Audience Analysis for Persuasive Speeches

436

After determining your topic and persuasive proposition, the next part of the thinking step includes analyzing the attitudes your audience may have about your message. As Chapter 13 discusses, audience analysis is the process of identifying important characteristics about your listeners, and using this information to prepare your speech. Although you always want to know as much as possible about your audience, paying special attention to any strongly held attitudes, beliefs, and values is especially helpful when preparing a persuasive speech. Will the audience have favorable views toward your topic? Will they strongly oppose your position? Will they be undecided or uncommitted on the issue? Consider the answers to these questions while researching your topic and composing your speech; it will help you create persuasive main points and present your message ethically.

There is one more factor to consider about your listeners when preparing a persuasive speech: How motivated will they be to pay attention?

Understanding the Elaboration Likelihood Model. In Chapter 7 ’s discussion of the listening process, we explain how people go through stages of understanding, interpreting, and evaluating in order to judge the accuracy, interest, and relevance of the messages they hear. But scholars suggest that audience members vary in their motivation and ability to process persuasive messages. Known as the elaboration likelihood model, this theory proposes that listeners who are intensely interested in your topic and can easily understand your presentation will put more effort into thinking about your persuasive message than will listeners who don’t care about or don’t understand your speech topic. Knowing how your audience will process your message will help when you’re composing the presentation. There are two routes listeners can take when processing messages: central and peripheral.

Audience members who are highly motivated to listen and who have the knowledge needed to understand your message will take a central route to processing your speech—

437

Audiences who are less motivated about the topic or who don’t have the time or knowledge needed to understand the information might take a peripheral route to processing your message (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). This means they are not fully engaged with the speech. They may selectively listen for items of personal interest but miss your larger message and therefore not fully understand your thesis. Their attention may wane, or they may get easily distracted. Listeners who take a peripheral route to processing messages can be easily influenced by a speaker’s expertise or emotional appeals, but any changes in attitudes and behaviors are often short lived (Petty, Barden, & Wheeler, 2002). For example, they might give a few dollars to a charity immediately after listening to an emotional appeal but not become regular contributors.

Including the audience in your speech is a sure way to make sure they stay connected and attentive. Using personal pronouns—

Using the Elaboration Likelihood Model. If your audience analysis indicates that most listeners may take a peripheral route to processing your message, there are ways to encourage them to use a central route. Suppose you’re giving a presentation to persuade your classmates to embrace proper nutrition in their daily diet. But most of your classmates don’t see proper nutrition as important and don’t know a lot about the technical details related to nutrition (such as how it affects the body or long-

438

After the speech introduction, you can continue motivating the audience to use central route processing by composing a main point on the positive outcomes of accepting your speech thesis. For example, you could list the advantages of proper nutrition (“By eating healthier, you’ll not only look better but also set a great example for your friends and family”). Additionally, you want to tell them what highly credible experts have said about the issue, so that they understand why good nutrition is something they should care about (“The National Institutes of Health points out that poor nutrition is a contributing factor in obesity, heart disease, and diabetes”). If you present personally relevant, logical, and well-

Finally, researchers Wagner and Petty (2011) suggest that even small changes in language help listeners thoughtfully process persuasive messages. For example, using familiar words rather than technical words makes it easier to listen to a speech. Audience members become distracted and tune out when speakers use language that is hard to understand. Relying on personal pronouns (“You will feel great when you eat well”) instead of impersonal pronouns (“People feel great when they eat well”) encourages listeners to feel personally connected to your message and thus to take a central route in processing your speech (Wagner & Petty, 2011).

Specific Purposes for Persuasive Speeches. When it comes time to write the specific purpose statement for your persuasive speech, keep in mind that most persuasive presentations focus on one of three desired outcomes. First, your speech could reinforce your audience’s existing attitudes and beliefs. Much like the inspiring and rousing speeches given at pep rallies (“This year we win it all!”), this focus is most effective when your listeners already support your position, and your specific purpose is to persuade them to “keep the faith.” In this case, your specific purpose might be “To persuade my audience that we are the best team in the conference.”

Second, if your listeners are uncommitted about your speech topic or if their attitudes and beliefs about the topic differ from yours, your desired outcome might be to change your audience’s attitudes and beliefs. Let’s say you’re talking to an audience that doesn’t care that much about sports, and you want to convince your listeners that your school’s sports program matters. In this case, your specific purpose might be “To convince my audience that a successful sports team is good for student morale.” Since some attitudes and beliefs are at the core of people’s self-

439

A third possible desired outcome is to motivate your audience to take action. This could include taking up a charitable cause, making different choices, or participating in a political action. If your audience is already convinced that successful sports teams improve student morale, your specific purpose could be “To persuade my audience to donate time or supplies to fund-

Credibility in Persuasive Speeches. As a pediatrician and coinventor of the rotavirus vaccine, Dr. Paul Offit spends a lot of time talking with audiences about why it’s important to vaccinate children against certain diseases (Wallace, 2009). During such occasions, he often meets people who disagree with his claim, usually because they believe that childhood vaccines may have unintended consequences—

Even though Offit believes that scientific research has shown no link between vaccinations and autism, he knows that some parents believe there’s a connection. They place a lot of confidence in other sources, such as what they read online or hear other parents say about their own experiences. With so much competing information available, his audience members will have a range of existing knowledge about vaccines and possibly strong attitudes about the topic. Fully aware of the challenge, Offit carefully plans his speeches in order to persuade parents to vaccinate their children (Wallace, 2009).

A critical step for Offit is making sure his listeners find him credible. Credibility is an audience’s perception of a speaker’s trustworthiness and the validity of the information provided in the speech. If your listeners think you’re credible, they are more likely to believe you. If they don’t think you’re credible, you’ll find it difficult to persuade them. The importance of credibility in persuasive speaking can be traced all the way back to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, who pointed out that a speaker’s ethos (credibility) determines whether he or she can influence listeners (Cooper, 1960).

Certainly, a speaker needs more than credibility, or ethos, to be persuasive. According to Aristotle, speakers should also present the audience with good logical reasons (he called this logos) and make appeals to their emotions (pathos). These three elements—

But let’s first look at ethos, or credibility. How exactly do listeners decide whether you’re credible? They consider the three Cs: your character, competence, and charisma.

440

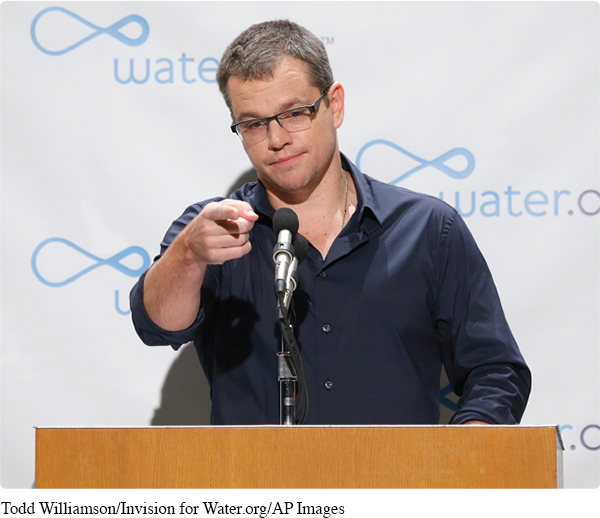

As the cofounder of the organization Water.org, which aims to bring safe water and sanitation to developing countries, actor Matt Damon spends a lot of time influencing audiences to support his cause. Part of his success is due to his ability to connect with audiences on a humane and passionate level, without relying on his celebrity status. How does someone’s general character influence how you listen to him or her?

Character. You demonstrate character by showing your audience that you understand their needs, have their best interests in mind, and genuinely believe in your topic. This communicates that you are trustworthy. Another way to show character is by making it clear to your listeners what they stand to gain by hearing you out. How can you do all this? Determine what you and your audience have in common, and work that into your speech. Building this bridge to your audience conveys the message that you are all in this together.

Competence. When it comes to credibility, competence is the degree of expertise your audience thinks you have regarding your speech topic. Even if you’re not an expert on the subject, you can still convey competence by thoroughly researching it.

One way to demonstrate competence is by using information from only those resources that pass the evaluation requirements discussed in Chapter 13. Your research sources should be highly credible, reliable (objective), and current. In addition, work any personal knowledge or experience you have regarding the topic into your speech. For example, if you want to persuade your listeners to get certified in cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), tell them about your own CPR training experience. Finally, carefully organize and prepare your speech. Even the most knowledgeable, reputable speakers have a hard time looking competent if their material doesn’t follow a logical sequence or if they jump around from point to point.

441

Charisma. Your charisma stems from how much warmth, personality, and dynamism your audience sees in you. Charismatic speakers engage their audience, even when presenting on topics that don’t initially appeal to listeners. Although some people are more naturally outgoing and personable, anyone can work on strengthening their charisma. Even if you’re usually more reserved, you can still practice behaviors that will help you engage with your audience and come across as charismatic. For instance, try varying the volume and pitch of your voice, establishing eye contact with audience members, and moving from behind the lectern and among your listeners if possible. As Chapter 15 describes, using such nonverbal communication skills in your delivery creates immediacy, or a sense of closeness, with your audience. This means they are more likely to view you as warm and approachable and be engaged by your presentation.