12.2 Stimulants

Stimulants are substances that increase the activity of the central nervous system, resulting in increased blood pressure and heart rate, more alertness, and sped-

Cocaine

Cocaine—the central active ingredient of the coca plant, found in South America—

cocaine An addictive stimulant obtained from the coca plant. It is the most powerful natural stimulant known.

cocaine An addictive stimulant obtained from the coca plant. It is the most powerful natural stimulant known.

Sherlock Holmes took his bottle from the corner of the mantelpiece, and his hypodermic syringe from its neat morocco case. With his long white nervous fingers, he adjusted the delicate needle and rolled back his left shirtcuff. For some little time his eyes rested thoughtfully upon the sinewy forearm and wrist, all dotted and scarred with innumerable puncture-

Three times a day for many months I had witnessed this performance, but custom had not reconciled my mind to it….

“Which is it today,” I asked, “morphine or cocaine?”

He raised his eyes languidly from the old black-

393

“It is cocaine,” he said, “a seven-

“No, indeed,” I answered brusquely. “My constitution has not got over the Afghan campaign yet. I cannot afford to throw any extra strain upon it.”

He smiled at my vehemence. “Perhaps you are right, Watson,” he said. “I suppose that its influence is physically a bad one. I find it, however, so transcendently stimulating and clarifying to the mind that its secondary action is a matter of small moment.”

“But consider!” I said earnestly. “Count the cost! Your brain may, as you say, be roused and excited, but it is a pathological and morbid process which involves increased tissue-

(Doyle, 1938, pp. 91-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Cocaine Alert

Cocaine accounts for more drug treatment admissions than any other drug (Hart & Ksir, 2014; SAMHSA, 2014).

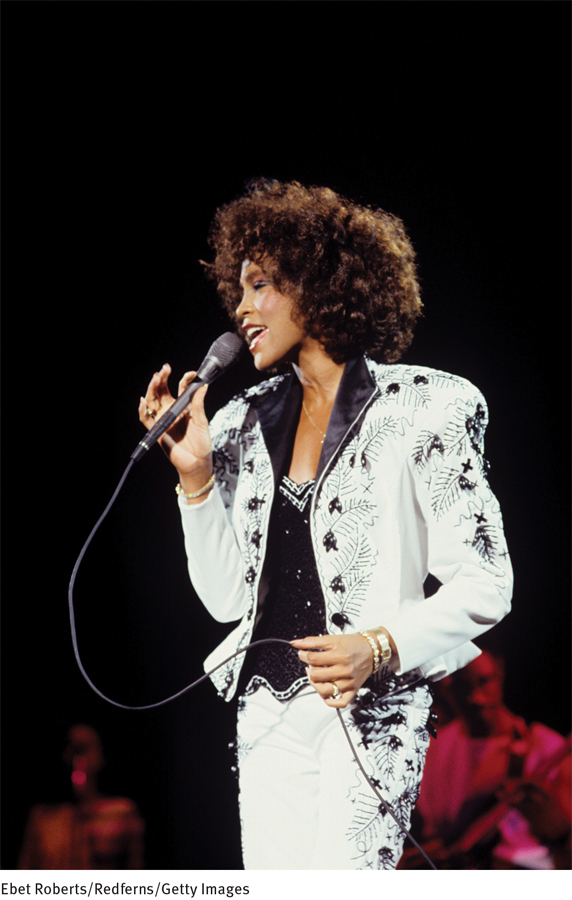

For years people believed that cocaine posed few problems aside from intoxication and, on occasion, temporary psychosis (see Table 12-3). Like Sherlock Holmes, many felt that the benefits outweighed the costs. Only later did researchers come to appreciate its many dangers (Haile, 2012). Their insights came after society witnessed a dramatic surge in the drug’s popularity and in problems related to its use. In the early 1960s, an estimated 10,000 people in the United States had tried cocaine. Today 28 million people have tried it, and 1.6 million—

|

Potential Intoxication |

Addiction Potential |

Risk of Organ Damage or Death |

Risk of Severe Social or Economic Consequences |

Risk of Severe or Long- |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Opioids |

High |

High |

Moderate |

High |

Low to moderate |

|

Sedative- Barbiturates Benzodiazepines |

Moderate Moderate |

Moderate to high Moderate |

Moderate to high Low |

Moderate to high Low |

Low Low |

|

Stimulants (cocaine, amphetamines) |

High |

High |

Moderate |

Low to moderate |

Moderate to high |

|

Alcohol |

High |

Moderate |

High |

High |

High |

|

Cannabis |

High |

Low to moderate |

Low |

Low to moderate |

Low |

|

Mixed drugs |

High |

High |

High |

High |

High |

|

Information from: Hart & Ksir, 2014; APA, 2013; Hart et al., 2010. |

|||||

Cocaine brings on a euphoric rush of well-

Cocaine apparently produces these effects largely by increasing supplies of the neurotransmitter dopamine at key neurons throughout the brain (Haile, 2012; Kosten et al., 2008). Excessive amounts of dopamine travel to receiving neurons throughout the central nervous system and overstimulate them. Cocaine appears to also increase the activity of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin in some areas of the brain (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Haile, 2012).

394

InfoCentral

SMOKING, TOBACCO, AND NICOTINE

Around 27% percent of all Americans over the age of 11 regularly smoke tobacco—

WHO SMOKES REGULARLY IN THE UNITED STATES?

395

High doses of the drug produce cocaine intoxication, whose symptoms are poor muscle coordination, grandiosity, bad judgment, anger, aggression, compulsive behavior, anxiety, and confusion. Some people have hallucinations, delusions, or both, a condition called cocaine-

A young man described how, after free-

(Allen, 1985, pp. 19–

As the stimulant effects of cocaine subside, the user goes through a depression-

Ingesting CocaineIn the past, cocaine use and impact were limited by the drug’s high cost. Moreover, cocaine was usually snorted, a form of ingestion that has less powerful effects than either smoking or injection (Haile, 2012). Since 1984, however, the availability of newer, more powerful, and sometimes cheaper forms of cocaine has produced an enormous increase in the use of the drug. For example, many people now ingest cocaine by freebasing, a technique in which the pure cocaine basic alkaloid is chemically separated, or “freed,” from processed cocaine, vaporized by heat from a flame, and inhaled through a pipe.

freebase A technique for ingesting cocaine in which the pure cocaine basic alkaloid is chemically separated from processed cocaine, vaporized by heat from a flame, and inhaled with a pipe.

freebase A technique for ingesting cocaine in which the pure cocaine basic alkaloid is chemically separated from processed cocaine, vaporized by heat from a flame, and inhaled with a pipe.

Millions more people use crack, a powerful form of freebase cocaine that has been boiled down into crystalline balls. It is smoked with a special pipe and makes a crackling sound as it is inhaled (hence the name). Crack is sold in small quantities at a fairly low cost, which has resulted in crack epidemics among people who previously could not have afforded cocaine, primarily those in poor, urban areas (Acosta et al., 2011, 2005). Around 1.1 percent of high school seniors report having used crack within the past year, down from a peak of 2.7 percent in 1999 (Johnston et al., 2014).

crack A powerful, ready-

crack A powerful, ready-

What Are the Dangers of Cocaine?Aside from cocaine’s harmful effects on behavior, cognition, and emotion, the drug poses serious physical dangers (Paczynski & Gold, 2011). The growth in the use of the powerful forms of cocaine has caused the annual number of cocaine-

The greatest danger of cocaine use is an overdose. Excessive doses have a strong effect on the respiratory center of the brain, at first stimulating it and then depressing it to the point where breathing may stop. Cocaine can also create major, even fatal, heart irregularities or brain seizures that bring breathing or heart functioning to a sudden stop (Acosta et al., 2011, 2005). In addition, pregnant women who use cocaine run the risk of having a miscarriage and of having children with predispositions to later drug use and with abnormalities in immune functioning, attention and learning, thyroid size, and dopamine and serotonin activity in the brain (Minnes et al., 2014; Hart & Ksir, 2014; Kosten et al., 2008).

396

Amphetamines

Amphetamines are stimulant drugs that are manufactured in the laboratory. Some common examples are amphetamine (Benzedrine), dextro-

amphetamine A stimulant drug that is manufactured in the laboratory.

amphetamine A stimulant drug that is manufactured in the laboratory.

Amphetamines are most often taken in pill or capsule form, although some people inject the drugs intravenously or smoke them for a quicker, more powerful effect. Like cocaine, amphetamines increase energy and alertness and reduce appetite when taken in small doses; produce a rush, intoxication, and psychosis in high doses; and cause an emotional letdown as they leave the body. Also like cocaine, amphetamines stimulate the central nervous system by increasing the release of the neurotransmitters dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin throughout the brain, although the actions of amphetamines differ somewhat from those of cocaine (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Haile, 2012).

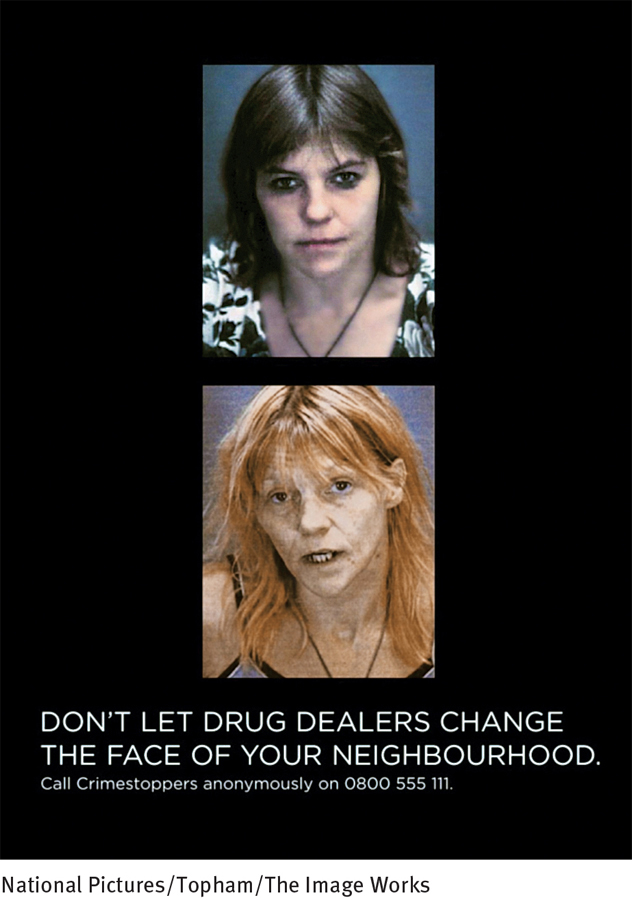

One kind of amphetamine, methamphetamine (nicknamed crank), has surged in popularity in recent years and so warrants special focus. Almost 6 percent of all people over the age of 11 in the United States have used methamphetamine at least once. Around 0.2 percent use it currently (NSDUH, 2013). It is available in the form of crystals (also known by the street names ice and crystal meth), which users smoke.

methamphetamine A powerful amphetamine drug that has surged in popularity in recent years, posing major health and law enforcement problems.

methamphetamine A powerful amphetamine drug that has surged in popularity in recent years, posing major health and law enforcement problems.

Most of the nonmedical methamphetamine in the United States is made in small “stovetop laboratories,” which typically operate for a few days in a remote area and then move on to a new—

Since 1989, when the media first began reporting about the dangers of smoking methamphetamine crystals, the rise in usage has been dramatic. Until recently, it had been much more prevalent in western parts of the United States, but its use has now spread east as well. Methamphetamine-

Methamphetamine is about as likely to be used by women as men. Around 40 percent of current users are women (NSDUH, 2013). The drug is particularly popular today among biker gangs, rural Americans, and urban gay communities and has gained wide use as a “club drug,” the term for those drugs that regularly find their way to all night dance parties, or “raves” (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Hopfer, 2011).

Like other kinds of amphetamines, methamphetamine increases activity of the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, producing increased arousal, attention, and related effects (Acosta et al., 2011, 2005; Dean & London, 2010). It can have serious negative effects on a user’s physical, mental, and social life. Of particular concern is that it damages nerve endings, a problem called neurotoxicity. But users focus more on methamphetamine’s immediate positive impact, including perceptions by many that it makes them feel hypersexual and uninhibited (Washton & Zweben, 2008; Jefferson, 2005).

397

Stimulant Use Disorder

Regular use of either cocaine or amphetamines may lead to stimulant use disorder. The stimulant comes to dominate the person’s life, and the person may remain under the drug’s effects much of each day and function poorly in social relationships and at work. Regular stimulant use may also cause problems in short-

Caffeine

Caffeine is the world’s most widely used stimulant. Around 80 percent of the world’s population consumes it daily. Most of this caffeine is taken in the form of coffee (from the coffee bean); the rest is consumed in tea (from the tea leaf), cola (from the kola nut), so-

caffeine The world’s most widely used stimulant, most often consumed in coffee.

caffeine The world’s most widely used stimulant, most often consumed in coffee.

Around 99 percent of ingested caffeine is absorbed by the body and reaches its peak concentration within an hour. It acts as a stimulant of the central nervous system, again producing a release of the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine in the brain (Advokat et al., 2014; Cauli & Morelli, 2005). Thus it raises a person’s arousal and motor activity and reduces fatigue. It can also disrupt mood, fine motor movement, and reaction time and may interfere with sleep (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Juliano, Anderson, & Griffiths, 2011; Judelson et al., 2005). At high doses, it increases gastric acid secretions in the stomach and the rate of breathing.

More than two to three cups of brewed coffee (250 milligrams of caffeine) can produce caffeine intoxication, which may include such symptoms as restlessness, nervousness, anxiety, stomach disturbances, twitching, and a faster heart rate (Juliano et al., 2011; Paton & Beer, 2001). Doses larger than 10 grams of caffeine (about 100 cups of coffee) can cause grand mal seizures and fatal respiratory failure.

Many people who suddenly stop or cut back on their usual intake of caffeine—

BETWEEN THE LINES

Energy drinks and young teens

Around 30 percent of middle school students report consuming energy drinks. Around 60 percent consume soft drinks daily.

(Information from Terry-

Although DSM-

398

Investigators often assess caffeine’s impact by measuring coffee consumption, yet coffee also contains other chemicals that may be dangerous to a person’s health. Although some early studies hinted at links between caffeine and cancer (particularly pancreatic cancer), the evidence is not conclusive (Hart & Ksir, 2014; Juliano et al., 2011). On the other hand, studies do suggest that there may be correlations between high doses of caffeine and heart rhythm irregularities (arrhythmias), high cholesterol levels, and risk of heart attacks (Hart & Ksir, 2014). And some, but not all, studies raise the possibility that very high doses of caffeine during pregnancy may increase the risk of miscarriage (Brent et al., 2011; Weng et al., 2008). As public awareness of these possible health risks has increased, caffeine consumption has declined and the consumption of decaffeinated drinks has increased over the past few decades. There are, however, indications that caffeine consumption may currently be on the rise once again.