16.2 “Dramatic” Personality Disorders

The cluster of “dramatic” personality disorders includes the antisocial, borderline, histrionic, and narcissistic personality disorders. The behaviors of people with these problems are so dramatic, emotional, or erratic that it is almost impossible for them to have relationships that are truly giving and satisfying.

These personality disorders are more commonly diagnosed than the others. However, only the antisocial and borderline personality disorders have received much study, partly because they create so many problems for other people. The causes of the disorders, like those of the odd personality disorders, are not well understood. Treatments range from ineffective to moderately effective.

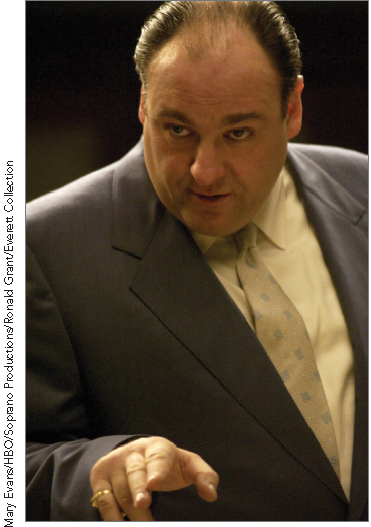

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Sometimes described as “psychopaths” or “sociopaths,” people with antisocial personality disorder persistently disregard and violate others’ rights (APA, 2013). Aside from substance use disorders, this is the disorder most closely linked to adult criminal behavior. DSM-

antisocial personality disorder A personality disorder marked by a general pattern of disregard for and violation of other people’s rights.

antisocial personality disorder A personality disorder marked by a general pattern of disregard for and violation of other people’s rights.

Robert Hare, a leading researcher of antisocial personality disorder, recalls an early professional encounter with a prison inmate named Ray:

In the early 1960s, I found myself employed as the sole psychologist at the British Columbia Penitentiary…. I wasn’t in my office for more than an hour when my first “client” arrived. He was a tall, slim, dark-

Without waiting for an introduction, the inmate—

Eager to begin work as a genuine psychotherapist, I asked him to tell me about it. In response, he pulled out a knife and waved it in front of my nose, all the while smiling and maintaining that intense eye contact.

Once he determined that I wasn’t going to push the button, he explained that he intended to use the knife not on me but on another inmate who had been making overtures to his “protégé,” a prison term for the more passive member of a homosexual pairing. Just why he was telling me this was not immediately clear, but I soon suspected that he was checking me out, trying to determine what sort of a prison employee I was….

From that first meeting on, Ray managed to make my eight-

530

Once out of “the hole,” Ray appeared in my office as if nothing had happened and asked for a transfer from the kitchen to the auto shop—

Soon afterward I decided to leave the prison to pursue a Ph.D. in psychology, and about a month before I left Ray almost persuaded me to ask my father, a roofing contractor, to offer him a job as part of an application for parole.

Ray had an incredible ability to con not just me but everybody. He could talk, and lie, with a smoothness and a directness that sometimes momentarily disarmed even the most experienced and cynical of the prison staff. When I met him he had a long criminal record behind him (and, as it turned out, ahead of him); about half his adult life had been spent in prison, and many of his crimes had been violent…. He lied endlessly, lazily, about everything, and it disturbed him not a whit whenever I pointed out something in his file that contradicted one of his lies. He would simply change the subject and spin off in a different direction. Finally convinced that he might not make the perfect job candidate in my father’s firm, I turned down Ray’s request—

Before I left the prison for the university, I took advantage of the prison policy of letting staff have their cars repaired in the institution’s auto shop—

With all our possessions on top of the car and our baby in a plywood bed in the backseat, my wife and I headed for Ontario. The first problems appeared soon after we left Vancouver, when the motor seemed a bit rough. Later, when we encountered some moderate inclines, the radiator boiled over. A garage mechanic discovered ball bearings in the carburetor’s float chamber; he also pointed out where one of the hoses to the radiator had clearly been tampered with. These problems were repaired easily enough, but the next one, which arose while we were going down a long hill, was more serious. The brake pedal became very spongy and then simply dropped to the floor—

(Hare, 1993)

BETWEEN THE LINES

Previous Identity

Antisocial personality disorder was referred to as “moral insanity” during the nineteenth century.

Like Ray, people with antisocial personality disorder lie repeatedly (APA, 2013). Many cannot work consistently at a job; they are absent frequently and are likely to quit their jobs altogether (Hengartner et al., 2014). Usually they are also careless with money and frequently fail to pay their debts. They are often impulsive, taking action without thinking of the consequences (Millon, 2011). Correspondingly, they may be irritable, aggressive, and quick to start fights. Many travel from place to place.

531

Recklessness is another common trait: people with antisocial personality disorder have little regard for their own safety or for that of others, even their children. They are self-

How do various institutions in our society—

Surveys indicate that 3.6 percent of adults in the United States meet the criteria for antisocial personality disorder (Sansone & Sansone, 2011). The disorder is as much as four times more common among men than women.

Because people with this disorder are often arrested, researchers frequently look for people with antisocial patterns in prison populations (Pondé et al., 2014; Black et al., 2010). It is estimated that at least 40 percent of people in prison meet the diagnostic criteria for this disorder (Naidoo & Mkize, 2012). Among men in urban jails, the antisocial personality pattern has been linked strongly to past arrests for crimes of violence (De Matteo et al., 2005). The criminal behavior of many people with this disorder declines after the age of 40; some, however, continue their criminal activities throughout their lives (APA, 2013).

|

Group Attacked |

Number of Reported Incidents |

|

Racial/ethnic groups |

4,119 |

|

LGBT* groups |

1,318 |

|

Religious groups |

1,166 |

|

Groups with disability |

102 |

|

*Widely accepted acronym for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender people |

|

|

Information from: U.S. Department of Justice, Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2013, 2012 |

|

Studies and clinical observations also indicate that people with antisocial personality disorder have higher rates of alcoholism and other substance use disorders than do the rest of the population (Brook et al., 2014; Reese et al., 2010). Perhaps intoxication and substance misuse help trigger the development of antisocial personality disorder by loosening a person’s inhibitions. Perhaps this personality disorder somehow makes a person more prone to abuse substances. Or perhaps antisocial personality disorder and substance use disorders both have the same cause, such as a deep-

532

It appears that children with conduct disorder and an accompanying attention-

How Do Theorists Explain Antisocial Personality Disorder?Explanations of antisocial personality disorder come from the psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive, and biological models. As with many other personality disorders, psychodynamic theorists propose that this one begins with an absence of parental love during infancy, leading to a lack of basic trust (Meloy & Yakeley, 2010; Sperry, 2003). In this view, some children—

Many behavioral theorists have suggested that antisocial symptoms may be learned through modeling, or imitation (Gaynor & Baird, 2007). As evidence, they point to the higher rate of antisocial personality disorder found among the parents of people with this disorder (APA, 2013; Paris,2001). Other behaviorists have suggested that some parents unintentionally teach antisocial behavior by regularly rewarding a child’s aggressive behavior (Kazdin, 2005). When the child misbehaves or becomes violent in reaction to the parents’ requests or orders, for example, the parents may give in to restore peace. Without meaning to, they may be teaching the child to be stubborn and perhaps even violent.

Can you point to attitudes and events in today’s world that may trivialize people’s needs? What impact might they have on individual functioning?

533

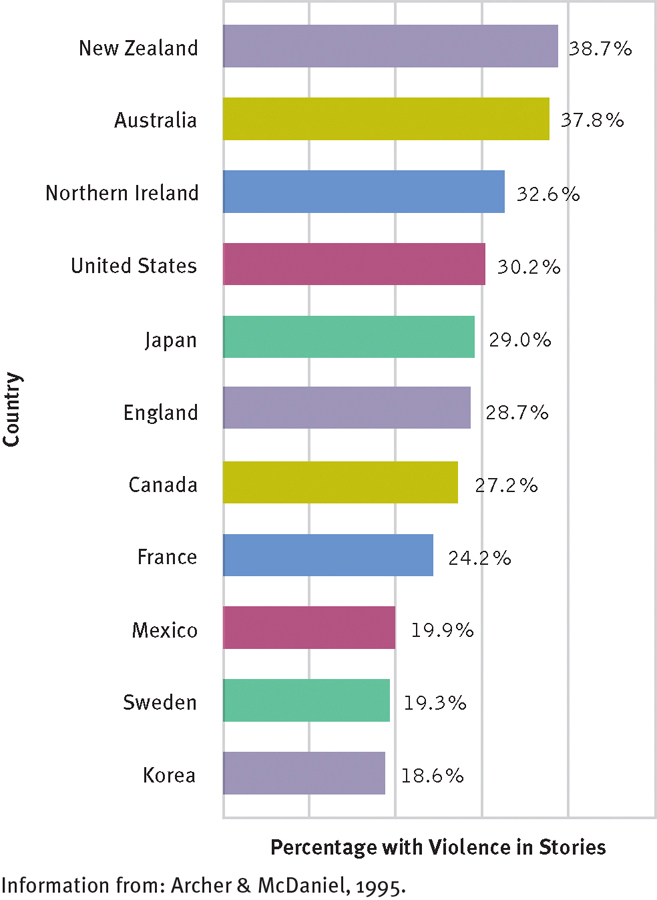

The cognitive view says that people with antisocial personality disorder hold attitudes that trivialize the importance of other people’s needs (Elwood et al., 2004). Such a philosophy of life, some theorists suggest, may be far more common in our society than people recognize (see Figure 16-3). Cognitive theorists further propose that people with this disorder have genuine difficulty recognizing points of view or feelings other than their own (Herpertz & Bertsch, 2014).

Are some cultures more antisocial than others?

In a cross-

Finally, studies suggest that biological factors may play an important role in antisocial personality disorder. Researchers have found that antisocial people, particularly those who are highly impulsive and aggressive, have lower serotonin activity than other people (Thompson, Ramos, & Willett, 2014; Patrick, 2007). As you’ll recall (see page 300), both impulsivity and aggression also have been linked to low serotonin activity in other kinds of studies, so the presence of this biological factor in people with antisocial personality disorder is not surprising.

Other studies indicate that individuals with this disorder display deficient functioning in their frontal lobes, particularly in the prefrontal cortex (Liu et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2014). Among other duties, this brain region helps people to plan and execute realistic strategies and to have personal characteristics such as sympathy, judgment, and empathy. These are, of course, all qualities found wanting in people with antisocial personality disorder.

In yet another line of research, investigators have found that people with antisocial personality disorder often feel less anxiety than other people, and so lack a key ingredient for learning (Blair et al., 2005). This would help explain why they have so much trouble learning from negative life experiences or tuning in to the emotional cues of others. Why should people with antisocial personality disorder experience less anxiety than other people? The answer may lie once again in the biological realm. Research participants with the disorder often respond to warnings or expectations of stress with low brain and bodily arousal, such as slow autonomic arousal and slow EEG waves (Thompson et al., 2014; Perdeci et al., 2010). Perhaps because of the low arousal, they easily tune out threatening or emotional situations, and so are unaffected by them.

It could also be argued that because of their physical underarousal, people with antisocial personality disorder would be more likely than other people to take risks and seek thrills. That is, they may be drawn to antisocial activity precisely because it meets an underlying biological need for more excitement and arousal. In support of this idea, as you read earlier, antisocial personality disorder often goes hand in hand with sensation-

Treatments for Antisocial Personality DisorderTreatments for people with antisocial personality disorder are typically ineffective (Millon, 2011; Meloy & Yakeley, 2010). Major obstacles to treatment include the individuals’ lack of conscience, desire to change, or respect for therapy (Colli et al., 2014; Kantor, 2006). Most of those in therapy have been forced to participate by an employer, their school, or the law, or they come to the attention of therapists when they also develop another psychological disorder (Agronin, 2006).

534

PsychWatch

Mass Murders: Where Does Such Violence Come From?

On December 14, 2012, a young man entered the Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, and killed 26 people—

What do we know about mass killings? We know they involve, by definition, the murder of four or more people in the same location and at around the same time. FBI records also indicate that, on average, mass killings occur in the United States every 2 weeks, 75 percent of them feature a lone killer, 67 percent involve the use of guns, and most are committed by males (Hoyer & Heath, 2012).

We also know that despite appearances, the number of mass killings is not on the rise overall (O’Neill, 2012). What is increasing, however, are certain kinds of mass killings. So-

Theorists have suggested a number of factors to help explain pseudocommando, autogenetic, and other mass killings, including the availability of guns, bullying behavior, substance abuse, the proliferation of violent media and video games, dysfunctional homes, contagion effects, and mental illness. In fact, regardless of one’s position on gun control, media violence, or the like, almost everyone, including most clinicians, believes that mass killers typically suffer from a mental disorder (Archer, 2012). Which mental disorder? On this, there is little agreement. Each of the following has been suggested:

Antisocial, borderline, paranoid, or schizotypal personality disorder

Schizophrenia or severe bipolar disorder

Intermittent explosive disorder—

an impulse- control disorder featuring repeated, unprovoked verbal and/or behavioral outbursts (Coccaro, 2012) Severe disorder of mood, stress, or anxiety

Although these and yet other disorders have been proposed, none has received clear support in the limited research conducted on mass killings. On the other hand, several variables have emerged as a common denominator across the various studies: severe feelings of anger and resentment, feelings of being persecuted or grossly mistreated, and desires for revenge (Knoll, 2010). That is, regardless of which psychological disorder a mass killer may display, he usually is driven by this set of feelings. For a growing number of clinical researchers, this repeated finding suggests that research should focus less on diagnosis and much more on identifying and understanding these particular feelings.

Clearly, clinical research must expand its focus on this area of enormous social concern. Granted it is a difficult problem to investigate, partly because so few mass killers survive their crimes, but the clinical field has managed to gather useful insights about other elusive areas. And, indeed, in the aftermath of the horrific massacre of so many innocent children in the Newtown shooting rampage, a wave of heightened determination and commitment seems to have seized the clinical community (Archer, 2012).

535

BETWEEN THE LINES

Character Ingestion

As late as the Victorian era, many English parents believed babies absorbed personality and moral uprightness as they took in milk. Thus, if a mother could not nurse, it was important to find a wet nurse of good character

(Asimov, 1997)

Some cognitive therapists try to guide clients with antisocial personality disorder to think about moral issues and about the needs of other people (Beck & Weishaar, 2011; Weishaar & Beck, 2006; Beck et al., 2004). In a similar vein, a number of hospitals and prisons have tried to create a therapeutic community for people with this disorder, a structured environment that teaches responsibility toward others (Harris & Rice, 2006). Some patients seem to profit from such approaches, but it appears that most do not. In recent years, clinicians have also used psychotropic medications, particularly atypical antipsychotic drugs, to treat people with antisocial personality disorder. Some report that these drugs help reduce certain features of the disorder, but systematic studies of this claim are still needed (Brown et al., 2014; Thompson et al., 2014; Silk & Jibson, 2010).

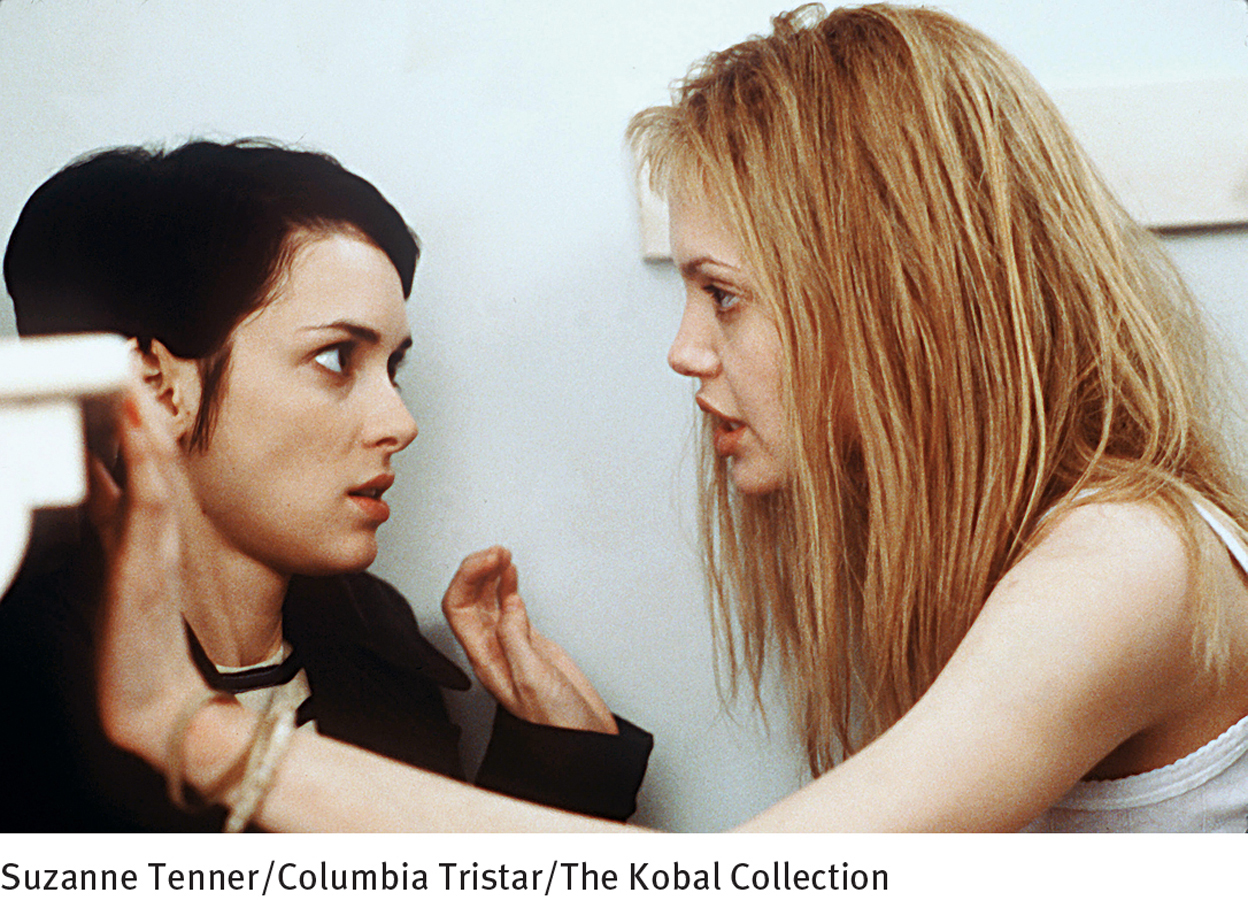

Borderline Personality Disorder

People with borderline personality disorder display great instability, including major shifts in mood, an unstable self-

borderline personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by repeated instability in interpersonal relationships, self-

borderline personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by repeated instability in interpersonal relationships, self-

Ellen Farber, a 35-

She attributed her increasing symptoms to financial difficulties. Ms. Farber had been fired from her job two weeks before…. She claimed it was because she “owed a small amount of money.” When asked to be more specific, she reported owing $150,000 to her former employers and another $100,000 to various local banks…. From age 30 to age 33, she had used her employer’s credit cards to finance weekly “buying binges,” accumulating the $150,000 debt. She … reported that spending money alleviated her chronic feelings of loneliness, isolation, and sadness. Experiencing only temporary relief, every few days she would impulsively buy expensive jewelry, watches, or multiple pairs of the same shoes….

In addition to lifelong feelings of emptiness, Ms. Farber described chronic uncertainty about what she wanted to do in life and with whom she wanted to be friends. She had many brief, intense relationships with both men and women, but her quick temper led to frequent arguments and even physical fights. Although she had always thought of her childhood as happy and carefree, when she became depressed, she began to recall [being abused verbally and physically by her mother].

(Spitzer et al., 1994, pp. 395–

Like Ellen Farber, people with borderline personality disorder swing in and out of very depressive, anxious, and irritable states that last anywhere from a few hours to a few days or more (see Table 16-3 below). Their emotions seem to be always in conflict with the world around them. They are prone to bouts of anger, which sometimes result in physical aggression and violence (Scott et al., 2014). Just as often, however, they direct their impulsive anger inward and inflict bodily harm on themselves. Many seem troubled by deep feelings of emptiness.

|

|

Cluster |

Similar Disorders |

Responsiveness to Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Paranoid |

Odd |

Schizophrenia; delusional disorder |

Modest |

|

Schizoid |

Odd |

Schizophrenia; delusional disorder |

Modest |

|

Schizotypal |

Odd |

Schizophrenia; delusional disorder |

Modest |

|

Antisocial |

Dramatic |

Conduct disorder |

Poor |

|

Borderline |

Dramatic |

Depressive disorder; bipolar disorder |

Moderate |

|

Histrionic |

Dramatic |

Somatic symptom disorder; depressive disorder |

Modest |

|

Narcissistic |

Dramatic |

Cyclothymic disorder (mild bipolar disorder) |

Poor |

|

Avoidant |

Anxious |

Social anxiety disorder |

Moderate |

|

Dependent |

Anxious |

Separation anxiety disorder; Moderatedepressive |

disorder |

|

Obsessive- |

Anxious |

Obsessive- |

Moderate |

536

Borderline personality disorder is a complex disorder, and it is fast becoming one of the more common conditions seen in clinical practice. Many of the patients who come to mental health emergency rooms are people with this disorder who have intentionally hurt themselves. Their impulsive, self-

Suicidal threats and actions are also common (Amore et al., 2014; Zimmerman et al., 2014; Leichsenring et al., 2011). Studies suggest that around 75 percent of people with borderline personality disorder attempt suicide at least once in their lives; as many as 10 percent actually commit suicide. It is common for people with this disorder to enter clinical treatment by way of the emergency room after a suicide attempt.

537

BETWEEN THE LINES

Whither “Borderline”?

In 1938 the term “borderline” was introduced by psychoanalyst Adolph Stern. He used it to describe patients who were more disturbed than “neurotic” patients, yet not psychotic (Bateman, 2011; Stern, 1938). The term has since evolved to its present usage.

People with borderline personality disorder frequently form intense, conflict-

People with borderline personality disorder typically have dramatic identity shifts. Because of this unstable sense of self, their goals, aspirations, friends, and even sexual orientation may shift rapidly (Westen et al., 2011; Skodol, 2005). They may also occasionally have a sense of dissociation, or detachment, from their own thoughts or bodies (Zanarini et al., 2014). Indeed, at times they may have no sense of themselves at all, leading to the feelings of emptiness described earlier.

According to surveys, 5.9 percent of the adult population display borderline personality disorder (Zanarini et al., 2014; Sansone & Sansone, 2011). Close to 75 percent of the patients who receive the diagnosis are women (Gunderson, 2011). The course of the disorder varies from person to person. In the most common pattern, the person’s instability and risk of suicide peak during young adulthood and then gradually wane with advancing age (APA, 2013; Hurt & Oltmanns, 2002). Given the chaotic and unstable relationships characteristic of borderline personality disorder, it is not surprising that the disorder tends to interfere with job performance even more than most other personality disorders do (Hengartner et al., 2014).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Letting It Out

Expression of Anger Only 23 percent of adults report openly expressing their anger (Kanner, 2005, 1995). Around 39 percent say that they hide or contain their anger, and 23 percent walk away to try to collect themselves.

The Myth of Venting Contrary to the notion that “letting off steam” reduces anger, angry participants in one study acted much more aggressively after hitting a punching bag than did angry participants who first sat quietly for a while (Bushman et al., 1999).

How Do Theorists Explain Borderline Personality Disorder?Because a fear of abandonment tortures so many people with borderline personality disorder, psychodynamic theorists have looked once again to early parental relationships to explain the disorder (Gabbard, 2010). Object relations theorists, for example, propose that an early lack of acceptance by parents may lead to a loss of self-

Research has found that this is consistent with the early childhoods of people with borderline personality disorder. In many cases, when they were children, their parents neglected or rejected them, verbally abused them, or otherwise behaved inappropriately (Martín-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Road Ragers Part 1

|

15% |

Percentage of drivers who yell out obscenities when upset by other motorists |

|

14% |

Motorists who have shouted at or had a honking match with another driver in the past year |

|

7% |

Motorists who “give the finger” when upset by other drivers |

|

7% |

Drivers who shake their fists when upset by other drivers |

|

2% |

Motorists who have had a fist fight with another driver |

|

(Information from: OFWW, 2004; Kanner, 2005, 1995; Herman, 1999) |

|

Borderline personality disorder also has been linked to certain biological abnormalities, such as an overly reactive amygdala, the brain structure that is closely tied to fear and other negative emotions, and an underactive prefrontal cortex, the brain region linked to planning, self-

538

A number of theorists currently use a biosocial theory to explain borderline personality disorder (Neacsiu & Linehan, 2014; Rizvi et al., 2011). According to this view, the disorder results from a combination of internal forces (for example, difficulty identifying and controlling one’s emotions, social skill deficits, abnormal neurotransmitter reactions) and external forces (for example, an environment in which a child’s emotions are punished, ignored, trivialized, or disregarded). Parents may, for instance, misinterpret their child’s intense emotions as exaggerations or attempts at manipulation rather than as serious expressions of unsettled internal states. According to the biosocial theory, if children have intrinsic difficulty identifying and controlling their emotions and if their parents teach them to ignore their intense feelings, they may never learn how properly to recognize and control their emotional arousal, how to tolerate emotional distress, or when to trust their emotional responses (Herpertz & Bertsch, 2014; Lazarus et al., 2014; Gratz & Tull, 2011). Such children will be at risk for the development of borderline personality disorder. This theory has received some, but not consistent, research support (Gill & Warburton, 2014).

Note that the biosocial theory is similar to one of the leading explanations for eating disorders. As you saw in Chapter 11, theorist Hilde Bruch proposed that children whose parents do not respond accurately to the children’s internal cues may never learn to identify cues of hunger, thus increasing their risk of developing an eating disorder (see pages 359–

Finally, some sociocultural theorists suggest that cases of borderline personality disorder are particularly likely to emerge in cultures that change rapidly. As a culture loses its stability, they argue, it inevitably leaves many of its members with problems of identity, a sense of emptiness, high anxiety, and fears of abandonment. Family units may come apart, leaving people with little sense of belonging. Changes of this kind in society today may explain growing reports of the disorder (Millon, 2011; Paris, 2010, 1991).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Road Ragers Part 2

|

67% |

Percentage of young adult drivers who consider themselves aggressive drivers |

|

30% |

Percentage of elderly drivers who consider themselves aggressive drivers |

|

59% |

Percentage of drivers with children who say they are likely to respond aggressively to a traffic altercation |

|

45% |

Percentage of drivers without children who say they are likely to respond aggressively to a traffic altercation |

|

66% |

Percentage of all annual traffic fatalities caused by aggressive driving |

|

(Information from: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2010) |

|

539

Treatments for Borderline Personality DisorderIt appears that psychotherapy can eventually lead to some degree of improvement for people with borderline personality disorder (Omar et al., 2014; Neville, 2014). It is, however, extraordinarily difficult for a therapist to strike a balance between empathizing with the borderline client’s dependency and anger and challenging his or her way of thinking (Goodman, Edwards, & Chung, 2014; Gabbard, 2010). Given the emotionally draining demands of clients with borderline personality disorder, some therapists refuse to treat such people. The wildly fluctuating interpersonal attitudes of clients with the disorder can also make it difficult for therapists to establish collaborative working relationships with them (Colli et al., 2014; Goodman et al., 2014). Moreover, clients with borderline personality disorder may violate the boundaries of the client–

Traditional psychoanalysis has not been effective with people with borderline personality disorder (Doering et al., 2010). The clients often experience the psychoanalytic therapist’s reserved style and encouragement of free association as suggesting disinterest and abandonment. The clients may also have difficulty tolerating interpretations made by psychoanalytic therapists and see them as attacks.

Contemporary psychodynamic approaches, such as relational psychoanalytic therapy (see page 67), in which therapists take a more supportive and egalitarian posture, have been more effective than traditional psychoanalytic approaches. In approaches of this kind, therapists work to provide an empathic setting within which borderline clients can explore their unconscious conflicts and pay particular attention to their central relationship disturbance, poor sense of self, and pervasive loneliness and emptiness (Goodman et al., 2014; Gabbard, 2010, 2001; Muran et al., 2010). Research has found that contemporary psychodynamic treatments sometimes help reduce suicide attempts, self-

Over the past two decades, an integrative treatment for borderline personality disorder, called dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), has been receiving considerable research support and is now considered the treatment of choice in many clinical circles (Neacsiu & Linehan, 2014; Linehan et al., 2006, 2002, 2001). DBT, developed by psychologist Marsha Linehan, grows largely from the cognitive-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“Anger is a brief lunacy.”

Horace, Roman poet

DBT also borrows heavily from the humanistic and contemporary psychodynamic approaches, placing the client–

540

MediaSpeak

The Patient as Therapist

By Benedict Carey, The New York Times, June 23, 2011

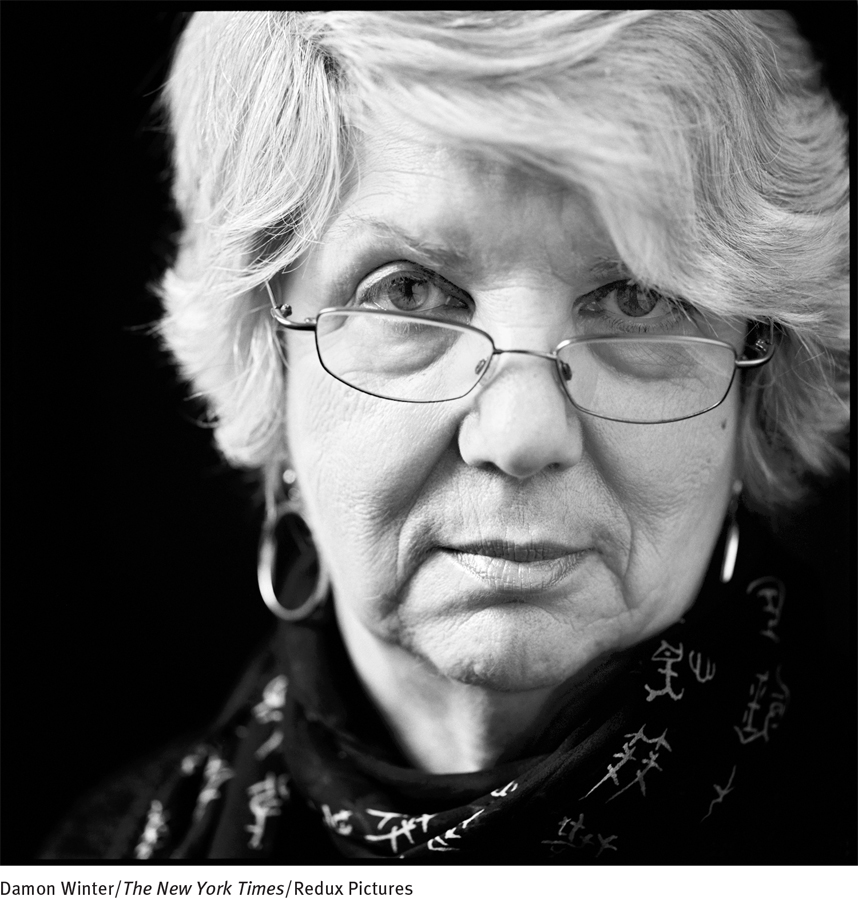

Marsha M. Linehan, 68 … told her story in public for the first time last week….

Dr. Linehan … was driven by a mission to rescue people who are chronically suicidal, often as a result of borderline personality disorder, an enigmatic condition characterized in part by self-

She learned the central tragedy of severe mental illness the hard way, banging her head against the wall of a locked room.

Marsha Linehan arrived at the Institute of Living on March 9, 1961, at age 17, and quickly became the sole occupant of the seclusion room on the unit known as Thompson Two, for the most severely ill patients. The staff saw no alternative: The girl attacked herself habitually, burning her wrists with cigarettes, slashing her arms, her legs, her midsection, using any sharp object she could get her hands on.

The seclusion room … had no such weapon. Yet her urge to die only deepened….

“I was in hell,” she said. “And I made a vow: when I get out, I’m going to come back and get others out of here.” …

It took years of study in psychology—

Dr. Linehan was closing in on two seemingly opposed principles that could form the basis of a treatment: acceptance of life as it is, not as it is supposed to be; and the need to change, despite that reality and because of it….

She chose to treat people with a diagnosis that she would have given her young self: borderline personality disorder….

Yet even as she climbed the academic ladder, moving from the Catholic University of America to the University of Washington in 1977, she understood from her own experience that acceptance and change were hardly enough…. She relied on therapists herself, off and on over the years, for support and guidance….

Dr. Linehan’s own emerging approach to treatment—

In studies in the 1980s and ‘90s, researchers at the University of Washington and elsewhere tracked the progress of hundreds of borderline patients at high risk of suicide who attended weekly dialectical therapy sessions. Compared with similar patients who got other experts’ treatments, those who learned Dr. Linehan’s approach made far fewer suicide attempts, landed in the hospital less often and were much more likely to stay in treatment. D.B.T. is now widely used for a variety of clients, including juvenile offenders….

What might be the positives and negatives—

Most remarkably, perhaps, Dr. Linehan has reached a place where she can stand up and tell her story, come what will. “I’m a very happy person now.” … “I still have ups and downs, of course, but I think no more than anyone else.”

June 23, 2011, “Lives Restored: Expert on Mental Illness Reveals Her Own Fight” by Benedict Carey, From The New York Times, 6/23/2011, © 2011 The New York Times. All rights reserved. Used by permission and protected by the copyright laws of the United States. The printing, copying, redistribution, or retransmission of this content without express written permission is prohibited.

541

DBT is often supplemented by the clients’ participation in social skill-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Dealing with Anger

Women are 2.5 times more likely than men to turn to food as a way to calm down when angry.

According to surveys, men are 3 times more likely than women to use sex as a way to calm down when angry.

Women are 56 percent more likely than men to “yell a lot” when angry.

Men are 35 percent more likely than women to “seethe quietly” when angry.

(Zoellner, 2000)

DBT has received more research support than any other treatment for borderline personality disorder (Neacsiu & Linehan, 2014; Roepke et al., 2011). Many clients who receive DBT become more able to tolerate stress; develop new, more appropriate, social skills; respond more effectively to life situations; and develop a more stable identity. They also have significantly fewer suicidal behaviors and require fewer hospitalizations than those who receive other forms of treatment (Klein & Miller, 2011). In addition, they are more likely to remain in treatment and to report less anger, more social gratification, improved work performance, and reductions in substance abuse (Rizvi et al., 2011).

Antidepressant, antibipolar, antianxiety, and antipsychotic drugs have helped calm the emotional and aggressive storms of some people with borderline personality disorder (Black et al., 2014; Knappich et al., 2014; Martinho et al., 2014). However, given the numerous suicide attempts by people with this disorder, the use of drugs on an outpatient basis is controversial (Gunderson, 2011). Additionally, clients with the disorder have been known to adjust or discontinue their medication dosages without consulting their clinicians. Many professionals believe that psychotropic drug treatment for borderline personality disorder should be used largely as an adjunct to psychotherapy approaches, and indeed many clients seem to benefit from a combination of psychotherapy and drug therapy (Omar et al., 2014; Soloff, 2005).

Histrionic Personality Disorder

People with histrionic personality disorder, once called hysterical personality disorder, are extremely emotional—

histrionic personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by a pattern of excessive emotionality and attention seeking. Once called hysterical personality disorder.

histrionic personality disorder A personality disorder characterized by a pattern of excessive emotionality and attention seeking. Once called hysterical personality disorder.

BETWEEN THE LINES

What Is the Difference Between an Egoist and an Egotist?

An egoist is a person concerned primarily with his or her own interests. An egotist has an inflated sense of self-

Unhappy over her impending divorce, Lucinda decided to seek counseling. She arrived at her first session wearing a very provocative outfit, including a revealing blouse and extremely short skirt. Her hair had been labored over, and she had on an excessive amount of makeup—

When asked to discuss her separation, Lucinda first insisted that the therapist call her Cindy, saying, “All my close friends call me that, and I like to think that you and I will become very good friends here.” She said that her husband, Morgan had suddenly abandoned her—

Lucinda said that when Morgan first told her that he wanted a divorce, she did not know whether she could go on. The pain was palpable. After all, they had been so “incredibly and irrevocably” close, and he had been so very devoted to her. He had always taken such wonderful care of her, always placed her first. She was his everything.

542

She said that initially she even had thoughts of doing away with herself. But, of course, she knew that she had to pull herself together. So many people needed her to be strong. So many people relied on her, particularly her “dear friends” and her sister. She had deep and special relationships with them all, relationships that had to be nurtured. Right now, her inner circle was rallying around her—

The therapy discussion returned to the divorce itself. She told the therapist that without Morgan she would now need a man to take care of her—

When the therapist attempted to steer the conversation back to Morgan, Lucinda became petulant and asked, “Do we really need to talk about that abusive lout?” Pressed on the word “abusive,” Lucinda replied that she was referring to “mental cruelty.” Morgan had, after all, called her inadequate and worthless throughout their marriage and told her that everything good in her life had been due to him. When her therapist pointed out that this seemed to contradict the rosy picture she had just painted of Morgan and their married life, she quickly changed the subject, stating that she thought she was running out of time to have a child. She said her life would be “absolutely ruined” if she did not have a child by the age of 32.

As the session came to a close, Lucinda’s therapist suggested that it might be useful for him to meet with Morgan. She loved the idea, saying, “Then he’ll know the competition he has!”

When he met with Morgan a few days later, the therapist heard a very different story than the one presented by Lucinda. Morgan said, “I really loved Cindy—

The real surprise for the therapist came when Morgan described Lucinda’s social life. He said that she had virtually no close friends. The “dear and special” friendships she had spoken of during her therapy session were really just casual relationships—

People with histrionic personality disorder are always “on stage,” using theatrical gestures and mannerisms and grandiose language to describe ordinary everyday events. Like chameleons, they keep changing themselves to attract and impress an audience, and in their pursuit they change not only their surface characteristics—

543

Approval and praise are their lifeblood; they must have others present to witness their exaggerated emotional states. Vain, self-

People with histrionic personality disorder may draw attention to themselves by exaggerating their physical illnesses or fatigues. They may also behave very provocatively and try to achieve their goals through sexual seduction. Most obsess over how they look and how others will perceive them, often wearing bright, eye-

This disorder was once believed to be more common in women than in men, and clinicians long described the “hysterical wife” (Anderson et al., 2001). Research, however, has revealed gender bias in past diagnoses (APA, 2013; Fowler et al., 2007; Ford & Widiger, 1989). When evaluating case studies of people with a mixture of histrionic and antisocial traits, clinicians in several studies gave a diagnosis of histrionic personality disorder to women more than men. Surveys suggest that 1.8 percent of adults have this personality disorder, with males and females equally affected (APA, 2013; Sansone & Sansone, 2011).

How Do Theorists Explain Histrionic Personality Disorder?The psychodynamic perspective was originally developed to help explain cases of hysteria (see Chapter 10), so it is no surprise that psychodynamic theorists continue to have a strong interest in histrionic personality disorder. Most psychodynamic theorists believe that as children, people with this disorder had cold and controlling parents who left them feeling unloved and afraid of abandonment (Horowitz & Lerner, 2010; Bender et al., 2001). To defend against deep-

Cognitive explanations look instead at the lack of substance and extreme suggestibility that people with histrionic personality disorder have. Cognitive theorists see these people as becoming less and less interested in knowing about the world at large because they are so self-

Sociocultural, particularly multicultural, theorists believe that histrionic personality disorder is produced in part by cultural norms and expectations. Until recently, our society encouraged girls to hold on to childhood and dependency as they grew up. The vain, dramatic, and selfish behavior of the histrionic personality may actually be an exaggeration of femininity as our culture once defined it (Fowler et al., 2007). Similarly, some clinical observers claim that histrionic personality disorder is diagnosed less often in Asian and other cultures that discourage overt sexualization and more often in Hispanic American and Latin American cultures that are more tolerant of overt sexualization (Patrick, 2007; Trull & Widiger, 2003). Researchers have not, however, investigated this claim systematically.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“The hysterical find too much significance in things. The depressed find too little.”

Mason Cooley, American aphorist

544

Treatments for Histrionic Personality DisorderPeople with histrionic personality disorder are more likely than those with most other personality disorders to seek out treatment on their own (Tyrer et al., 2003). Working with them can be very difficult, however, because of the demands, tantrums, and seductiveness they are likely to deploy. Another problem is that these clients may pretend to have important insights or to change during treatment merely to please the therapist. To head off such problems, therapists must remain objective and maintain strict professional boundaries (Colli et al., 2014; Blagov et al., 2007).

Cognitive therapists have tried to help people with this disorder to change their belief that they are helpless and also to develop better, more deliberate ways of thinking and solving problems (Beck & Weishaar, 2014; Weishaar & Beck, 2006; Beck et al., 2004). Psychodynamic therapy and various group therapy formats have also been used (Horowitz & Lerner, 2010). In all these approaches, therapists ultimately aim to help the clients recognize their excessive dependency, find inner satisfaction, and become more self-

Narcissistic Personality Disorder

People with narcissistic personality disorder are generally grandiose, need much admiration, and feel no empathy with others (APA, 2013). Convinced of their own great success, power, or beauty, they expect constant attention and admiration from those around them. Frederick, the man whom we met at the beginning of this chapter, was one such person. So is Steven, a 30-

narcissistic personality disorder A personality disorder marked by a broad pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy.

narcissistic personality disorder A personality disorder marked by a broad pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and lack of empathy.

Steven came to the attention of a therapist when his wife insisted that they seek marital counseling. According to her, Steve was “selfish, ungiving and preoccupied with his work.” Everything at home had to “revolve about him, his comfort, moods and desires, no one else’s.” She claimed that he contributed nothing to the marriage, except a rather meager income. He shirked all “normal” responsibilities and kept “throwing chores in her lap,” and she was “getting fed up with being the chief cook and bottlewasher, tired of being his mother and sleep-

On the positive side, Steven’s wife felt that he was basically a “gentle and good-

Steve presented a picture of an affable, self-

His relationships with his present co-

(Millon, 1969, pp. 261–

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“To love oneself is the beginning of a lifelong romance.”

Oscar Wilde, An Ideal Husband (1895)

545

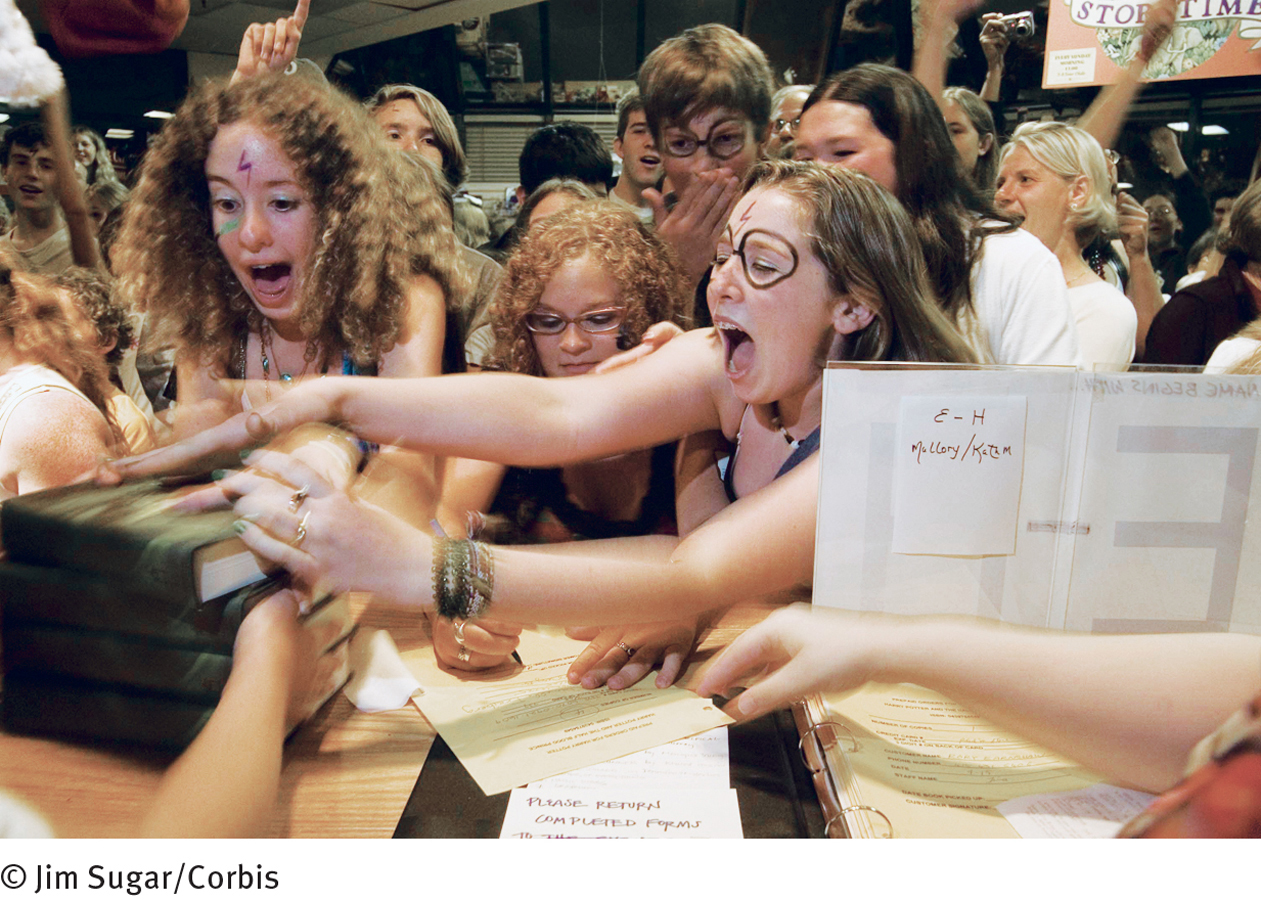

In the Greek myth, Narcissus died enraptured by the beauty of his own reflection in a pool, pining away with longing to possess his own image. His name has come to be synonymous with extreme self-

Why do people often admire arrogant deceivers—

Like Steven, people with narcissistic personality disorder are seldom interested in the feelings of others. They may not even be able to empathize with such feelings (Baskin-

As many as 6.2 percent of adults display narcissistic personality disorder, up to 75 percent of them men (APA, 2013; Sansone & Sansone, 2011). Narcissistic-

How Do Theorists Explain Narcissistic Personality Disorder?Psychodynamic theorists more than others have theorized about narcissistic personality disorder, and they again propose that the problem begins with cold, rejecting parents. They argue that some people with this background spend their lives defending against feeling unsatisfied, rejected, unworthy, ashamed, and wary of the world (Roepke & Vater, 2014;Ronningstam, 2011;Bornstein, 2005). They do so by repeatedly telling themselves that they are actually perfect and desirable, and also by seeking admiration from others. Object relations theorists—

A number of cognitive-

546

MindTech

Selfies: Narcissistic or Not?

In the art world, people have been drawing self-

As the selfie phenomenon has grown, opinions about selfies have intensified. It seems like people either love them or hate them. This is true in the field of psychology as well. Some psychologists view taking selfies as a form of narcissistic behavior, while others view them more positively.

First, the negative perspective. Many sociocultural theorists see a link between narcissistic personality disorder and “eras of narcissism” in society (Paris, 2014). They suggest that social values in society break down periodically, producing generations of self-

This lack of support for the narcissism viewpoint does not mean that selfies, especially repeated selfie behaviors, are completely harmless. Sherry Turkle (2013), an influential technology psychologist, believes that the near-

Psychologists also observe that posting too many “selfies” may alienate those who view the poster’s social media profile (Miller, 2013). Studies have found, for example, that people often take a negative view of friends and family members who excessively post photos to their Facebook sites (Houghton, 2013).

What other trends in behavior—

On the positive side, a number of psychologists believe that the criticisms and concerns about the selfie movement have been overstated. Media psychologist Pamela Rutledge (2013) views selfies as an inevitable by-

In short, like other technological trends you’ve read about, the selfie phenomenon has received mixed grades from psychology researchers and practitioners so far. ![]()

547

Many sociocultural theorists see a link between narcissistic personality disorder and “eras of narcissism” in society (Paris, 2014; Campbell & Miller, 2011). They suggest that family values and social ideals in certain societies periodically break down, producing generations of young people who are self-

What specific features of Western society may be contributing to today’s apparent rise in narcissistic behavior?

Treatments for Narcissistic Personality DisorderNarcissistic personality disorder is one of the most difficult personality patterns to treat because the clients are unable to acknowledge weaknesses, to appreciate the effect of their behavior on others, or to incorporate feedback from others (Campbell & Miller, 2011). The clients who consult therapists usually do so because of a related disorder such as depression (APA, 2013; Piper & Joyce, 2001). Once in treatment, the clients may try to manipulate the therapist into supporting their sense of superiority. Some also seem to project their grandiose attitudes onto their therapists and develop a love-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Portrait in Vanity

King Frederick V, ruler of Denmark from 1746 to 1766, had his portrait painted at least 70 times by the same artist, Carl Pilo.

(Shaw, 2004)

Psychodynamic therapists seek to help people with this disorder recognize and work through their basic insecurities and defenses (Diamond & Meehan, 2013; Messer & Abbass, 2010). Cognitive therapists, focusing on the self-