A Free Market Maximizes Producer Plus Consumer Surplus (the Gains from Trade)

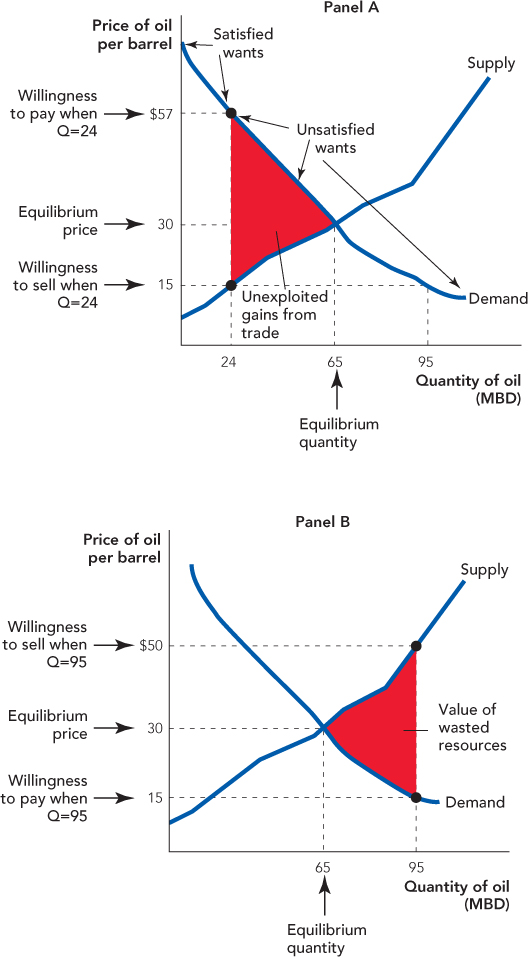

Figure 4.3 provides another perspective on the market equilibrium. Consider panel A. At a price of $15 suppliers will voluntarily produce 24 MBD. But notice that this is only enough oil to satisfy some of the buyers’ wants. Which ones? The buyers will allocate what oil they have to their highest-valued wants. In panel A of Figure 4.3, the 24 MBD of oil will be used to satisfy the wants labeled “Satisfied wants.” All other wants will remain unsatisfied. Now suppose that suppliers could be induced to sell just one more barrel of oil. How much would buyers be willing to pay for this barrel of oil? We can read the value of this additional barrel of oil by the height of the demand curve at 24 MBD. Buyers would be willing to pay up to $57 (or $56.99 if you want to be very precise), the value of the first unsatisfied want for an additional barrel of oil when 24 MBD are currently being bought. How much would sellers be willing to accept for one additional barrel of oil? We can read the lowest price at which sellers are willing to sell an additional barrel of oil by the height of the supply curve at 24 MBD. (Since sellers will be just willing to sell an additional barrel of oil when it covers their additional costs, we can also read this as the cost of producing an additional barrel of oil when 24 MBD are currently being produced.) Sellers would be willing to sell an additional barrel of oil for as little as $15.

Panel A: Unexploited gains from trade exist when quantity is below the equilibrium quantity. Buyers are willing to pay $57 for the 24th unit and sellers are willing to sell the 24th unit for $15, so not trading the 24th unit leaves $42 in unexploited gain from trade. Only at the equilibrium quantity are there no unexploited gains from trade.

Panel B: Resources are wasted at quantities greater than the equilibrium quantity. Sellers are willing to sell the 95th unit for $50, but buyers are willing to pay only $15 so selling the 95th unit wastes $35 in resources. Only at the equilibrium quantity are there no wasted resources.

50

The equilibrium quantity is the quantity at which the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied.

Buyers are willing to pay $57 for an additional barrel of oil, and sellers are willing to sell an additional barrel for as little as $15. Trade at any price between $57 and $15 can make both buyers and sellers better off. There are potential gains from trade so long as buyers are willing to pay more than sellers are willing to accept. Now notice that there are unexploited gains from trade at any quantity less than the equilibrium quantity. Economists believe that in a free market unexploited gains from trade won’t last for long. We expect, therefore, that in a free market the quantity bought and sold will increase until the equilibrium quantity of 65 is reached.

We have shown that gains from trade push the quantity toward the equilibrium quantity. What about a push for trade coming from the other direction? In a free market, why won’t the quantity bought and sold exceed the equilibrium quantity?

51

Now consider panel B of Figure 4.3. Suppose that for some reason suppliers produce a quantity of 95 MBD. At a quantity of 95, it costs suppliers $50 to produce the last barrel of oil (say, by squeezing it out of the Athabasca tar sands). How much is that barrel of oil worth to buyers? Again, we can read this from the height of the demand curve at 95 MBD. It’s only $15 (they get a few extra rubber duckies). So if quantity supplied exceeds the equilibrium quantity, it costs the sellers more to produce a barrel of oil than that barrel of oil is worth to buyers.

In a free market, suppliers won’t spend $50 to produce something they can sell for at most $15—that’s a recipe for bankruptcy.* We expect, therefore, that in a free market, the quantity bought and sold will decrease until the equilibrium quantity of 65 MBD is reached.

Suppliers won’t try to drive themselves into bankruptcy, but if they did, would this be a good thing? Even at the equilibrium quantity, buyers have unsatisfied wants. Wouldn’t it be a good idea to satisfy even more wants? No. The reason is that resources are wasted if the quantity exceeds the equilibrium quantity.

Imagine once again that suppliers were producing 95 units and thus were producing many barrels of oil whose cost exceeded their worth. This would be a loss not just to the suppliers but also to society. Producing oil takes resources—labor, trucks, pipes, and so forth. Those resources, or the value of those resources, could be used to produce something people really are willing to pay for—economics textbooks, for example, or iPads. If we waste resources producing barrels of oil for $50 that are worth only $15, we have fewer resources to produce goods that cost only $32 but that people value at $75. We have only a limited number of resources and getting the most out of those resources means producing neither too little of a good (as in panel A of Figure 4.3) nor too much of a good (as in panel B). Markets can help us to achieve this goal.

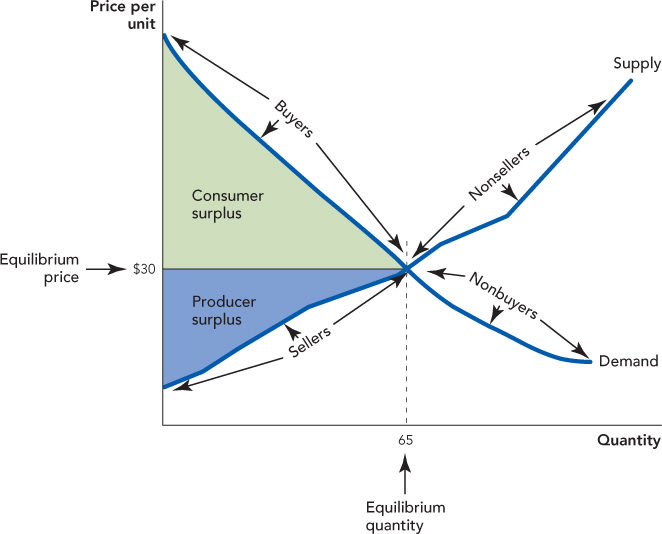

Figure 4.3 shows why in a free market there tends not to be unexploited gains from trade—at least not for long—or wasteful trades. Put these two things together and we have a remarkable result. A free market maximizes the gains from trade. The gains from trade can be broken down into producer surplus and consumer surplus, so we can also say that a free market maximizes producer plus consumer surplus.

Equilibrium and the Gains from Trade

http://qrs.ly/aw4ax6j

Figure 4.4 illustrates how the gains from trade—producer plus consumer surplus—are maximized at the equilibrium price and quantity. Maximizing the gains from trade, however, requires more than just producing at the equilibrium price and quantity. In addition, goods must be produced at the lowest possible cost and they must be used to satisfy the highest value demands. In Figure 4.4, for example, notice that every seller has lower costs than every nonseller. Also, every buyer has a higher willingness to pay for the good than every nonbuyer.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 4.3

As the price of cars goes up, which marketplace wants will be the first to stop being satisfied? Give an example.

As the price of cars goes up, which marketplace wants will be the first to stop being satisfied? Give an example.

Question 4.4

In the late 1990s, telecommunication firms laid a greater quantity of fiber-optic cable than the market equilibrium quantity (as proved by later events). Describe the nature of the losses from too much investment in fiber-optic cable. What market incentives exist to avoid these losses?

In the late 1990s, telecommunication firms laid a greater quantity of fiber-optic cable than the market equilibrium quantity (as proved by later events). Describe the nature of the losses from too much investment in fiber-optic cable. What market incentives exist to avoid these losses?

Question 4.5

Suppose that Kiran values a good at $50. Store A is willing to sell the good for $45, and store B is willing to sell the same good for $35. In a free market, what will be the total consumer surplus? Now suppose that store B is prevented from selling. What happens to the total consumer surplus?

Suppose that Kiran values a good at $50. Store A is willing to sell the good for $45, and store B is willing to sell the same good for $35. In a free market, what will be the total consumer surplus? Now suppose that store B is prevented from selling. What happens to the total consumer surplus?

Imagine if this claim were not true; suppose, for example, that Joe is willing to pay $50 for the good and there are two sellers: Alice with costs of $40 and Barbara with costs of $20. It’s possible just that Joe and Alice could make a deal, splitting the gains from trade of $10. But this trade would not maximize the gains from trade because if Joe and Barbara trade, the gains from trade are much higher, $30. Over time, both Joe and Barbara will figure this out, so in equilibrium, we expect Joe to trade with Barbara, not Alice. Thus, when we say that a free market maximizes the gains from trade, we mean three closely related things:

52

The supply of goods is bought by the buyers with the highest willingness to pay.

The supply of goods is sold by the sellers with the lowest costs.

Between buyers and sellers, there are no unexploited gains from trade and no wasteful trades.

Together, these three conditions imply that the gains from trade are maximized.

One of the remarkable lessons of economics is that under the right conditions, the pursuit of self-interest leads not to chaos but to a beneficial order. The maximization of consumer plus producer surplus in markets populated solely by self-interested individuals is one application of this central idea.