Cyclical Unemployment

Cyclical unemployment is unemployment correlated with the business cycle.

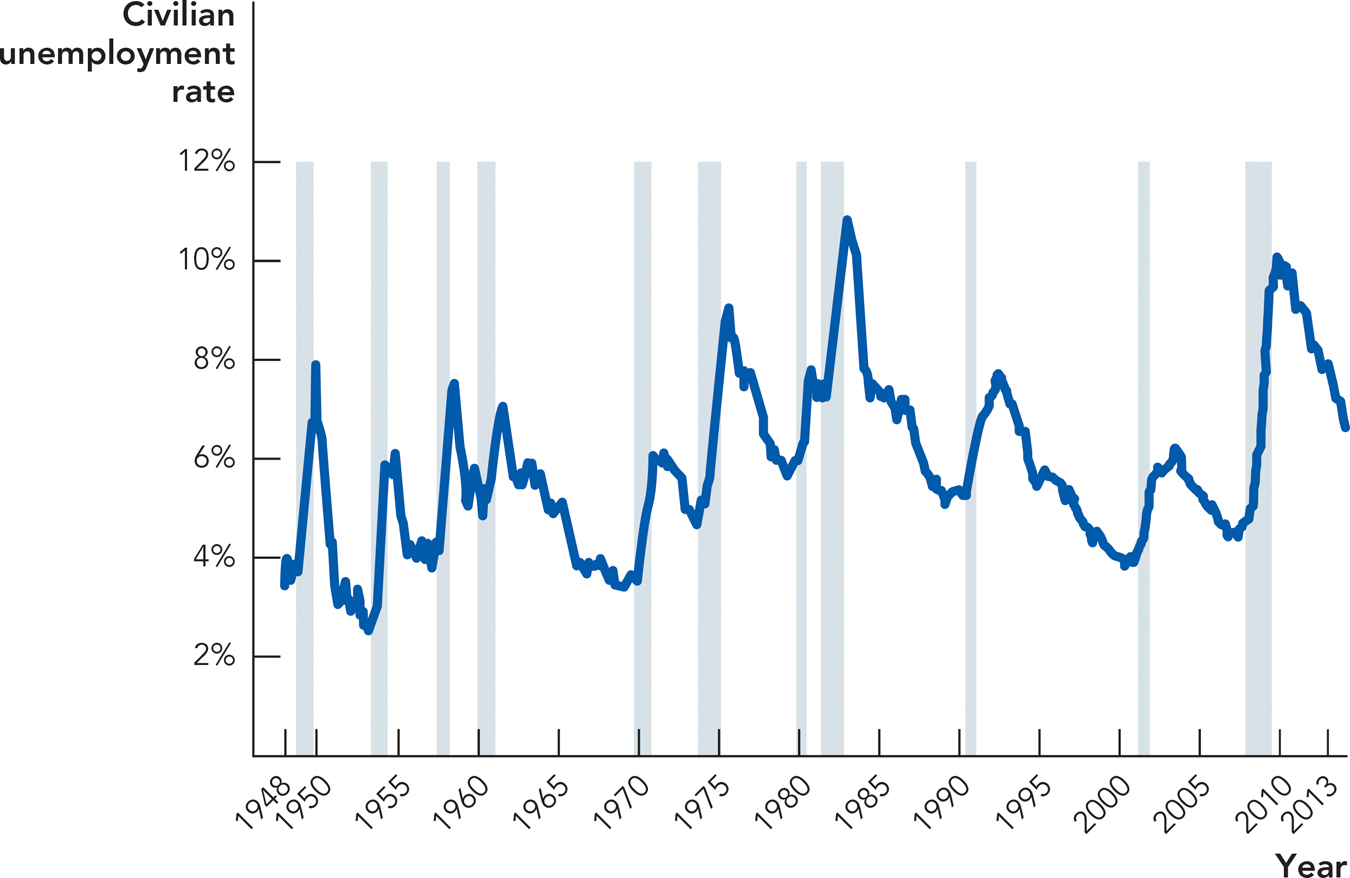

The final category of unemployment is cyclical unemployment, or unemployment correlated with the ups and downs of the business cycle. Figure 11.6 below graphs the U.S. unemployment rate since 1948. The shaded areas are recessions. Notice that during every recession, unemployment increases dramatically.

Note: Recessions are shaded.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics; National Bureau of Economic Research.

236

Lower growth is usually accompanied with higher unemployment for two reasons. First and most obviously, when GDP is falling, firms often lay off workers, which increases unemployment. The second reason is more subtle. Higher unemployment means that fewer workers are producing goods and services. When workers are sitting idle, it’s likely that related capital is also sitting idle (e.g., factories are boarded up). An economy with idle labor and idle capital cannot be maximizing growth, and that will hurt the ability of that economy to create more jobs.

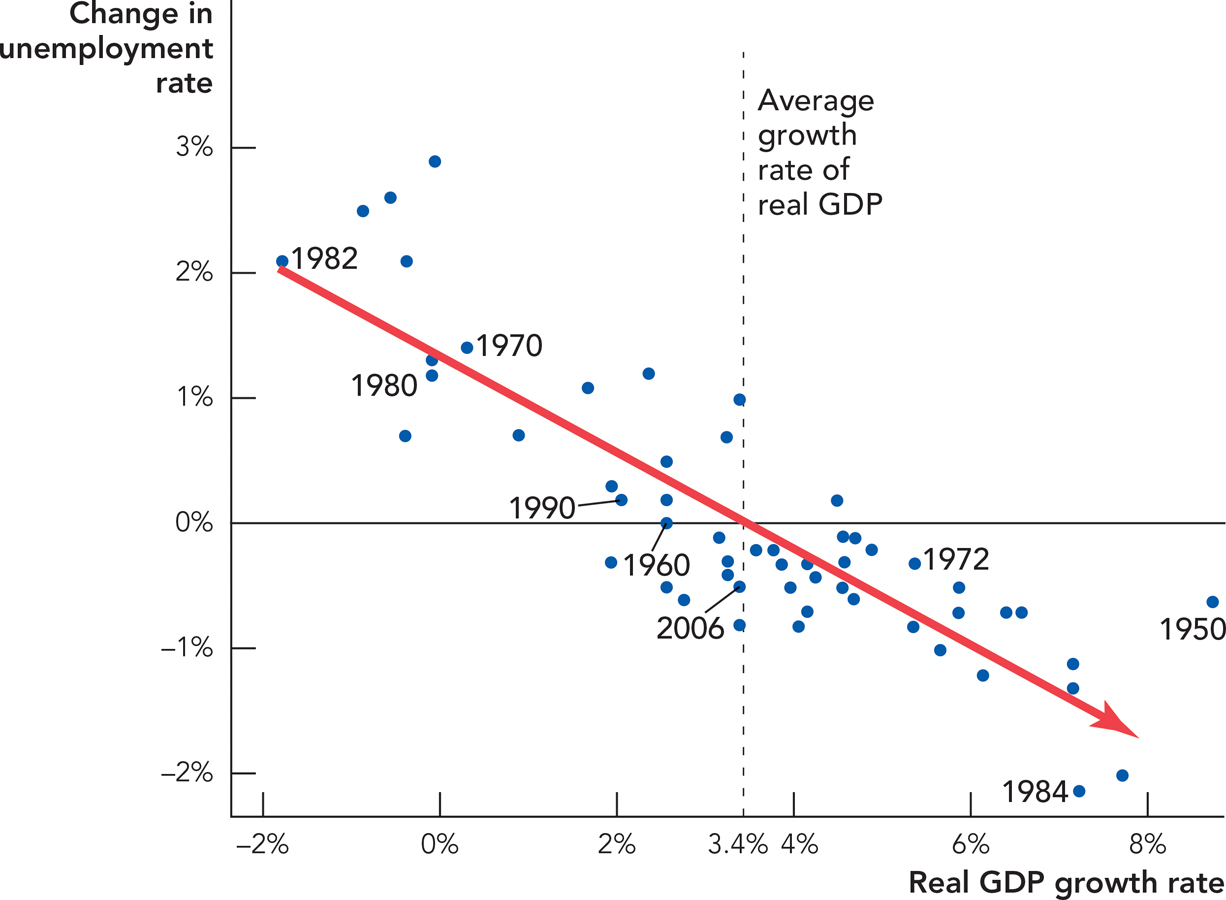

Figure 11.7 emphasizes the flip side of the idea that lower growth is correlated with increases in unemployment—faster growth is correlated with decreases in unemployment. Figure 11.7 plots changes in the U.S. unemployment rate on the vertical axis against growth on the horizontal axis. As you can see, faster growth in real GDP decreases unemployment. In fact, unemployment tends to fall when growth is above average and it tends to rise when growth is below average. Consider 1982 when the economy was in a deep recession and the unemployment rate increased by 2.1%. On the other hand, just two years later in 1984, real GDP was growing rapidly at 7.2% a year, unemployment was falling, and, partly as a consequence, Ronald Reagan was reelected in a landslide.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Although we define cyclical unemployment as unemployment correlated with the business cycle, the cause of cyclical unemployment is a subject of debate among economists, largely because the cause of business cycles is a subject of debate. Some economists think that business cycles are mostly a response to real shocks that require a reallocation of labor across industries. For these economists, a business cycle is nothing more than the economic growth process in action—growth is volatile, not smooth. Thus, for these economists, cyclical unemployment is just another example of frictional and structural unemployment.

237

Other economists, typically of the “Keynesian” persuasion, think that cyclical unemployment is caused by deficiencies in aggregate demand. This concept will be explained in later chapters, but for the time being, we can think of this notion of cyclical unemployment as caused by a mismatch between the aggregate level of wages in an economy and the level of prices. The wages demanded by workers are out of synch with the level of prices, so workers are too expensive to hire from the point of view of firms.

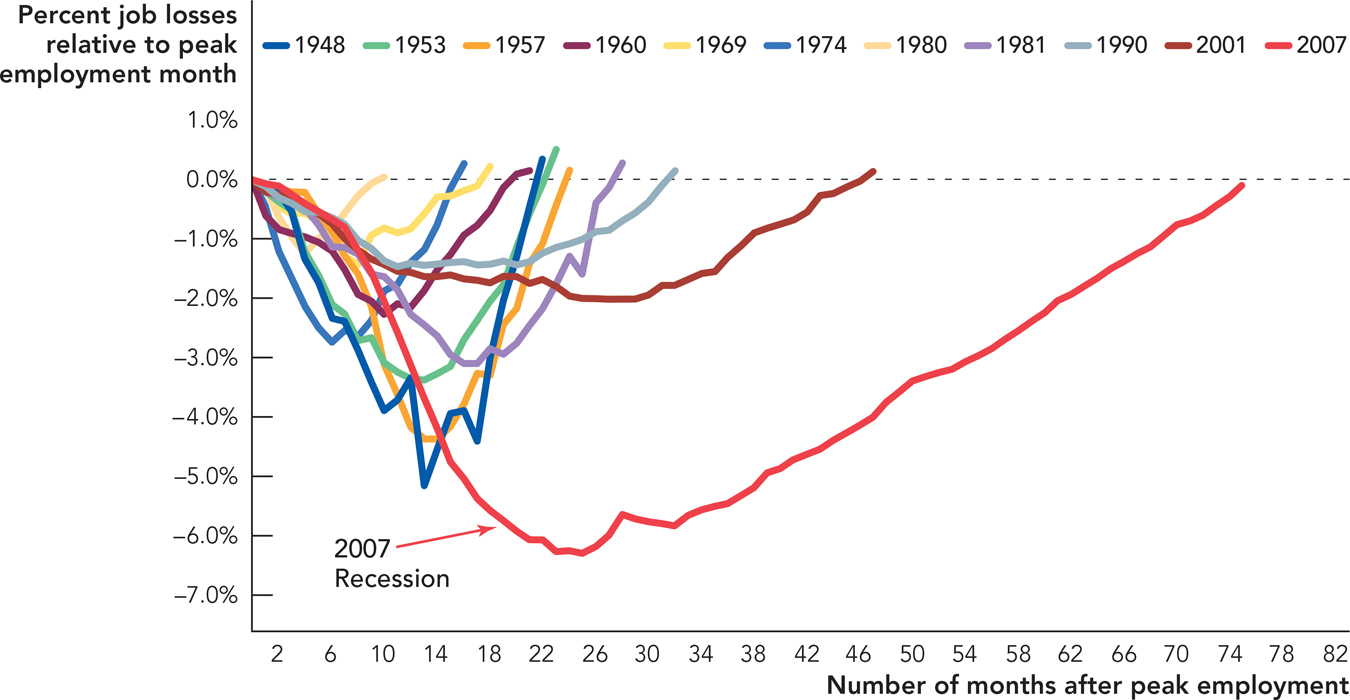

To give a simple example, whether a firm wants to hire another worker depends not only on the wage of that worker but also on that wage relative to the price of the firm’s product (and, of course, relative to other prices more generally). If Apple can sell an iPod for $200, it is more likely to step up production and hire more workers than if Apple can sell an iPod for $100. Yet when potential workers make wage demands, they are not always fully aware of the prices and thus the profits available to their employers. Wage demands can be too high, relative to what the firm finds profitable, and this mismatch gives rise to cyclical unemployment. Yet if aggregate demand for goods and services was somehow higher, the higher wage demands perhaps could be justified and the workers could be hired. In any case, we see that cyclical unemployment, following the recent recession, remained high in 2010, even compared with previous recessions. This is sometimes called a “jobless recovery.” Figure 11.8 shows that for the recession beginning in 2007 it took more than six years for employment to return to its prerecession level, the longest for any recession since the Great Depression.

Source: http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/.

238

We will return to the concepts of real shocks, mismatches between aggregate wages and prices, business uncertainty, and potential government policy to reduce cyclical unemployment in greater detail in Chapter 13, Chapter 14, Chapter 16, and Chapter 18. This will help us explain why the 2009-2010 labor market was so slow to move to higher levels of employment.

The Natural Unemployment Rate

The natural unemployment rate is the rate of structural plus frictional unemployment.

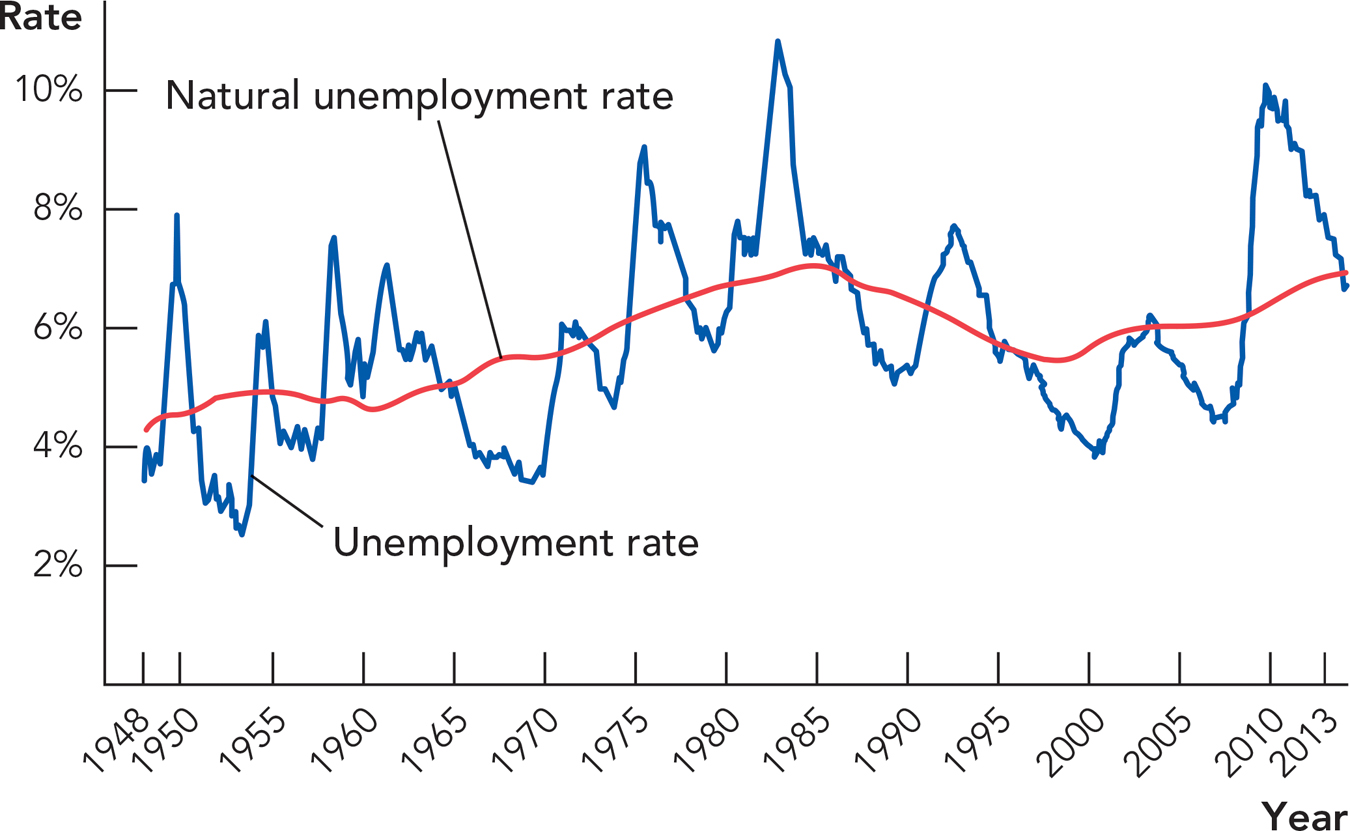

The natural unemployment rate is defined as the rate of structural plus frictional unemployment. Economists typically think of the underlying rates of frictional and structural unemployment as changing only slowly through time as major, long-lasting features of the economy change. Cyclical employment, however, can increase or decrease dramatically over a matter of months. Figure 11.9 plots one estimate of the natural rate against the actual unemployment rate. The natural rate changes only slowly through time and the actual rate of unemployment varies around the natural rate.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics and author calculations.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 11.5

What happens to cyclical unemployment during the business cycle?

What happens to cyclical unemployment during the business cycle?

Question 11.6

How are economic growth and unemployment related?

How are economic growth and unemployment related?

The concepts of cyclical, structural, and frictional unemployment are not always clear and distinct. If times are good, an employer will place more ads and search harder for workers. We might say that the frictional rate of unemployment has fallen, but we also might say that the cyclical rate of unemployment has fallen. Both descriptions of the improvement are true. Similarly, how well an economy absorbs, say, displaced auto workers (structural unemployment) will depend on the overall strength of economic conditions. One type of unemployment can even turn into another. Cyclical unemployment, for example, can turn into structural unemployment if workers remain unemployed for too long, thereby leading to a decline in skills and employment prospects. As we showed earlier, the increase in unemployment that began with the 2007-2009 recession is taking a very long time to decline, leading to worries that unemployment that perhaps started out as cyclical may become structural.

239

Most economists view observed unemployment as a mix of structural, frictional, and cyclical characteristics. The three categories nonetheless give us some useful ideas for organizing the sources of unemployment.