14.4 Oppositional Defiant Disorder and Conduct Disorder

473

oppositional defiant disorder A disorder in which children are persistently argumentative, defiant, angry, irritable, and perhaps vindictive.

Most children break rules or misbehave on occasion. If they consistently display extreme hostility and defiance, however, they may qualify for a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. Those with oppositional defiant disorder are persistently argumentative or defiant, angry or irritable, and, in some cases, vindictive (APA, 2013). They may argue repeatedly with adults, ignore adult rules and requests, deliberately annoy other people, and feel much anger and resentment. As many as 10 percent of children qualify for a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder (Mash & Wolfe, 2015; Wilkes & Nixon, 2015). The disorder is more common in boys than in girls before puberty but equal in both sexes after puberty.

conduct disorder A disorder in which a child repeatedly violates the basic rights of others and displays significant aggression.

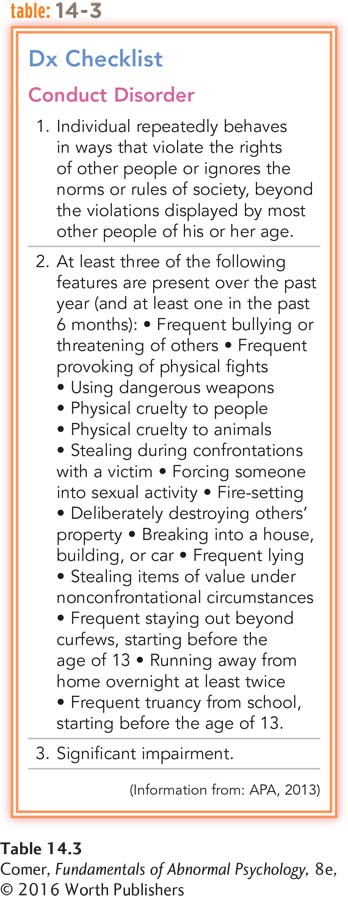

Children with conduct disorder, a more severe problem, repeatedly violate the basic rights of others (APA, 2013). They are often aggressive and may be physically cruel to people or animals, deliberately destroy other people’s property, skip school, steal, or run away from home (see Table 14.3). Many threaten or harm their victims, committing such crimes as firesetting, shoplifting, forgery, breaking into buildings or cars, mugging, and armed robbery. As they get older, their acts of physical violence may include rape or, in rare cases, homicide. The symptoms of conduct disorder are apparent in this summary of a clinical interview with a 15-

Questioning revealed that Derek was getting into ….erious trouble of late, having been arrested for shoplifting 4 weeks before. Derek was caught with one other youth when he and a dozen friends swarmed a convenience store and took everything they could before leaving in cars. This event followed similar others at [an electronics] store and a ….lothing store. Derek blamed his friends for his arrest because they apparently left him behind as he straggled out of the store. He was charged only with shoplifting, however, after police found him holding just three candy bars and a bag of potato chips. Derek expressed no remorse for the theft or any care for the store clerk who was injured when one of the teens pushed her into a glass case. When informed of the clerk’s injury, for example, Derek replied, “I didn’t do it, so what do I care?”

The psychologist questioned Derek further about other legal violations and discovered a rather extended history of trouble. Derek was arrested for vandalism 10 months earlier for breaking windows and damaging cars on school property. He received probation for 6 months because this was his first offense. Derek also boasted of other exploits for which he was not caught, including several shoplifting episodes, ….oyriding, and missing school. Derek missed 23 days (50 percent) of school since the beginning of the academic year. In addition, he described break-

(Kearney, 2013, pp. 87–

Conduct disorder usually begins between 7 and 15 years of age (APA, 2013). As many as 10 percent of children, three-

474

Some clinical theorists believe that there are actually several kinds of conduct disorder, including (1) the overt-

Other researchers distinguish yet another pattern of aggression found in certain cases of conduct disorder, relational aggression, in which the individual is socially isolated and primarily engages in social misdeeds such as slandering others, spreading rumors, and manipulating friendships (Ostrov et al., 2014). Relational aggression is more common among girls than boys.

Many children with conduct disorder are suspended from school, placed in foster homes, or incarcerated (Weyandt et al., 2011). When children between the ages of 8 and 18 break the law, the legal system often labels them juvenile delinquents (Wiklund et al., 2014; Jiron, 2010). Boys are much more involved in juvenile crime than girls, although the gap between them is narrowing. After steadily rising during the 1990s, the number of arrests of teenagers for serious crimes has fallen by one-

What Are the Causes of Conduct Disorder?

Many cases of conduct disorder, particularly those marked by destructive behaviors, have been linked to genetic and biological factors (Kerekes et al., 2014; Wallace et al., 2014). In addition, a number of cases have been tied to drug abuse, poverty, traumatic events, and exposure to violent peers or community violence (Wymbs et al., 2014; Weyandt et al., 2011). Most often, conduct disorder has been tied to troubled parent–

How Do Clinicians Treat Conduct Disorder?

BETWEEN THE LINES

Narrowing the Gender Gap

One of every three teens arrested for violent crimes is female.

(Department of Justice, 2008; Scelfo, 2005)

Because aggressive behaviors become more locked in with age, treatments for conduct disorder are generally most effective with children younger than 13 (APA, 2013). A number of interventions, from sociocultural to child-

Sociocultural Treatments Given the importance of family factors in conduct disorder, therapists often use family interventions. One such approach, used with preschoolers, is called parent–

475

BETWEEN THE LINES

Underlying Problems

There are approximately 110,000 teenagers in the United States incarcerated each year. Three-

(Nordal, 2010)

When children reach school age, therapists often use a family intervention called parent management training. In this approach, (1) parents are again taught more effective ways to deal with their children, and (2) parents and children meet together in behavior-

Other sociocultural approaches, such as residential treatment in the community and programs at school, have also helped some children improve. In one such approach, treatment foster care, delinquent boys and girls with conduct disorder are assigned to a foster home in the community by the juvenile justice system (Henggeler & Sheidow, 2012). While there, the children, foster parents, and birth parents all receive training and treatment, followed by more treatment and support for the children and their biological parents after the children leave foster care.

How might juvenile training centers themselves contribute to the high recidivism rate among teenage criminal offenders?

In contrast to these sociocultural interventions, institutionalization in so-

Child-

In another child-

Studies indicate that child-

Prevention It may be that the best hope for dealing with the problem of conduct disorder lies in prevention programs that begin in the earliest stages of childhood (Hektner et al., 2014). These programs try to change unfavorable social conditions before a conduct disorder is able to develop. The programs may offer training opportunities for young people, recreational facilities, and health care and may try to ease the stresses of poverty and improve parents’ child-