Unethical Listening Behaviors

Unethical Listening Behaviors

Page 131

We may all be guilty of unethical listening behaviors from time to time (Beard, 2009; Lipari, 2009). These include defensive listening, selective listening, selfish listening, hurtful listening, and pseudolistening, all discussed in this section. Such behaviors will not benefit you in any way personally or professionally. But with careful attention and the development of positive listening behaviors, you can overcome them.

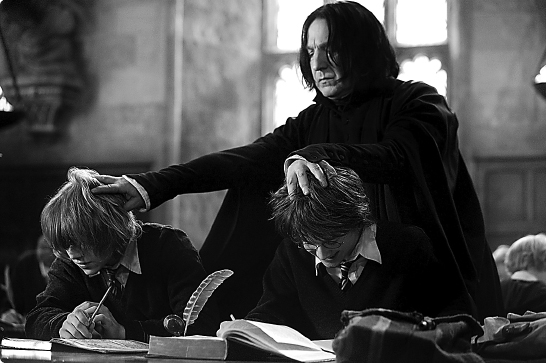

Defensive Listening. If you’ve ever read the Harry Potter series of books or seen the movies, you know that Harry Potter can’t stand Professor Snape and that Professor Snape despises Harry. To some extent, the mutual dislike is earned: Snape often singles Harry out for punishment, and Harry frequently disrespects Snape. Throughout the series, their preconceived notions of one another hamper their communication. When Snape tries to teach Harry a crucial skill, Harry refuses to listen to the valuable advice and corrections. In Harry’s eyes, Snape is picking on him yet again, trying to make him feel like a failure, so he simply shuts down and responds with anger. Snape, on the other hand, refuses to acknowledge any talent or hard work on Harry’s part. Both characters, because of their mutual dislike and distrust, are guilty of defensive listening, responding with aggression and arguing with the speaker without fully listening to the message.

We’ve all been in situations in which someone seems to be confronting us about an unpleasant topic. But if you respond with aggressiveness and argue before completely listening to the speaker, you’ll experience more anxiety, probably because you’ll anticipate not being effective in the listening encounter (Schrodt & Wheeless, 2001). If you find yourself listening defensively, consider the tips shown in Table 6.2.

| Table 6.2 Steps to Avoid Defensive Listening | |

| Tip | Example |

| Hear the speaker out | Don’t rush into an argument without knowing the other person’s position. Wait for the speaker to finish before constructing your own arguments. |

| Consider the speaker’s motivations | Think of the speaker’s reasons for saying what is being said. The person may be tired, ill, or frustrated. Don’t take it personally. |

| Use nonverbal communication | Take a deep breath and smile slightly (but sincerely) at the speaker. Your disarming behavior may be enough to force the speaker to speak more reasonably. |

| Provide calm feedback | After the speaker finishes, repeat what you think was said and ask if you understood the message correctly. Often a speaker on the offensive will back away from an aggressive stance when confronted with an attempt at understanding. |

Source: Wheeless (1975). Adapted with permission.

Selective Listening. When you zero in only on bits of information that interest you, disregarding other messages or parts of messages, you are engaging in selective listening. Selective listening is common in situations where you are feeling defensive or insecure. For example, if you really hate working on a group project with your classmate Lara, you may only pay attention to the disagreeable or negative things that she says. If she says, “I can’t make it to the meeting on Thursday at eight,” you shut off, placing another check in the “Lara is lazy” column of proof. However, you might miss the rest of Lara’s message—perhaps she has a good reason for missing the meeting or maybe she’s suggesting that you reschedule.

Selective listening can work with positive messages and impressions as well, although it is equally unethical in such situations. Imagine that you’re a manager at a small company. Four of your five employees were in place when you took your job, but you were the one who hired Micah. Since hiring well makes you look good as a manager, you might tend to focus on Micah’s accomplishments and the feedback from others in the organization about Micah’s performance. He may be a great employee, but you should listen to compliments about other employees as well, particularly when making decisions about promotions.

To improve our communication, particularly when we’re feeling apprehensive or defensive, we must take care not to avoid particular messages or close our ears to communication that makes us uncomfortable. Being mindful of our tendency to behave in this manner is the first step in addressing this common communication pitfall.

Selfish Listening. Selfish listeners hear only the information that they find useful for achieving specific goals. For example, your colleague Lucia may seem really engaged in your discussion about some negative interactions you’ve had with Ryan, your boyfriend. But if she’s only listening because she’s interested in Ryan and wants to get a sense of your relationship’s vulnerability, then she’s listening selfishly.

Selfish listening can also be monopolistic listening, or listening to control the communication interaction. We’re all guilty of this to some degree—particularly when we’re engaged in conflict situations. Suppose your grades declined last semester. Your father says, “I really think you need to focus more on school. I’m not sure I want to shell out more money for tuition next semester if your grades get worse.” You may not take his advice seriously if all you’re doing while he’s talking is plotting a response that will persuade him to pay next semester’s tuition.

Hurtful Listening. Hurtful listening also focuses on the self, but it’s more direct—and perhaps even more unethical—than selfish listening. Attacking is a response to someone else’s message with negative evaluations (“That was a stupid thing to say!”). Ambushing is more strategic. An ambusher listens specifically to find weaknesses in others—things they’re sensitive about—and pulls those weaknesses out at strategic or embarrassing times. So if Mai cries to Scott about failing her calculus final and Scott is later looking for a way to discredit Mai, he might say something like, “I’m not sure you’re the right person to help us draw up a budget, Mai. Math isn’t exactly your strong suit, is it?”

Ethics and You

Do you know any people who engage in the unethical listening behaviors described? Is that behavior frequent or a rare slip? How do these tendencies affect your interactions with these people? Do you ever find yourself engaging in such unethical behaviors?

At other times, we don’t intend our listening to be hurtful, but we still end up offending others or being inconsiderate of their feelings. Insensitive listening occurs when we fail to pay attention to the emotional content of someone’s message, instead taking it at face value. Your friend Adam calls to tell you that he got rejected from Duke Law School. Adam had mentioned to you that his LSAT scores made Duke a long shot, so you accept his message for what it appears to be: a factual statement about a situation. But you fail to hear the disappointment in his voice—even if Duke was a long shot, it was his top choice as well as a chance to be geographically closer to his partner, who lives in North Carolina. Had you paid attention to Adam’s nonverbal cues, you might have known that he needed some comforting words.

Pseudolistening. When you become impatient or bored with someone’s communication messages, you may find yourself engaging in pseudolistening—pretending to listen by nodding or saying “uh-huh” when you’re really not paying attention at all. One of the many downsides of pseudolistening is that you can actually miss important information or offend your communication partner and damage the relationship. Pseudolistening is a common trope in television sitcoms—when Homer Simpson nods absently (daydreaming about food or some other inappropriate topic) even though he hasn’t listened to a word his boss has said, we find it funny and perhaps a little familiar. But in real life, implying that we have listened when we have not can have disastrous consequences: we miss instructions, neglect tasks that we have implied we would complete, and fail to meet others’ needs.

LearningCurve

bedfordstmartins.com/commandyou