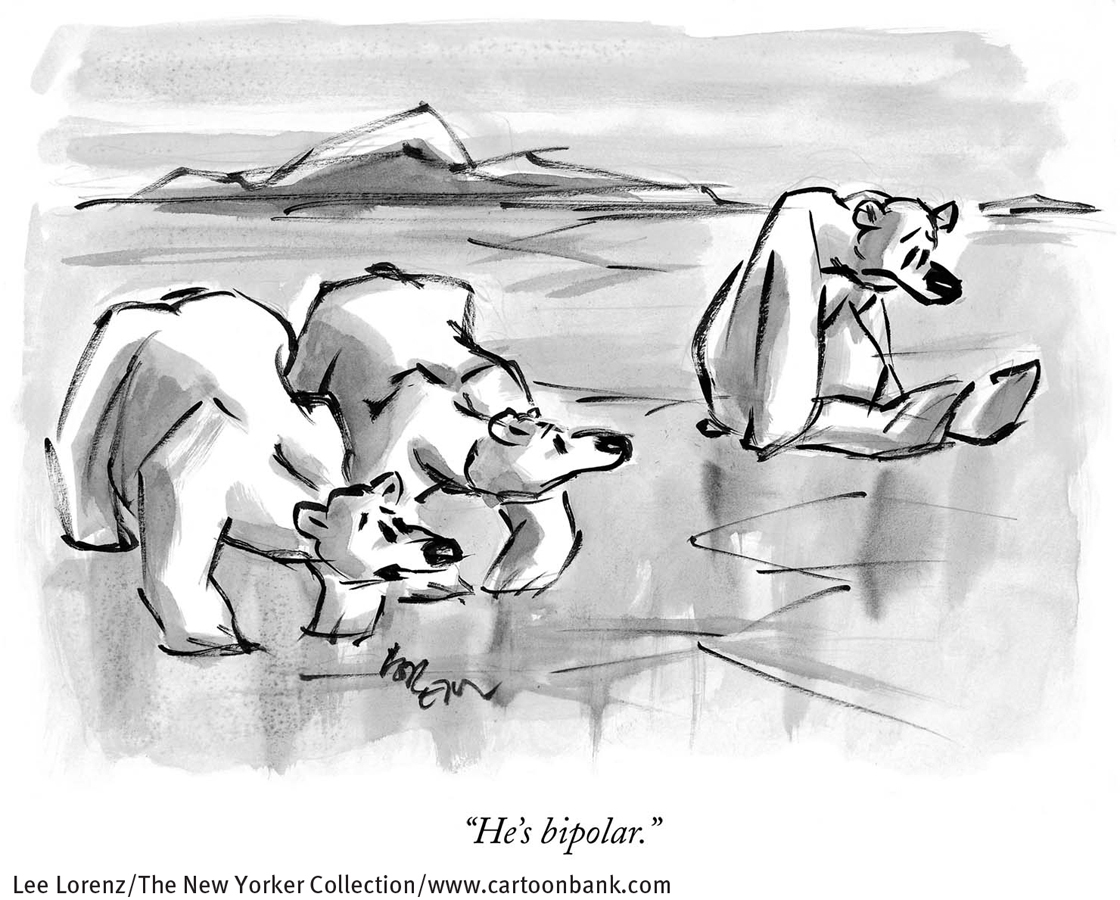

7.3 Bipolar Disorders

People with a bipolar disorder experience both the lows of depression and the highs of mania. Many describe their life as an emotional roller coaster, as they shift back and forth between extreme moods. A number of sufferers eventually become suicidal. Their roller coaster ride also has a dramatic impact on relatives and friends (Barron et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2011; Lowe & Cohen, 2010).

What Are the Symptoms of Mania?

Unlike people sunk in the gloom of depression, those in a state of mania typically experience dramatic and inappropriate rises in mood. The symptoms of mania span the same areas of functioning—

A person in the throes of mania has active, powerful emotions in search of an outlet. The mood of euphoric joy and well-

In the motivational realm, people with mania seem to want constant excitement, involvement, and companionship. They enthusiastically seek out new friends and old, new interests and old, and have little awareness that their social style is overwhelming, domineering, and excessive.

241

The behavior of people with mania is usually very active. They move quickly, as though there were not enough time to do everything they want to do. They may talk rapidly and loudly, their conversations filled with jokes and efforts to be clever or, conversely, with complaints and verbal outbursts. Flamboyance is not uncommon: dressing in flashy clothes, giving large sums of money to strangers, or even getting involved in dangerous activities.

BETWEEN THE LINES

Frenzied Masterpiece

George Frideric Handel wrote his Messiah in less than a month during a manic episode (Roesch, 1991).

In the cognitive realm, people with mania usually show poor judgment and planning, as if they feel too good or move too fast to consider possible pitfalls. Filled with optimism, they rarely listen when others try to slow them down, interrupt their buying sprees, or prevent them from investing money unwisely. They may also hold an inflated opinion of themselves, and sometimes their self-

Finally, in the physical realm, people with mania feel remarkably energetic. They typically get little sleep yet feel and act wide awake (Armitage & Arnedt, 2011). Even if they miss a night or two of sleep, their energy level may remain high.

Diagnosing Bipolar Disorders

People are considered to be in a full manic episode when for at least 1 week they display an abnormally high or irritable mood, increased activity or energy, and at least three other symptoms of mania (see Table 7-5). The episode may even include psychotic features such as delusions or hallucinations. When the symptoms of mania are less severe (causing little impairment), the person is said to be having a hypomanic episode (APA, 2013).

|

Manic Episode |

|

|

1. |

For 1 week or more, person displays a continually abnormal, inflated, unrestrained, or irritable mood as well as continually heightened energy or activity, for most of every day. |

|

2. |

Person also experiences at least three of the following symptoms: • Grandiosity or overblown self- |

|

3. |

Significant distress or impairment. |

|

Bipolar I Disorder |

|

|

1. |

Occurrence of a manic episode. |

|

2. |

Hypomanic or major depressive episodes may precede or follow the manic episode. |

|

Bipolar II Disorder |

|

|

1. |

Presence or history of major depressive episode(s). |

|

2. |

Presence or history of hypomanic episode(s). |

|

3. |

No history of a manic episode. |

|

Information from: APA, 2013. |

|

242

BETWEEN THE LINES

Clinical Oversight

Around 70 percent of people with a bipolar disorder are misdiagnosed at least once (Statistic Brain, 2012).

DSM-

bipolar I disorder A type of bipolar disorder marked by full manic and major depressive episodes.

bipolar I disorder A type of bipolar disorder marked by full manic and major depressive episodes.

bipolar II disorder A type of bipolar disorder marked by mildly manic (hypo-

bipolar II disorder A type of bipolar disorder marked by mildly manic (hypo-

Without treatment, the mood episodes tend to recur for people with either type of bipolar disorder. If a person has four or more episodes within a one-

This illness is about being trapped by your own mind and body. It’s about loss of control over your life. … To onlookers it seems that your whole personality has changed; the person they know is no longer in evidence. …

My mood may swing from one part of the day to another. I may wake up low at 10 am, but be high and excitable by 3 pm. I may not sleep for more than 2 hours one night, being full of creative energy, but by midday be so fatigued it is an effort to breathe.

If my elevated states last more than a few days, my spending can become uncontrollable … I remember being entranced by 18-

I will sometimes drive faster than usual, need less sleep and can concentrate well, making quick and accurate decisions. At these times I can also be sociable, talkative and fun, focused at times, distracted at others. If this state of elevation continues I often find that feelings of violence and irritability towards those I love will start to creep in. …

My thoughts speed up and I can lie in bed for hours at a time watching pictures on the inner sides of my eyelids. … I frequently want to be able to achieve several tasks at the same moment. I may want to read two novels, listen to music and write poetry all simultaneously becoming rapidly frustrated that I cannot do this.

Physically my energy levels can seem limitless. The body moves smoothly, there is little or no fatigue. I can go mountain biking all day when I feel like this and if my mood stays elevated not a muscle is sore or stiff the next day. But it doesn’t last, my elevated phases are short … the shift into severe depression or a mixed mood state occurs sometimes within minutes or hours, often within days and will last weeks often without a period of normality. Indeed I often lose track of what normality is.

Initially my thoughts become disjointed and start slithering all over the place. … They will sometimes remain rapid and are accompanied by paranoid delusions … I start to believe that others are commenting adversely on my appearance or behaviour. I can become very frightened and antisocial. … My sleep will be poor and interrupted by bad dreams. I will change from being the person who has the ideas—

The world appears bleak and a pointless round of social niceties. I will wear my most comfortable, often black clothes, everything else grazes and chafes at my skin.

I become repelled by the proximity of people, acutely aware of interpersonal spaces that have somehow grown closer around me. I will be overwhelmed by the slightest tasks, even imagined tasks. … Physically there is immense fatigue: my muscles scream with pain… I ache down to my bone marrow, my joints feel swollen. … The exhaustion becomes so complete that eventually I drop into bed fully clothed. … I will often sleep without being refreshed for up to 18 hours. … Food becomes totally uninteresting or takes on a repulsive flavour, so I will lose weight rapidly during a long depressive phase. …

243

I become unable to concentrate to read a novel for pleasure, for escape. … I start to feel trapped, that the only escape is death. … My brain slows right down. I become stuck, unable to answer a simple question, unable to establish eye contact and unable to comprehend what is being asked of me.

I avoid answering the phone or the door. My voice deepens and slows sometimes to the point of slurring. …

As I begin to slip into a more psychotic state of mind I become unable to recognise something as familiar as the palm of my hand or my children’s faces. … Those I love around me become part of a conspiracy to harm me. … Twisted tales and delusions.

I become passionate about one subject only at these times of deep and intense fear, despair and rage: suicide. … I have made close attempts on my life … over the last few years. …

Then inexplicably, my mood will shift again. The fatigue drops from my limbs like shedding a dead weight, my thinking returns to normal, the light takes on an intense clarity, flowers smell sweet and my mouth curves to smile at my children, my husband and I am laughing again. Sometimes it’s for only a day but I am myself again, the person that I was a frightening memory. I have survived another bout of this dreaded disorder. …

This illness is about having to live life at its extremes of physical and mental endurance, having to go to places that most people never experience, would never want to experience. It has been about having unthought of limitations placed on your life, your career, your family. … It has become about trying to stay alive and living life fully in the brief periods of normality or mild elevation that occur from time to time.

Otherwise, rapid cycling bipolar disorder is an unrelenting scourge.

(Anonymous, 2006)

Regardless of their particular pattern, people with a bipolar disorder tend to experience depression more than mania over the years (Advokat et al., 2014). In most cases, their depressive episodes occur three times as often as manic ones, and the depressive episodes also last longer.

Surveys from around the world indicate that between 1 and 2.6 percent of all adults are suffering from a bipolar disorder at any given time (Kessler et al., 2012; Merikangas et al., 2011). As many as 4 percent experience one of the bipolar disorders at some time in their life. Bipolar I disorder seems to be a bit more common than bipolar II disorder. The bipolar disorders are equally common in women and men. However, women may have more depressive episodes and more rapid cycling than men (Curtis, 2005; Papadimitriou et al., 2005). The disorders are more common among people with low incomes than those with higher incomes (Sareen et al., 2011).

Onset of bipolar disorder usually occurs between the ages of 15 and 44 years. In most untreated cases, the manic and depressive episodes eventually subside, only to recur at a later time. It also appears that over time, people with bipolar disorders develop more medical ailments than the rest of the population (Weiner, Warren, & Fiedorowitz, 2011).

Some people have numerous periods of hypomanic symptoms and mild depressive symptoms, a pattern that is called cyclothymic disorder in DSM-

cyclothymic disorder A disorder marked by numerous periods of hypo-

cyclothymic disorder A disorder marked by numerous periods of hypo-

244

PsychWatch

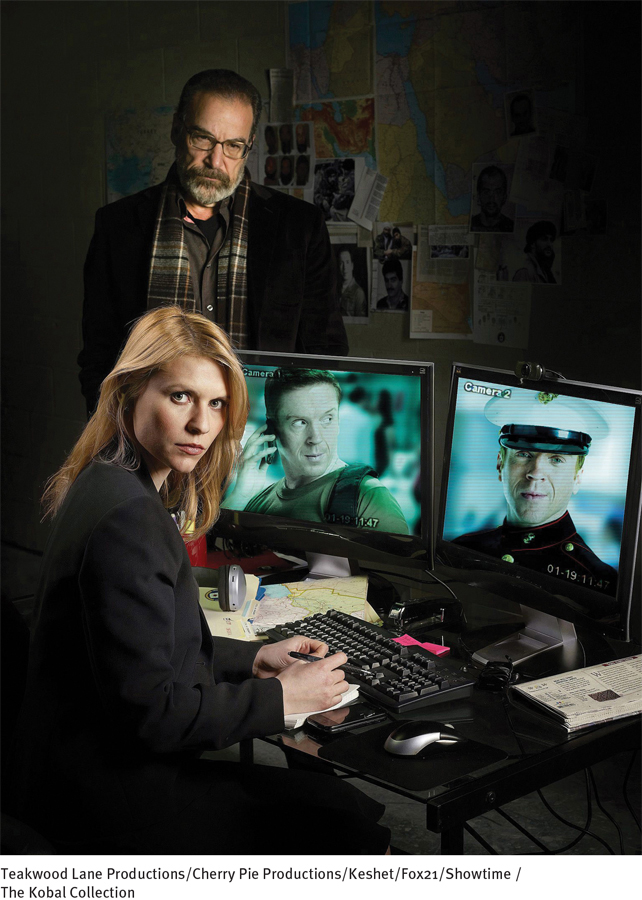

Abnormality and Creativity: A Delicate Balance

Up to a point, states of depression, mania, anxiety, and even confusion can be useful. This may be particularly true in the arts. The ancient Greeks believed that various forms of “divine madness” inspired creative acts, from poetry to performance (Ludwig, 1995). Even today many people expect “creative geniuses” to be psychologically disturbed. A popular image of the artist includes a glass of liquor, a cigarette, and a tormented expression. Classic examples include writer William Faulkner, who suffered from alcoholism and received electroconvulsive therapy for depression; poet Sylvia Plath, who was depressed for most of her life and eventually committed suicide at age 31; and dancer Vaslav Nijinsky, who suffered from schizophrenia and spent many years in institutions. In fact, a number of studies indicate that artists and writers are somewhat more likely than others to suffer from certain mental disorders, particularly bipolar disorders (Kyaga et al., 2013, 2011;Galvez et al., 2011; Simonton, 2010; Sample, 2005).

Why might creative people be prone to such psychological disorders? Some may be predisposed to such disorders long before they begin their artistic careers; the careers may simply bring attention to their emotional struggles (Simonton, 2010; Ludwig, 1995). Indeed, creative people often have a family history of psychological problems (Kyaga et al., 2013, 2011). A number also have experienced intense psychological trauma during childhood. English novelist and essayist Virginia Woolf, for example, endured sexual abuse as a child.

Another reason for the creativity link may be that creative endeavors create emotional turmoil that is overwhelming. Truman Capote said that writing his famous book In Cold Blood “killed” him psychologically. Before writing this account of the brutal murders of a family, he considered himself “a stable person. …Afterward something happened to me” (Ludwig, 1995).

Yet a third explanation for the link between creativity and psychological disorders is that the creative professions offer a welcome climate for those with psychological disturbances. In the worlds of poetry, painting, and acting, for example, emotional expression, unusual thinking, and/or personal turmoil are valued as sources of inspiration and success (Galvez et al., 2011; Sample, 2005; Ludwig, 1995).

Much remains to be learned about the relationship between emotional turmoil and creativity, but work in this area has already clarified two important points. First, psychological disturbance is hardly a requirement for creativity. Most “creative geniuses” are, in fact, psychologically stable and relatively happy throughout their entire lives (Kaufman, 2013). Second, mild psychological disturbances relate to creative achievement much more strongly than severe disturbances do (Galvez et al., 2011; Simonton, 2010). For example, nineteenth-

Some artists worry that their creativity would disappear if their psychological suffering were to stop. In fact, however, research suggests that successful treatment for severe psychological disorders more often than not improves the creative process (Jamison, 1995; Ludwig, 1995). Romantic notions aside, severe mental dysfunctioning has little redeeming value, in the arts or anywhere else.

245

What Causes Bipolar Disorders?

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the search for the cause of bipolar disorders made little progress. Various explanations were proposed, but research did not support their validity. Psychodynamic theorists, for example, suggested that mania, like depression, emerges from the loss of a love object. Whereas some people introject the lost object and become depressed, others deny the loss and become manic. To avoid the terrifying conflicts generated by the loss, they escape into a dizzying round of activity (Lewin, 1950). Although case reports sometimes fit this explanation, only a few controlled studies have found a relationship between loss early or later in life and the onset of manic episodes (Post & Miklowitz, 2010; Tsuchiya et al., 2005).

More recently, biological research has produced some promising clues. The biological insights have come from research into neurotransmitter activity, ion activity, brain structure, and genetic factors.

NeurotransmittersRemember from Chapter 3 that neurotransmitters released from neurons’ axon endings carry messages to the dendrites of neighboring neurons by binding to receptor sites there. As you read, different psychological disorders have been linked to the abnormal functioning of various neurotransmitters, including norepinephrine. Could overactivity of norepinephrine be related to mania? This was the expectation of clinicians back in the 1960s after investigators first found a relationship between low norepinephrine activity and unipolar depression (Schildkraut, 1965). One study did indeed find the norepinephrine activity of people with mania to be higher than that of depressed or control research participants (Post et al., 1980, 1978). In another study, patients with a bipolar disorder were given reserpine, the blood pressure drug known to reduce norepinephrine activity in the brain, and the manic symptoms of some subsided (Telner et al., 1986).

BETWEEN THE LINES

What Is Hypergraphia?

Hypergraphia refers to a compulsive need to write. During severe episodes, people with this rare problem write constantly, not only filling up notebooks or computer screens but also feverishly finding unusual writing surfaces, including their own skin. The problem has been linked to several disorders, including bipolar disorders, temporal lobe epilepsy, and schizophrenia. There is speculation that some famous writers and artists worked under the sway of hypergraphia, such as prolific author Fyodor Dostoyevski and painter Vincent van Gogh, who produced an endless stream of paintings and letters.

Because serotonin activity often parallels norepinephrine activity in unipolar depression, theorists at first expected that mania would also be related to high serotonin activity, but no such relationship has been found. Instead, research suggests that mania, like depression, may be linked to low serotonin activity (Hsu et al., 2014; Nugent et al., 2013). Perhaps low activity of serotonin, acting again as a neuromodulator, opens the door to a mood disorder and permits the activity of norepinephrine (or perhaps other neurotransmitters) to define the particular form the disorder will take. That is, low serotonin activity accompanied by low norepinephrine activity may lead to depression; low serotonin activity accompanied by high norepinephrine activity may lead to mania. In recent years, researchers have found that bipolar disorder may also be tied to the abnormal activity of other neurotransmitters, such as GABA, the brain chemical you read about in Chapter 5 (Benes, 2011; Walderhaug et al., 2011).

246

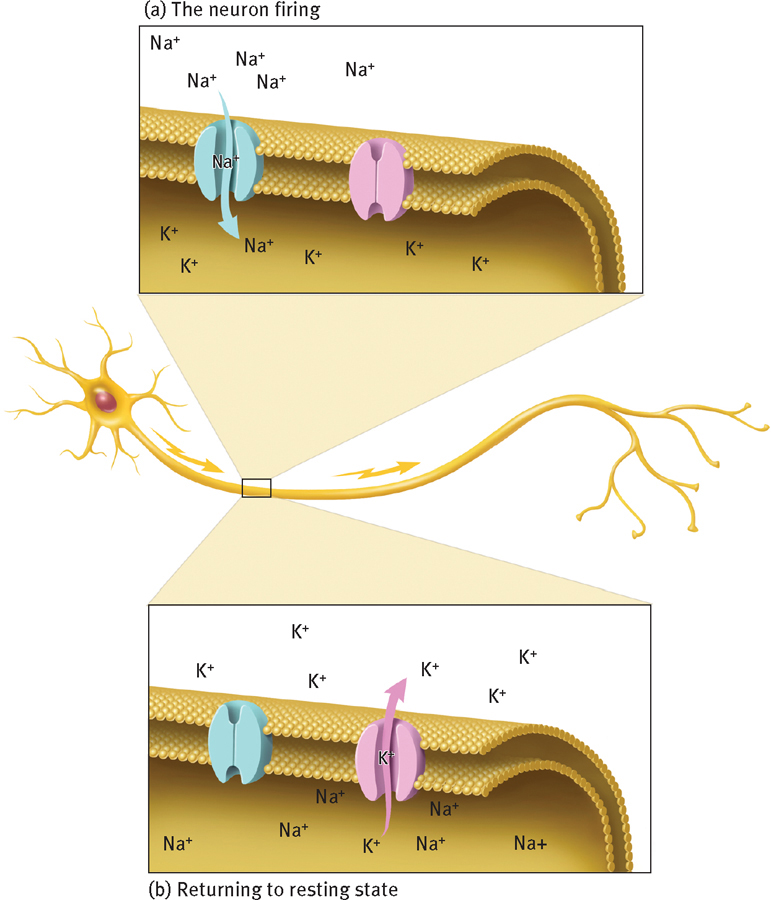

Ion ActivityWhile neurotransmitters play a significant role in the communication between neurons, ions seem to play a critical role in relaying messages within a neuron. That is, ions help transmit messages down the neuron’s axon to the nerve endings. Positively charged sodium ions (Na+) sit on both sides of a neuron’s cell membrane. When the neuron is at rest, more sodium ions sit outside the membrane. When the neuron receives an incoming message at its receptor sites, pores in the cell membrane open, allowing the sodium ions to flow to the inside of the membrane, thus increasing the positive charge inside the neuron. This starts a wave of electrical activity that travels down the length of the neuron and results in its “firing.” After the neuron “fires,” potassium ions (K+) flow from the inside of the neuron across the cell membrane to the outside, helping to return the neuron to its original resting state (see Figure 7-4).

Ions and the firing of neurons

Neurons relay messages in the form of electrical impulses that travel down the axon toward the nerve endings. As an impulse travels along the axon, sodium ions (Na+), on the outside of the neuron’s membrane, flow inside, causing the impulse to continue down the axon. Once sodium ions flow in, potassium ions (K+) flow out, returning the membrane’s electrical balance to its resting state, ready for the arrival of a new impulse.

If messages are to be relayed effectively down the axon, the ions must be able to travel easily between the outside and the inside of the neural membrane. Some theorists believe that irregularities in the transport of these ions may cause neurons to fire too easily (resulting in mania) or to stubbornly resist firing (resulting in depression) (Manji & Zarate, 2011; Li & El-

247

Brain StructureBrain imaging and postmortem studies have identified a number of abnormal brain structures in people with bipolar disorders (Eker et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2011; Savitz & Drevets, 2011). For example, the basal ganglia and cerebellum of these people tend to be smaller than those of other people, they have lower volumes of gray matter in the brain, and their dorsal raphe nucleus, striatum, amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex have some structural abnormalities. It is not clear what role such structural abnormalities play in bipolar disorders. It may be that they help produce the neurotransmitter and ion abnormalities that you read about earlier. The dorsal raphe nucleus, for example, is one of the brain sites where serotonin is produced. Alternatively, the structural problems may simply be the result of the neurotransmitter or ion abnormalities or of the medications that many patients with bipolar disorders now take.

Genetic FactorsMany theorists believe that people inherit a biological predisposition to develop bipolar disorders (Wiste et al., 2014; Glahn & Burdick, 2011; Gershon & Nurnberger, 1995). Family pedigree studies support this idea. Identical twins of those with a bipolar disorder have a 40 percent likelihood of developing the same disorder, and fraternal twins, siblings, and other close relatives of such persons have a 5 to 10 percent likelihood, compared with the 1 to 2.6 percent prevalence rate in the general population.

Researchers have also conducted genetic linkage studies to identify possible patterns in the inheritance of bipolar disorders. They select large families that have had high rates of a disorder over several generations, observe the pattern of distribution of the disorder among family members, and determine whether it closely follows the distribution pattern of a known genetically transmitted family trait (called a genetic marker), such as color blindness, red hair, or a particular medical syndrome.

248

BETWEEN THE LINES

Criminal Conduct

People with bipolar disorder are more likely than other people to engage in criminal behaviors, particularly during manic episodes (Swann et al., 2011).

After studying the records of Israeli, Belgian, Italian, and Finnish families that had high rates of bipolar disorders across several generations, several researchers seemed to have linked bipolar disorders to genes on the X chromosome (Ekholm et al., 2002; Mendlewicz et al., 1987, 1980). Other research teams, however, later used techniques from molecular biology to examine genetic patterns in large families, and they linked bipolar disorders to genes on chromosomes 1, 4, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 18, 20, 21, and 22 (Green et al., 2013; Bigdeli et al., 2013; Wendland and McMahon, 2011). Such wide-