Chapter 9 America in the Modern World: 1913—1945

1913–1945

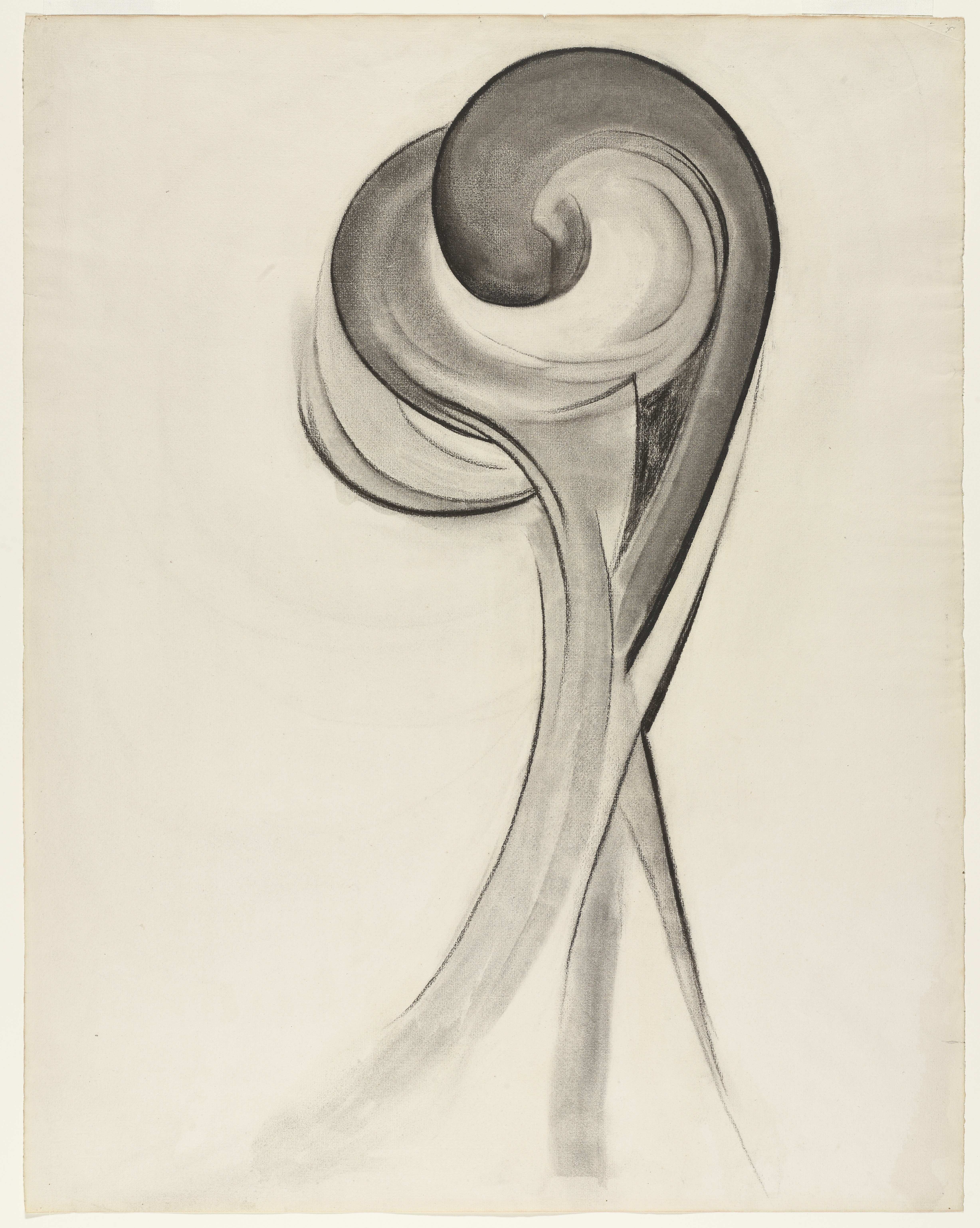

The decades surrounding the turn of the twentieth century were a time of unprecedented change. The world was still wrestling with the groundbreaking ideas of the late nineteenth century: Sigmund Freud’s notion of the unconscious mind (the id), Karl Marx’s socialism, Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, and Friedrich Nietzsche’s nihilist mantra “God is dead” that announced a growing secularization in society. Meanwhile, the United States, and much of the Western world, was experiencing rapid industrialization, a boom in urban populations, and a flurry of scientific and technological breakthroughs that would lay the foundation for modern life. Inasmuch as humanity had ever been confident that it understood itself, life, or the world we live in, these destabilizing forces shattered that confidence. Traditional art forms suddenly seemed incapable of representing the mystery, complexity, and uncertainty of modern life. Not to mention the fact that Kodak’s invention of the simple, affordable “Brownie” camera in 1900 meant that making representative visual art no longer required years of training, but just a simple click of the shutter. The response to these changes was a movement called modernism—marked by abstract art, symbolic poetry, and stream-of-consciousness prose—that tried to represent the subjective experience of modern life rather than the objective reality of it. It was driven by innovation in form and content. As poet Ezra Pound declared, “Make it new!” The unofficial starting point of modernism in America was the 1913 Armory Show, officially titled the International Exhibition of Modern Art, which introduced American audiences to the works of European modern artists such as Henri Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, and Pablo Picasso. In this chapter, you will study works by Ezra Pound, Marsden Hartley, Wallace Stevens, T. S. Eliot, William Carlos Williams, Charles Demuth, and other modernist pioneers who made American art and literature new.

Amid this cultural tumult came what President Woodrow Wilson called “the war to end all wars.” Urging Congress to declare war on Germany in 1917, Wilson called for America to spread liberty across the world, which must be “made safe for democracy.” World War I was one of the bloodiest wars in recorded history, with a deadly combination of primitive trench-warfare tactics and modern weaponry taking nearly 9 million lives. It was also one of the most politically bewildering, beginning as a struggle between the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Serbia before a tangled web of alliances dragged Russia, Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, the Ottoman Empire, Japan, Bulgaria, and ultimately the United States into the conflict. Although World War I began in 1914, the United States did not get involved until April 1917, spurred to action by the 1915 German sinking of the British ocean liner Lusitania, which killed 128 Americans, and the sinking of seven American merchant ships in January 1917. The United States remained actively engaged in the conflict until its conclusion in November 1918, mobilizing more than 4 million troops and suffering approximately 110,000 casualties—43,000 of which stemmed from an influenza epidemic. World War I ushered in a new era of American military might and American industrialization; through its presence in the war, America made good on Wilson’s promise, as it spread its principles of reform, freedom, and democracy.

The United States emerged from World War I into a period of relative peace and prosperity. Cities were burgeoning, reforms were taking hold, and success in the war gave rise to a feeling of American security and self-confidence. The so-called Roaring Twenties epitomized this sentiment. The 1920s saw a dramatic increase in Americans’ cars, telephones, and electricity; we turned our attention to celebrity culture through the movies and sports through the construction of giant stadiums. Industries boomed as American consumers demanded new and better innovations. Women gained the right to vote in 1920, giving them a voice in American political life for the first time. “Flapper” culture encouraged women to shake off the constraints of nineteenth-century fashion; women stopped wearing corsets, showed off their arms and legs, cut their hair short, and wore makeup.

During the 1920s, American literature, art, and music changed dramatically. New York City’s uptown Harlem neighborhood was the center of the New Negro Movement, later called the Harlem Renaissance, as art, literature, and music by African Americans found new expression. Harlem was a destination for many migrant African Americans seeking work and economic opportunity; it was also home to a new African American middle class. The works by Langston Hughes, Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, and Richard Wright in this chapter will ask you to consider issues of equality, racial pride, stereotyping, integration, and identity. In this chapter’s Conversation on the influence of jazz, we will explore the cultural impact of this music and how other arts were inspired by its new, experimental, and genuinely American form of expression.

The Roaring Twenties came to a screeching halt when the stock market crashed on October 29, 1929, the day known as “Black Tuesday.” Wall Street collapsed, and the United States slipped into a severe economic downturn that led to the Great Depression. The Great Depression dragged on throughout the 1930s, with unemployment rates reaching nearly 25 percent. To make matters worse, a catastrophic drought and erosion from poor farming practices caused a dust bowl in the American Midwest, where agricultural production halted and farmers were displaced from their land.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt was inaugurated in 1933, and his series of progressive reforms and programs, known as the New Deal, slowly began to improve the lives of suffering Americans. Roosevelt’s second inaugural address and his First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s speech “What Libraries Mean to the Nation” will help you understand the circumstances of American life during the Great Depression, as well as the enduring role of literature throughout difficult periods of our history. Works by John Steinbeck and William Faulkner also explore rural American life during the 1930s.

By the end of the 1930s, another war was raging throughout Europe. As in the previous conflict, the United States at first chose not to engage in the war. However, on December 7, 1941, Japan attacked the American naval fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and thrust America into the Second World War, fighting against Japan, Germany, and Italy. World War II ended up being the deadliest, costliest, and most sprawling war in recorded history. Over 16 million Americans fought in the military—290,000 were killed and 670,000 were wounded. Randall Jarrell’s famous poem “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner” takes us into the world of one soldier.

Everyday life on the home front was dramatically altered during World War II. Food, clothing, and gas were rationed. Women joined the war effort by taking jobs as electricians, riveters, and welders in factories producing goods for the war. The lives of Japanese Americans were shattered when they were forced into internment camps on the off chance they might be spies, a wartime policy now universally regarded as one of the most egregious stains on our nation’s history and reputation. A cluster of texts in this chapter asks you to investigate the internment of Japanese Americans and to consider if it is possible to right the wrongs of the past through reparations.

The Second World War ended with a bang. And that bang would change the world forever. Atomic bombs dropped by the United States on Hiroshima and Nagasaki not only ended the war in the Pacific but also propelled the nation into the atomic age. In this chapter, you will read the speech President Harry S Truman gave announcing this destructive event and the arrival of America as a global superpower.

As it turned out, despite the great loss of life and widespread destruction, World War II was exactly the economic stimulus that America needed to end the Great Depression. The country emerged from the war as a global military and economic superpower primed for a new era of prosperity.