The Competent Communication Model

The Competent Communication Model

Page 19

Though the linear and interaction models help illustrate the communication process, neither captures the complex process of competent communication that we talked about in the preceding section (Wiemann & Backlund, 1980).

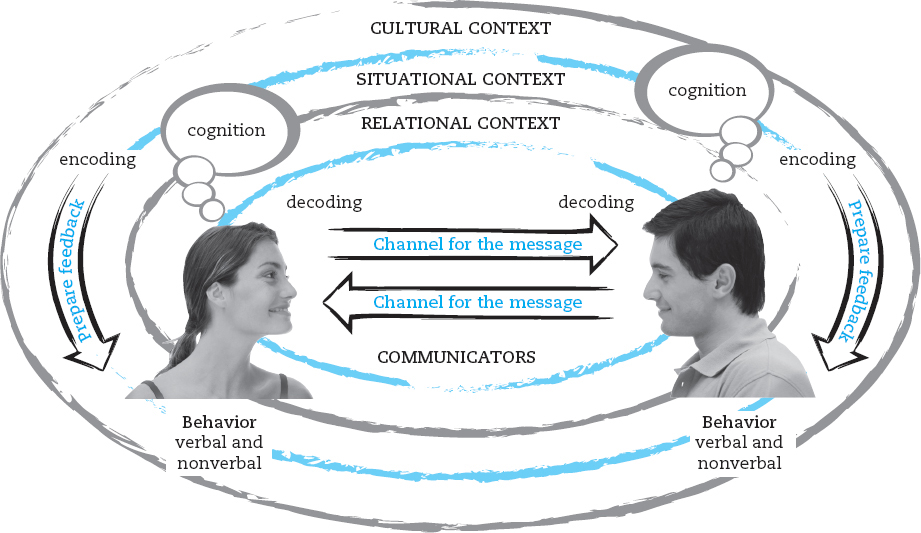

To illustrate this complex process, we developed a model of communication that shows effective and appropriate communication (see Figure 1.3). This competent communication model is transactional: the individuals (or groups or organizations) communicate simultaneously, sending and receiving messages (verbally and nonverbally) at the same moment—and all this takes place within three contexts: relational, situational, and cultural.2

In this model, arrows show the links between communication behaviors by representing messages being sent and received. In face-to-face communication, the behaviors of both communicators influence each individual at the same time. For example, Cliff smiles and nods at Jalissa without saying anything as Jalissa talks about the meeting she hosted for her book club. Through these behaviors, Cliff is sending messages of encouragement while receiving her verbal messages. Jalissa is sending all sorts of messages about the book she chose for that week’s discussion, as well as the foods she selected and the way she prepared for the get-together. But she is also receiving messages from Cliff that she interprets as positive interest. Both Cliff and Jalissa are simultaneously encoding (sending) and simultaneously decoding (receiving) communication behavior.

This transaction changes slightly with different types of communication. For example, in a mediated form of communication—a Facebook wall posting or texting, for example—the sending and receiving of messages may not be simultaneous. In such cases, the communicators are more likely to take turns or time may elapse between messages. In mass media such as TV or radio, feedback may be even more limited and delayed—audience reactions to a TV show are typically gauged only by Nielsen ratings (how many people watched) or by comments posted by fans on blogs or Twitter.

The competent communication model takes into account not only the transactional nature of communication but also the role of communicators themselves—their internal thoughts and influences as well as the various contexts in which they operate. There are four main spheres of influence at play in the competent communication model:

- The communicators. Two individuals are shown in Figure 1.3, but many variations are possible: an individual speaking to a live audience, multiple individuals in a group communicating, and so on.

- The relationships among the communicators.

- The situation in which the communication occurs.

- The cultural setting that frames the interaction.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these influences.

The Communicators. The most obvious elements in any communication are the communicators themselves. When sending and receiving messages, each communicator is influenced by cognitions, the thoughts they have about themselves and others, including their understanding and awareness of who they are (smart, funny, compassionate, and so on), how well they like who they are, and how successful they think they are. We discuss this process in much more depth in chapter 2. But for now, understand that your cognitions influence your behavior when you communicate. Behavior is observable communication, including verbal messages (the words you use) and nonverbal messages (facial expressions, body movements, clothing, gestures). So your cognitions inform your behavior—the messages you encode and send—which are then received and decoded by your communication partner. Your partner’s own cognitions influence how he or she interprets the message, prepares feedback, and encodes a new verbal or nonverbal message that is sent to you.

Ethics and You

Recall a communication situation in which you felt uncomfortable. What were your thoughts (cognitions) about yourself? About your partner? What could you say or do to clarify the situation?

This constant cycle can be seen in the following example. Devon knows that he’s a good student, but he struggles with math, chemistry, and physics. This embarrasses him because his mother is a doctor and his brother is an engineer. He rarely feels like he will succeed in these areas. He tells his friend Kayla that he can’t figure out why he failed his recent physics test since he studied for days beforehand. When he says this, his eyes are downcast and he looks angry. Kayla likes to think that she’s a good listener and prides herself on the fact that she rarely responds emotionally to delicate situations. She receives and decodes Devon’s message, prepares feedback, and encodes and sends a message of her own: she calmly asks whether Devon contacted his physics professor or an academic tutor for extra help. Devon receives and decodes Kayla’s message in light of his own cognitions about being a poor science student and feeling like he’s always struggling with physics. He notices that Kayla made very direct eye contact, that she didn’t smile, and that her message didn’t include any words of sympathy. He concludes that she is accusing him of not working hard enough. He prepares feedback and sends another message—his eyes are large and his arms are crossed and he loudly and sarcastically states, “Right, yeah, I guess I was just too dumb to think about that.”

Because communication situations have so many “moving parts,” they can vary greatly. Moreover, successful communicators usually have a high degree of cognitive complexity. That is, they can consider multiple scenarios, formulate multiple theories, and make multiple interpretations when encoding and decoding messages. In this case, Kayla might have considered that Devon really just needed some friendly reassurance rather than advice; Devon might have realized that Kayla was just trying to offer a helpful suggestion.

Relationships Among the Communicators. All communication, from mundane business transactions to intimate discussions, occurs within the context of the relationship you have with the person or persons with whom you are interacting. This relational context is represented by the inner sphere in the competent communication model. A kiss, for example, has a different meaning when bestowed on your mother than it does when shared with your spouse or romantic partner. When you make a new acquaintance, saying “Let’s be friends” can be an exciting invitation to get to know someone new, but the same message shared with someone you’ve been dating for a year shuts down intimacy. The relationship itself is influenced by its past history as well as both parties’ expectations for the current situation and for the future.

A relational history is the sum of the shared experiences of the individuals involved in the relationship. References to this common history (such as inside jokes) can be important in defining a relationship, both for the participants and for the participants’ associates. That’s because such references indicate to you, your partner, and others that there is something special about this relationship. Your relational history may also affect what is appropriate in a particular circumstance. For example, you may give advice to a sibling or close friend without worrying about politeness, but you might be more hesitant or more indirect with an acquaintance you haven’t known for very long. Relational history can complicate matters when you’re communicating on social-networking sites like Facebook. Your “friends” probably include those who are currently very close to you as well as those who are distant (for example, former high school classmates). Even if you direct your message to one friend in particular, all your friends can see it, so you might be letting those in distant relationships in on a private joke (or be making them feel left out).

Our communication is also shaped by our expectations and goals for the relationship. Expectations and goals can be quite different. For example, high school sweethearts may want their relationship to continue (a goal) but at the same time anticipate that going to college in different states could lead to a breakup (an expectation). With expectations and goals in mind, you formulate your behavior in the current conversation, and you interpret what your partner says in light of these same considerations. Clearly, our expectations and goals differ according to each relationship. They can and do change during the course of conversations, and they certainly change over the life span of a relationship.

The Situation. The situational context (represented by the middle sphere in the competent communication model) includes the social environment (a loud, boisterous party versus an intimate dinner for two), the physical place (at home in the kitchen versus at Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport), specific events and situations (a wedding versus a funeral), and even a specific mediated place (a private message versus a Facebook status update). Situation also includes where you live and work, your home or office decorations, the time of day or night, and the current events in the particular environment at the time.

For example, if Kevin gets home from work and asks Rhiannon what’s for dinner and Rhiannon shrieks, Kevin might conclude that she is mad at him. But if he considers the situational context, he might reinterpret her response. Looking around, he might see that his wife is still in her suit, meaning that she only just got home from a long day at work. He might notice that the kitchen sink is clogged, the dog has gotten sick on the living-room rug, and the laundry (his chore) is still sitting, unfolded, on the couch because he didn’t get around to finishing it. By considering the context, Kevin is able to ascertain that Rhiannon is upset because of these situational factors, rather than because of anything he has said or done.

Culture and You

What cultural contexts are influencing you as you read this book? Consider your gender,ethnicity, academic or socioeconomic background, and other factors. What expectations and goals do you have for this book and this course, and how are they affected by your cultural context?

The Cultural Setting. Finally, we must discuss the fact that all communication takes place within the powerful context of the surrounding culture (represented by the outermost sphere of the competent communication model). Culture is the backdrop for the situational context, the relational context, and the communicators themselves. As discussed earlier, culture helps determine which messages are considered appropriate and effective, and it strongly affects our cognitions. For example, Hannah comes from a culture that shows respect for elders by not questioning their authority and by cherishing possessions that have been passed down in the family for generations. Cole, by contrast, was raised in a culture that encourages him to talk back to and question elders and that values new possessions over old ones. Both Hannah and Cole view their own behaviors as natural—their cognitions about elders and possessions have been influenced by their culture. But when each looks at the other’s behavior, it might seem odd or unnatural. If Hannah and Cole are to become friends, colleagues, or romantic partners, each would benefit from becoming sensitive to the other’s cultural background.

Cultural identity—how individuals view themselves as members of a specific culture—influences the communication choices people make and how they interpret the messages they receive from others (Lindsley, 1999). Cultural identity is reinforced by the messages people receive from those in similar cultures. In our example, both Hannah’s and Cole’s cognitions have been reinforced by their respective friends and family, who share their cultural identity.

LearningCurve

bedfordstmartins.com/commandyou