Check Yourself Solutions for Chapter 32 through Chapter 35

Chapter 32-1

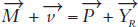

Because

in the AD/AS model, if

in the AD/AS model, if  equals 7% and

equals 7% and  equals 0%, by definition inflation plus real growth will equal 7%. If in this situation we find that real growth equals 0%, then inflation must be 7%.

equals 0%, by definition inflation plus real growth will equal 7%. If in this situation we find that real growth equals 0%, then inflation must be 7%.Increased spending growth shifts the aggregate demand curve outward.

Chapter 32-2

Putting down phone lines is very expensive, compared to the cost of putting up cell phone towers. Cell phones have improved communications in all countries, but the change has been most dramatic in less developed countries. This has been a positive shock throughout the world.

A large and sudden increase in taxes would suppress economic activity especially in the short run as consumers and firms reallocated from more energy-intensive sectors of the economy to less energy-intensive sectors. The reallocation would decrease the fundamental capacity of the economy to produce goods and services, which is a shift of the long-run aggregate supply curve to the left.

B-11

Chapter 32-3

The long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical because price and wage stickiness does not affect the fundamental productive capacity off the economy over the long run. However, price and wage stickiness does affect aggregate supply in the short run, and this accounts for the fact that the SRAS curve is not vertical.

In the short run, inflation expectations may deviate from actual inflation, and spending growth can lead to some GDP growth.

In the long run, inflation expectations equal actual inflation.

Chapter 32-4

In the long run, unexpected inflation always becomes expected inflation.

If consumers fear a recession and cut back on their expenditures, the aggregate demand curve will shift inward.

Chapter 32-5

The U.S. money supply fell in the early 1930s. This initially affected aggregate demand (the AD curve shifted inward—down/left), not the long-run aggregate supply curve. The decrease in aggregate demand resulted in bank failures that decreased the productivity of financial intermediation, which was a real shock, and so affected the long-run aggregate supply curve, shifting it to the left.

In an ordinary year, the real shocks of the 1930s might have been shrugged off but the combination of large shocks to AD and real shocks at the same time made the Great Depression great.

Chapter 33-1

The 9/11 attacks brought a high level of uncertainty into the economy. No one knew if more attacks were planned so no one wanted to be on an airplane. Cutting back on air travel hurt the airlines and all associated businesses: airports, airport services such as food vendors, companies that provide transportation to and from airports. When no one flew on airplanes to take business trips, some local business trips were still undertaken (by train or car), but longer trips (such as cross-country travel) came to a standstill. As travel declined, so did the need for hotel rooms and restaurant meals. Hotels were hit hard: Cutting the price of hotel rooms had little effect when uncertainty dried up business travel. The near-cessation in business travel amplified the economic effects of the attacks nationwide: The attacks in New York City and Washington, D.C., had nationwide repercussions.

Chapter 34-1

The monetary base is defined as currency plus reserves held by banks at the Fed.

B-12

In February 2014, there was $1,172 billion of currency in the United States compared to around $1,556 billion in checkable deposits. Thus, currency accounts for slightly less than checkable deposits.

Chapter 34-2

If the reserve ratio is 1/20, then 5% of deposits are kept as reserves.

If the reserve ratio is 1/20, then the money multiplier is 20.

If the Fed increases bank reserves by $10,000 and the reserve ratio is 1/20, then the change in the money supply is $200,000.

Chapter 34-3

The Fed wants to lower interest rates. It does so by buying bonds in open market operations. By doing this, the Fed adds reserves and through the multiplier process, it increases the money supply.

Chapter 34-4

The Fed might not let a large bank fail if it fears systemic risk, the possibility that the failure will bring down other banks and financial institutions. In this case, the Fed will use its powers as the lender of last resort to support a bank that is “too big to fail.”

Moral hazard increases my incentives to double my bet to make up for a large loss. If the Fed always bails out large banks, my actions will never lead to the bank’s bankruptcy, so why not take the chance?

Chapter 34-5

Money is neutral in the long run but has a short-run effect on the economy. This explains the Fed’s concerns with the money supply in the short run.

If banks are afraid of a recession, they will be more reluctant to lend. This will hamper the Fed’s ability to shift aggregate demand in a recession. In this case, the Fed is sometimes said to be “pushing on a string.”

Chapter 35-1

Data problems affect the Fed’s ability to set monetary policy that is “just right” because they make it difficult for the Fed to determine just what is going on with the economy. If the Fed does not know exactly what is going on, it cannot prescribe the correct medicine.

Chapter 35-2

If the Fed wanted to restore some growth to the economy, it could work to increase aggregate demand. The problem is that increasing growth in this case comes at the expense of adding more inflation. This is the policy dilemma.

B-13

If the Fed increases AD every time in response to a series of negative real shocks, the inflation rate will climb. Eventually, the Fed will have to act to reduce inflation, possibly pushing the economy into a recession.

Chapter 35-3

The Fed can never be certain when asset prices reach the bubble stage. Bubbles are easier to identify with hindsight, but even then identification is a judgment call.

Collateral damage to a contraction in the money supply could be reducing the growth rate for GDP for the broader economy as a whole.

Chapter 35-4

Milton Friedman argued for a 3% money growth rate because the long-run growth rate for the U.S. economy trends around 3%. When money growth equals long-run growth in the economy, there will be a tendency for price stability.