2.6 The Sociocultural Model: Family-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Pressures of Poverty

| 94 | Number of victims of violent crime per 1,000 impoverished people |

| 50 | Number of victims per 1,000 middle- |

| 40 | Number of victims per 1,000 wealthy people |

(U.S. Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2011)

Philip Berman is also a social and cultural being. He is surrounded by people and by institutions, he is a member of a family and a cultural group, he participates in social relationships, and he holds cultural values. Such forces are always operating upon Philip, setting rules and expectations that guide or pressure him, helping to shape his behaviors, thoughts, and emotions.

According to the sociocultural model, abnormal behavior is best understood in light of the broad forces that influence an individual. What are the norms of the individual’s society and culture? What roles does the person play in the social environment? What kind of family structure or cultural background is the person a part of? And how do other people view and react to him or her? In fact, the sociocultural model is composed of two major perspectives—

How Do Family-

65

Proponents of the family-

Social Labels and Roles Abnormal functioning can be influenced greatly by the labels and roles assigned to troubled people (Rüsch et al., 2014; Yap et al., 2013). When people stray from the norms of their society, the society calls them deviant and, in many cases, “mentally ill.” Such labels tend to stick. Moreover, when people are viewed in particular ways, reacted to as “crazy,” and perhaps even encouraged to act sick, they gradually learn to accept and play the assigned social role. Ultimately the label seems appropriate.

A famous study called “On Being Sane in Insane Places” by clinical investigator David Rosenhan (1973) supports this position. Eight normal people, actually colleagues of Rosenhan, presented themselves at various mental hospitals, complaining that they had been hearing voices say the words “empty,” “hollow,” and “thud.” On the basis of this complaint alone, each was diagnosed as having schizophrenia and admitted.

Moreover, the pseudopatients had a hard time convincing others that they were well once they had been given the diagnostic label. Their hospitalizations ranged from 7 to 52 days, even though they behaved normally and stopped reporting symptoms as soon as they were admitted. In addition, the label “schizophrenia” kept influencing the way the staff viewed and dealt with them. For example, one pseudopatient who paced the corridor out of boredom was, in clinical notes, described as “nervous.” For their part, the pseudopatients came to feel powerless, invisible, and bored.

Social Connections and Supports Family-

Some clinical theorists believe that people who are unwilling or unable to communicate and develop relationships in their everyday lives will often find adequate social contacts online, using social networking sites like Facebook. Although this may be true for some such individuals, research suggests that people’s online relationships tend to parallel their offline relationships (Dolan, 2011). One survey of 172 college students, for example, found that those students with the most friends on Facebook also were particularly social offline, while those who were less willing to communicate with other people offline also tended to initiate far fewer relationships on Facebook (Sheldon, 2008).

66

family systems theory A theory that views the family as a system of interacting parts whose interactions exhibit consistent patterns and unstated rules.

Family Structure and Communication Of course, one of the important social networks for an individual is his or her family. According to family systems theory, the family is a system of interacting parts—

Family systems theory holds that certain family systems are particularly likely to produce abnormal functioning in individual members. Some families, for example, have an enmeshed structure in which the members are grossly overinvolved in one another’s activities, thoughts, and feelings. Children from this kind of family may have great difficulty becoming independent in life (Santiseban et al., 2001). Some families display disengagement, which is marked by very rigid boundaries between the members. Children from these families may find it hard to function in a group or to give or request support (Corey, 2012, 2004).

How might family theorists react to writer Leo Tolstoy’s famous claim that “every unhappy family is unhappy in its own fashion”?

Philip Berman’s angry and impulsive personal style might be seen as the product of a disturbed family structure. According to family systems theorists, the whole family—

Family systems theorists would also seek to clarify the precise nature of Philip’s relationship with each parent. Is he enmeshed with his mother and/or disengaged from his father? They would look too at the rules governing the sibling relationship in the family, the relationship between Philip’s parents and brother, and the nature of parent–

Family-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Being Social

Most people text faster when texting persons they like.

For most people, silence becomes awkward after about four seconds.

The maximum number of in-

(Pear, 2013)

67

The family-

group therapy A therapy format in which a group of people with similar problems meet together with a therapist to work on those problems.

Group Therapy Thousands of therapists specialize in group therapy, a format in which a therapist meets with a group of clients who have similar problems. One survey of clinical psychologists showed that almost one-

68

MindTech

Have Your Avatar Call My Avatar

The sociocultural model holds that abnormal behavior is best understood and treated in a social context. Thus, some proponents of this perspective are particularly interested in a relatively new feature in cybertherapy—

In another use of avatars, some real-

Clients know they are entering a make-

In one highly publicized case, for example, a woman with agoraphobia—

Why might group therapy actually be more helpful to some people with psychological problems than individual therapy would be?

Research suggests that group therapy is of help to many clients, often as helpful as individual therapy (Green et al., 2015). The group format also has been used for purposes that are educational rather than therapeutic, such as “consciousness raising” and spiritual inspiration.

self-

A format similar to group therapy is the self-

family therapy A therapy format in which the therapist meets with all members of a family and helps them to change in therapeutic ways.

Family Therapy Family therapy was first introduced in the 1950s. A therapist meets with all members of a family, points out problem behaviors and interactions, and helps the whole family to change its ways (Goldenberg et al., 2014). Here, the entire family is viewed as the unit under treatment, even if only one of the members receives a clinical diagnosis. The following is a typical interaction between family members and a therapist:

Tommy sat motionless in a chair gazing out the window. He was fourteen and a bit small for his age…. Sissy was eleven. She was sitting on the couch between her Mom and Dad with a smile on her face. Across from them sat Ms. Fargo, the family therapist.

Ms. Fargo spoke. “Could you be a little more specific about the changes you have seen in Tommy and when they came about?”

Mrs. Davis answered first. “Well, I guess it was about two years ago. Tommy started getting in fights at school. When we talked to him at home he said it was none of our business. He became moody and disobedient. He wouldn’t do anything that we wanted him to. He began to act mean to his sister and even hit her.”

69

“What about the fights at school?” Ms. Fargo asked.

This time it was Mr. Davis who spoke first. “Ginny was more worried about them than I was. I used to fight a lot when I was in school and I think it is normal…. But I was very respectful to my parents, especially my Dad. If I ever got out of line he would smack me one.”

“Have you ever had to hit Tommy?” Ms. Fargo inquired softly.

“Sure, a couple of times, but it didn’t seem to do any good.”

All at once Tommy seemed to be paying attention, his eyes riveted on his father. “Yeah, he hit me a lot, for no reason at all!”

“Now, that’s not true, Thomas.” Mrs. Davis has a scolding expression on her face. “If you behaved yourself a little better you wouldn’t get hit. Ms. Fargo, I can’t say that I am in favor of the hitting, but I understand sometimes how frustrating it may be for Bob.”

“You don’t know how frustrating it is for me, honey.” Bob seemed upset. “You don’t have to work all day at the office and then come home to contend with all of this. Sometimes I feel like I don’t even want to come home.”

Ginny gave him a hard stare. “You think things at home are easy all day? I could use some support from you. You think all you have to do is earn the money and I will do everything else. Well, I am not about to do that anymore.” … [She] began to cry. “I just don’t know what to do anymore. Things just seem so hopeless. Why can’t people be nice in this family anymore? I don’t think I am asking too much, am I?”

Ms. Fargo … looked at each person briefly and was sure to make eye contact. “There seems to be a lot going on …. I think we are going to need to understand a lot of things to see why this is happening.”

(Sheras & Worchel, 1979, pp. 108–

Family therapists may follow any of the major theoretical models, but many of them adopt the principles of family systems theory (Riina & McHale, 2014). Today 2 percent of all clinical psychologists, 5 percent of counseling psychologists, and 14 percent of social workers identify themselves mainly as family systems therapists (Prochaska & Norcross, 2013).

BETWEEN THE LINES

Shifting Family Values

| 59% | Percentage of adults who say their families have fewer family dinners than when they were growing up |

| 10 | Average number of weekly hours today’s fathers spend doing housework, compared with 4 hours a half- |

| 18 | Average number of weekly hours today’s mothers spend doing housework, compared with 32 hours a half- |

(Harris Interactive, 2013; Pew Research Center, 2013)

As you read earlier, family systems theory holds that each family has its own rules, structure, and communication patterns that shape the individual members’ behavior. In one family systems approach, structural family therapy, therapists try to change the family power structure, the roles each person plays, and the relationships between members (Goldenberg et al., 2014; Minuchin, 2007, 1987, 1974). In another, conjoint family therapy, therapists try to help members recognize and change harmful patterns of communication (Sharf, 2015; Satir, 1987, 1967, 1964).

Family therapies of various kinds are often helpful to individuals, although research has not yet clarified how helpful (Goldenberg et al., 2014; Nichols, 2013). Some studies have found that as many as 65 percent of individuals treated with family approaches improve, while other studies suggest much lower success rates. Nor has any one type of family therapy emerged as consistently more helpful than the others (Bitter, 2013; Alexander et al., 2002).

couple therapy A therapy format in which the therapist works with two people who share a long-

Couple Therapy In couple therapy, or marital therapy, the therapist works with two individuals who are in a long-

70

Although some degree of conflict exists in any long-

Couple therapy, like family and group therapy, may follow the principles of any of the major therapy orientations. Cognitive-

Couples treated by couple therapy seem to show greater improvement in their relationships than couples with similar problems who do not receive treatment, but no one form of couple therapy stands out as superior to others (Christensen et al., 2014, 2010). Although marital functioning improved in two-

community mental health treatment A treatment approach that emphasizes community care.

Community Treatment Community mental health treatment programs allow clients to receive treatment in nearby social surroundings as they try to recover. Such community-

As you read in Chapter 1, a key principle of community treatment is prevention. This involves clinicians actively reaching out to clients rather than waiting for them to seek treatment. Research suggests that such efforts are often very successful (Urben et al., 2015; Beardslee et al., 2013) Community workers recognize three types of prevention, which they call primary, secondary, and tertiary.

Primary prevention consists of efforts to improve community attitudes and policies. Its goal is to prevent psychological disorders altogether. Community workers may, for example, consult with a local school board, offer public workshops on stress reduction, or construct Web sites on how to cope effectively.

Secondary prevention consists of identifying and treating psychological disorders in the early stages, before they become serious. Community workers may work with teachers, ministers, or police to help them recognize the early signs of psychological dysfunction and teach them how to help people find treatment. Similarly, hundreds of mental health Web sites provide this same kind of information to family members, teachers, and the like.

The goal of tertiary prevention is to provide effective treatment as soon as it is needed so that moderate or severe disorders do not become long-

How Do Multicultural Theorists Explain Abnormal Functioning?

71

BETWEEN THE LINES

Gender Bias in the Workplace

Women today earn $0.79 for every $1 earned by a man.

Around 60 percent of young adult women believe that women have to outperform men at work to get the same rewards; 48 percent of young adult men agree.

(Pew Research, 2013, 2010; Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2011; Yin, 2002)

Culture refers to the set of values, attitudes, beliefs, history, and behaviors shared by a group of people and communicated from one generation to the next (Matsumoto & Hwang, 2012, 2011; Matsumoto, 2007, 2001). We are, without question, a society of multiple cultures. Indeed, by the year 2050, the number of racial and ethnic minority group members in the United States will collectively equal or surpass the number of white Americans (U.S. Census Bureau, 2014; Kaiser Family Foundation, 2010).

multicultural perspective The view that each culture within a larger society has a particular set of values and beliefs, as well as special external pressures, that help account for the behavior and functioning of its members. Also called culturally diverse perspective.

Partly in response to this growing diversity, the multicultural, or culturally diverse, perspective has emerged (Leong, 2014, 2013). Multicultural psychologists seek to understand how culture, race, ethnicity, gender, and similar factors affect behavior and thought and how people of different cultures, races, and genders differ psychologically (Alegría et al., 2014, 2012, 2007). Today’s multicultural view is different from past—

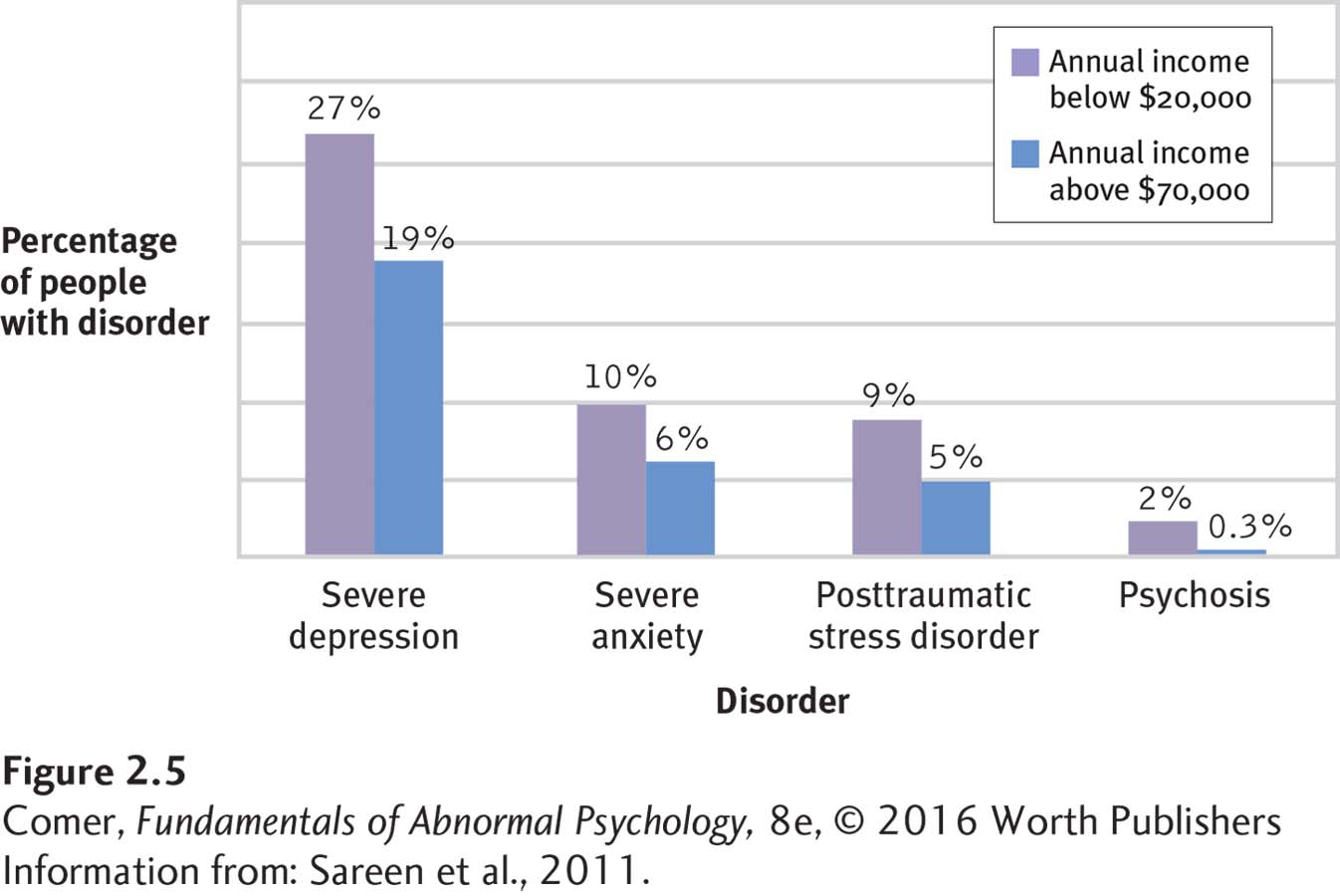

The groups in the United States that have received the most attention from multicultural researchers are ethnic and racial minority groups (African American, Hispanic American, American Indian, and Asian American groups) and groups such as economically disadvantaged persons, gays and lesbians, and women (although women are not technically a minority group). Each of these groups is subjected to special pressures in American society that may contribute to feelings of stress and, in some cases, to abnormal functioning. Researchers have learned, for example, that psychological abnormality, especially severe psychological abnormality, is indeed more common among poorer people than among wealthier people (Wittayanukorn, 2013; Sareen et al., 2011) (see Figure 2.5). Perhaps the pressures of poverty explain this relationship.

Of course, membership in these various groups overlaps. Many members of minority groups, for example, also live in poverty. The higher rates of crime, unemployment, overcrowding, and homelessness; the inferior medical care; and the limited educational opportunities typically available to poor people may place great stress on many members of such minority groups (Alegria et al., 2014; Miller et al., 2011).

Multicultural researchers have also noted that the prejudice and discrimination faced by many minority groups may contribute to various forms of abnormal functioning (McDonald et al., 2014; Guimón, 2010). Women in Western society receive diagnoses of anxiety disorders and of depression at least twice as often as men (NIMH, 2015). Similarly, African Americans, Hispanic Americans, and American Indians are more likely than white Americans to experience serious psychological distress or extreme sadness. American Indians also have exceptionally high alcoholism and suicide rates (Maza, 2015; Horwitz, 2014). Although many factors may combine to produce these differences, prejudice based on race and sexual orientation, and the problems such prejudice poses, may contribute to abnormal patterns of tension, unhappiness, low self-

Multicultural Treatments

72

Studies conducted throughout the world have found that members of ethnic and racial minority groups tend to show less improvement in clinical treatment, make less use of mental health services, and stop therapy sooner than members of majority groups (Cook et al., 2014; Comas-

culture-

gender-

A number of studies suggest that two features of treatment can increase a therapist’s effectiveness with minority clients: (1) greater sensitivity to cultural issues and (2) inclusion of cultural morals and models in treatment, especially in therapies for children and adolescents (Comas-

Culture-

Special cultural instruction for therapists in their graduate training program

The therapist’s awareness of a client’s cultural values

The therapist’s awareness of the stress, prejudices, and stereotypes to which minority clients are exposed

The therapist’s awareness of the hardships faced by the children of immigrants

Helping clients recognize the impact of both their own culture and the dominant culture on their self-

views and behaviors Helping clients identify and express suppressed anger and pain

Helping clients achieve a bicultural balance that feels right for them

Helping clients raise their self-

esteem— a sense of self- worth that has often been damaged by generations of negative messages

Assessing the Sociocultural Model

The family-

BETWEEN THE LINES

Who Is Discriminated Against?

| 35% | Percentage of African Americans who report being treated unfairly because of their race in the past year |

| 20% | Percentage of Hispanic Americans who report being treated unfairly because of their race in the past year |

| 10% | Percentage of white Americans who report being treated unfairly because of their race in the past year |

(Pew Research Center, 2013)

At the same time, the sociocultural model has certain problems. To begin with, sociocultural research findings are often difficult to interpret. Indeed, research may reveal a relationship between certain family or cultural factors and a particular disorder yet fail to establish that they are its cause. Studies show a link between family conflict and schizophrenia, for example, but that finding does not necessarily mean that family dysfunction causes schizophrenia. It is equally possible that family functioning is disrupted by the tension and conflict created by the psychotic behavior of a family member.

Another limitation of the sociocultural model is its inability to predict abnormality in specific individuals. If, for example, social conditions such as prejudice and discrimination are key causes of anxiety and depression, why do only some of the people subjected to such forces experience psychological disorders? Are still other factors necessary for the development of the disorders?

Given these limitations, most clinicians view the family-

73

Summing Up

THE SOCIOCULTURAL MODEL One sociocultural perspective, the family-

The multicultural perspective, another perspective from the sociocultural model, holds that an individual’s behavior, whether normal or abnormal, is best understood when examined in the light of his or her unique cultural context, including the values of that culture and the special external pressures faced by members of that culture. Practitioners of this perspective may practice culture-