1.4 Current Trends

It would hardly be accurate to say that we now live in a period of great enlightenment about or dependable treatment of mental disorders. In fact, surveys have found that 43 percent of respondents believe that people bring mental disorders on themselves, and 35 percent consider such disorders to be caused by sinful behavior (Stuber et al., 2014; Stanford, 2007; NMHA, 1999). Nevertheless, there have been major changes over the past 50 years in the ways clinicians understand and treat abnormal functioning. There are more theories and types of treatment, more research studies, more information, and—

18

How Are People with Severe Disturbances Cared For?

In the 1950s, researchers discovered a number of new psychotropic medications—drugs that primarily affect the brain and reduce many symptoms of mental dysfunctioning. They included the first antipsychotic drugs, which correct extremely confused and distorted thinking; antidepressant drugs, which lift the mood of depressed people; and antianxiety drugs, which reduce tension and worry.

psychotropic medications Drugs that mainly affect the brain and reduce many symptoms of mental dysfunctioning.

psychotropic medications Drugs that mainly affect the brain and reduce many symptoms of mental dysfunctioning.

When given these drugs, many patients who had spent years in mental hospitals began to show signs of improvement. Hospital administrators, encouraged by these results and pressured by a growing public outcry over the terrible conditions in public mental hospitals, began to discharge patients almost immediately.

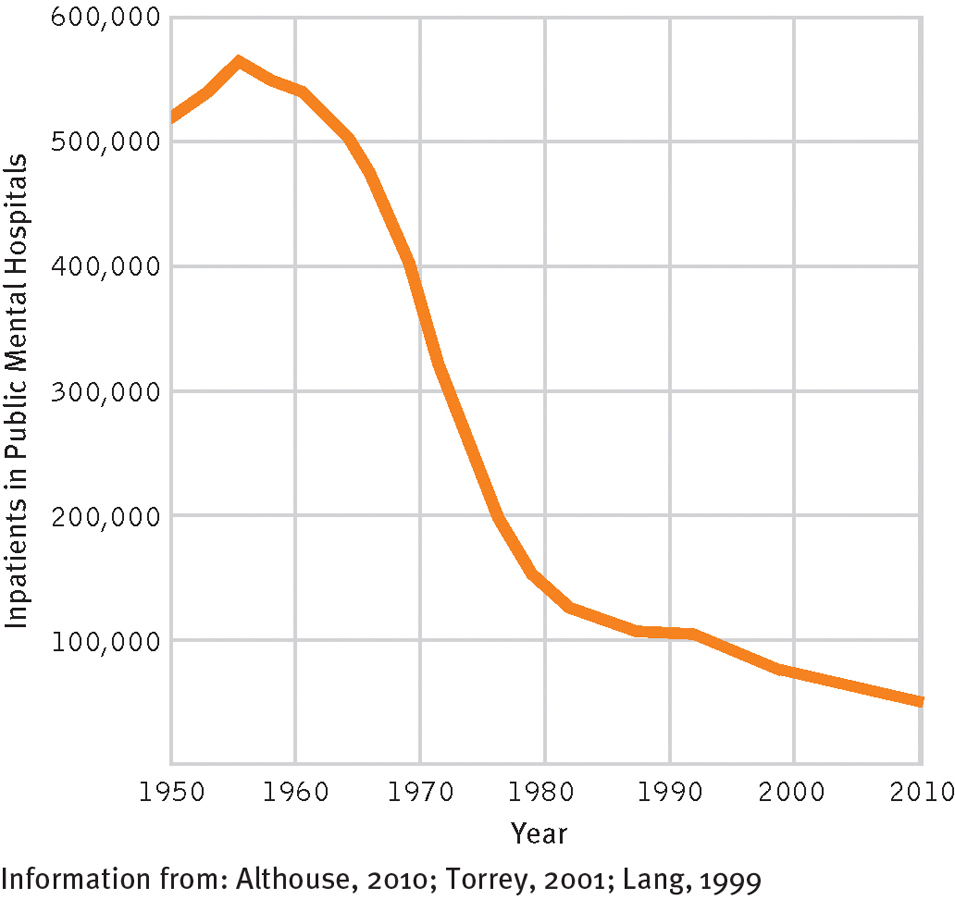

Since the discovery of these medications, mental health professionals in most of the developed nations of the world have followed a policy of deinstitutionalization, releasing hundreds of thousands of patients from public mental hospitals. On any given day in 1955, close to 600,000 people were confined in public mental institutions across the United States (see Figure 1-1). Today the daily patient population in the same kinds of hospitals is less than 40,000 (Althouse, 2010).

deinstitutionalization The practice, begun in the 1960s, of releasing hundreds of thousands of patients from public mental hospitals.

deinstitutionalization The practice, begun in the 1960s, of releasing hundreds of thousands of patients from public mental hospitals.

The impact of deinstitutionalization

The number of patients (fewer than 40,000) now hospitalized in public mental hospitals in the United States is a small fraction of the number hospitalized in 1955.

In short, outpatient care has now become the primary mode of treatment for people with severe psychological disturbances as well as for those with more moderate problems. When severely disturbed people do need institutionalization these days, they are usually hospitalized for a short period of time. Ideally, they are then provided with outpatient psychotherapy and medication in community programs and residences (Goldman & Tansella, 2013; McEvoy & Richards, 2007).

Chapters 3 and 15 will look more closely at this recent emphasis on community care for people with severe psychological disturbances—

How Are People with Less Severe Disturbances Treated?

The treatment picture for people with moderate psychological disturbances has been more positive than that for people with severe disorders. Since the 1950s, outpatient care has continued to be the preferred mode of treatment for them, and the number and types of facilities that offer such care have expanded to meet the need.

Before the 1950s, almost all outpatient care took the form of private psychotherapy, an arrangement by which an individual directly pays a psychotherapist for counseling services. This tended to be an expensive form of treatment, available only to the wealthy. Since the 1950s, however, most health insurance plans have expanded coverage to include private psychotherapy, so that it is now also widely available to people with more modest incomes. In addition, outpatient therapy is now offered in a number of less expensive settings, such as community mental health centers, crisis intervention centers, family service centers, and other social service agencies. The new settings have spurred a dramatic increase in the number of people seeking outpatient care for psychological problems. Surveys suggest that nearly one of every six adults in the United States receives treatment for psychological disorders in the course of a year (NIMH, 2010). The majority of clients are seen for fewer than five sessions during the year.

private psychotherapy An arrangement in which a person directly pays a therapist for counseling services.

private psychotherapy An arrangement in which a person directly pays a therapist for counseling services.

19

Outpatient treatments are also becoming available for more and more kinds of problems. When Freud and his colleagues first began to practice, most of their patients suffered from anxiety or depression. Almost half of today’s clients suffer from those same problems, but people with other kinds of disorders are also receiving therapy. In addition, at least 20 percent of clients enter therapy because of milder problems in living—

Yet another change in outpatient care since the 1950s has been the development of programs devoted exclusively to one kind of psychological problem. We now have, for example, suicide prevention centers, substance abuse programs, eating disorder programs, phobia clinics, and sexual dysfunction programs. Clinicians in these programs have the kind of expertise that can be acquired only by concentration in a single area.

A Growing Emphasis on Preventing Disorders and Promoting Mental Health

Although the community mental health approach has often failed to address the needs of people with severe disorders, it has given rise to an important principle of mental health care—

prevention Interventions aimed at deterring mental disorders before they can develop.

prevention Interventions aimed at deterring mental disorders before they can develop.

20

Prevention programs have been further energized in the past few years by the field of psychology’s ever-

positive psychology The study and enhancement of positive feelings, traits, and abilities.

positive psychology The study and enhancement of positive feelings, traits, and abilities.

Why do you think it has taken psychologists so long to start studying positive behaviors?

In the clinical arena, positive psychology suggests that practitioners can help people best by promoting positive development and psychological wellness. While researchers study and learn more about positive psychology in the laboratory, clinicians with this orientation teach people coping skills that may help protect them from stress and adversity and encourage them to become more involved in personally meaningful activities and relationships (Sergeant & Mongrain, 2014; Bolier et al., 2013). In this way, the clinicians are trying to promote mental health and prevent mental disorders.

Multicultural Psychology

We are, without question, a society of multiple cultures, races, and languages. Members of racial and ethnic minority groups in the United States collectively make up 35 percent of the population, a percentage that is expected to grow to more than 50 percent in the coming decades (Santa-

In response to this growing diversity, a new area of study called multicultural psychology has emerged. Multicultural psychologists seek to understand how culture, race, ethnicity, gender, and similar factors affect behavior and thought and how people of different cultures, races, and genders may differ psychologically (Alegría et al., 2013, 2010, 2004). As you will see throughout this book, the field of multicultural psychology has begun to have a powerful effect on our understanding and treatment of abnormal behavior.

multicultural psychology The field that examines the impact of culture, race, ethnicity, and gender on behaviors and thoughts and focuses on how such factors may influence the origin, nature, and treatment of abnormal behavior.

multicultural psychology The field that examines the impact of culture, race, ethnicity, and gender on behaviors and thoughts and focuses on how such factors may influence the origin, nature, and treatment of abnormal behavior.

The Increasing Influence of Insurance Coverage

So many people now seek therapy that private insurance companies have changed their coverage for mental health patients. Today the dominant form of coverage is the managed care program—a program in which the insurance company determines such key issues as which therapists its clients may choose, the cost of sessions, and the number of sessions for which a client may be reimbursed (Domino, 2012; Glasser, 2010).

managed care program Health care coverage in which the insurance company largely controls the nature, scope, and cost of medical or psychological services.

managed care program Health care coverage in which the insurance company largely controls the nature, scope, and cost of medical or psychological services.

At least 75 percent of all privately insured persons in the United States are currently enrolled in managed care programs (Deb et al., 2006; Kiesler, 2000). The coverage for mental health treatment under such programs follows the same basic principles as coverage for medical treatment, including a limited pool of practitioners from which patients can choose, preapproval of treatment by the insurance company, strict standards for judging whether problems and treatments qualify for reimbursement, and ongoing reviews and assessments. In the mental health realm, both therapists and clients typically dislike managed care programs (Lustig et al., 2013; Schneid, 2010). They fear that the programs inevitably shorten therapy (often for the worse), unfairly favor treatments whose results are not always lasting (for example, drug therapy), pose a special hardship for those with severe mental disorders, and result in treatments determined by insurance companies rather than by therapists (Turner, 2013; Glasser, 2010).

21

InfoCentral

HAPPINESS

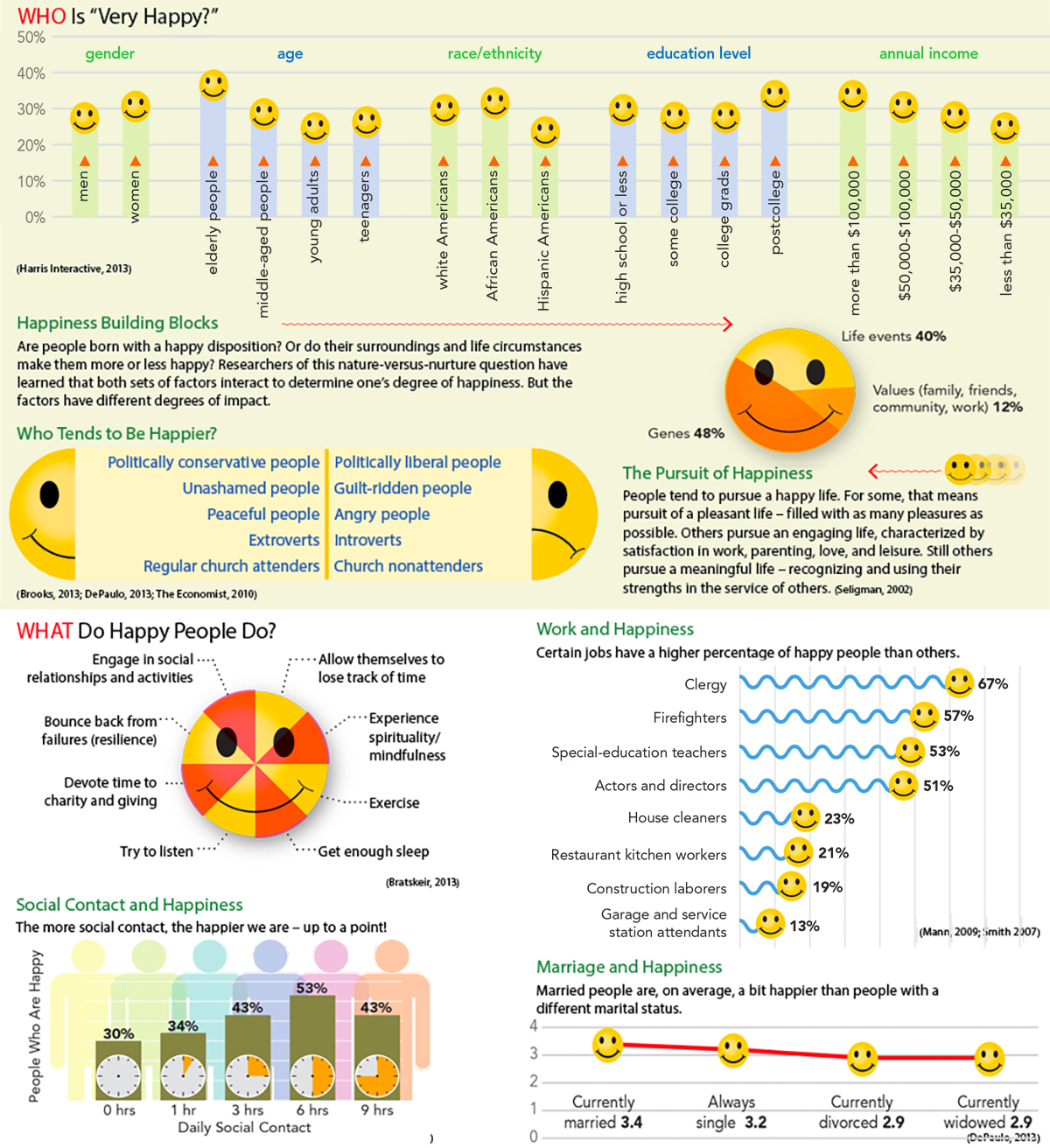

Positive psychology is the study of positive feelings, traits, and abilities. A better understanding of constructive functioning enables clinicians to better promote psychological wellness. Happiness is the positive psychology topic currently receiving the most attention. Many, but far from all, people are happy. In fact, only one-

22

A key problem with insurance coverage—

What Are Today’s Leading Theories and Professions?

BETWEEN THE LINES

Gender Shift

|

28% |

Psychologists in 1978 who were female |

|

52% |

Psychologists today who are female |

|

77% |

Current undergraduate psychology majors who are female |

|

72% |

Current psychology graduate students who are female |

|

(Cherry, 2014; Carey, 2011; Cynkar, 2007; Barber, 1999) |

|

One of the most important developments in the clinical field has been the growth of numerous theoretical perspectives that now coexist in the field. Before the 1950s, the psychoanalytic perspective, with its emphasis on unconscious psychological problems as the cause of abnormal behavior, was dominant. Then the discovery of effective psychotropic drugs inspired new respect for the somatogenic, or biological, view. As you will see in Chapter 3, other influential perspectives that have emerged since the 1950s are the behavioral, cognitive, humanistic-

In addition, a variety of professionals now offer help to people with psychological problems. Before the 1950s, psychotherapy was offered only by psychiatrists, physicians who complete three to four additional years of training after medical school (a residency) in the treatment of abnormal mental functioning. After World War II, however, with millions of soldiers returning home to countries throughout North America and Europe, the demand for mental health services expanded so rapidly that other professional groups had to step in to fill the need.

Among those other groups are clinical psychologists—professionals who earn a doctorate in clinical psychology by completing four to five years of graduate training in abnormal functioning and its treatment and also complete a one-

23

|

|

Degree |

Began to Practice |

Current Number |

Average Annual Salary |

Percent Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Psychiatrists |

MD, DO |

1840s |

50,000 |

$144,020 |

25 |

|

Psychologists |

PhD, PsyD, EdD |

Late 1940s |

174,000 |

$63,000 |

52 |

|

Social workers |

MSW, DSW |

Early 1950s |

607,000 |

$43,040 |

77 |

|

Counselors |

Various |

Early 1950s |

475,000 |

$47,530 |

90 |

|

Information from: Cherry, 2014; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014, 2011, 2002; AMA, 2011; Carey, 2011; Weissman, 2000. |

|||||

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“I would rather have anything wrong with my body than something wrong with my head.”

Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar

A related development in the study and treatment of mental disorders since World War II has been a growing appreciation of the need for effective research (NIMH, 2011). Clinical researchers have tried to determine which concepts best explain and predict abnormal behavior, which treatments are most effective, and what kinds of changes may be required. Well-

Technology and Mental Health

Technology is always changing and, like most other fields, the mental health field is in the position of trying to keep pace with that change. This is not a new state of affairs. Technological change occurred 25, 50, 100 years ago and beyond. What is new, however, is the breathtaking rate of technological change that characterizes today’s world. This growth has begun to have significant effects—

Let’s consider just a small sample of the ways that the mental health field has been affected by recent technological advances. You will come across these and many others throughout the textbook.

Our digital world provides new triggers and vehicles for the expression of abnormal behavior. As you’ll see in Chapter 12, for example, many individuals who grapple with gambling disorder have found the ready availability of Internet gambling to be all too inviting. Similarly, the Internet, texting, and social media have become convenient tools for those who wish to stalk or bully others, express sexual exhibitionism, or pursue pedophilic desires (Taylor & Quayle, 2010). Likewise, some clinicians believe that violent video games may contribute to the development of antisocial behavior, and perhaps even to the onset of conduct disorders among children and teenagers (Zhuo, 2010). And, in the opinion of many clinicians, constant texting, tweeting, and Internet browsing may contribute to shorter attention spans and establish a foundation for attention problems (Richtel, 2010).

24

BETWEEN THE LINES

Public Opinion: Who is “Mentally Ill”?

According to surveys, 2 percent of the public believe that people who see a therapist are mentally ill.

Approximately 37 percent believe that individuals who are prescribed medications by a psychiatrist are mentally ill.

Around 44 percent believe voluntary patients in a mental hospital are mentally ill.

Around 70 percent believe that involuntary patients in a mental hospital are mentally ill.

(Miller, 2014)

A number of clinicians also worry that social networking can contribute to psychological dysfunctioning in certain cases. On the positive side, research indicates that, on average, social media users maintain more close relationships than other people do, receive more social support, are more trusting and open to differing points of view, and are more likely to participate in groups and lead active lives (Hampton et al., 2011; Rainie et al., 2011). On the negative side, however, there is research suggesting that social networking sites may provide a new venue for peer pressure that increases social anxiety in some adolescents (Charles, 2011; Hampton et al., 2011). The sites may, for example, cause some people to develop fears that others in their network will exclude them socially. Similarly, there is clinical concern that sites such as Facebook may facilitate shy or socially anxious people’s withdrawal from valuable face-

In addition, the face of clinical treatment is constantly changing in our fastmoving digital world. The use of cybertherapy, for example, is growing by leaps and bounds as a treatment option (Carrard et al., 2011; Pope & Vasquez, 2011). As you’ll see in Chapter 3, cybertherapy takes such forms as long-

cybertherapy The use of computer technology, such as Skype or avatars, to provide therapy.

cybertherapy The use of computer technology, such as Skype or avatars, to provide therapy.

MindTech

Mental Health Apps Explode in the Marketplace

About a decade ago, some clinicians and researchers began using text messages to help track the behaviors, thoughts, and emotions of clients with psychological problems (Bauer, 2003). That pioneering work has mushroomed into an industry of smartphone apps that often help provide mental health assistance to consumers (Sifferlin, 2013). There are, in fact, now thousands of such apps in the marketplace—

Many of these apps provide individuals with mental health education and resources; others help users to keep track of their shifting moods, thoughts, and bodily changes (called biometrics); still others are interactive and are designed to serve as co-

What kinds of problems might result from the growing availability and use of mental health apps in today’s world?

Many of today’s apps are promising (Konrath, 2013), and they have increasingly been recommended by therapists and mental health researchers, and even by the National Institutes of Health. But, be aware, most of them are unregulated. Only in the past year has the FDA announced its intention to systematically regulate smartphone apps that monitor health and mental health (Alter, 2013). In the meantime, in the absence of regulation and proper research, consumers and therapists alike would be wise to investigate the reputation, manufacturer, content, and therapeutic principles of apps that they are considering (Sifferlin, 2013). ![]()

25

BETWEEN THE LINES

Famous Psych Lines from the Movies

“She wore the gloves all the time, so I just thought, maybe she has a thing about dirt.” (Frozen, 2013)

“I opened up to you and you judged me.” (Silver Linings Playbook, 2012)

“I just want to be perfect.” (Black Swan, 2010)

“Take baby steps.” (What About Bob? 1991)

“I see dead people.” (The Sixth Sense, 1999)

“I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” (Apocalypse Now, 1979)

“Snakes. Why’d it have to be snakes?” (Raiders of the Lost Ark, 1981)

Unfortunately, as you’ll also see throughout the book, the cybertherapy movement is not without its problems. Along with the wealth of mental health information now available online comes an enormous amount of misinformation about psychological problems and their treatments, offered by persons and sites that at best, are far from knowledgeable. Similarly, the issue of quality control is a major problem for Internet-