Group Networks

Group Networks

Page 197

Just as a group’s size strongly influences communication within the group, so do networks. Networks are patterns of interaction governing who speaks with whom in a group and about what. To understand the nature of networks, you must first consider two main positions within them. The first is centrality, or the degree to which an individual sends and receives messages from others in the group. The most central person in the group receives and sends the highest number of messages in a given time period. At the other end of the spectrum is isolation—a position from which a group member sends and receives fewer messages than other members.

A team leader or manager typically has the highest level of centrality in a formal group, but centrality is not necessarily related to status or power. The CEO of a company, for example, may be the end recipient of all information generated by teams below her, but in fact only a limited number of individuals within the organization are able to communicate directly with her. Her assistant, conversely, may have a higher degree of centrality in the network. As you might imagine, networks play a powerful role in any group’s communication, whether the group is a family, a sports team, a civic organization, or a large corporation.

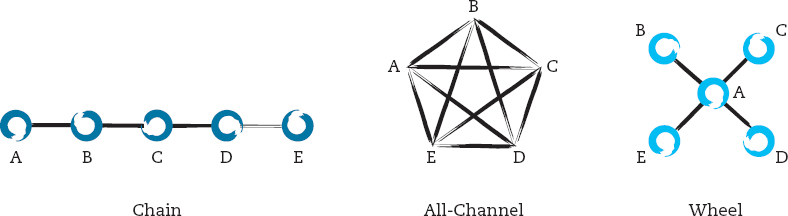

In some groups, all members speak with all others regularly about a wide range of topics. In others, perhaps only a few members are “allowed” to speak directly with the group’s leader or longest-standing member about serious issues. In still other groups, some members may work alongside one another without communicating at all. There are several types of networks, including chain networks, all-channel networks, and wheel networks (see Figure 9.2) (Bavelous, 1950).

Source: Scott (1981), p. 8. Adapted with permission.

Chain Networks. In a chain network, information is passed from one member to the next rather than shared among members. Such networks can be practical for sharing written information: an e-mail forwarded from person to person along a chain, for example, allows each person to read the original information from prior recipients. But this form of group communication can lead to frustration and miscommunication when information is conveyed through ways that are easier to distort, such as spoken words. Person A tells person B that their boss, Luis, had a fender bender on the way to work and will miss the 10:00 A.M. meeting. Person B tells person C that Luis was in an accident and will not be in the office today. Person C tells person D that Luis was injured in an accident; no one knows when he’ll be in. You can imagine that Luis will be in a full-body cast by the time the message reaches person G!

All-Channel Networks. In an all-channel network, all members are an equal distance from one another, and all members interact with each other. When people talk about roundtable discussions, they’re talking about all-channel groups: there is no leader, and all members operate at equal levels of centrality. Such networks can be useful for collaborative projects and for brainstorming ideas, but the lack of order can make it difficult for such groups to complete tasks. Imagine, for example, that you’re trying to arrange a meeting with a group of friends. You send out a mass e-mail to all of them to determine days that will work, and you ask for suggestions about where to meet. Each recipient can simply hit “reply all” and share their response with the group. By using an all-channel network, the entire group learns that Friday is not good for anyone, but Saturday is; and while a few people have suggested favorite spots, there’s no consensus on where to go. That’s where wheel networks come in.

Wheel Networks. Wheel networks are a sensible alternative for situations in which individual members’ activities and contributions must be culled and tracked in order to avoid duplicating efforts and to ensure that all tasks are being completed. In a wheel network, one individual acts as a touchstone for all the others in the group; all group members share their information with that one individual, who then shares the information with the rest of the group. Consider the preceding example: as the sender of the initial e-mail, you might take on a leadership role and ask everyone to reply just to you. Then you could follow up with a decision about a time and place to meet and send that out to everyone else. Wheel networks have the lowest shared centrality but are very efficient (Leavitt, 1951).

LearningCurve

bedfordstmartins.com/commandyou