Assessing Our Perceptions of Self

Assessing Our Perceptions of Self

Page 42

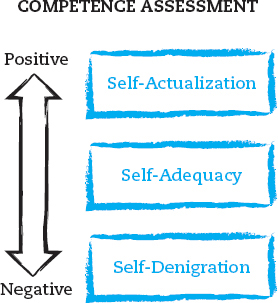

Whenever you communicate, you assess your strengths and weaknesses. These assessments of self are important before, during, and after you have communicated, particularly when you’ve received feedback from other people. You evaluate your expectations, execution, and outcomes in three ways: through self-actualization, through self-adequacy, and through self-denigration.

Self-Actualization. The most positive evaluation you can make about your competence level is referred to as self-actualization—the feelings and thoughts you get when you know that you have negotiated a communication situation as well as you possibly could. At times like these, you have a sense of fulfillment and satisfaction. For example, Shari, a school psychologist, was having problems with the third-grade teacher of one of the students she counsels. The teacher seemed uninterested in the student’s performance, would not return Shari’s phone calls or e-mails, and seemed curt and aloof when they did speak. Shari finally decided to confront the teacher. Although she was nervous at first about saying the right thing, she later felt very good about the experience. The teacher had seemed shocked at the criticism but offered an apology. At the end of the meeting, Shari was quite content that she had been honest and assertive, as well as fair and understanding. This positive assessment of her behavior led to a higher level of self-esteem. When Shari needs to confront someone in the future, she will likely feel more confident about doing so.

Self-Adequacy. At times you may think that your communication performance was not stellar, but it was good enough. When you assess your communication competence as sufficient or acceptable, you feel a sense of self-adequacy, which is less intensely positive than self-actualization. Feelings of self-adequacy can lead you in two directions: to contentment or to a desire for self-improvement.

Suppose that Phil has been working hard to improve his public speaking abilities and does a satisfactory job when he speaks to his fraternity about its goals for charitable work in the coming year. He might feel very satisfied about his speech, but he realizes that with a little more effort and practice, he could have been even more persuasive. In this case, Phil’s reaction is one of self-improvement. He tells himself that he wants to be more competent in his communication, regardless of his current level.

While self-improvement is a good motivation, in some circumstances being satisfied or content with your self-adequacy is sufficient. For example, Lilia has a long history of communication difficulties with her mother. Their relationship is characterized by sarcastic and unkind comments and interactions. But during her last visit home, Lilia and her mother managed not to get into an argument. So Lilia felt good about her communication with her mom. The two didn’t become best friends or resolve all their old problems, but Lilia thought she communicated well under the circumstances. She was content with her self-adequacy.

Self-Denigration. The most negative assessment you can make about a communication experience is self-denigration: criticizing or attacking yourself. This occurs most often when communicators overemphasize their weaknesses or shortcomings (“I knew I’d end up fumbling over my words and repeating myself—I am such a klutz!”). Most self-denigration is unnecessary and unwarranted. Even more important, it prevents real improvement. Hunter, for example, thinks that he can’t talk to his sister; he perceives her as stubborn and judgmental. Hunter says, “I know my sister won’t listen. In her opinion, I can’t do anything right.” Hunter needs to assess his communication behaviors: what specific words and nonverbal behaviors (like tone of voice) does he use with his sister? He must avoid self-denigration by focusing on times when he has had positive communication with his sister. He can also plan for communication improvement (“Next time, I will listen to my sister until she is finished talking before I say anything back to her”). Thus our assessments of our competence run from self-actualization on the positive end of the spectrum to self-denigration on the negative end (see Figure 2.4).

LearningCurve

bedfordstmartins.com/commandyou