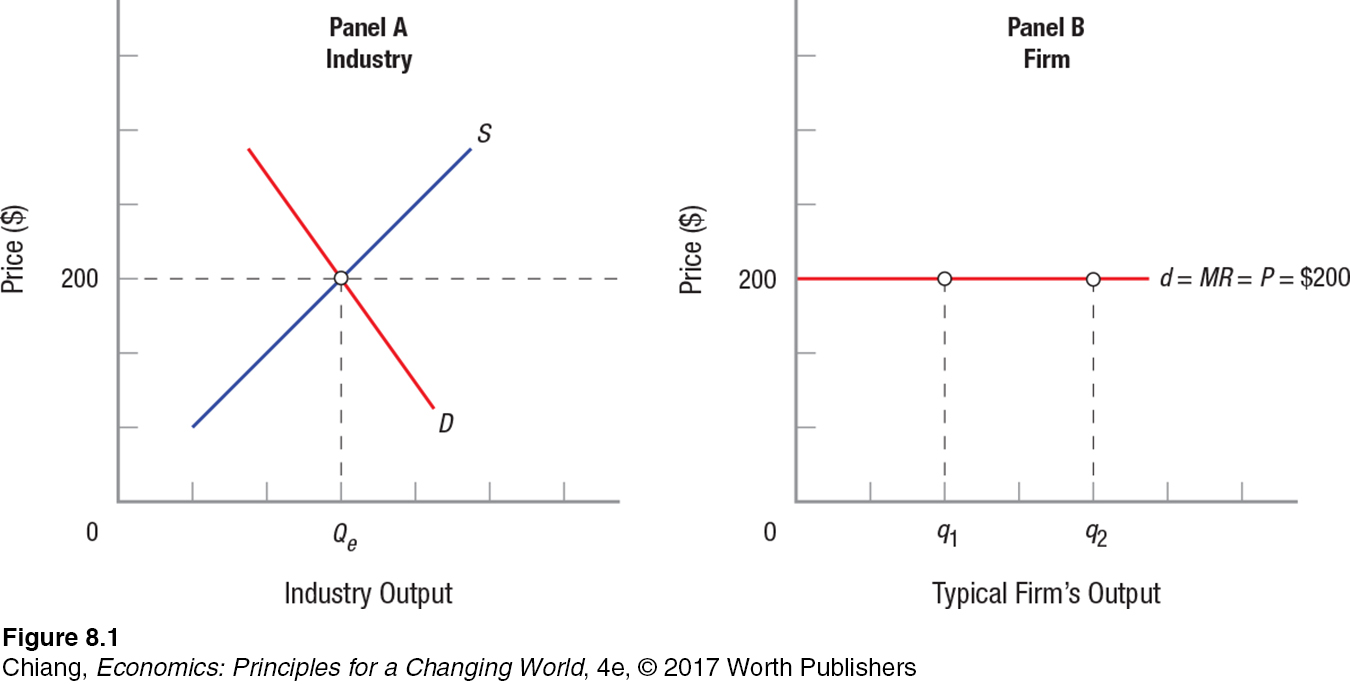

Panel A of Figure 1 portrays the supply and demand for windsurfing sails in a perfectly competitive market; the market is in equilibrium at a price of $200 per sail and industry output Qe. Remember that this product is a standardized sail (similar to 2 × 4 lumber, corn, or crude oil) and that the market contains many buyers and sellers, who collectively set the product price at $200.

Panel B shows the demand for a seller’s products in this market. The firm can sell all it wants at $200 or below. Yet, what firm would set its price below $200 when it can sell everything it produces at $200? Were the firm to set its price above $200, however, it would sell nothing. What consumer, after all, would purchase a standardized sail at a higher price when it can be obtained elsewhere for $200? The individual firm’s demand curve is horizontal at $200. The firm can still determine how much of its product to produce and sell, but this is the only choice it has. The firm cannot set its own price; therefore, it is a price taker.

Recall the profitability equation. Profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals price times quantity sold. In perfectly competitive markets, a firm’s profitability is based on a given market price, quantity sold, and its costs. So how does it determine how much to sell?

The Short Run and the Long Run (A Reminder)

199

Before turning to a more detailed examination of how firms decide how much output to produce in a perfectly competitive market, we need to recall a distinction introduced in the last chapter between the short run and the long run.

In the short run, one factor of production is fixed, usually the firm’s plant size, and firms cannot enter or leave an industry. Thus, in the short run, the number of firms in a market is fixed. Firms may earn economic profits, break even, or suffer losses, but still they cannot exit the industry, nor can new firms enter.

In the long run, all factors are variable, and thus the level of profits induces entry or exit. When losses prevail, some firms will leave the industry and invest their capital elsewhere. When economic profits are positive, new firms will enter the industry. The long run is far more dynamic than the short run.

CHECKPOINT

MARKET STRUCTURE ANALYSIS

Market structure analysis allows economists to categorize industries based on a few characteristics and use this analysis to predict pricing and output behavior.

The intensity of competition is defined by the number of firms in the industry, the nature of the industry’s product, the level of barriers to entry, and how much firms can control prices.

Market structures range from perfect competition (many buyers and sellers), to monopolistic competition (differentiated product), to oligopoly (only a few firms that are interdependent), to monopoly (a one-

firm industry). Perfect competition is defined by four attributes: Many buyers and sellers who are so small that none individually can influence price, firms that produce and sell a homogeneous (standardized) product, buyers and sellers who have all the information necessary to make informed decisions, and barriers to entry and exit that are nonexistent.

Firms in perfectly competitive markets get the product price from national or global markets. In other words, firms are price takers.

In the short run, one factor (usually plant size) is fixed. In the long run, all factors are variable, and firms can enter or leave the industry.

QUESTION: For the following firms, explain where in our market structure approach each firm best fits: Verizon (a wireless communications service provider), NFL (a professional football organization), Grandma’s Southern Kitchen (a small café), Jack’s Lumber (an independent lumber mill).

Answers to the Checkpoint questions can be found at the end of this chapter.

Verizon is one of a few major wireless providers in the U.S. market (others include AT&T, T-