Understanding Communication Competence

Communication competence means consistently communicating in ways that are appropriate (your communication follows accepted norms), effective (your communication helps you achieve your goals), and ethical (your communication treats people fairly) (Spitzberg & Cupach, 1984; Wiemann, 1977).

Appropriateness. Appropriateness is the degree to which your communication matches expectations regarding how people “should” communicate. In any setting, norms govern what people should and shouldn’t say, and how they should and shouldn’t act. For example, telling jokes or personal stories about your love life isn’t appropriate during a job interview, but it might be appropriate when you’re hanging out with close friends who know you and your sense of humor. Competent communicators understand when such norms exist and adapt their communication accordingly.

We judge how appropriate our communication is through self-monitoring: the process of observing our own communication and the norms of the situation in order to make appropriate communication choices. Some individuals closely monitor their own communication to ensure they’re acting in accordance with situational expectations (Giles & Street, 1994). Known as high self-monitors, they prefer situations in which clear expectations exist regarding how they’re supposed to communicate, and they possess both the ability and desire to alter their behaviors to fit into any type of social situation (Oyamot, Fuglestad, & Snyder, 2010). In contrast, low self-monitors don’t assess their own communication or the situation (Snyder, 1974). They prefer encounters in which they can “act like themselves” by expressing their values and beliefs, rather than abiding by norms (Oyamot et al., 2010). As a consequence, high self-monitors are often judged as more adaptive and skilled communicators than low self-monitors (Gangestad & Snyder, 2000).

One of the most important choices you make related to appropriateness is when to use mobile devices and when to put them away. Certainly, cell phones and tablets allow us to quickly and efficiently connect with others. However, when you’re interacting with people face-to-face, the priority should be your conversation with them; if you prioritize your device over the person in front of you, you run the risk of being perceived as inappropriate. This is not a casual choice: research documents that simply having cell phones out on a table—but not using them—during face-to-face conversations significantly reduces perceptions of relationship quality, trust, and empathy, compared to having conversations with no phones present (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2012). To avoid such negative judgments, put your mobile devices away at the beginning of the interaction.

Competent communicators also know that overemphasizing appropriateness can backfire. If you always adapt your communication to what others want, you may end up making poor choices. For example, you might give in to peer pressure (Burgoon, 1995). Think of a friend who always does what others want and never argues for his own desires. Is he a competent communicator? No, because he’ll probably seldom achieve goals that are important to him. What about the boss who tells employees that their work is fine even when it isn’t? Is she competent? No, because she’s withholding information her employees need to improve their job performance. Competence means striking a healthy balance between appropriateness and other important considerations, such as achievement of goals and the obligation to communicate honestly.

When Piper Chapman began her one-year sentence at a women’s prison in Orange Is the New Black, her idea of appropriateness quickly changed as she assimilated to her new surroundings. How do you deal with situations in which what you deem as appropriate doesn’t line up with what’s occurring around you?

Jessica Miglio/© Netflix/courtesy Everett Collection

Effectiveness. Effectiveness is the ability to use communication to accomplish the three types of goals discussed earlier (self-presentation, instrumental, and relationship). Sometimes you have to make trade-offs—prioritizing certain goals over others, even if you want to pursue all of them. For instance, to collaborate effectively with groups, you have to know when to stay on task and when to socialize. Say that you and several other students form an intramural softball team to compete in a campus league. At the first team meeting, you may want to come across as athletic, funny, and likable (self-presentation goal) and begin building friendships with others on the team (relationship goal). But if you don’t focus your communication during the meeting on creating a practice schedule (instrumental goal), the team won’t be ready to play its first game. Chapter 12 discusses how you can be an effective leader and communicator in such situations.

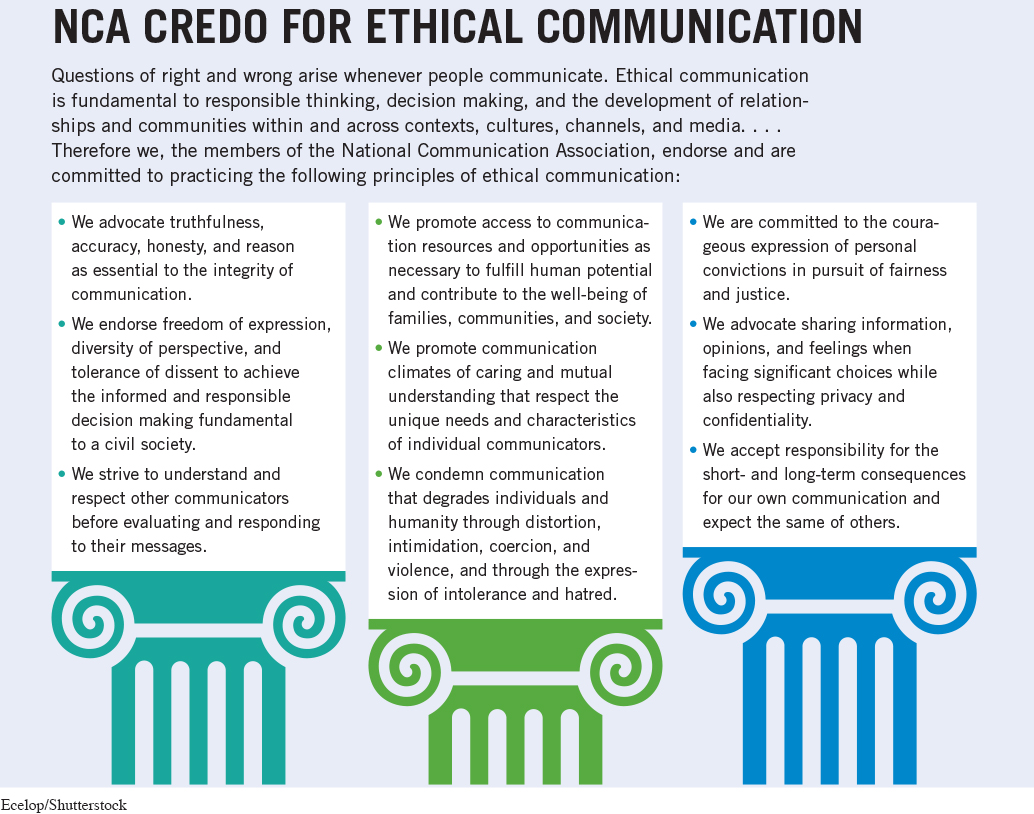

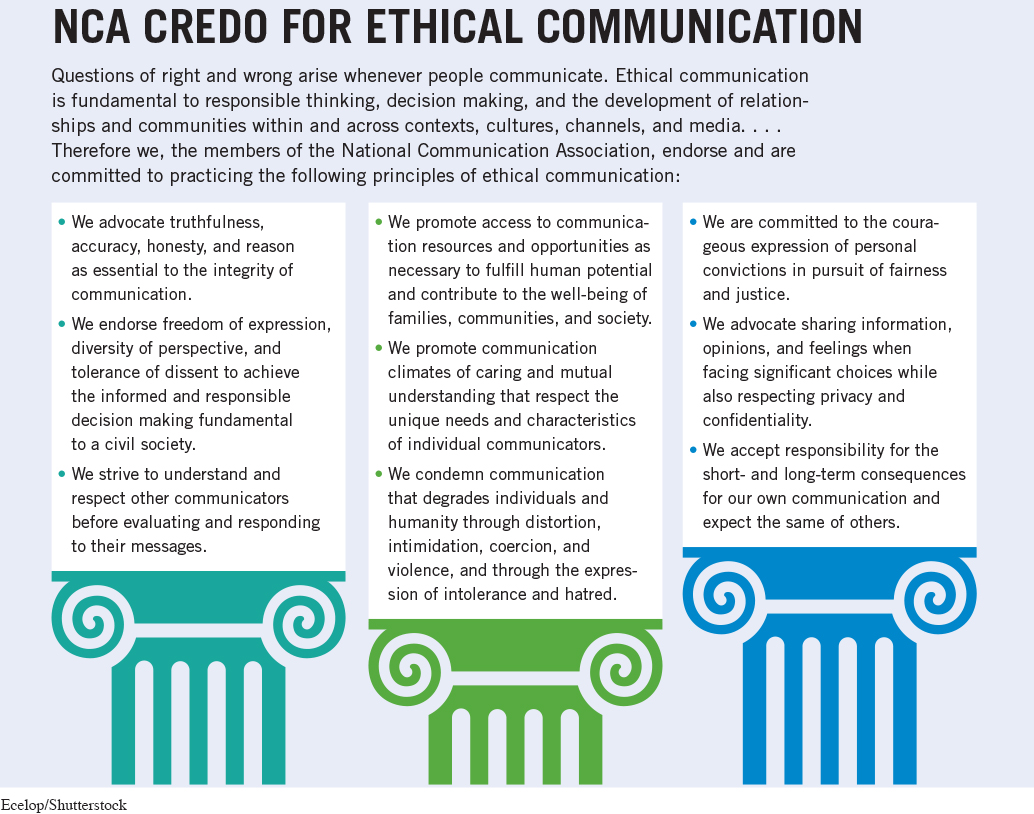

Ethics. Ethics is the set of moral principles that guide your behavior toward others (Spitzberg & Cupach, 2002). At a minimum, you are ethically obligated to avoid intentionally hurting others through your communication. By this standard, communication that’s intended to erode a person’s self-esteem, that expresses intolerance or hatred, that intimidates or threatens others’ physical well-being, or that expresses violence is unethical and therefore incompetent (Parks, 1994).

However, to be an ethical communicator, you must go beyond simply not doing harm. During every encounter—whether it’s interpersonal, a small group, or a public presentation—you need to treat others with respect and communicate with them honestly, kindly, and positively (Englehardt, 2001). As you’ll see in Chapter 3, mediated communication presents unique challenges for ethical communication. To help you make ethical choices in all situations, consider the guidelines in the National Communication Association’s Credo for Ethical Communication (1999) in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.5: FIGURE 1.4 NCA CREDO FOR ETHICAL COMMUNICATION

Ecelop/Shutterstock

In communication situations that are simple, comfortable, and pleasant, it’s easy to behave appropriately, effectively, and ethically. True competence, however, develops when you consistently communicate competently across all situations that you face—even ones that are complex, uncertain, and unpleasant. A critical goal of this book is to equip you with the knowledge and skills you need to handle those more challenging communication situations. For example, the How to Communicate: Competent Conversations feature on pages 24–25 asks you to adapt your understanding of communication competence to an unpleasant encounter.