Self-Efficacy: Assessing Your Own Abilities

Self-Efficacy: Assessing Your Own Abilities

Page 40

The cosmetic industry typically relies on flawless models to sell its products. So how did Lauren Luke—a plain Englishwoman—become a celebrity stylist? Luke began selling cosmetics for a modest profit on eBay. Instead of showing just products, she used them on herself and took photos. Soon she began posting videos on YouTube that she’d taped from her bedroom and was logging more than fifty million views. Luke may not have possessed the star quality of cosmetics spokeswomen like Queen Latifah and Eva Longoria, but she did have confidence in herself and her skills as a makeup artist. She was soon a celebrity in her own right, striking a deal with Sephora and being hailed by Allure magazine as a 2010 “Influencer” (La Ferla, 2009).

Luke’s experiences reveal the power of self-efficacy, which is the third factor influencing our cognitions. Like Luke, you have an overall view of all aspects of yourself (self-concept), as well as an evaluation of how you feel about yourself in a particular area at any given moment in time (self-esteem). Based on this information, you approach a communication situation with an eye toward the likelihood of presenting yourself effectively. According to Albert Bandura (1982), this ability to predict actual success from self-concept and self-esteem is self-efficacy. Your perceptions of self-efficacy guide your ultimate choice of communication situations, making you much more likely to avoid situations where you believe your self-efficacy to be low. Indeed, many people who worry about their ability or inability to make a good impression choose computer-mediated communication (CMC) over face-to-face interactions. Sugitani (2007) found that because CMC (such as e-mail) lacks the nonverbal cues that often reveal our nervousness, we can feel more confident in and better control how we present ourselves through text alone.

Even though a person’s lack of effort is most often caused by perceptions of low efficacy, Bandura (1982) has observed that people with very high levels of self-efficacy sometimes become overconfident. Defending Olympic men’s figure-skating champion Evgeni Plushenko bragged to media that winning the gold in 2010 would be easy; he even held up both index fingers when he finished, as if to say, “Was there any question?” But his overconfidence may have cost him the gold, which went to U.S. skater Evan Lysacek. Bandura recommends that people maintain a high level of self-efficacy with just enough uncertainty to cause them to anticipate the situation accurately and prepare accordingly. To illustrate, a professional athlete might review footage of an opponent’s best plays to keep her competitive edge sharp.

Interpreting Events. Self-efficacy also affects our ability to cope with failure and stress. For instance, feelings of low efficacy may cause you to dwell on your shortcomings. A snowball effect occurs when you already feel inadequate and then fail at something: the failure takes a toll on your self-esteem, causing you to experience stress and negative feelings about yourself. These emotions then bring your self-esteem down even more, which in turn sends your self-efficacy level even lower. For example, Jessie is job hunting but worries that she does not do well in interviews. Every time she goes to an interview and then doesn’t get a job offer, her self-efficacy drops. She lowers her expectations for herself, and her interview performance worsens as well.

By contrast, people with high self-efficacy are less emotionally battered by failures because they usually chalk up disappointments to a “bad day” or some other external factor. When Erin doesn’t get a job she interviewed for, for example, she concludes that she’d stumbled on her words this time because she wasn’t as well prepared as she usually is. Rather than dwelling on the failure, she simply vows to be better prepared for the next interview.

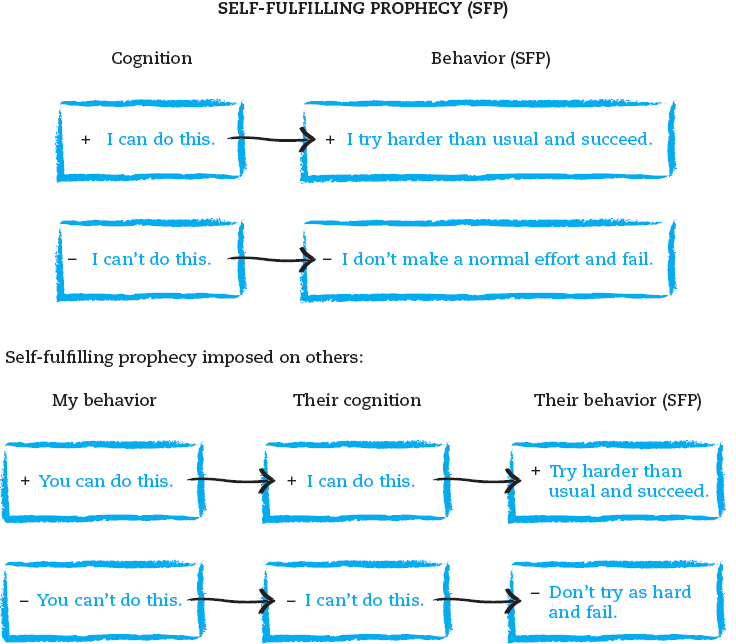

Self-Fulfilling Prophecies. Inaccurate self-efficacy may lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy—a prediction that causes you to change your behavior in a way that makes the prediction more likely to occur. If you go to a party believing that others don’t enjoy your company, for example, you’ll probably stand in a corner, not talking to anyone and making no effort to be friendly. Others won’t like you, so your prophecy gets fulfilled. But your problem began before you even reached the party. You had anticipated that the party might turn out poorly for you based on your understanding of your likability.

Self-efficacy and self-fulfilling prophecy are therefore related. When you cannot avoid situations where you experience low efficacy, you are less likely to make an effort to prepare or participate than you would for situations in which you are comfortable and have high efficacy. When you do not prepare for or participate in a situation (such as the party), your behavior causes the prediction to come true, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy (see Figure 2.3).

Self-fulfilling prophecies don’t always produce negative results. If you announce plans to improve your grades after a lackluster semester and then work harder than usual to accomplish your goal, your prediction may result in an improved report card. But even the simple act of announcing your goals to others—for example, tweeting your intention to quit smoking or to finish a marathon—can create the commitment to make a positive self-fulfilling prophecy come true (Willard & Gramzow, 2008).