7.4 PUTTING IT...together

Making Sense of All That Is Known

With mood problems so prevalent in all societies, it is no wonder that moods have been the focus of so much research. Great quantities of data have been gathered about moods—

Research participants often prefer listening to sad songs over happy songs, even though they make them depressed. Why?

Several factors have been tied closely to unipolar depression, including biological abnormalities, a reduction in positive reinforcements, negative ways of thinking, a perception of helplessness, and life stress and other sociocultural influences. Indeed, more contributing factors have been associated with unipolar depression than with most other psychological disorders. Precisely how all of these factors relate to unipolar depression, however, is unclear. Several relationships are possible:

BETWEEN THE LINES

The Color of Depression

In Western society, black is often the color of choice in describing depression. British prime minister Winston Churchill called his recurrent episodes a “black dog always waiting to bare its teeth.” American novelist Ernest Hemingway referred to his bouts as “black-

One of the factors may be the key cause of unipolar depression. That is, one theory may be more useful than any of the others for predicting and explaining how unipolar depression occurs. If so, cognitive or biological factors are leading candidates, for these kinds of factors have each been found, at times, to precede and predict depression.

Different factors may be capable of initiating unipolar depression in different people (Goldstein et al., 2011). Some people may, for example, begin with low serotonin activity, which predisposes them to react helplessly in stressful situations, interpret events negatively, and enjoy fewer pleasures in life. Others may first suffer a severe loss, which triggers helplessness reactions, low serotonin activity, and reductions in positive rewards. Regardless of the initial cause, these factors may merge into a “final common pathway” of unipolar depression.

An interaction between two or more specific factors may be necessary to produce unipolar depression. Perhaps people will become depressed only if they have low levels of serotonin activity, feel helpless, and repeatedly blame themselves for negative events.

The various factors may play different roles in unipolar depression. Some may cause the disorder, some may result from it, and some may keep it going. Peter Lewinsohn and his colleagues (1988) assessed more than 500 nondepressed persons on the various factors linked to depression. They then assessed the study’s participants again 8 months later to see who had in fact become depressed and which of the factors had predicted depression. Negative thinking, self-

dissatisfaction, and life stress were found to precede and predict depression; poor social relationships and reductions in positive rewards did not. The researchers concluded that the former factors help cause unipolar depression, while the latter simply accompany or result from depression and perhaps help maintain it.

249

InfoCentral

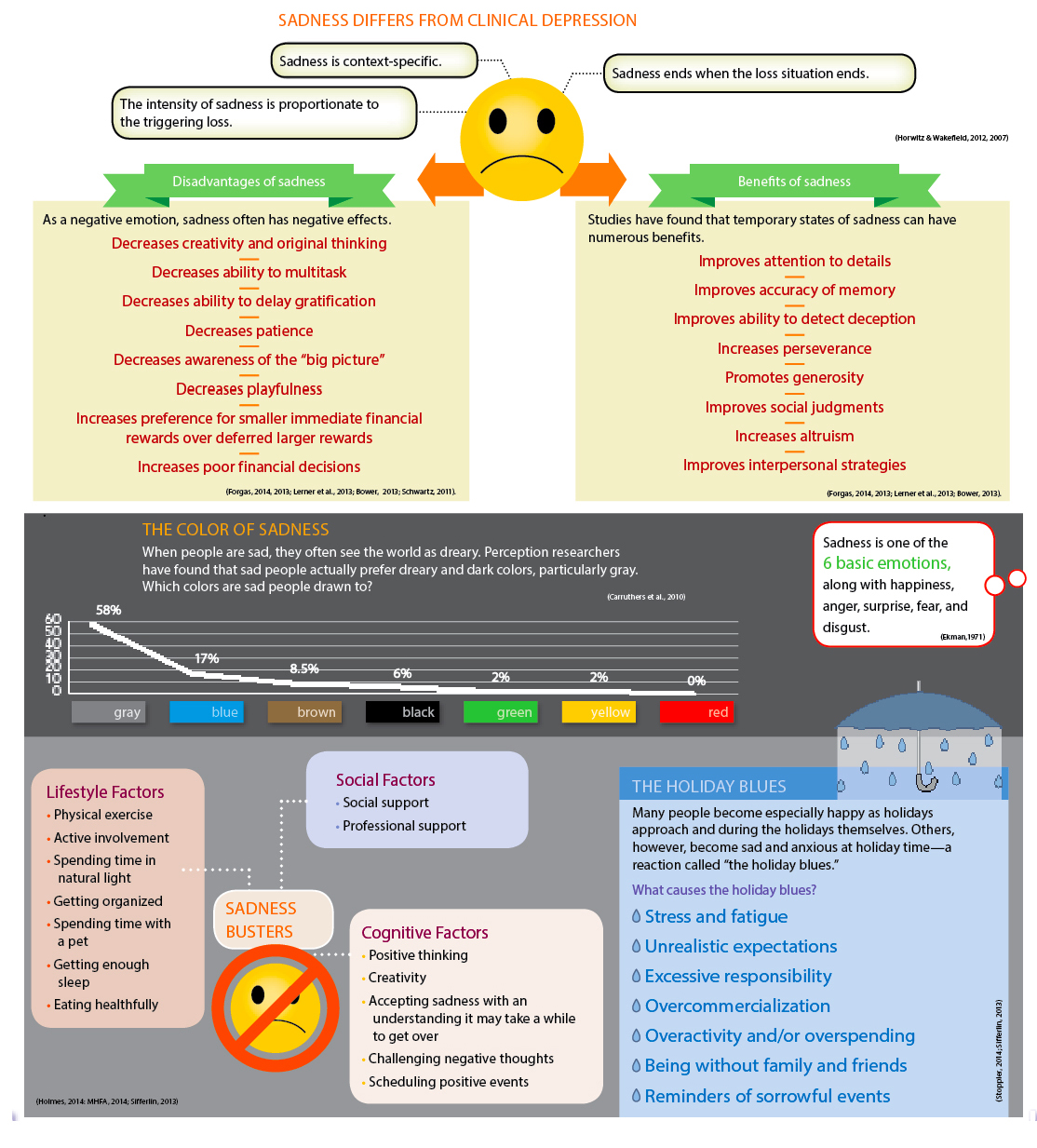

SADNESS

Depression, a clinical disorder that causes considerable distress and impairment, features a range of symptoms, including emotional, motivational, behavioral, cognitive, and physical symptoms. Sadness is often one of the symptoms found in depression, but most often it is a perfectly normal negative emotion triggered by a loss or other painful circumstance.

250

CLINICAL CHOICES

Now that you’ve read about disorders of mood, try the interactive case study for this chapter. See if you are able to identify John’s symptoms and suggest a diagnosis based on his symptoms. What kind of treatment would be most effective for John? Go to LaunchPad to access Clinical Choices.

As with unipolar depression, clinicians and researchers have learned much about bipolar disorders during the past 35 years. But bipolar disorders appear to be best explained by a focus on one kind of variable—

Thus we see in this chapter that one kind of disorder may result from multiple causes, while another may result largely from a single factor. Although today’s theorists are increasingly looking for intersecting factors to explain various psychological disorders, this is not always the most enlightening course. It depends on the disorder. What is important is that the cause or causes of a disorder be recognized. Scientists can then invest their energies more efficiently and clinicians can better understand the persons with whom they work.

There is no question that investigations into the symptoms and causes of depressive and bipolar disorders have been fruitful and enlightening. And it is more than reasonable to expect that important research findings and insights will continue to unfold in the years ahead. Now that clinical researchers have gathered so many important pieces of the puzzle, they must put the pieces together into a still more meaningful picture that will suggest even better ways to predict, prevent, and treat these disorders.

DSM-5 CONTROVERSY

Does Bereavement Equal Depression?

In past editions of the DSM, people who lose a loved one were excluded from receiving a diagnosis of major depressive disorder during the first 2 months of their bereavement. However, according to DSM-

BETWEEN THE LINES

In Their Words

“No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.”

Eleanor Roosevelt

SUMMING UP

DEPRESSIVE VERSUS BIPOLAR DISORDERS People with depressive disorders and bipolar disorders have mood problems that tend to last for months or years, dominate their interactions with the world, and disrupt their normal functioning. Those with depressive disorders grapple with depression only, called unipolar depression. Those with bipolar disorders contend with both depression and mania. p. 216

UNIPOLAR DEPRESSION: THE DEPRESSIVE DISORDERS People with uni-

polar depression, the most common pattern of mood difficulty, suffer exclusively from depression. The symptoms of depression span five areas of functioning: emotional, motivational, behavioral, cognitive, and physical. Depressed people are also at higher risk for suicidal thinking and behavior. Women are at least twice as likely as men to experience severe unipolar depression. pp. 216– 222 EXPLANATIONS OF UNIPOLAR DEPRESSION Each of the leading models has offered explanations for unipolar depression. The biological, cognitive, and sociocultural views have received the most research support.

According to the biological view, low activity of two neurotransmitters, norepinephrine and serotonin, helps cause depression. Hormonal factors may also be at work. So too may deficiencies of key proteins and other chemicals within certain neurons. Brain imaging research has also tied depression to abnormalities in a circuit of brain areas, including the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, the amygdala, and Brodmann Area 25. All such biological problems may be linked to genetic factors.

According to the psychodynamic view, certain people who experience real or imagined losses may regress to an earlier stage of development, introject feelings for the lost object, and eventually become depressed.

The behavioral view says that when people experience a large reduction in their positive rewards in life, they may display fewer and fewer positive behaviors. This response leads to a still lower rate of positive rewards and eventually to depression.

251

The leading cognitive explanations of unipolar depression focus on negative thinking and learned helplessness. According to Beck’s theory of negative thinking, maladaptive attitudes, the cognitive triad, errors in thinking, and automatic thoughts help produce unipolar depression. According to Seligman’s learned helplessness theory, people become depressed when they believe that they have lost control over the reinforcements in their lives and when they attribute this loss to causes that are internal, global, and stable.

Sociocultural theorists propose that unipolar depression is influenced by social and cultural factors. Family-

social theorists point out that a low level of social support is often linked to unipolar depression. And multicultural theorists have noted that the character and prevalence of depression often vary by gender and sometimes by culture. pp. 222– 240 BIPOLAR DISORDERS In bipolar disorders, episodes of mania alternate or intermix with episodes of depression. These disorders are much less common than unipolar depression. They may take the form of bipolar I, bipolar II, or cyclothymic disorder. pp. 240–

244 EXPLANATIONS OF BIPOLAR DISORDERS Mania may be related to high norepinephrine activity along with a low level of serotonin activity. Some researchers have also linked bipolar disorders to improper transport of ions back and forth between the outside and the inside of a neuron’s membrane; others have focused on deficiencies of key proteins and other chemicals within certain neurons; and still others have uncovered abnormalities in key brain structures. Genetic studies suggest that people may inherit a predisposition to these biological abnormalities. pp. 245–

248

Visit LaunchPad

www.macmillanhighered.com/