Effective Visual Delivery

Effective Visual Delivery

Page 295

In the same way that a monotone can lull an audience to sleep, so can a stale, dull physical presence. This doesn’t mean that you need to be doing cartwheels throughout your speech, but it does mean that you should avoid keeping your hands glued to the podium and that you should look up from your note cards once in a while. Otherwise, you’ll be little more than a talking head, and your audience will quickly lose interest. What’s more, effective visual cues can enhance a presentation, helping you clarify and emphasize your points in an interesting and compelling way.

Dressing for the Occasion. If you’re like most people, you probably hop out of bed in the morning, open your closet, and hope that you have something decent and clean to wear to work or class. However, on the day of your speech—just like the day of a job interview or an important date—you don’t want to leave your appearance to chance.

On that day you are a speaker, and even though you may be presenting to a group of friends or classmates you see every week, it is imperative that you look the part of someone capable of informing or persuading the audience. While you certainly don’t need to have a Hollywood-perfect body, an expensive wardrobe, or a killer hairstyle to inform or persuade anyone, you should attempt to look and feel your personal best. You can signal authority and enhance your credibility by dressing professionally in neat, ironed clothing—like a pair of black pants or a skirt, with a button-down shirt or simple sweater (Cialdini, 2008; Pratkanis & Aronson, 2001). You should certainly avoid looking overly casual (by wearing shorts, cut-off jeans, or sneakers), which can signal that you don’t take the audience, your speech topic, or even yourself as a speaker seriously.

Using Effective Eye Behavior. As we noted in chapter 5, eye behavior is a crucial aspect of nonverbal communication that can be both effective and appropriate when you consider the cultural context in which you are communicating. In Vietnamese culture, for example, it is considered inappropriate and rude to make prolonged, direct eye contact with someone, particularly if that person is of a higher rank or social status. In the culture of the United States and of many other Western countries, conversely, a lack of eye contact can make a speaker seem suspicious or untrustworthy, making direct eye contact one of the most important nonverbal actions in public speaking, signaling respect for and interest in the audience (Axtell, 1991). But how can a speaker make and maintain eye contact with a large group of individuals?

One way is to move your eyes from one person to another (in a small group) or one section of people to another (in a large group), a technique called scanning. Scanning allows you to make brief eye contact with almost everyone in an audience, no matter how large. To use it, picture yourself standing in front of the audience, and then divide the room into four imaginary sections. As you move from idea to idea in your speech, move your eye contact into a new section. Select a friendly-looking person in the quadrant, and focus your eye contact directly on that person while completing the idea (just make sure you don’t pick a friend who will try to make you laugh!). Then change quadrants, and select a person from the new group. Tips for using the scanning technique are offered in Table 13.1.

| Table 13.1 Tips for Scanning Your Audience | |

| Work in sections and avoid the “lighthouse” effect | Do not scan from left to right or right to left. Always work in sections and move randomly from one section to another. If you simply rotate from left to right, looking at no one in particular, you may look like a human lighthouse! |

| Look people in the eye | Avoid looking at people’s foreheads or over their heads; look them in the eye, even if they are not looking back at you. |

| Focus for a moment | Remember to pause long enough on an individual so that the person can recognize that you are looking directly at him or her. |

| Don’t jump away | If someone is not looking at you, stay with the person anyway until you’ve finished your thought. Then move on to another. |

| Divide large groups | If the audience is too large for you to get to everyone, look at small groups of two or three people sitting together. |

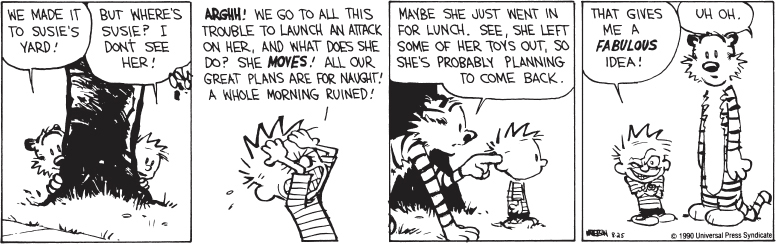

Incorporating Facial Expressions and Gestures. Have you ever seen a cartoon in which a character’s face contorts, the jaw dropping to the floor or the eyes becoming small white dots? The animator certainly gets the point across—this character is either entirely surprised or seriously confused. Your facial expressions, while not as exaggerated as those of a cartoon character, serve a similar purpose: they let your audience know when your words arouse fear, anger, happiness, joy, frustration, or other emotions. The critical factor is that your expressions must match the verbal message that you are sending in your speech. As a competent communicator, you are unlikely to smile when delivering a eulogy—unless you are recounting a particularly funny or endearing memory about the deceased.

THINGS TO TRY

Search YouTube for a segment with a speaker giving a speech (the topic does not matter). Turn off the volume so you can only see (not hear) the speech. Analyze the physical speech delivery of the speaker. Make lists of the problems with his or her speech delivery and of the things the speaker does well (for example, maintains eye contact). Then watch the speech again, this time with the volume on. Listen carefully to the vocal delivery (such as pitch, rate, and volume) of the speaker. What do you notice about his or her voice? Compare your lists, and note all your observations as you prepare for your own speech.

Like facial expressions, gestures amplify the meaning of your speech. Clenching your fist, counting with your fingers, and spreading your hands far apart to indicate distance or size all reinforce or clarify your message.

Like facial expressions, gestures amplify the meaning of your speech. Clenching your fist, counting with your fingers, and spreading your hands far apart to indicate distance or size all reinforce or clarify your message. What is most important is that your gestures are appropriate and natural. So if you want to show emotion but you feel awkward putting your hand over your heart, don’t do it; your audience will be able to tell that you feel uncomfortable.

Controlling Body Movements. In addition to eye behavior, facial expressions, and gestures, your audience can’t help but notice your body. In most speaking situations you encounter, the best way to highlight your speech content is to restrict your body movements so that the audience can focus on your words. Consider, for example, your posture, or the position of your arms and legs and how you carry your body. Generally, when a speaker slumps forward or leans on a podium, rocks back and forth, or paces forward and backward, the audience perceives the speaker as unpolished, and listeners’ attention shifts from the message to the speaker’s body movements.

How do you prevent such movements from happening, particularly if you’re someone who fidgets when nervous? One useful technique is called planting. Stand with your legs apart at a distance that is equal to your shoulders. Bend your knees slightly so that they do not lock. From this position, you are able to gesture freely, and when you are ready to move, you can take a few steps, replant, and continue speaking. The key is to plant following every movement that you make.