Creating Your Online Face

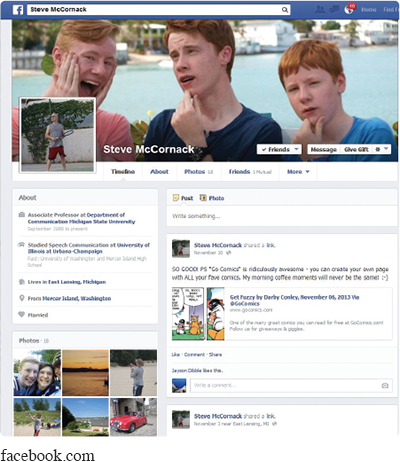

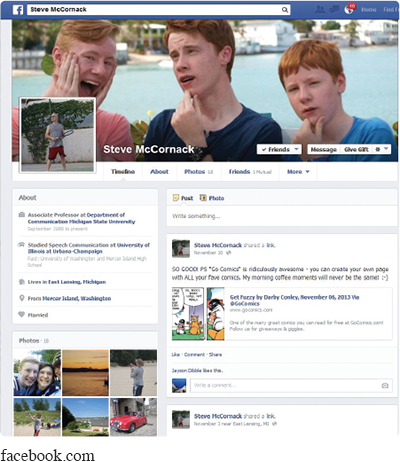

Scholars studying mediated communication suggest that three elements largely determine your online face: your posted content, your e-mail and screen names, and your friends and professional connections.

Posted Content. Everything you post online communicates information about who you are and how you wish to be seen. A status update like, “Monster trucks one night, demolition derby the next—Gotta love the county fair!” or a tweet that reads, “$1 oysters until 7 pm at Harpers—come hang with the gang!” communicates powerful messages about your tastes, interests, and social identity (you’re a “country” person; you’re a “foodie”). The same goes for posting, sharing, and tagging photographs and videos.

Online faces are far from objective, however. People post content to amplify positive personality characteristics, such as warmth, friendliness, and extraversion (Vazire & Gosling, 2004). For instance, photos on social networking sites typically show groups of friends, giving the impression that the person in the profile is likable, fun, and popular (Ellison, Steinfield, & Lampe, 2007). These positive and highly selective depictions of self generally work. When viewing someone’s profile, you tend to believe what you see and form the same impressions about the person that he or she intended (Gosling, Gaddis, & Vazire, 2007).

Of course, it’s not just what you post about yourself that determines your online face—it’s also the content that others post about you. Research shows that when friends, family members, coworkers, or romantic partners post information about you, their content shapes others’ perceptions of you even more powerfully than your own postings do—especially when their postings contradict your self-description (Walther, Van Der Heide, Kim, Westerman, & Tong, 2008).

Why do others’ posts have so much power? When evaluating someone’s online description, you consider the warranting value of the information presented—that is, the degree to which the information is supported by other people and outside evidence (Walther, Van Der Heide, Hamel, & Schulman, 2009). Information that was obviously crafted by the person, that isn’t supported by others online, or that can’t be verified offline has low warranting value. For example, people may not trust an online profile in which you describe yourself as fun and outgoing when there are no posted comments from others to support your description. But your profile information has high warranting value if the social media feed has photos of you in social settings and relevant posted comments from others (“You were SO MUCH fun to hang with last night!”) (Walther et al., 2009).

The research on warranting value suggests that you need to manage online content posted by others that contradicts the self you want to present—even if you think such content is cute or funny. If you want to track what others are posting about you, set up a Google Alert or regularly search for your name and other identifying keywords. If anyone posts information about you that doesn’t match how you want to be seen, politely ask that person to delete it. For more on managing your online face, see How to Communicate: Removing an Embarrassing Post on pages 70–71.

Your online self-presentation is also influenced by the people you follow, the tags you use, and the posts you like. One advantage of social media is that these markers make it easy for you to find and follow people with similar interests.

facebook.com

E-mail and Screen Names. The name you use for your e-mail address, online profiles, or Web site tells others how you want to be perceived (Baym, 2010). Although it is tempting to underestimate their impact, these names create powerful impressions. On dating Web sites, for example, screen names that are playful or represent physical traits (“Fun2bwith,” “Blueeyes”) are rated by viewers as attractive (Whitty & Buchanan, 2010). Neutral screen names (“0257”) or names suggesting wealth (“Silverspoon”) convey a sense that the individual is boring or arrogant (Whitty & Buchanan, 2010).

However, what works for one site may not be a good idea in other contexts. You wouldn’t want to use your dating profile name (“Fun2bwith”) for an e-mail address on a job application. For example, Joe maintains a professional identity through his academic e-mail address (joseph.ortiz@scottsdalecc.edu), which states his full name and the school where he teaches. But in fantasy baseball forums, his screen name—joeStros13—reflects a more casual identity. Steve does the same thing within online audio circles he belongs to that celebrate turntables, vinyl records, and tubed amplifiers: there, he is “The Analog Kid” (in honor of one of his favorite Rush songs). Carefully choose screen names based on the audience to which you are trying to appeal.

Friends and Professional Connections. Lists of your friends on Facebook, your professional connections on LinkedIn, and your followers on Twitter can also give impressions about your social status, political ideology, and other interests (Donath & boyd, 2004). For example, if you’re linked to people who post frequently about animal rights, someone looking at your profile might assume that this cause is important to you, too. Even the number of friends listed on your profile creates impressions. In one study, individuals with about 300 friends on Facebook were viewed as more likable than those with 100 friends or a lot more than 300 friends (Tong, Van Der Heide, Langwell, & Walther, 2008). Why? Having “too few” Facebook friends made people seem unpopular. Having “too many” made them appear to spend too much time online or seem indiscriminate in their choice of friends.