17.2 Childhood Anxiety Disorders

Anxiety is, to a degree, a normal part of childhood. Since children have had fewer experiences than adults, their world is often new and scary. They may be frightened by common events, such as the beginning of school, or by special upsets, such as moving to a new house or becoming seriously ill. In addition, each generation of children is confronted by new sources of anxiety. Today’s children, for example, are repeatedly warned, both at home and at school, about the dangers of Internet browsing and networking, child abduction, drugs, and terrorism. They are bombarded by violent images on the Web, on television, or in movies. Even fairy tales and nursery rhymes contain frightening images that upset many children.

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“It is an illusion that youth is happy, an illusion of those who have lost it.”

W. Somerset Maugham, Of Human Bondage, 1915

Children may also be strongly affected by parental problems or inadequacies. If, for example, parents typically react to events with high levels of anxiety or if they overprotect their children, the children may be more likely to respond to the world with anxiety (Becker et al., 2010; Levavi et al., 2010). Similarly, if parents repeatedly reject, disappoint, or avoid their children, the world may seem an unpleasant and anxious place for them. And if parents are divorced, become seriously ill, or must be separated from their children for a long period, childhood anxiety may result. Beyond such environmental problems, there is genetic evidence that some children are prone to an anxious temperament (Rogers et al., 2013).

566

InfoCentral

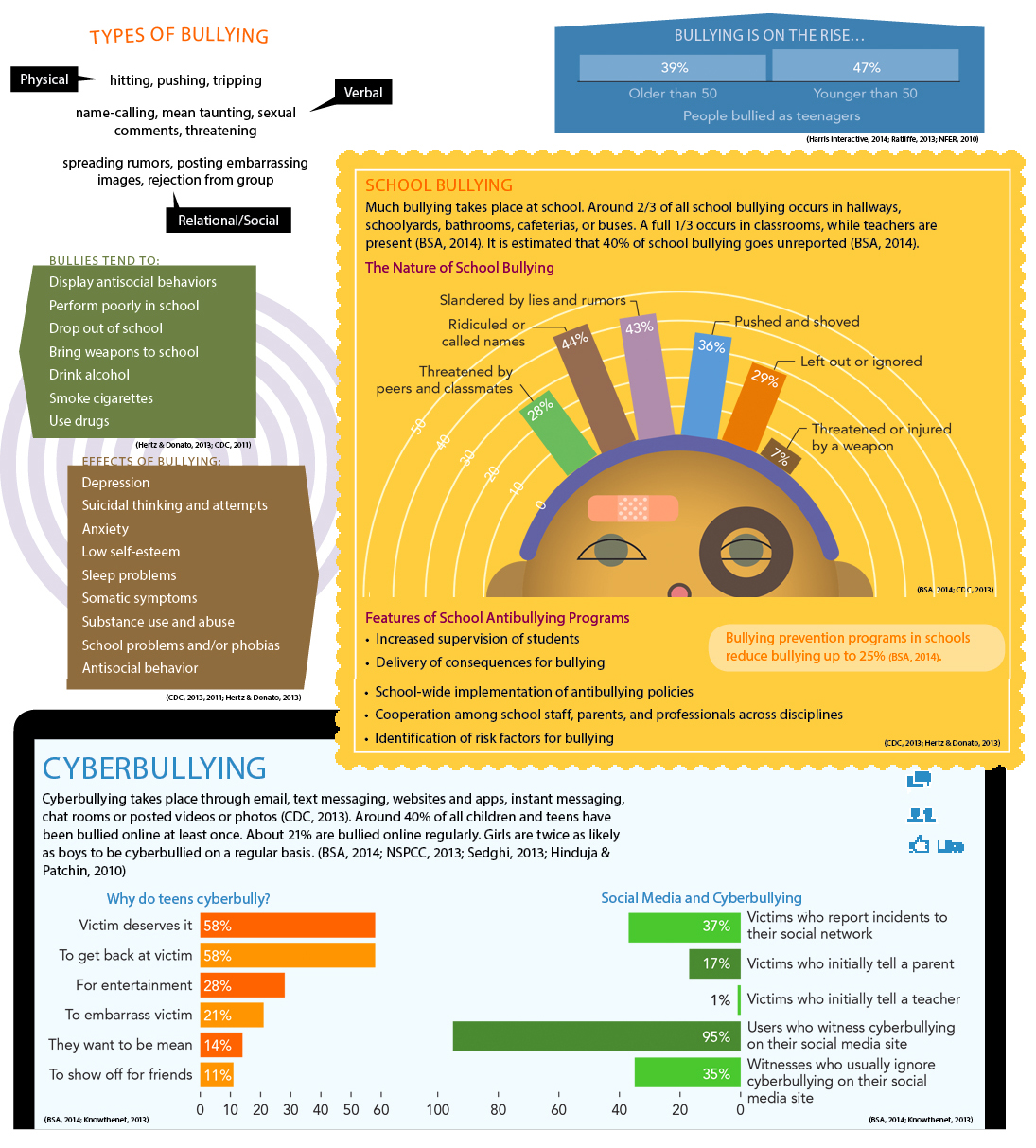

CHILD AND ADOLESCENT BULLYING

Bullying is the repeated inf liction of force, threats, or coercion in order to intimidate, hurt, or dominate another—

567

For some children, such anxieties become long-

More often, however, the anxiety disorders of childhood take on a somewhat different character from that of adult anxiety disorders. Consider generalized anxiety disorder, marked by constant worrying, and social anxiety disorder, marked by fears of embarrassing oneself in front of others (APA, 2013). In order to have such disorders, people must be able to anticipate future negative events (losing one’s job, having a car accident, fainting in front of others), to take on the perspective of other people, and/or to recognize that the thoughts and beliefs of others differ from their own. These cognitive skills are simply beyond the capacity of very young children, and so the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder do not usually appear in earnest until children are 7 years old or older. In short, odd as it may sound, some patterns of anxiety cannot fully unfold until children are afforded the “benefits” of cognitive, physical, and emotional growth (Davis & Ollendick, 2011; Weems & Varela, 2011).

What, then, do the anxiety disorders of young children look like? Typically they are dominated by behavioral and somatic symptoms rather than cognitive ones—

Separation Anxiety Disorder

Separation anxiety disorder, one of the most common anxiety disorders among children, follows this profile (APA, 2013). The disorder is common (but not unique) to childhood, begins as early as the preschool years, and at least 4 percent of all children experience it (APA, 2013; Mash & Wolfe, 2012). Sufferers feel extreme anxiety, often panic, whenever they are separated from home or a parent. Jonah’s symptoms began when he was a preschooler and continued into kindergarten.

separation anxiety disorder A disorder marked by excessive anxiety, even panic, whenever the person is separated from home, a parent, or another attachment figure.

separation anxiety disorder A disorder marked by excessive anxiety, even panic, whenever the person is separated from home, a parent, or another attachment figure.

Jonah, age 4, began crying as soon as his parents tried to place him in their car for the 30-

Jonah screamed that he would not get in the car. He pleaded to stay home, saying, “I don’t like being with Granny. I hate Tuesdays!” When Mia insisted he stop saying such mean things, Jonah further yelled out, “I only want to be here with you! If you make me go, I’ll never see you again!"

568

Jonah’s father Brandon told him he was being silly, but Jonah cried out, “What if you like it better without me? What if Granny decides to keep me and won’t let you have me back? Or what if you die!” Exasperated, Brandon picked Jonah up and carried him to the car. Jonah cried all the way to his grandparent’s house. At the door, Jonah hugged his mother as though he would never let go. After Mia finally broke off the hug, Jonah tried to make a break for it and ran back toward the car.

Intercepted by Brandon, Jonah finally went inside the house and sat down. He was no longer crying out, but he continued to whimper and to beg for a reprieve. Eventually, Mia and Brandon left. Two hours later, they received a phone call from Mia’s flustered mother. An inconsolable Jonah had been crying nonstop, at the top of his lungs, since his parents had left. Reluctantly, Mia agreed to pick Jonah up, cancelling her and Brandon’s weekend getaway. There was no way that they would have had much fun anyway, knowing that Jonah was so upset.

That night, Jonah refused to sleep in his own room, insisting on sleeping between his parents. This was something they had tolerated occasionally in the past, but, beginning that night, it became a regular sleeping arrangement. During the next several months, all attempts to reschedule the weekend trip to his grandparents had to be cancelled, as Jonah became hysterical every time his parents tried to get him to leave the house. He also became more agitated during his grandmother’s Tuesday visits, constantly yelling, “I want Mommy!”

Five months later, Jonah began kindergarten. That first day of school lasted all of two hours. A school administrator called, asking Mia to come get Jonah. Mia was hardly surprised. Jonah had cried, screamed, and even kicked the whole ride to school, and his distress only escalated as she drove off. The school administrator was sympathetic to Jonah’s anxiety and to Mia’s plight, but, as he explained, Jonah’s nonstop crying was affecting all the other children and making it impossible for the teacher to get them comfortable and involved in their class activities. “Perhaps tomorrow Jonah will have a better day,” he said. But the next day, Jonah’s reaction was the same. And the next day. And the next day.

Children like Jonah have enormous trouble traveling away from their family, and they often refuse to visit friends’ houses, go on errands, or attend camp or school (see Table 17-1). Many cannot even stay alone in a room and cling to their parent around the house. Some also have temper tantrums, cry, or plead to keep their parents from leaving them. The children may fear that they will get lost when separated from their parents or that the parents will meet with an accident or illness. As long as the children are near their parents and not threatened by separation, they may function quite normally. At the first hint of separation, however, the dramatic pattern of symptoms may be set in motion.

|

Separation Anxiety Disorder |

|

|---|---|

|

1. |

Individual displays fear or anxiety concerning separation from attachment figures, anxiety that is unreasonable or excessive for his or her age group. |

|

2. |

Individual’s excessive anxiety features three or more of the following symptoms: • Repeated separation- |

|

3. |

Individual’s symptoms last 4 or more weeks for children and at least 6 months for adults. |

|

4. |

Significant distress or impairment. |

|

(Information from: APA, 2013) |

|

Separation anxiety disorder may further take the form of a school phobia, or school refusal, a common problem in which children fear going to school and often stay home for a long period (APA, 2013). Many cases of school phobia, however, have causes other than separation fears, such as social or academic fears, depression, and fears of specific objects or persons at school.

Treatments for Childhood Anxiety Disorders

Despite the high prevalence of childhood and adolescent anxiety disorders, around two-

569

BETWEEN THE LINES

Children in Need

Almost half of students identified with significant emotional disturbances drop out of high school.

Currently there is 1 school counselor for every 476 students. The recommended ratio is 1 per 250 students.

(ASCA, 2010; Planty et al., 2008; Gruttadaro, 2005)

Clinicians have also used drug therapy in a number of cases of childhood anxiety disorders, often in combination with psychotherapy (Mohat et al., 2014; Bloch & McGuire, 2011). Not only do they prescribe antianxiety drugs, but antidepressant and antipsychotic drugs as well (Comer et al., 2011, 2010). Drug therapy for childhood anxiety appears to be helpful, but it has begun only recently to receive much research attention.

Because children typically have difficulty recognizing and understanding their feelings and motives, many therapists, particularly psychodynamic therapists, use play therapy as part of treatment (Landreth, 2012). In this approach, the children play with toys, draw, and make up stories; in doing so they reveal the conflicts in their lives and their related feelings. The therapists then introduce more play and fantasy to help the children work through their conflicts and change their emotions and behavior. In addition, because children are often excellent hypnotic subjects, some therapists use hypnotherapy to help them overcome intense fears.

play therapy An approach to treating childhood disorders that helps children express their conflicts and feelings indirectly by drawing, playing with toys, and making up stories.

play therapy An approach to treating childhood disorders that helps children express their conflicts and feelings indirectly by drawing, playing with toys, and making up stories.