10.4 Psychophysiological Disorders: Psychological Factors Affecting Other Medical Conditions

About 85 years ago, clinicians identified a group of physical illnesses that seemed to be caused or worsened by an interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors (Dunbar, 1948; Bott, 1928). Early editions of the DSM labeled these illnesses psychophysiological, or psychosomatic, disorders, but DSM-

psychophysiological disorders Disorders in which biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors interact to cause or worsen a physical illness. Also known as psychological factors affecting other medical conditions.

psychophysiological disorders Disorders in which biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors interact to cause or worsen a physical illness. Also known as psychological factors affecting other medical conditions.

|

Psychological Factors Affecting Other Medical Conditions |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

The presence of a medical condition. |

|

2. |

Psychological factors negatively affect the medical condition by:

|

|

(Information from: APA, 2013) |

|

It is important to recognize that significant medical symptoms and conditions are involved in psychophysiological disorders and that the disorders often result in serious physical damage (APA, 2013). They are different from the factitious, conversion, and illness anxiety disorders that are accounted for primarily by psychological factors.

331

Traditional Psychophysiological Disorders

Before the 1970s, clinicians believed that only a limited number of illnesses were psychophysiological. The best known and most common of these disorders were ulcers, asthma, insomnia, chronic headaches, high blood pressure, and coronary heart disease. Recent research, however, has shown that many other physical illnesses—

Ulcers are lesions (holes) that form in the wall of the stomach or of the duodenum, resulting in burning sensations or pain in the stomach, occasional vomiting, and stomach bleeding. More than 25 million people in the United States have ulcers at some point during their lives, and ulcers cause an estimated 6,500 deaths each year (Stratemeier & Vignogna, 2014; Simon, 2013). Ulcers often are caused by an interaction of stress factors, such as environmental pressure or intense feelings of anger or anxiety (see Figure 10-2), and physiological factors, such as the bacteria H. pylori (Marks, 2014; Fink, 2011; Carr, 2001).

ulcer A lesion that forms in the wall of the stomach or of the duodenum.

ulcer A lesion that forms in the wall of the stomach or of the duodenum.

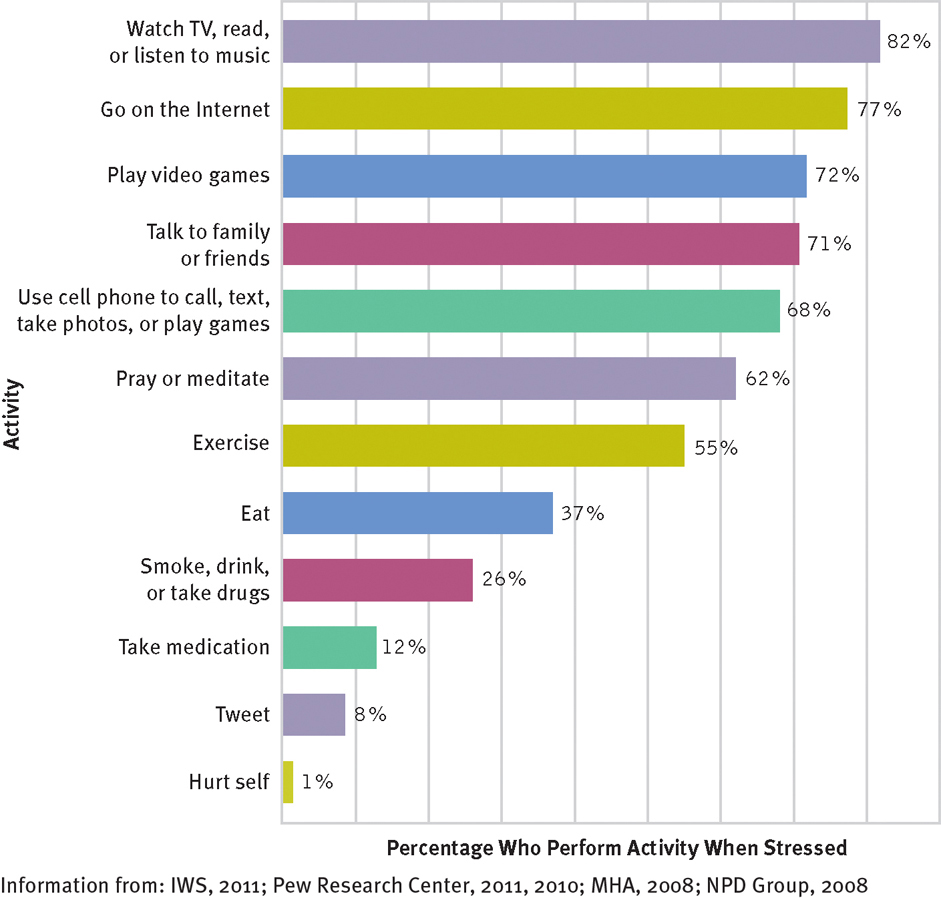

What do people do to relieve stress?

According to surveys, most of us go on the Internet, watch television, read, or listen to music. Tweeting is on the rise.

Asthma causes the body’s airways (the trachea and bronchi) to narrow periodically, making it hard for air to pass to and from the lungs. The resulting symptoms are shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, and a terrifying choking sensation. Some 235 million people in the world—

asthma A medical problem marked by narrowing of the trachea and bronchi, which results in shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, and a choking sensation.

asthma A medical problem marked by narrowing of the trachea and bronchi, which results in shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, and a choking sensation.

332

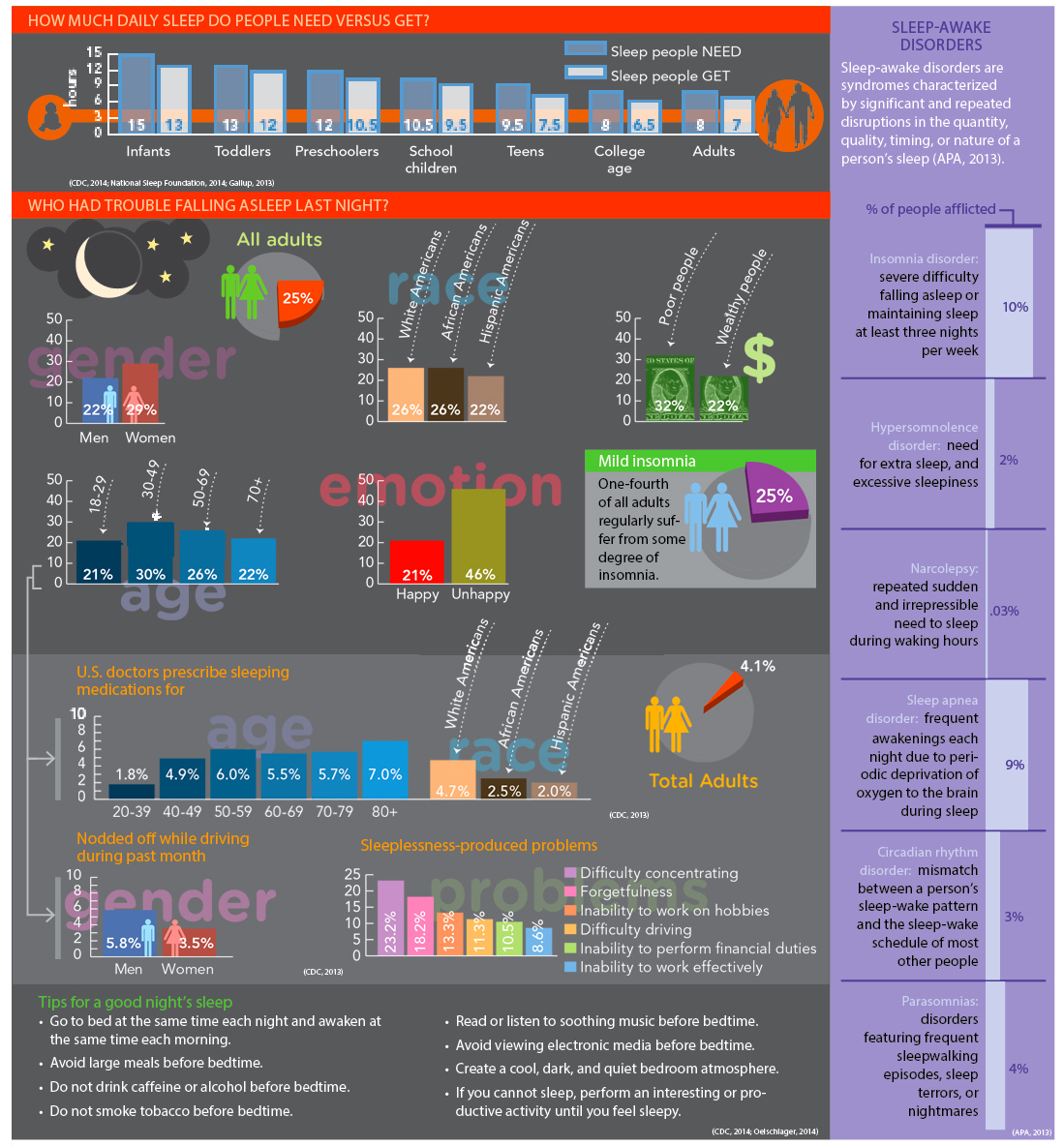

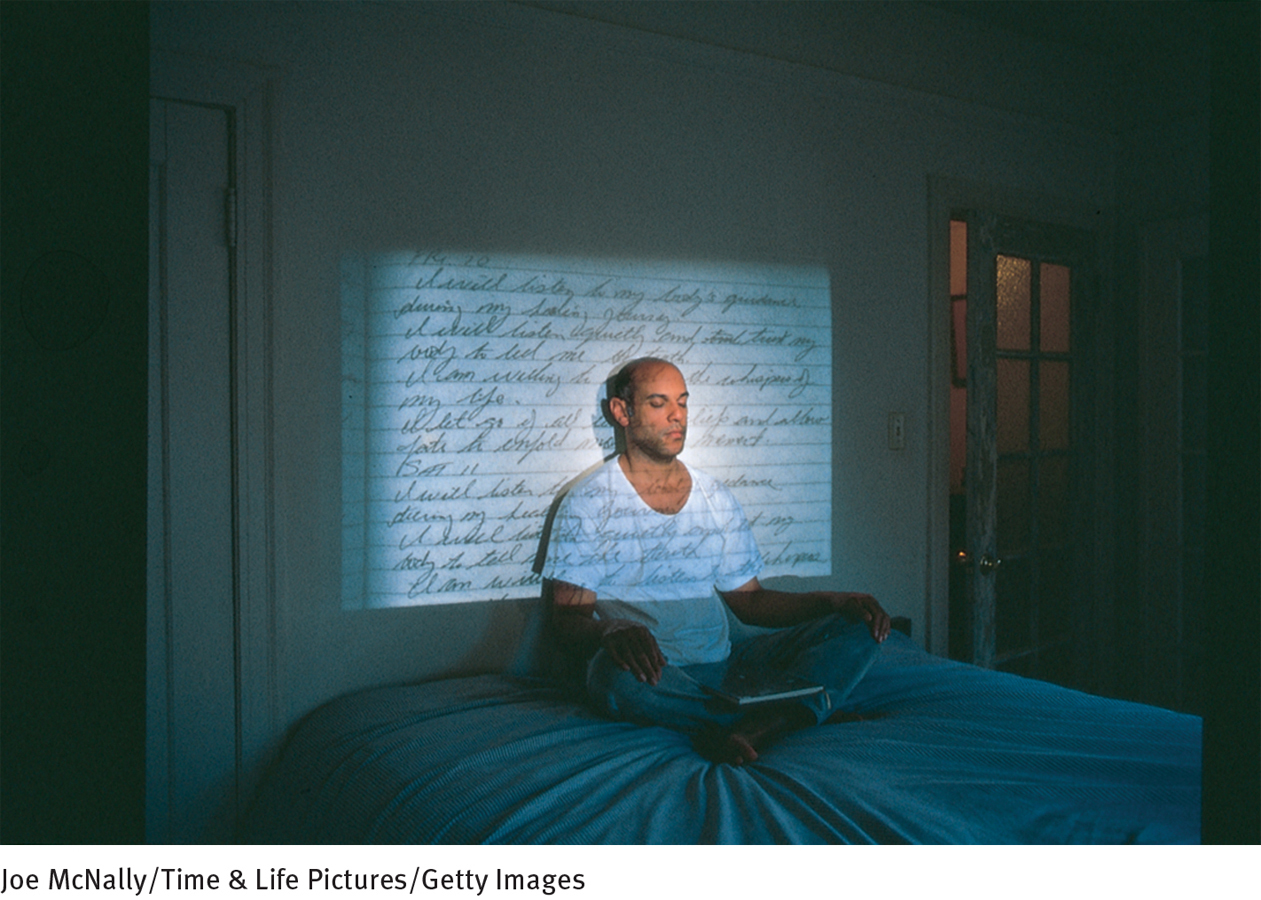

Insomnia, difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep, plagues more than one-

insomnia Difficulty falling or staying asleep.

insomnia Difficulty falling or staying asleep.

Chronic headaches are frequent intense aches of the head or neck that are not caused by another physical disorder. There are two major types. Muscle contraction, or tension, headaches are marked by pain at the back or front of the head or the back of the neck. These occur when the muscles surrounding the skull tighten, narrowing the blood vessels. Approximately 45 million Americans suffer from such headaches (CDC, 2010).

muscle contraction headache A headache caused by a narrowing of muscles surrounding the skull. Also known as tension headache.

muscle contraction headache A headache caused by a narrowing of muscles surrounding the skull. Also known as tension headache.

Migraine headaches are extremely severe, often nearly paralyzing headaches that are located on one side of the head and are sometimes accompanied by dizziness, nausea, or vomiting. Migraine headaches are thought by some medical theorists to develop in two phases: (1) blood vessels in the brain narrow, so that the flow of blood to parts of the brain is reduced, and (2) the same blood vessels later expand, so that blood flows through them rapidly, stimulating many neuron endings and causing pain. Twenty-

migraine headache A very severe headache that occurs on one side of the head, often preceded by a warning sensation and sometimes accompanied by dizziness, nausea, or vomiting.

migraine headache A very severe headache that occurs on one side of the head, often preceded by a warning sensation and sometimes accompanied by dizziness, nausea, or vomiting.

333

Research suggests that chronic headaches are caused by an interaction of stress factors, such as environmental pressures or general feelings of helplessness, anger, anxiety, or depression, and physiological factors, such as abnormal activity of the neurotransmitter serotonin, vascular problems, or muscle weakness (Young & Skorga, 2011; Engel, 2009).

Hypertension is a state of chronic high blood pressure. That is, the blood pumped through the body’s arteries by the heart produces too much pressure against the artery walls. Hypertension has few outward signs, but it interferes with the proper functioning of the entire cardiovascular system, greatly increasing the likelihood of stroke, heart disease, and kidney problems. Around 9.4 million deaths around the world are caused by hypertension (WHO, 2013). It is estimated that 75 million people in the United States have hypertension, thousands die directly from it annually, and millions more perish because of illnesses caused by it (CDC, 2014, 2011; Ford & LaVan, 2011). Around 10 percent of all cases are caused by physiological abnormalities alone; the rest result from a combination of psychological and physiological factors and are called essential hypertension. Some of the leading psychosocial causes of essential hypertension are constant stress, environmental danger, and general feelings of anger or depression. Physiological factors include obesity, smoking, poor kidney function, and an unusually high proportion of the gluey protein collagen in a person’s blood vessels (Brooks et al., 2011; Landsbergis et al., 2011).

hypertension Chronic high blood pressure.

hypertension Chronic high blood pressure.

What jobs in our society might be particularly stressful and traumatizing? Might certain lifestyles be more stressful than others?

Coronary heart disease is caused by a blocking of the coronary arteries, the blood vessels that surround the heart and are responsible for carrying oxygen to the heart muscle. The term actually refers to several problems, including blockage of the coronary arteries and myocardial infarction (a “heart attack”). Coronary heart disease is the leading cause of death globally, resulting in 7.3 million deaths each year. (WHO, 2013). In the United States, nearly 18 million people have some form of coronary heart disease. It is the leading cause of death for both men and women in the nation, accounting for 600,000 deaths each year, around 40 percent of all deaths (CDC, 2014; AHA, 2011). The majority of all cases of coronary heart disease are related to an interaction of psychosocial factors, such as job stress or high levels of anger or depression, and physiological factors, such as high cholesterol, obesity, hypertension, smoking, or lack of exercise (Bekkouche et al., 2011; Kendall-

coronary heart disease Illness of the heart caused by a blockage in the coronary arteries.

coronary heart disease Illness of the heart caused by a blockage in the coronary arteries.

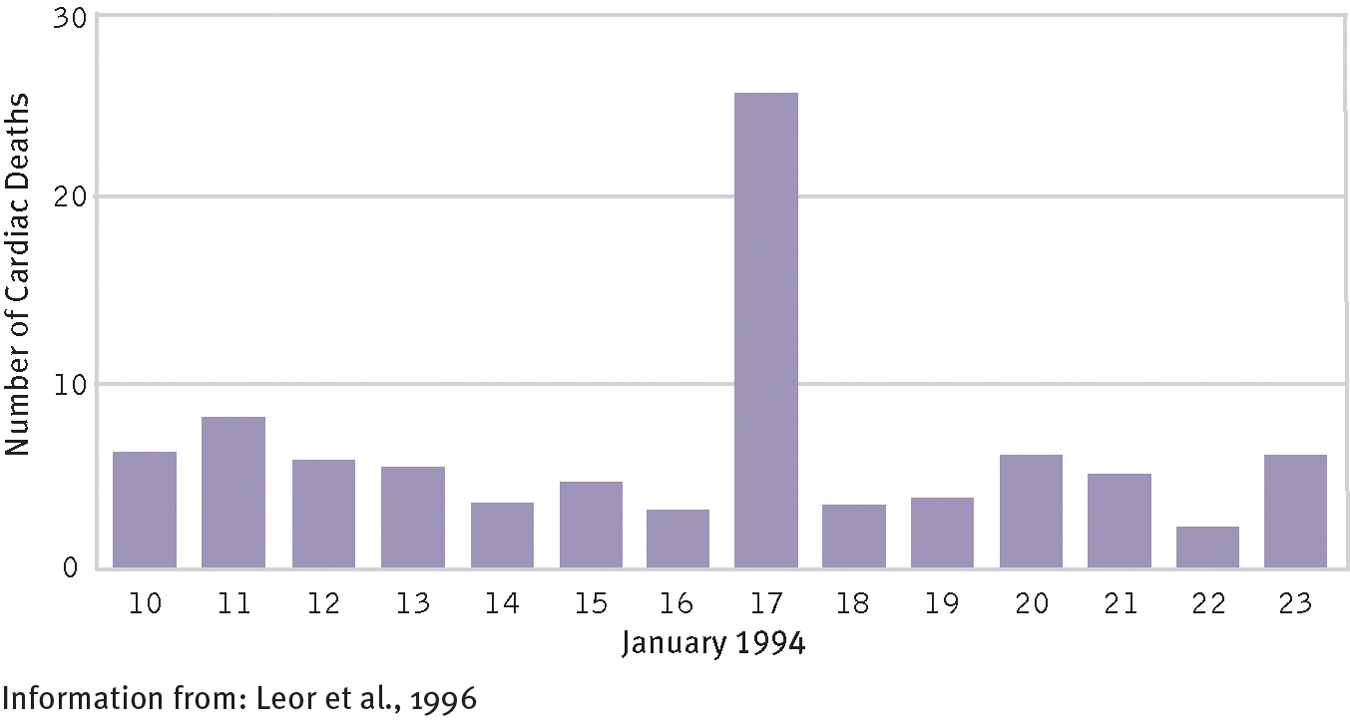

Coronary heart disease and stress

On January 17, 1994, Los Angeles was struck by an enormous earthquake. Twenty-

334

InfoCentral

SLEEP AND SLEEP DISORDERS

Sleep is a naturally recurring state that features altered consciousness, suspension of voluntary bodily functions, muscle relaxation, and reduced perception of environmental stimuli. Researchers have acquired much data about the stages, cycles, brain waves, and mechanics of sleep, but they do not fully understand its precise purpose. We do know, however, that humans and other animals need sleep to survive and function properly.

335

What Factors Contribute to Psychophysiological Disorders?Over the years, clinicians have identified a number of variables that may generally contribute to the development of psychophysiological disorders. You may notice that several of these variables are the same as those that contribute to the onset of acute and posttraumatic stress disorders (see Chapter 6). The variables can be grouped as biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors, respectively.

BIOLOGICAL FACTORSYou saw in Chapter 6 that one way the brain activates body organs is through the operation of the autonomic nervous system (ANS), the network of nerve fibers that connect the central nervous system to the body’s organs. Defects in this system are believed to contribute to the development of psychophysiological disorders (Lundberg, 2011; Hugdahl, 1995). If one’s ANS is stimulated too easily, for example, it may overreact to situations that most people find only mildly stressful, eventually damaging certain organs and causing a psychophysiological disorder. Other more specific biological problems may also contribute to psycho-

In a related vein, people may display favored biological reactions that raise their chances of developing psychophysiological disorders. Some individuals perspire in response to stress, others develop stomachaches, and still others have a rise in blood pressure (Lundberg, 2011). Research has indicated, for example, that some people are particularly likely to have temporary rises in blood pressure when stressed (Su et al., 2014; Gianaros & O’Connor, 2011). It may be that they are prone to develop hypertension.

PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORSAccording to many theorists, certain needs, attitudes, emotions, or coping styles may cause people to overreact repeatedly to stressors, and so increase their chances of developing psychophysiological disorders (Williams et al., 2011). Researchers have found, for example, that men with a repressive coping style (a reluctance to express discomfort, anger, or hostility) tend to have a particularly sharp rise in blood pressure and heart rate when they are stressed (Trapp et al., 2014; Myers, 2010).

Another personality style that may contribute to psychophysiological disorders is the Type A personality style, an idea introduced a half-

Type A personality style A personality pattern characterized by hostility, cynicism, drivenness, impatience, competitiveness, and ambition.

Type A personality style A personality pattern characterized by hostility, cynicism, drivenness, impatience, competitiveness, and ambition.

Type B personality style A personality pattern in which a person is more relaxed, less aggressive, and less concerned about time.

Type B personality style A personality pattern in which a person is more relaxed, less aggressive, and less concerned about time.

The link between the Type A personality style and coronary heart disease has been supported by many studies. In one well-

Recent studies indicate that the link between the Type A personality style and heart disease may not be as strong as the earlier studies suggested. These studies do suggest, however, that several of the characteristics that supposedly make up the Type A style, particularly hostility and time urgency, may indeed be strongly related to heart disease (Williams et al., 2013; Elovainio et al., 2011; Myrtek, 2007).

336

SOCIOCULTURAL FACTORS: THE MULTICULTURAL PERSPECTIVEAdverse social conditions may set the stage for psychophysiological disorders (Su et al., 2014). Such conditions produce ongoing stressors that trigger and interact with the biological and personality factors just discussed. One of society’s most negative social conditions, for example, is poverty. In study after study, it has been found that relatively wealthy people have fewer psychophysiological disorders, better health in general, and better health outcomes than poor people (Singh & Siahpush, 2014; Chandola & Marmot, 2011). One obvious reason for this relationship is that poorer people typically experience higher rates of crime, unemployment, overcrowding, and other negative stressors than wealthier people. In addition, they typically receive inferior medical care.

The relationship between race and psychophysiological and other health problems is complicated. On the one hand, as one might expect from the economic trends just discussed, African Americans have more such problems than do white Americans. African Americans have, for example, higher rates of high blood pressure, diabetes, and asthma (Wang et al., 2014; CDCP, 2011). They are also more likely than white Americans to die of heart disease and stroke. Certainly, economic factors may help explain this racial difference. Many African Americans live in poverty; those who do often must contend with the high rates of crime and unemployment that often result in poor health conditions (Greer et al., 2014).

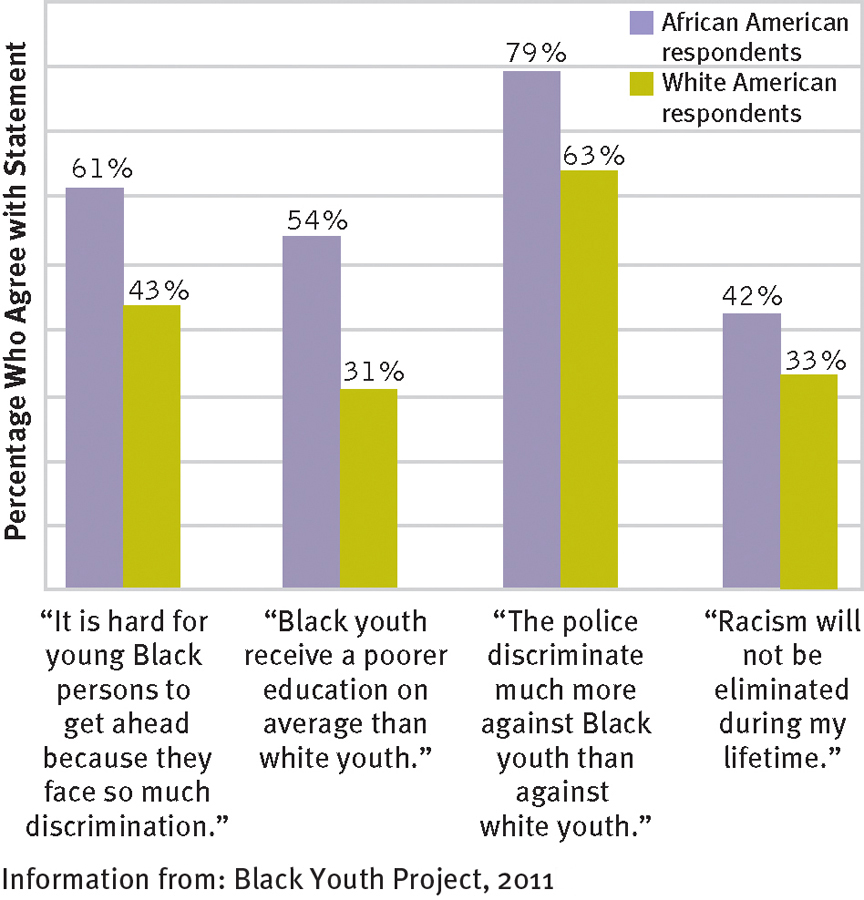

Research further suggests that the high rate of psychophysiological and other medical disorders among African Americans probably extends beyond economic factors. Consider, for example, the finding that 42 percent of African Americans have high blood pressure, compared with 29 percent of white Americans (CDCP, 2011). Although this difference may be explained in part by the dangerous environments in which so many African Americans live and the unsatisfying jobs at which so many must work (Gilbert et al., 2011; Jackson et al., 2010), other factors may also be operating. A physiological predisposition among African Americans may, for example, increase their risk of developing high blood pressure. Or it may be that repeated experiences of racial discrimination constitute special stressors that help raise the blood pressure of African Americans (Dolezsar et al., 2014) (see Figure 10-4). In fact, some recent investigations have found that the more discrimination people experience over a 1-

How much discrimination do racial minority teenagers face?

It depends on who’s being asked the question. In a recent survey of 1,590 teenagers and young adults, African American respondents were more likely than white American respondents to recognize that African American teens experience various forms of discrimination.

Looking at the health picture of African Americans, one might expect to find a similar trend among Hispanic Americans. After all, a high percentage of Hispanic Americans also live in poverty, are exposed to discrimination, are affected by high rates of crime and unemployment, and receive inferior medical care (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010; Travis & Meltzer, 2008). However, despite such disadvantages, the health of Hispanic Americans is, on average, at least as good and often better than that of both white Americans and African Americans (CDCP, 2011; Mendes, 2010). As you can see in Table 10-7, for example, Hispanic Americans have lower rates of high blood pressure, high cholesterol, asthma, and cancer than white Americans or African Americans do.

|

|

High Blood Pressure |

High Cholesterol |

Diabetes |

Asthma |

Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

African Americans |

42% |

24% |

16% |

13% |

5% |

|

White Americans |

29% |

30% |

11% |

11% |

8% |

|

Hispanic Americans |

21% |

20% |

11% |

9% |

3% |

|

(Information from: CDCP, 2011; Mendes, 2010) |

|||||

The relatively positive health picture for Hispanic Americans in the face of clear economic disadvantage has been referred to in the clinical field as the “Hispanic Health Paradox.” Generally, researchers are puzzled by this pattern, but a few explanations have been offered. It may be, for example, that the strong emphasis on social relationships, family support, and religiousness that often characterize Hispanic American cultures increase health resilience among their members (Dubowitz et al., 2010; Gallo et al., 2009). Or Hispanic Americans may have a physiological predisposition that improves their likelihood of having better health outcomes.

337

New Psychophysiological Disorders

Clearly, biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors combine to produce psychophysiological disorders. In fact, the interaction of such factors is now considered the rule of bodily functioning, not the exception. As the years have passed, more and more illnesses have been added to the list of traditional psychophysiological disorders and researchers have found many links between psychosocial stress and a wide range of physical illnesses. Let’s look at how these links were established and then at psychoneuroimmunology, the area of study that ties stress and illness to the body’s immune system.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Room with a View

According to one hospital’s records of individuals who underwent gallbladder surgery, those in rooms with a good view from their window had shorter hospitalizations and needed fewer pain medications than those in rooms without a good view (Ulrich, 1984).

Are Physical Illnesses Related to Stress?Back in 1967 two researchers, Thomas Holmes and Richard Rahe, developed the Social Readjustment Rating Scale, which assigns numerical values to the stresses that most people experience at some time in their lives (see Table 10-8 below). Answers given by a large sample of participants indicated that the most stressful event on the scale is the death of a spouse, which receives a score of 100 life change units (LCUs). Lower on the scale is retirement (45 LCUs), and still lower is a minor violation of the law (11 LCUs). This scale gave researchers a yardstick for measuring the total amount of stress a person faces over a period of time. If, for example, in the course of a year a woman started a new business (39 LCUs), sent her son off to college (29 LCUs), moved to a new house (20 LCUs), and had a close friend die (37 LCUs), her stress score for the year would be 125 LCUs, a considerable amount of stress for such a period of time.

|

Adults: Social Readjustment Rating Scale* |

|

|

1. |

Death of spouse |

|

2. |

Divorce |

|

3. |

Marital separation |

|

4. |

Jail term |

|

5. |

Death of close family member |

|

6. |

Personal injury or illness |

|

7. |

Marriage |

|

8. |

Fired at work |

|

9. |

Marital reconciliation |

|

10. |

Retirement |

|

11. |

Change in health of family member |

|

12. |

Pregnancy |

|

13. |

Sex difficulties |

|

14. |

Gain of new family member |

|

15. |

Business readjustment |

|

16. |

Change in financial state |

|

17. |

Death of close friend |

|

18. |

Change to different line of work |

|

19. |

Change in number of arguments with spouse |

|

20. |

Mortgage over $10,000 |

|

21. |

Foreclosure of mortgage or loan |

|

22. |

Change in responsibilities at work |

|

Students: Undergraduate Stress Questionnaire† |

|

|

1. |

Death (family member or friend) |

|

2. |

Had a lot of tests |

|

3. |

It’s finals week |

|

4. |

Applying to graduate school |

|

5. |

Victim of a crime |

|

6. |

Assignments in all classes due the same day |

|

7. |

Breaking up with boy/girlfriend |

|

8. |

Found out boy/girlfriend cheated on you |

|

9. |

Lots of deadlines to meet |

|

10. |

Property stolen |

|

11. |

You have a hard upcoming week |

|

12. |

Went into a test unprepared |

|

13. |

Lost something (especially wallet) |

|

14. |

Death of a pet |

|

15. |

Did worse than expected on test |

|

16. |

Had an interview |

|

17. |

Had projects, research papers due |

|

18. |

Did badly on a test |

|

19. |

Parents getting divorce |

|

20. |

Dependent on other people |

|

21. |

Having roommate conflicts |

|

22. |

Car/bike broke down, flat tire, etc. |

|

* Full scale has 43 items. (Reprinted from Journal of Psychosomatic Research, Vol 11, Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H., The Social Readjustment Rating Scale, 213- |

|

|

† Full scale has 83 items. (Information from: Crandall, C. S., Preisler, J. J., & Aussprung, J. (1992). Measuring life event stress in the lives of college students: The Undergraduate Stress Questionnaire (USQ). Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(6), 627– |

|

338

With this scale in hand, Holmes and Rahe (1989, 1967) examined the relationship between life stress and the onset of illness. They found that the LCU scores of sick people during the year before they fell ill were much higher than those of healthy people. If a person’s life changes totaled more than 300 LCUs over the course of a year, he or she was particularly likely to develop serious health problems.

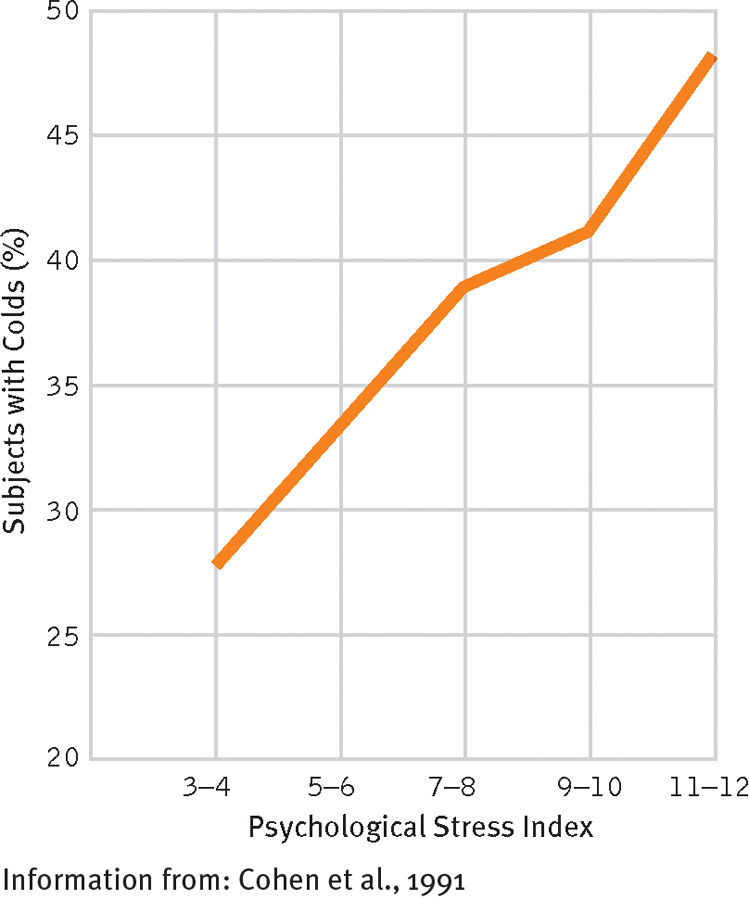

Using the Social Readjustment Rating Scale or similar scales, studies have since linked stresses of various kinds to a wide range of physical conditions, from trench mouth and upper respiratory infections to cancer (Baum et al., 2011; Rook et al., 2011) (see MediaSpeak below). Overall, the greater the amount of life stress, the greater the likelihood of illness (see Figure 10-5). Researchers even have found a relationship between traumatic stress and death. Widows and widowers, for example, display an increased risk of death during their period of bereavement (Moon et al., 2013; Möller et al., 2011; Young et al., 1963).

Stress and the common cold

In a landmark study, healthy participants were administered nasal drops containing common cold viruses. It was found that those participants who had recently had more stressors were much more likely to come down with a cold than participants who had had fewer recent stressors.

339

One shortcoming of Holmes and Rahe’s Social Readjustment Rating Scale is that it does not take into consideration the particular life stress reactions of specific populations. For example, in their development of the scale, the researchers sampled white Americans predominantly. Few of the respondents were African Americans or Hispanic Americans. But since their ongoing life experiences often differ in key ways, might not members of minority groups and white Americans differ in their stress reactions to various kinds of life events? Research indicates that indeed they do (Bennett & Olugbala, 2010; Johnson, 2010). One study found, for example, that African Americans experience greater stress than white Americans in response to a major personal injury or illness, a major change in work responsibilities, or a major change in living conditions (Komaroff et al., 1989, 1986). Similarly, studies have shown that women and men differ in their reactions to a number of life changes (Wang et al., 2007; Miller & Rahe, 1997).

Finally, college students may face stressors that are different from those listed in the Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Instead of having marital difficulties, being fired, or applying for a job, a college student may have trouble with a roommate, fail a course, or apply to graduate school. When researchers use special scales to measure life events in this population, they find the expected relationships between stressful events and illness (Anders et al., 2012; Hurst et al., 2012; Crandall et al., 1992) (see Table 10-8 again).

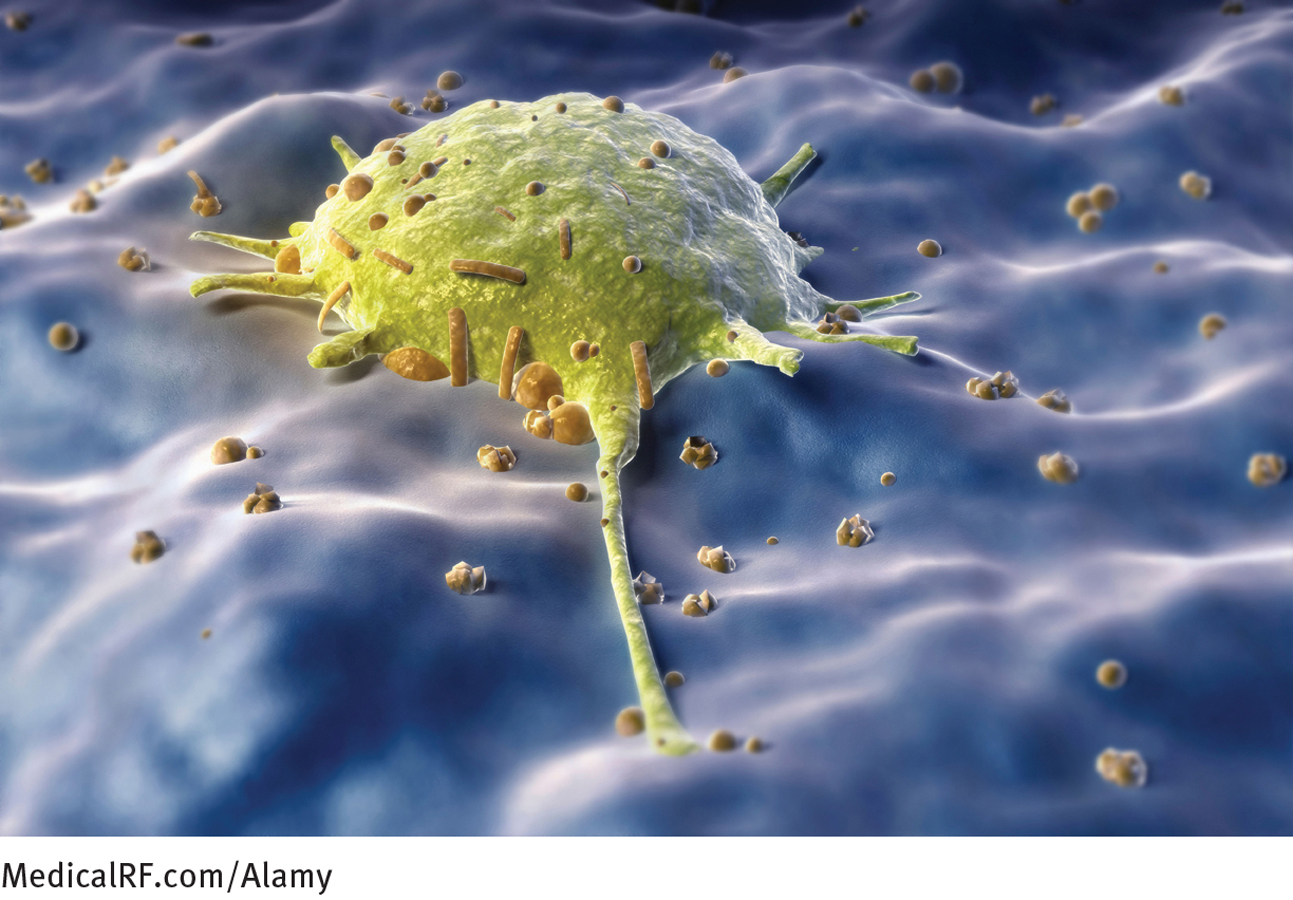

PsychoneuroimmunologyHow do stressful events result in a viral or bacterial infection? Researchers in an area of study called psychoneuroimmunology seek to answer this question by uncovering the links between psychosocial stress, the immune system, and health. The immune system is the body’s network of activities and cells that identify and destroy antigens—foreign invaders, such as bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites—

psychoneuroimmunology The study of the connections between stress, the body’s immune system, and illness.

psychoneuroimmunology The study of the connections between stress, the body’s immune system, and illness.

immune system The body’s network of activities and cells that identify and destroy antigens and cancer cells.

immune system The body’s network of activities and cells that identify and destroy antigens and cancer cells.

antigen A foreign invader of the body, such as a bacterium or virus.

antigen A foreign invader of the body, such as a bacterium or virus.

lymphocytes White blood cells that circulate through the lymph system and bloodstream, helping the body identify and destroy antigens and cancer cells.

lymphocytes White blood cells that circulate through the lymph system and bloodstream, helping the body identify and destroy antigens and cancer cells.

One group of lymphocytes, called helper T-

Researchers now believe that stress can interfere with the activity of lymphocytes, slowing them down and thus increasing a person’s susceptibility to viral and bacterial infections (Dhabhar, 2014, 2011). In a landmark study, investigator Roger Bartrop and his colleagues (1977) in New South Wales, Australia, compared the immune systems of 26 people whose spouses had died 8 weeks earlier with those of 26 matched control group participants whose spouses had not died. Blood samples revealed that lymphocyte functioning was much lower in the bereaved people than in the controls. Still other studies have shown slow immune functioning in people who are exposed to long-

340

MediaSpeak

When Doctors Discriminate

By Juliann Garey, The New York Times, August 10, 2013

The first time it was an ear, nose and throat doctor. I had an emergency visit for an ear infection, which was causing a level of pain I hadn’t experienced since giving birth. He looked at the list of drugs I was taking for my bipolar disorder and closed my chart.

“I don’t feel comfortable prescribing anything,” he said. “Not with everything else you’re on.” He said it was probably safe to take Tylenol and politely but firmly indicated it was time for me to go. The next day my eardrum ruptured and I was left with minor but permanent hearing loss.

Another time I was lying on the examining table when a gastroenterologist I was seeing for the first time looked at my list of drugs and shook her finger in my face. “You better get yourself together psychologically,” she said, “or your stomach is never going to get any better.” …

I was surprised when, after one of these run-

I never knew it until I started poking around, but this particular kind of discriminatory doctoring has a name. It’s called “diagnostic overshadowing.”

Can you think of reasons, other than diagnostic overshadowing, that people with severe psychological disorders might have poorer health and shorter life spans?

According to a review of studies done by the Institute of Psychiatry at King’s College, London, it happens a lot. As a result, people with a serious mental illness—

That is a problem, because if you are given one of these diagnoses you probably also suffer from one or more chronic physical conditions: though no one quite knows why, migraines, irritable bowel syndrome and mitral valve prolapse often go hand in hand with bipolar disorder….

It’s little wonder that many people with a serious mental illness don’t seek medical attention when they need it. As a result, many of us end up in emergency rooms—

Indeed, given my experience over the last two decades, I shouldn’t have been surprised by the statistics I found in … a review of studies published in 2006…. The take-

True, suicide is a big factor, accounting for 30 to 40 percent of early deaths. But 60 percent die of preventable or treatable conditions. First on the list is, unsurprisingly, cardiovascular disease. Two studies showed that patients with both a mental illness and a cardiovascular condition received about half the number of follow-

The report also contains a list of policy recommendations, including designating patients with serious mental illnesses as a high-

We can only hope that humanizing programs like this … become a requirement for all health care workers. Maybe then “first, do no harm” will apply to everyone, even the mentally ill.

August 11, 2013 “OPINION; When Doctors Discriminate” Carey, Juliann. From The New York Times, 8/11/2013 © 2013 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this Content without express written permission is prohibited.

341

These studies seem to be telling a remarkable story. During periods when healthy people happened to have unusual levels of stress, they remained healthy on the surface, but their stressors apparently slowed their immune systems so that they became susceptible to illness. If stress affects our capacity to fight off illness, it is no wonder that researchers have repeatedly found a relationship between life stress and illnesses of various kinds. But why and when does stress interfere with the immune system? Several factors influence whether stress will result in a slowdown of the system, including biochemical activity, behavioral changes, personality style, and degree of social support.

BIOCHEMICAL ACTIVITYExcessive activity of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine apparently contributes to slowdowns of the immune system. Remember from Chapter 6 that stress leads to increased activity by the sympathetic nervous system, including an increase in the release of norepinephrine throughout the brain and body. Research indicates that if stress continues for an extended time, norepinephrine eventually travels to receptors on certain lymphocytes and gives them an inhibitory message to stop their activity, thus slowing down immune functioning (Dhabhar, 2014; Groër et al., 2010; Lekander, 2002).

In a similar manner, corticosteroids—that is, cortisol and other so-

Recent research has further indicated that another action of the corticosteroids is to trigger an increase in the production of cytokines, proteins that bind to receptors throughout the body. At moderate levels of stress, the cytokines, another key player in the immune system, help combat infection. But as stress continues and more corticosteroids are released, the growing production and spread of cytokines lead to chronic inflammation throughout the body, contributing at times to heart disease, stroke, and other illnesses (Dhabhar, 2014; Brooks et al., 2011; Burg & Pickering, 2011).

BEHAVIORAL CHANGESStress may set in motion a series of behavioral changes that indirectly affect the immune system. Some people under stress may, for example, become anxious or depressed, perhaps even develop an anxiety or mood disorder. As a result, they may sleep badly, eat poorly, exercise less, or smoke or drink more—

PERSONALITY STYLEAccording to research, people who generally respond to life stress with optimism, constructive coping, and resilience—

BETWEEN THE LINES

The Immune System at Work

Marital Stress During and after marital spats, women typically release more stress hormones than men, and so have poorer immune functioning (Gouin et al., 2009; Kiecolt-

342

In related work, researchers have found a relationship between certain personality characteristics and a person’s ability to cope effectively with cancer (Baum et al., 2011; Floyd et al., 2011). They have found, for example, that patients with certain forms of cancer who display a helpless coping style and who cannot easily express their feelings, particularly anger, tend to have a poorer quality of life in the face of their disease than patients who do express their emotions. A few investigators have even suggested a relationship between personality and cancer outcome, but this claim has not been supported clearly by research (Pillay et al., 2014; Kern & Friedman, 2011; Urcuyo et al., 2005).

SOCIAL SUPPORTFinally, people who have few social supports and feel lonely tend to have poorer immune functioning in the face of stress than people who do not feel lonely (Hicks, 2014; Cohen, 2002). In a pioneering study, medical students were given the UCLA Loneliness Scale and then divided into “high” and “low” loneliness groups (Kiecolt-

Other studies have found that social support and affiliation may actually help protect people from stress, poor immune system functioning, and subsequent illness, or help speed up recovery from illness or surgery (Rook et al., 2011). Similarly, some studies have suggested that patients with certain forms of cancer who receive social support in their personal lives or supportive therapy often have better immune system functioning and more successful recoveries than patients without such supports (Dagan et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2010).

Psychological Treatments for Physical Disorders

As clinicians have discovered that stress and related psychological and sociocultural factors may contribute to physical disorders, they have applied psychological treatments to more and more medical problems. The most common of these interventions are relaxation training, biofeedback, meditation, hypnosis, cognitive interventions, support groups, and therapies to increase awareness and expression of emotions. The field of treatment that combines psychological and physical approaches to treat or prevent medical problems is known as behavioral medicine.

behavioral medicine A field that combines psychological and physical interventions to treat or prevent medical problems.

behavioral medicine A field that combines psychological and physical interventions to treat or prevent medical problems.

343

Relaxation TrainingAs you saw in Chapter 5, people can be taught to relax their muscles at will, a process that sometimes reduces feelings of anxiety. Given the positive effects of relaxation on anxiety and the nervous system, clinicians believe that relaxation training can help prevent or treat medical illnesses that are related to stress.

Relaxation training, often in combination with medication, has been widely used in the treatment of high blood pressure (Moffatt et al., 2010). It has also been of some help in treating headaches, insomnia, asthma, diabetes, pain, certain vascular diseases, and the undesirable effects of certain cancer treatments (Gagnon et al., 2013; Nezu et al., 2011).

BiofeedbackAs you also saw in Chapter 5, patients given biofeedback training are connected to machinery that gives them continuous readings about their involuntary body activities. This information enables them gradually to gain control over those activities. Somewhat helpful in the treatment of anxiety disorders, the procedure has also been applied to a growing number of physical disorders.

In a classic study, electromyograph (EMG) feedback was used to treat 16 patients who had facial pain caused in part by tension in their jaw muscles (Dohrmann & Laskin, 1978). In an EMG procedure, electrodes are attached to a person’s muscles so that the muscle contractions are detected and converted into an audible tone (see page 143). Changes in the pitch and volume of the tone indicate changes in muscle tension. After “listening” to EMG feedback repeatedly, the 16 patients in this study learned how to relax their jaw muscles at will and later reported that they had less facial pain.

EMG feedback has also been used successfully in the treatment of headaches and muscular disabilities caused by strokes or accidents. Still other forms of biofeedback training have been of some help in the treatment of heartbeat irregularities, asthma, high blood pressure, stuttering, and pain (Freitag, 2013; Young & Kemper, 2013; Stokes & Lappin, 2010).

MeditationAlthough meditation has been practiced since ancient times, Western health care professionals have only recently become aware of its effectiveness in relieving physical distress. Meditation is a technique of turning one’s concentration inward, achieving a slightly changed state of consciousness, and temporarily ignoring all stressors. In the most common approach, meditators go to a quiet place, assume a comfortable posture, utter or think a particular sound (called a mantra) to help focus their attention, and allow their mind to turn away from all outside thoughts and concerns. Many people who meditate regularly report feeling more peaceful, engaged, and creative. Meditation has been used to help manage pain and to treat high blood pressure, heart problems, asthma, skin disorders, diabetes, insomnia, and even viral infections (Manchanda & Madan, 2014; Stein, 2003; Andresen, 2000).

One form of meditation that has been used in particular by patients suffering from severe pain is mindfulness meditation (Barker, 2014; Kabat-

HypnosisAs you saw in Chapter 1, people who undergo hypnosis are guided by a hypnotist into a sleeplike, suggestible state during which they can be directed to act in unusual ways, feel unusual sensations, remember seemingly forgotten events, or forget remembered events. With training, some people are even able to induce their own hypnotic state (self-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Gender and the Heart

According to research, women wait longer than men to go to an emergency room when having a heart attack.

Women are twice as likely as men to die within the first few weeks after suffering a heart attack.

Women who have had a heart attack experience significantly poorer emotional health than women who have never had a heart attack.

Men who have had a heart attack experience slightly poorer emotional health than men who have never had a heart attack.

(Information from: Besal & Liu, 2013; WhF, 2011)

344

Hypnosis seems to be particularly helpful in the control of pain (Jensen et al., 2014, 2011). One case study describes a patient who underwent dental surgery under hypnotic suggestion: After a hypnotic state was induced, the dentist suggested to the patient that he was in a pleasant and relaxed setting listening to a friend describe his own success at undergoing similar dental surgery under hypnosis. The dentist then proceeded to perform a successful 25-

Cognitive InterventionsPeople with physical ailments have sometimes been taught new attitudes or cognitive responses toward their ailments as part of treatment (Hampel et al., 2014; Syrjala et al., 2014; Diefenbach et al., 2010). For example, an approach called self-

Support Groups and Emotion ExpressionIf anxiety, depression, anger, and the like contribute to a person’s physical ills, interventions to reduce these negative emotions should help reduce the ills. Thus it is not surprising that some medically ill people have profited from support groups and from therapies that guide them to become more aware of and express their emotions and needs (Bell et al., 2010; Hsu et al., 2010; Antoni, 2005). Research suggests that the discussion, or even the writing down, of past and present emotions or upsets may help improve a person’s health, just as it may help one’s psychological functioning (Kelly & Barry, 2010; Smyth & Pennebaker, 2001). In one study, asthma and arthritis patients who wrote down their thoughts and feelings about stressful events for a handful of days showed lasting improvements in their conditions. Similarly, stress-

345

BETWEEN THE LINES

Strictly a Coincidence?

On February 17, 1673, French actor-

Combination ApproachesStudies have found that the various psychological interventions for physical problems tend to be equally effective (Devineni & Blanchard, 2005). Relaxation and biofeedback training, for example, are equally helpful (and more helpful than placebos) in the treatment of high blood pressure, headaches, and asthma. Psychological interventions are, in fact, often most helpful when they are combined with other psychological interventions and with medical treatments (Jensen et al., 2014, 2011; Hembree & Foa, 2010). In a classic study, ulcer patients who were given relaxation, self-

Clearly, the treatment picture for physical illnesses has been changing dramatically. While medical treatments continue to dominate, today’s medical practitioners are traveling a course far removed from that of their counterparts in centuries past.