9.5 Treatment and Suicide

Treatment of suicidal people falls into two major categories: treatment after suicide has been attempted and suicide prevention. Treatment may also be beneficial to relatives and friends of those who commit or attempt to commit suicide. Indeed, their feelings of loss, guilt, and anger after a suicide fatality or attempt can be intense (Feigelman & Feigelman, 2011). However, the discussion here is limited to the treatment afforded suicidal people themselves.

308

InfoCentral

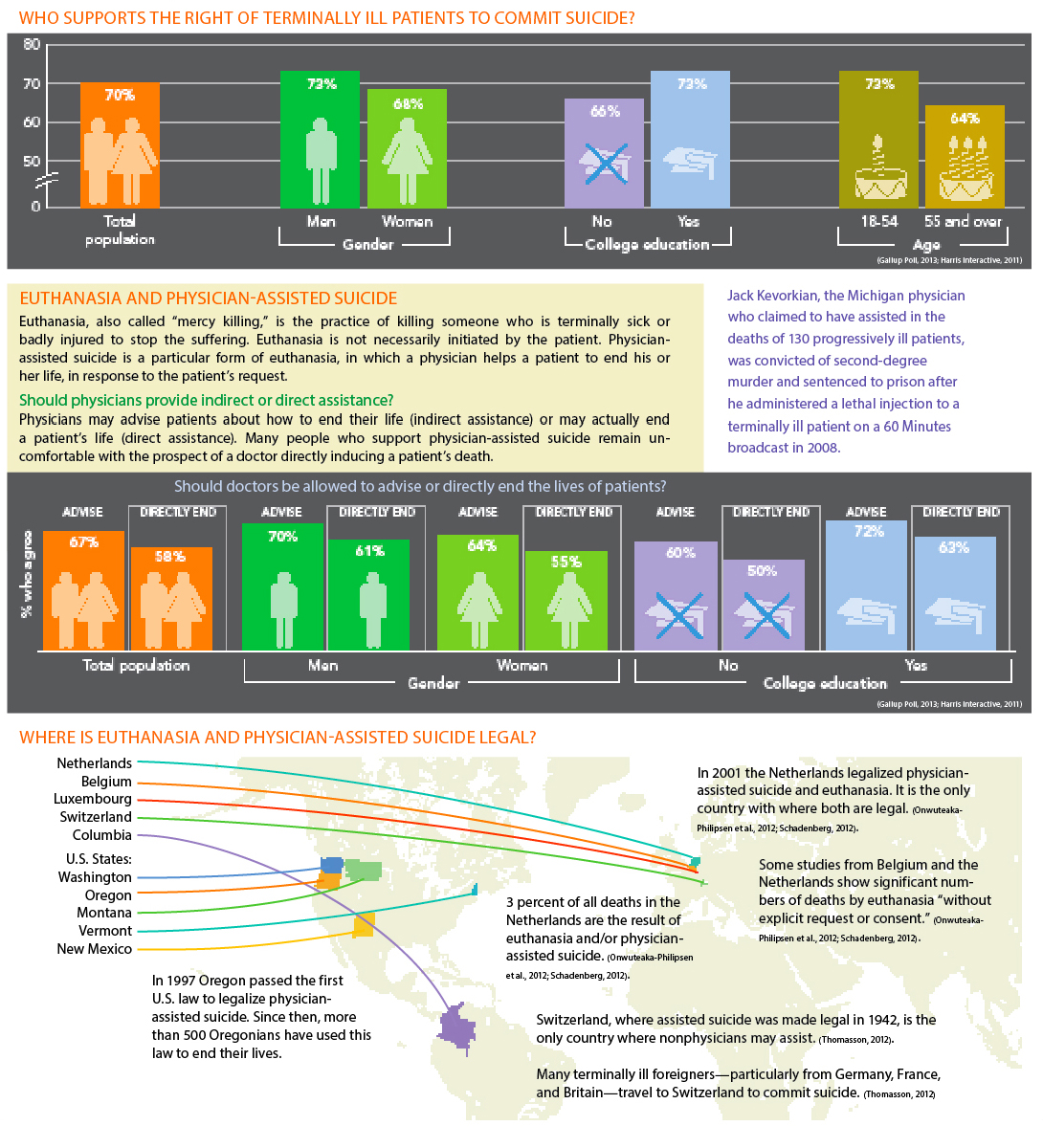

THE RIGHT TO COMMIT SUICIDE

In ancient Greece, citizens with a grave illness or mental anguish could obtain official permission from the Senate to take their own lives (Humphry & Wickett, 1986). In contrast, most Western countries have traditionally discouraged suicide, based on their belief in the “sanctity of life” (Dickens et al., 2008). Today, however, a person’s “right to commit suicide” is receiving more and more support from the public, particularly in connection with ending great pain and terminal illness (Breitbart et al., 2011; Werth, 2004, 2000).

309

What Treatments Are Used After Suicide Attempts?

After a suicide attempt, most victims need medical care. Close to one-

Unfortunately, even after trying to kill themselves, many suicidal people fail to receive systematic follow-

The goals of therapy for those who have attempted suicide are to keep the individuals alive, reduce their psychological pain, help them achieve a nonsuicidal state of mind, provide them with hope, and guide them to develop better ways of handling stress (Rudd & Brown, 2011). Various therapies have been employed, including drug, psychodynamic, cognitive-

Research indicates that cognitive-

What Is Suicide Prevention?

During the past 50 years, emphasis around the world has shifted from suicide treatment to suicide prevention. In some respects this change is most appropriate: the last opportunity to keep many potential suicide victims alive comes before their first attempt.

The first suicide prevention program in the United States was founded in Los Angeles in 1955; the first in England, called the Samaritans, was started in 1953. There are now hundreds of suicide prevention centers in the United States and England. In addition, many of today’s mental health centers, hospital emergency rooms, pastoral counseling centers, and poison control centers include suicide prevention programs among their services.

suicide prevention program A program that tries to identify people who are at risk of killing themselves and to offer them crisis intervention.

suicide prevention program A program that tries to identify people who are at risk of killing themselves and to offer them crisis intervention.

There are also hundreds of suicide hotlines, 24-

310

Suicide prevention programs and hotlines respond to suicidal people as individuals in crisis—that is, under great stress, unable to cope, feeling threatened or hurt, and interpreting their situations as unchangeable. Thus the programs offer crisis intervention: they try to help suicidal people see their situations more accurately, make better decisions, act more constructively, and overcome their crises (Lester, 2011). Because crises can occur at any time, the centers advertise their hotlines and also welcome people who walk in without appointments (see MindTech below).

crisis intervention A treatment approach that tries to help people in a psychological crisis to view their situation more accurately, make better decisions, act more constructively, and overcome the crisis.

crisis intervention A treatment approach that tries to help people in a psychological crisis to view their situation more accurately, make better decisions, act more constructively, and overcome the crisis.

Some prevention centers and hotlines reach out to particular suicidal populations. The Trevor Lifeline, for example, is a nationwide, around-

MindTech

Crisis Texting

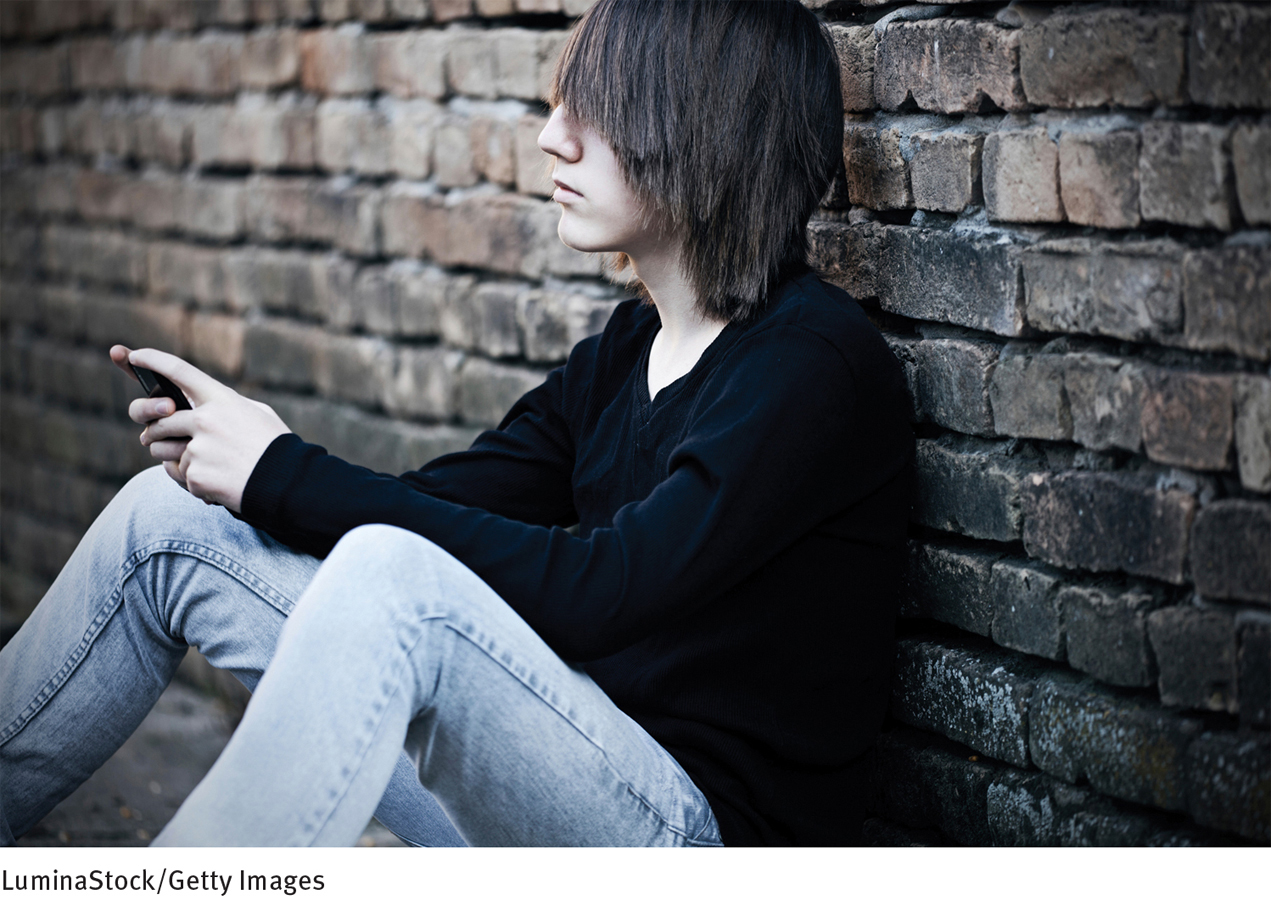

Suicide hotlines and drop-

(1) While it is difficult to create the personal connection that even a phone conversation with a counselor can provide, most people under 20 are very familiar—

(2) If a person’s crisis involves an abusive situation with a family member, the person does not need to wait until he or she is alone to communicate with a counselor. The texter can be in the same room with their abuser, who might not be any the wiser (Lublin, 2014).

(3) Similarly, a person in crisis who might be out in public does not need to wait until alone to seek help. He or she can still look “cool” to peers or friends while receiving desperately needed assistance (Weichman, 2014).

(4) A session conducted by text can be interrupted and picked back up more naturally than a phone conversation. Likewise, a counselor can hand over a session to another expert with less interruption of flow than there would be in a phone conversation.

(5) Because texts are archived, the person in crisis can go back and reread the texts during difficult moments in the future and revisit the advice and coping mechanisms discussed (Weichman, 2014). Also, archived texts may provide valuable data for researchers studying suicide trends, and may lead to unanticipated treatment insights.

What limitations or problems might result from attempts to prevent suicides by the use of texting?

One nonprofit service, the Crisis Text Line in New York, has been offering text counseling since the fall of 2013, in partnership with a number of hotlines across the United States (Kaufman, 2014; Lubin, 2014). In the first half year of operation, it exchanged nearly a million texts with 19,000 teenagers, with only minimal advertising. Google now links users to the Crisis Text Line’s contact information whenever they do searches for suicide-![]()

311

The public sometimes confuses suicide prevention centers and hotlines with online chat rooms and forums (message boards) to which some suicidal people turn. However, such online sites operate quite differently, and in fact, most of them do not seek out suicidal people or try to prevent suicide. Typically, these chat rooms (where users communicate in real time) and forums (where users post messages without interacting directly) are not prepared to deal with suicidal people, do not offer face-

Today, suicide prevention takes place not only at prevention centers and hotlines but also in therapists’ offices. Suicide experts encourage all therapists to look for and address signs of suicidal thinking in their clients, regardless of the broad reasons that the clients are seeking treatment (McGlothlin, 2008). With this in mind, a number of guidelines have been developed to help therapists effectively uncover, assess, prevent, and treat suicidal thinking and behavior in their daily work (Van Orden et al., 2008; Shneidman & Farberow, 1968).

Although specific techniques vary from therapist to therapist and from prevention center to prevention center, the approach developed originally by the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Center continues to reflect the goals and techniques of many clinicians and organizations. During the initial contact at the center, the counselor has several tasks:

BETWEEN THE LINES

Suicides by Rock Musicians: Post–

Jason Thirsk, punk band Pennywise (1996)

Rob Pilatus, pop band Milli Vanilli (1998)

Wendy O. Williams, punk singer (1998)

Screaming Lord Sutch, British rock singer (1999)

Herman Brood, Dutch rock singer (2001)

Elliott Smith, rock singer (2003)

Robert Quine, punk guitarist (2004)

Dave Schulthise, bassist for the Dead Milkmen (2004)

Derrick Plourde, rock drummer (2005)

Vince Welnick, keyboardist for the Tubes and the Grateful Dead (2006)

Brad Delp, lead singer for rock band Boston (2007)

Johnny Lee Jackson, rapper (2008)

Vic Chesnutt, singer-

Mark Linkous, singer-

Ronnie Montrose, guitarist (2012)

Bob Welch, guitarist for Fleetwood Mac (2012)

Establish a Positive Relationship As callers must trust counselors in order to confide in them and follow their suggestions, counselors try to set a positive and comfortable tone for the discussion. They convey that they are listening, understanding, interested, nonjudgmental, and available.

Understand and Clarify the Problem Counselors first try to understand the full scope of the caller’s crisis and then help the person see the crisis in clear and constructive terms. In particular, they try to help callers see the central issues and the transient nature of their crises and recognize the alternatives to suicide.

Assess Suicide Potential Crisis workers at the Los Angeles Suicide Prevention Center fill out a questionnaire, often called a lethality scale, to estimate the caller’s potential for suicide. It helps them determine the degree of stress the caller is under, the caller’s relevant personality characteristics, how detailed the suicide plan is, the severity of symptoms, and the coping resources available to the caller.

Assess and Mobilize the Caller’s Resources Although they may view themselves as ineffectual, helpless, and alone, people who are suicidal usually have many strengths and resources, including relatives and friends. It is the counselor’s job to recognize, point out, and activate those resources.

Formulate a Plan Together the crisis worker and caller develop a plan of action. In essence, they are agreeing on a way out of the crisis, an alternative to suicidal action. Most plans include a series of follow-

Although crisis intervention may be sufficient treatment for some suicidal people, longer-

312

As the suicide prevention movement spread during the 1960s, many clinicians came to believe that crisis intervention techniques should also be applied to problems other than suicide. Crisis intervention has emerged during the past several decades as a respected form of treatment for such wide-

Yet another way to help prevent suicide may be to reduce the public’s access to common means of suicide (Lester, 2011). In 1960, for example, around 12 of every 100,000 people in Britain killed themselves by inhaling coal gas (which contains carbon monoxide). In the 1960s, Britain replaced coal gas with natural gas (which contains no carbon monoxide) as an energy source, and by the mid-

Similarly, ever since Canada passed a law in the 1990s restricting the availability of and access to certain firearms, there has been a decrease in firearm suicides across the country (Leenaars, 2007). Some studies suggest that this decrease has not been displaced by increases in other kinds of suicides; other studies, however, have found an increase in the use of other suicide methods (Caron, Julien, & Huang, 2008). Thus, although many clinicians hope that measures such as gun control, safer medications, better bridge barriers, and car emission controls will lower suicide rates, there is no guarantee that they will.

Do Suicide Prevention Programs Work?

It is difficult for researchers to measure the effectiveness of suicide prevention programs (Sanburn, 2013; Lester, 2011). There are many kinds of programs, each with its own procedures and each serving populations that vary in number, age, and the like. Communities with high suicide risk factors, such as a high elderly population or economic problems, may continue to have higher suicide rates than other communities regardless of the effectiveness of their local prevention centers.

Do suicide prevention centers reduce the number of suicides in a community? Clinical researchers do not know (Sanburn, 2013; Lester, 2011). Studies comparing local suicide rates before and after the establishment of community prevention centers have yielded different findings. Some find a decline in a community’s suicide rates, others no change, and still others an increase (De Leo & Evans, 2004; Leenaars & Lester, 2004). Of course, even an increase may represent a positive impact, if it is lower than the larger society’s overall increase in suicidal behavior.

Do suicidal people contact prevention centers? Apparently only a small percentage do (Sanburn, 2013). Moreover, the typical caller to an urban prevention center appears to be young, African American, and female, whereas the greatest number of suicides are committed by older white men (Maris, 2001; Lester, 2000, 1989, 1972). A key problem is that people who are suicidal do not necessarily admit to or talk about their feelings in discussions with others, even with professionals (Stolberg et al., 2002).

Prevention programs do seem to reduce the number of suicides among those high-

313

Why might some schools be reluctant to offer suicide education programs, especially if they have never experienced a suicide attempt by one of their students?

Many theorists have called for more effective public education about suicide as the ultimate form of prevention, and a number of suicide education programs have emerged. Most of these programs take place in schools and concentrate on students and their teachers (Schilling et al., 2014; Mann & Currier, 2011; Van Orden et al., 2008). There are also a growing number of online sites that provide education about suicide—

The primary prevention of suicide lies in education. The route is through teaching one another and … the public that suicide can happen to anyone, that there are verbal and behavioral clues that can be looked for … and that help is available….

In the last analysis, the prevention of suicide is everybody’s business.

(Shneidman, 1985, p. 238)