Voter Myopia and Political Business Cycles

We turn now from the microeconomics of political economy to an application in macroeconomics. Rational ignorance and another factor, voter myopia, can encourage politicians to boost the economy before an election in order to increase their chances of reelection.

Presidential elections appear to be fought on many fronts. Candidates battle over education, war, health care, the environment, and the economy. Pundits scrutinize the daily chronicle of events to divine how the candidates advance and retreat in public opinion. Personalities and “leadership” loom large and are reckoned to swing voters one way or other. When the battle is done, historians mark one personality and set of issues as having won the day and as reflecting the “will of the voters.”

But economists and political scientists have been surprised to discover that a simpler logic underlies this apparent chaos of seemingly unique and momentous events. Over the past 100 years, the American voter has voted for the party of the incumbent when the economy is doing well and voted against the incumbent when the economy is doing poorly. Voters are so responsive to economic conditions that the winner of a presidential election can be predicted with considerable accuracy, even if one knows nothing about the personalities, issues, or events that seem, on the surface, to matter so much.

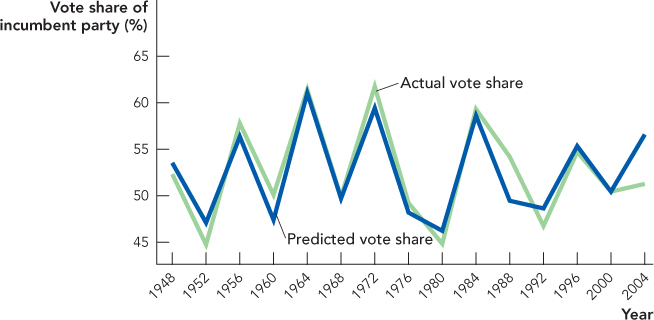

The green line in Figure 21.1 shows, for each presidential election since 1948, the share of the two-party vote won by the party of the incumbent (that is, a share greater than 50% usually means the presidency stayed with the incumbent party and a share less than 50% usually means the presidency switched party). The blue line is the share of the two-party vote predicted by just three variables: growth in personal disposable income (per capita) in the year of the election, the inflation rate in the year of the election, and a simple measure of how long the incumbent party has been in power. Notice that these three variables alone give us great power to predict election results.

Actual vote share is the share of the two-party vote captured by the party of the presidential incumbent.

460

More specifically, the incumbent party wins elections when personal disposable income is growing, when the inflation rate in the election year is low, and when the incumbent party has not been in power for too many terms in a row. Personal disposable income is the amount of income a person has after taxes. It includes income from wages, dividends, and interest but also income from welfare payments, unemployment insurance, and Social Security payments. The inflation rate is the general increase in prices. The last variable, a measure of how long the incumbent party has been in power, reduces a party’s vote share. Voters seem to get tired or disillusioned with a party the longer it has been in power, so there is a natural tendency for the presidency to switch parties even if all else remains the same.

Figure 21.1 tells us that voters are responsive to economic conditions, but more deeply it tells us that voters are surprisingly responsive to economic conditions in the year of an election. Voters are myopic—they don’t look at economic conditions over a president’s entire term. Instead, they focus on what is close at hand, namely economic conditions the year of an election. Politicians who want to be reelected, therefore, are wise to do whatever they can to increase personal disposable income and reduce inflation in the year of an election even if this means decreases in income and increases in inflation at other times. Is there evidence that politicians behave in this way? Yes.

One of the most brazen examples comes from President Richard Nixon. Just two weeks before the 1972 election, he sent a letter to more than 24 million recipients of Social Security benefits. President Nixon’s letter read:

Higher Social Security Payments

Your social security payment has been increased by 20 percent, starting with this month’s check, by a new statute enacted by Congress and signed into law by President Richard Nixon on July 1, 1972.

The President also signed into law a provision that will allow your social security benefits to increase automatically if the cost of living goes up. Automatic benefit increases will be added to your check in future years according to the conditions set out in the law.

Of course, higher Social Security payments must be funded with higher taxes, but Nixon timed things so that the increase in payments started in October but the increase in taxes didn’t begin until January, that is, not until after the election! Nixon was thus able to shift benefits and costs so that the benefits hit before the election and the costs hit after the election.

To be fair, President Nixon’s policies were not unique or even unusual. Government benefits of all kinds typically increase before an election while taxes hardly ever do—taxes increase only after an election!

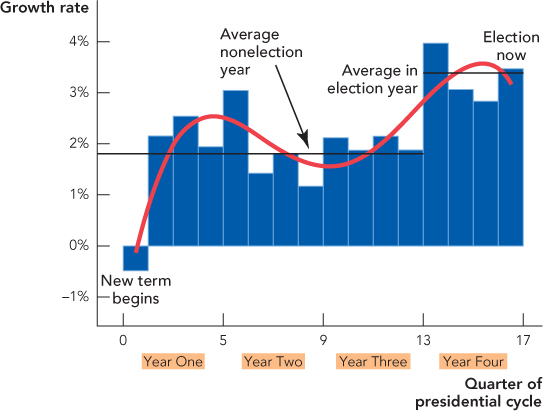

Using 60 years of U.S. data, Figure 21.2 shows the growth rate in personal disposable income in each quarter of a president’s 16-quarter term. Growth is much higher in the year before an election than at any other time in a president’s term. In fact, in an election year personal disposable income grows on average by 3.01% compared with 1.79% in a nonelection year. The difference is probably not due to chance.

Inflation also follows a cyclical pattern, but since voters dislike inflation, it tends to decrease in the year of an election and increase after the election. These patterns have been observed in many other countries, not just the United States. We also see political patterns at lower levels of politics. Mayors and governors, for example, try to increase the number of police on the streets in an election year, so that crime will fall and people will feel safer.

461

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 21.4

If voters are myopic, will politicians prefer a policy with small gains now and big costs later, or a policy with small costs now but big gains later?

If voters are myopic, will politicians prefer a policy with small gains now and big costs later, or a policy with small costs now but big gains later?

There are a limited number of things that a president can do to influence the economy, so presidents do not always succeed in increasing income during an election year. Presidents can influence transfers and taxes much more readily than they can influence pure economic growth. This is one reason why cyclical patterns are more difficult to see in GDP statistics than they are in personal disposable income.