The Negative Real Shock Dilemma

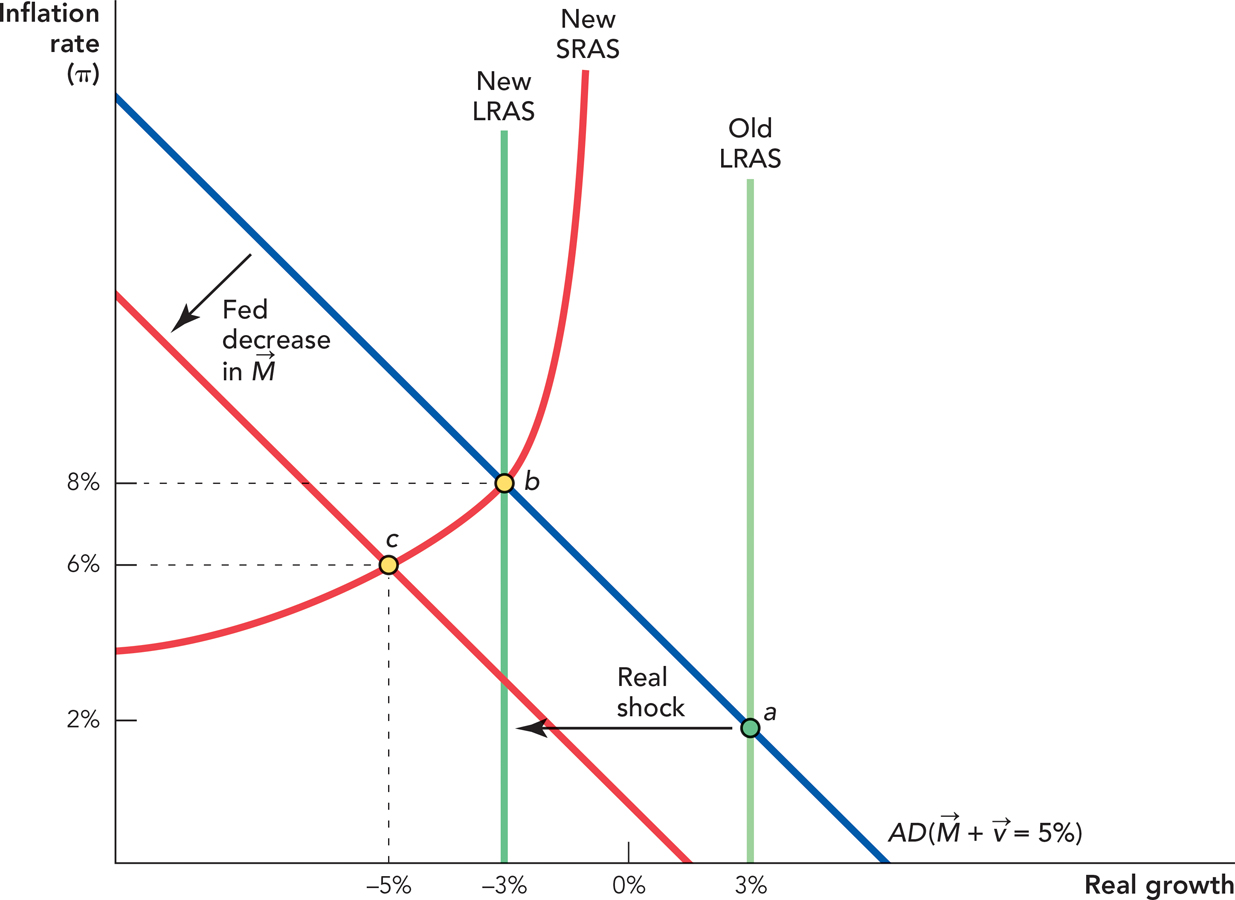

A very difficult case for monetary policy is when the economy is hit by a negative real shock such as a rapid oil price increase. As we saw in Chapter 32 and Chapter 33, a negative real shock shifts the long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) curve to the left, moving the equilibrium from point a to point b, as shown in Figure 35.3. That means a higher rate of price inflation and a lower growth rate for GDP, again as previously covered. How should monetary policy respond?

, moving the economy to point c with a lower inflation rate but an even lower growth rate. Note that for clarity we have suppresed the old SRAS curve running through point a.

, moving the economy to point c with a lower inflation rate but an even lower growth rate. Note that for clarity we have suppresed the old SRAS curve running through point a.One approach is to focus on the inflation rate, which has jumped from 2% to 8%. What is the recipe for reducing inflation? Correct—a decrease in  . In the 1970s, for example, the Federal Reserve often responded to supply shocks, such as an oil shock, by decreasing

. In the 1970s, for example, the Federal Reserve often responded to supply shocks, such as an oil shock, by decreasing  and reducing aggregate demand. That means taking the AD curve and shifting it farther back to the left through the use of monetary policy. In Figure 35.3, we show the new equilibrium at point c. The reduction in

and reducing aggregate demand. That means taking the AD curve and shifting it farther back to the left through the use of monetary policy. In Figure 35.3, we show the new equilibrium at point c. The reduction in  reduces the inflation rate from 8% to 6%, but also reduces economic growth and by more than the supply shock alone would have done.

reduces the inflation rate from 8% to 6%, but also reduces economic growth and by more than the supply shock alone would have done.

Some economists have argued that the Federal Reserve’s actions in trying to stem inflation were even worse for the economy than the oil shocks. Interestingly, the most prominent critic of the Federal Reserve’s actions in the 1970s was Ben Bernanke. Consistent with his criticism, when he was Fed chairman and faced with rising oil prices in 2007–2008, he did not contract the rate of growth of the money supply.1

347

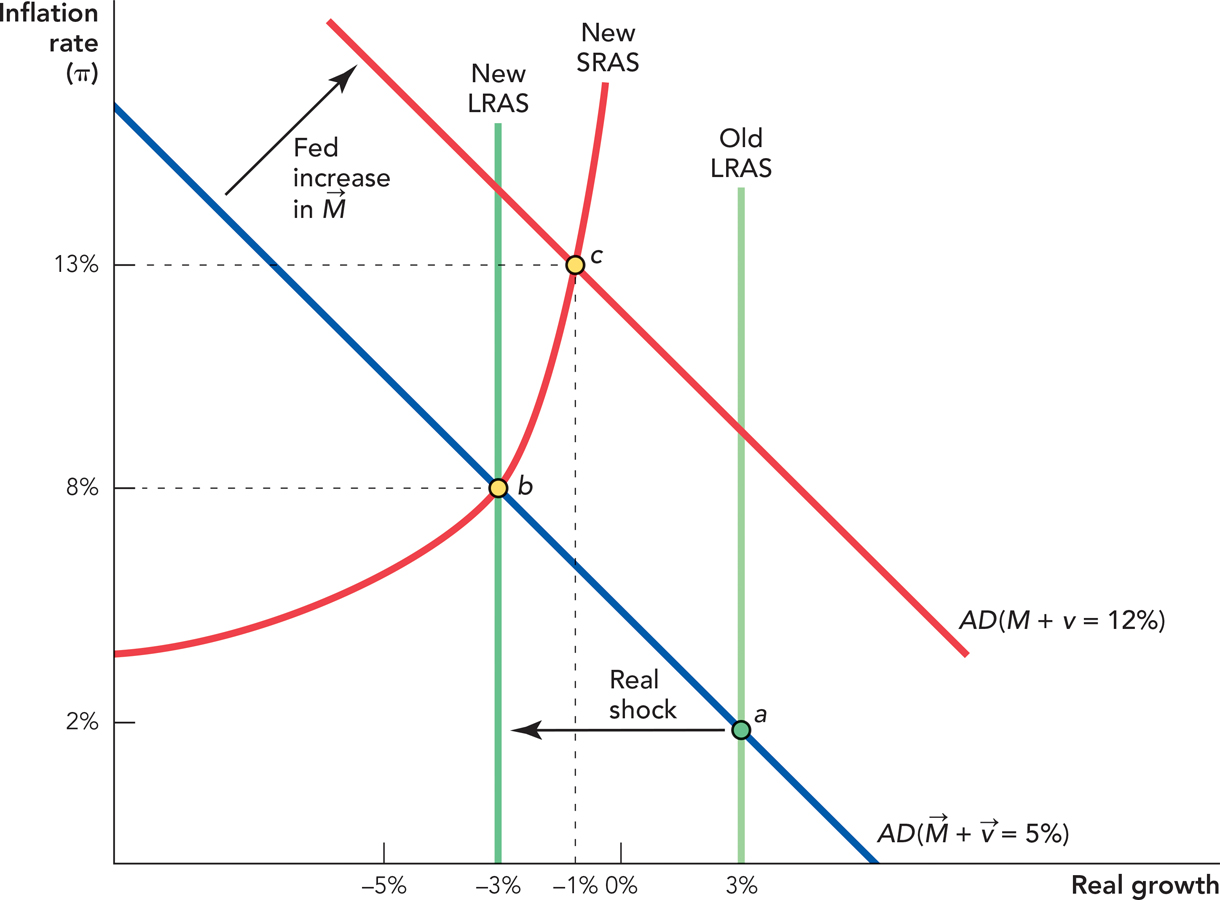

Today, central bankers are more likely to believe that a central bank should respond to a negative real shock by increasing aggregate demand but that, too, has its problems.

As before, the Federal Reserve can increase aggregate demand by increasing the money growth rate, but now the economy is less productive than before, due to the real shock. As a result, an increase in  will not move the economy back to point a. Instead, most of the increase in

will not move the economy back to point a. Instead, most of the increase in  will show up in inflation rather than in real growth so the economy will shift from point b to point c in Figure 35.4 below with a much higher inflation rate and a slightly higher growth rate.

will show up in inflation rather than in real growth so the economy will shift from point b to point c in Figure 35.4 below with a much higher inflation rate and a slightly higher growth rate.

moving the economy to point c with a little bit higher growth rate but a much higher inflation rate. Note that for clarity we have suppresed the old SRAS curve running through point a.

moving the economy to point c with a little bit higher growth rate but a much higher inflation rate. Note that for clarity we have suppresed the old SRAS curve running through point a.Is it worthwhile responding to a real shock with an increase in AD? Maybe not. Although an increase in  may increase the growth rate a little, the inflation rate increases by a lot and, as we just saw in our discussion of the Volcker disinflation, higher inflation now can cause serious problems later. In particular, if the inflation rate gets too high, the Fed has to reduce inflation, thereby creating a lot of unemployment. Perhaps you wondered in the previous section on engineering a disinflation, why the rate of inflation might have ended up too high in the first place. Now you know at least one way inflation can end up too high and that also helps us understand why the dilemmas of monetary policy arise so frequently.

may increase the growth rate a little, the inflation rate increases by a lot and, as we just saw in our discussion of the Volcker disinflation, higher inflation now can cause serious problems later. In particular, if the inflation rate gets too high, the Fed has to reduce inflation, thereby creating a lot of unemployment. Perhaps you wondered in the previous section on engineering a disinflation, why the rate of inflation might have ended up too high in the first place. Now you know at least one way inflation can end up too high and that also helps us understand why the dilemmas of monetary policy arise so frequently.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 35.2

If the Fed wanted to restore some growth in the economy to deal with high unemployment, what would it do? What would be the problem of acting in this way?

If the Fed wanted to restore some growth in the economy to deal with high unemployment, what would it do? What would be the problem of acting in this way?

Question 35.3

Suppose that the Fed reacts to a series of negative real shocks by increasing AD every time. What will happen to the inflation rate?

Suppose that the Fed reacts to a series of negative real shocks by increasing AD every time. What will happen to the inflation rate?

Moreover, recall from Chapter 32 and Chapter 33 that real shocks are often accompanied by aggregate demand shocks so the figures are considerably simplified. Confused? Don’t worry, that is exactly how the economists at the Federal Reserve feel. We are quite serious when we say that a combination of shocks can confuse economists at the Federal Reserve. Don’t forget that in addition to the problems you face as students, the Federal Reserve is looking at real-time data, which as we have noted are often uncertain and subject to revision.

348

The bottom line is that with a real shock, the central bank faces a dilemma: It must choose between too low a rate of growth (with a high rate of unemployment) and too high a rate of inflation. The central bank, in fact, stands a good chance of getting a mix of both problems. The lesson is this: If you are a central banker, hope that you don’t face too many negative real shocks in your term!