17.1 Chapter Introduction

432

17

CHAPTER OUTLINE

What Is Persuasive Speaking?

Organizing and Supporting Persuasive Speeches

Appealing to Your Audience’s Needs and Emotions

Guidelines for Persuasive Speaking

Sample Persuasive Speech

Persuasive Speaking

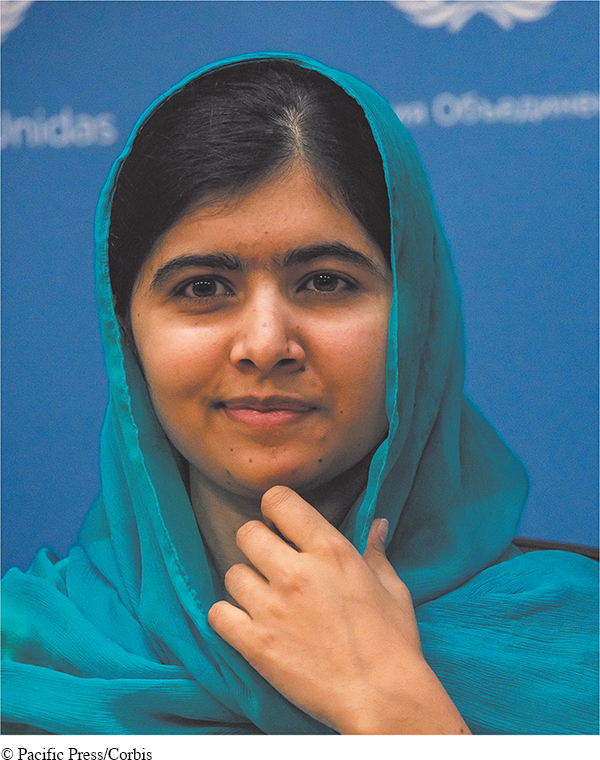

O n her 16th birthday, Malala Yousafzai did something extraordinary. She gave a speech to the United Nations (UN) about the right of every child in developing countries—

1 Chapter opener crafted from Husain (2013).

Inspired by her father’s work as a teacher and educational leader, Malala learned early that formal schooling was a key to prosperity. She was a smart, confident, and exceptional student. But after the Taliban assumed control in the region of Pakistan where she lived, the extremist group banned girls from attending school. Just 11 years old at the time, Malala protested by writing blogs, giving television interviews, and even giving a speech to a Pakistan press club titled “How dare the Taliban take away my basic right to education?” She quickly gained a high profile as an outspoken critic of the Taliban, and in response, the Taliban issued its death warrant on Malala.

Miraculously, Malala survived the gunshot wound to her head and became even more determined to advocate for children’s education. Rather than appeal to her audience’s emotion by seeking pity for what happened, Malala showed strength of character and commitment to her purpose as she spoke to the UN General Assembly:

Dear sisters and brothers, I am not against anyone. Neither am I here to speak in terms of personal revenge against the Taliban or any other terrorists group. I am here to speak up for the right of education of every child. I want education for the sons and the daughters of the Taliban and all the terrorists and extremists. (Yousafzai, 2013, p. 266)

Malala continued her speech by pointing out that terrorist groups fear educated citizens. She described recent attacks on students, teachers, and even medical workers. Using descriptive language, Malala illustrated the difficulty of keeping schools open in some countries:

In many parts of the world, especially Pakistan and Afghanistan, terrorism, war and conflicts stop children from going to schools. We are really tired of these wars. Women and children are suffering in many ways in many parts of the world. In India, innocent and poor children are victims of child labor. Many schools have been destroyed in Nigeria. People in Afghanistan have been affected by extremism. Young girls have to do domestic labor and are forced to get married at an early age. Poverty, ignorance, injustice, racism and the deprivation of basic rights are the main problems faced by both men and women. (Yousafzai, 2013, p. 267)

After explaining the problem, Malala asked the world leaders to ensure access to education for every child around the world. She described pens and books as “powerful weapons” against illiteracy, poverty, and terrorism. She concluded her speech by urging the leaders to see education as the only solution to peace and prosperity.

433

434

Malala continues her work through a nonprofit named for her—

Malala is using persuasive communication on a global stage to change a dire situation. To a much smaller degree, you communicate daily to try to influence others’ attitudes, behaviors, and actions. For instance, on your way to work, you call up a friend and try to persuade her to see the movie you want to see. At your job, you convince a coworker to cover your shift. Persuasive communications like these happen in a wide range of settings. In this chapter, we focus on persuasive speeches—those that reinforce or change listeners’ attitudes and beliefs and possibly even motivate them to take action. These types of presentations may be a requirement of your job or your community involvement.

Persuasive speaking is notably different from coercion. Coercion involves using threats, manipulation, and even violence to force others to do something against their will. Any use of coercion is unethical. When you speak to persuade others, you provide your audience with accurate and honest information, giving them the freedom to choose whether to accept your message or not. In this chapter, you’ll learn:

The different types of persuasive propositions

The importance of credibility in persuasive speaking

How to organize a persuasive speech and support your claims

Strategies for appealing to your audience’s needs and emotions

General guidelines for persuasive speaking