Evaluating Supporting Material

Evaluating Supporting Material

Page 249

Once you’ve gathered a variety of sources, you must critically evaluate the material and determine which sources to use. After all, your credibility as a speaker largely depends on the accuracy and credibility of your sources, as well as their appropriateness for your topic and your audience.

Credible Sources. In today’s media, anyone can put up a blog or a Web page, edit a wiki, or post a video to YouTube. What’s more, a large and growing number of opinion-based publications, broadcasting networks, and Web sites provide an outlet for research that is heavily biased. Consequently, it is always worth spending a little time evaluating credibility—the quality, authority, and reliability—of each source you use. One simple way to approach this is to evaluate the author’s credentials. This means that you should note if the author is a medical doctor, a Ph.D., an attorney, a CPA, or another licensed professional and whether he or she is affiliated with a reputable organization or institution. For example, if you are seeking statistics on the health effects of cigarette smoke, an article written by an M.D. affiliated with the American Lung Association would be more credible than an editorial written by your classmate.

In print and online, a reliable source may show a trail of research by supplying details about where the information came from, such as a thorough list of references. In news writing, source information is integrated into the text. A newspaper or magazine article, for example, will credit information to named sources (“Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig said . . .”) or credentialed but unnamed sources (“One high-ranking State Department official said, on condition of anonymity . . .”).

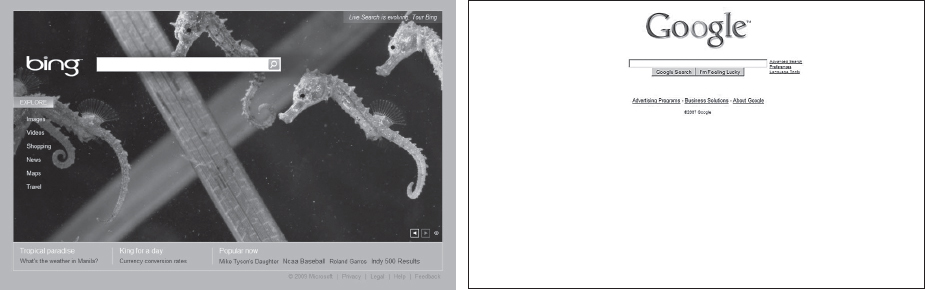

The Internet poses special problems when it comes to credibility owing to the ease with which material can be posted online. Check for balanced, impartial information that is not biased, and note the background or credentials of the authors. If references are listed, verify them to confirm their authenticity. Web sites can be quickly assessed for reliability by looking at the domain, or the suffix of the Web site address. Credible Web sites often end with .edu (educational institution), .mil (military site), or .gov (government).

Technology and You

Have you ever run into credibility problems with sources you’ve found on the Internet? What was the situation, and how did you verify (or refute) their authenticity?

Up-to-Date Sources. In most cases, you’ll want to use the most recent information available to keep your speech timely and relevant. Isaiah, for example, is speaking to a group of potential clients about his company’s graphic design services. If, during his speech, he makes reference to testimonials from satisfied clients in 2008 and earlier, the audience may wonder if the company has gone downhill since then. For this reason, always determine when your source was written or last updated; sources without dates may indicate that the information is not as timely or relevant as it could be.

To be compelling, your supporting material should also be vivid. Vivid material is clear and vibrant, never vague. For example, in a speech about the 2004 cicada invasion of the Washington, D.C., area, Ana might reference a source describing these bugs as large insects, about one and a half inches long, with red eyes, black bodies, and fragile wings; she might also use a direct quotation from a D.C. resident who noted that “there were so many cicadas that the ground, trees, and streets looked like they were covered by an oil slick.” Such vivid (and gross) descriptions of information interest listeners. Look for clear, concrete supporting details that encourage the audience to form visual representations of the object or event you are describing.

THINGS TO TRY

Tune in to a few news pundits—for example, Bill O’Reilly, Rachel Maddow, Randi Rhodes, or Rush Limbaugh—on the radio or on television. Listen carefully to what they say, and consider how they back up their statements. Do they provide source material as they speak? Can you link to their sources from their online blogs? How does the way they back up their points or fail to back them up influence your perceptions of what they say?

Accurate Sources. When compiling support for your speech, it is important to find accurate sources—sources that are true, correct, and exact. A speaker who presents inaccurate information may very well lose the respect and attention of the audience. There are several ways to help ensure that you are studying accurate sources. In addition to being credible and up-to-date, accurate sources are exact—meaning they offer detailed and precise information. A source that notes that more than 33,000 people died as a result of automobile accidents in the United States last year is less accurate than a source that notes that 33,808 people died in such accidents. The more precise your sources, the more credibility you will gain with your audience.

Compelling Sources. Support material that is strong, interesting, and believable is considered compelling information. This kind of information helps your audience understand, process, and retain your message. A speaker might note that 65 percent of adults were sending and receiving texts in September 2009 and that 72 percent were texting in May 2010. However, adults do not send nearly the number of texts per day as teenagers (twelve- to seventeen-year-olds), who send and receive, on average, five times more (Lenhart, 2010). Now those are some compelling statistics!

LearningCurve

bedfordstmartins.com/commandyou