Free Speech and Media Bias

Free Speech and Media Bias

Page 392

The infamous 2004 Super Bowl halftime show featured a moment that entered the cultural lexicon as a “wardrobe malfunction” when performer justin Timberlake pulled off a cover, exposing Janet Jackson’s breast. CBS stations around the country faced major fines for indecency, as well as an extended series of court battles over those fines. The debate over whether the government has the right to fine networks or censor objectionable messages is rooted in competing interpretations of constitutional law.

The First Amendment. The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution states, “Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.” The principle here is that news media and individual citizens of a well-functioning republic need to be free to criticize their government and speak their views. This means that, even when speech is offensive, the government cannot ban it, punish it, or restrict it, except under very rare circumstances. Interestingly, this doesn’t mean that the U.S. government hasn’t tried to exercise control over media content. But its attempts at regulation are often struck down by the courts as unconstitutional (such as bans on pornography and heavy regulation of political campaign speech). The regulations that U.S. courts allow mostly involve rules about technical issues, such as broadcast signals or ownership of stations and copyright laws. In effect, the U.S. government actually has little direct influence on media content compared to the governments of other countries.

Do all American media benefit from this protection? The courts have generally held that creative expression is protected speech, whether in print, on TV, in movies, or on the Internet. However, the courts have also upheld some content regulations for some kinds of media, particularly broadcasting, as we’ll see in the next section.

Electronic Media Regulation. There is an important legal difference between broadcast signals and cable or satellite channels. Broadcasting refers to signals carried over the airwaves from a station transmitter to a receiver. For radio, these are the AM/FM stations you might listen to in your car. For television, they are the major networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, FOX, and The CW) and independent local stations. Most cable and satellite companies now carry these signals to you, so the broadcast TV channels today look just like every other channel on TV.

However, because broadcasting frequencies are limited and because the airwaves themselves are essentially a public resource, the government—through the Federal Communications Commission (FCC)—can regulate which private companies may broadcast over them. In order to keep their broadcasting licenses, broadcasters must agree to serve the public interest. Cable and satellite providers, on the other hand, do not use publicly owned resources to deliver their signals, so they have not been subject to the same kinds of regulations.

While the First Amendment right to free speech and press do apply to broadcasters, broadcast television networks and radio stations are subject to some speech restrictions. The courts have held that the government can impose restrictions that serve a “compelling government interest” (that is, the government has a really good reason for doing it, such as to protect children) and only when the regulation is the “least restrictive” way to serve that interest (that is, the government cannot ban all adult TV content just to protect kids from seeing it) (Action for Children’s Television v. FCC, 1991).

Recall the Janet Jackson Super Bowl incident discussed earlier. CBS stations were fined because the FCC said that the dance number violated a ban on broadcast indecency. Indecency legally means “patently offensive . . . sexual or excretory activities or organs” (FCC v. Pacifica Foundation, 1978), but in practice it means talking about or showing sexual or other bodily functions in a very lewd or vulgar way. This is a very subjective evaluation, of course, which is why broadcasters frequently end up fighting over their fines in court.

The Supreme Court has upheld the government’s expressed interest in protecting children from indecent content (FCC v. Pacifica Foundation, 1978). However, the courts have also said that the ban must be limited only to specific times of day (such as 6 A.M. to 10 P.M.) when children are likely to be in the audience (Action for Children’s Television v. FCC, 1995). Remember that this ban does not apply to cable and satellite channels—so MTV and Comedy Central, for example, may choose to air nudity or use bad language at any time, based solely on their sense of what their audiences will tolerate.

Although indecency rules are what you may hear most about, there are also other important areas of media regulation. Much FCC action is directed at how the media corporations conduct their business, such as approving or denying mergers. The FCC has also recently expanded its influence over the Internet, including controversial attempts to limit the control that Internet service providers have over the online traffic that flows through their services.

Media Bias. As you’ll recall from chapter 1 and chapter 2, our own thoughts, opinions, and experiences influence the messages we send as well as the way we interpret the messages we receive. These communication biases are also at work when it comes to mass media. Most scholars agree that media sources—both news and entertainment—express some degree of bias in their viewpoints and in their content. News coverage of the Tea Party movement, for example, can be quite different, depending on the political leanings of the network or news organization doing the reporting as well as the personal ideologies of individual reporters, editors, and producers.

THINGS TO TRY

Compare the news coverage for a political controversy on the Web sites of Fox News, CNN, MSNBC, NPR, and the wire services (AP and Reuters). What are the similarities? What are the differences? Then check the Web sites for both Media Matters for America and Media Research Center (or its offshoot, NewsBusters), and see how each of these media watchdogs criticizes the coverage. Do these watchdogs themselves seem to hold biases too?

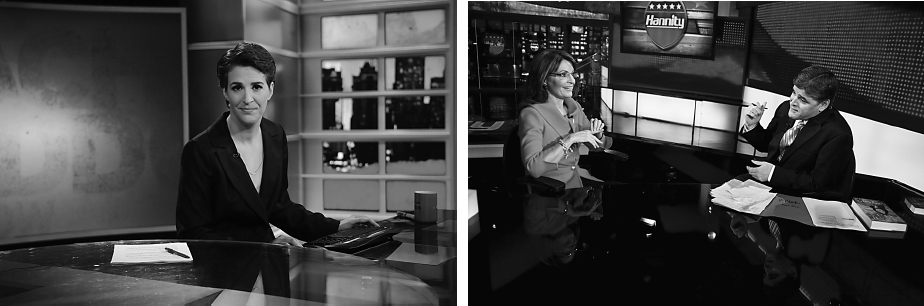

The trend toward more partisan news has increased since the 1990s (Coe et al., 2008; Iyengar & Hahn, 2009). In the latter half of the twentieth century, news organizations across the entire mass media generally expressed commitment to the goal of objectivity—that is, they were primarily concerned with facts and uninfluenced by personal or political bias, prejudice, or interpretation. Although traditionally embraced as a laudable goal, both consumers and journalists over the years have questioned whether this goal has been (or even can be) met (Duffy, Thorson, & Vultee, 2009; Figdor, 2010). Today’s media, in any case, appear more willing to embrace the economic advantages of partisanship, as cable news networks in particular tend to narrowcast to one viewpoint or another in search of higher ratings. The Internet also supports a wide range of political news and analysis, from the Breitbart series of Web sites on the right to the Huffington Post on the left, not to mention the “blogosphere” of individual writers and commentators online. Thus the variety of ideologies represented by mass media today makes it difficult to pin any particular bias on “mainstream” media as a whole.

That does not mean, however, that bias is unimportant. Studies suggest that when presented with coverage of any given issue, strong partisans of both parties, especially those who discuss media bias with like-minded partisans, perceive the news to be biased against their own side (Eveland & Shah, 2003). In a nutshell, that means we tend to see those we agree with as less biased than those we disagree with.

Critics on the right and the left agree that bias in the media is also a function of the economics and constraints of the news-gathering process itself (Farnsworth & Lichter, 2010). The 24/7 news cycle with multiple technological outlets to fill may lead to overreliance on easy sources—particularly spokespersons for government or interest groups. The focus on breaking news rather than ongoing issues may lead to a lack of depth, and the need to frame issues in ways that increase drama encourages coverage of politics as a horse race between conflicting parties rather than as the complex process that it is.

LearningCurve

bedfordstmartins.com/commandyou