The Financial Crisis of 2007-2008: Leverage, Securitization, and Shadow Banking

Now let’s go back to the financial crisis and the collapse of Lehman Brothers, discussed at the beginning of this chapter. To give you an idea of what went on we will need to cover three ideas: leverage, securitization, and the shadow banking system. Let’s begin with leverage.

Leverage

As we have seen, consumers, firms, and governments all borrow. Borrowing can be a useful tool but it’s also possible to borrow too much. In the years leading up to the financial crisis, Americans borrowed more than ever before, especially in the closely related sectors of home mortgages and banking. It used to be common, for example, for home mortgages to require “20% down,” which means that a lender would lend at most 80% of the price of a house. On a $400,000 house, for example, a lender would agree to lend at most $320,000, requiring the buyer to put up at least $80,000 (20% of $400,000) as a down payment.

193

Owner equity is the value of the asset minus the debt, E = V – D.

The difference between the value of a house and the unpaid amount on the mortgage is called the buyer’s equity or owner's equity. Lenders want buyers to have some home equity because this protects them if the buyer defaults. If a buyer has $80,000 of home equity, for example, then even if the price of the house falls from $400,000 to $350,000 the bank could still recover all of its loan in a foreclosure. The buyer’s equity gives the bank a cushion.

In the 1990s and 2000s, however, lenders became convinced that house prices were unlikely to fall and they became willing to lend with much lower down payments, just 5% down or even less. Indeed, at the height of the housing boom in 2006, 17% of mortgages were made with 0% down! Many people thought that house prices would continue to rise so buying with zero down was a way to speculate. If house prices rose, they could borrow more or sell at a profit. If house prices fell, they could default and not lose any of their own money. Yet if house prices were to fall and buyers were to begin to default on their loans, the banks no longer would have a cushion.

The leverage ratio is the ratio of debt to equity, D/E

In finance, the ratio of debt to equity is called the leverage ratio. For example, if a buyer of a $400,000 house borrows $320,000 and spends $80,000 of her own savings, then her leverage ratio is  . If the buyer is able to borrow $360,000 to buy a $400,000 house, then the leverage ratio is much greater:

. If the buyer is able to borrow $360,000 to buy a $400,000 house, then the leverage ratio is much greater:  . Put differently, when the leverage ratio is 9, a buyer with $80,000 in cash can borrow $720,000 and buy a house worth $800,000. More leverage means that the same force (your cash) can be used to move (i.e., buy) bigger and bigger assets. As the financial crisis approached, house buyers were using more and more leverage.

. Put differently, when the leverage ratio is 9, a buyer with $80,000 in cash can borrow $720,000 and buy a house worth $800,000. More leverage means that the same force (your cash) can be used to move (i.e., buy) bigger and bigger assets. As the financial crisis approached, house buyers were using more and more leverage.

Home buyers weren’t the only ones leveraging more; so were banks. Lehman Brothers, for example, had assets worth hundreds of billions of dollars but it had borrowed hundreds of billions of dollars to buy those assets. Moreover, just like homeowners, in the 2000s banks had been borrowing more and more with lower and lower “down payments.” In 2004, for example, Lehman’s leverage ratio was around 20—which meant that for every $105 in assets that the bank owned, it had borrowed $100, leaving it with equity of just $5. A leverage ratio of 20 is already pretty high.

An insolvent firm has liabilities that exceed its assets.

Notice that if the value of Lehman’s assets were to fall by just 10%, it would have $94.50 dollars worth of assets and $100 dollars of debt, which means that a 10% fall in asset prices would make Lehman insolvent. An insolvent firm is simply one whose debts or liabilities exceed its assets (liabilities are legal debts plus other amounts owed, e.g. wage payments). Insolvency is usually followed by bankruptcy. Instead of reducing leverage in 2004, however, Lehman increased leverage so that by 2007 Lehman had an astounding leverage ratio of 44!9 At a leverage ratio of 44 even a small decrease in asset prices would bankrupt Lehman and in 2007 housing prices started to fall dramatically.

You might wonder why banks would ever want such a high leverage ratio. As we said, a leverage ratio of 44 means that even a small drop in asset prices would bankrupt Lehman but for exactly the same reasons a small rise in prices meant tremendous profits. When times are good leverage makes everything better. Moreover, when Lehman did well, Lehman’s managers received hundreds of millions, even billions, of dollars in bonuses and stock compensation. But when Lehman went bankrupt did Lehman’s managers go bankrupt? No. Most of them lost some money but they still ended up being very rich. Lehman’s managers wanted a lot of leverage because when things were going well the sky was the limit but when things went poorly most of them had limited downside risk.

194

Securitization

The second concept we need to understand is securitization. The seller of a securitized asset gets up-front cash while the buyer gets the right to a stream of future payments. Sometimes mortgage loans are “securitized,” or bundled together and sold on the market as financial assets. Banks may wish to sell or “securitize” their loans for several reasons. On the positive side, the bank gets more liquid cash, makes its balance sheet safer, and the securitized assets can be held as investments by institutions with a long-term perspective, such as pension funds. It’s a way that a lot of institutions can invest indirectly in the American economy. Alternatively, the critics charge that too often banks securitize because they made bad, sloppy, or under-researched loans in the first place and they wish to dump them on unsuspecting suckers somewhere else.

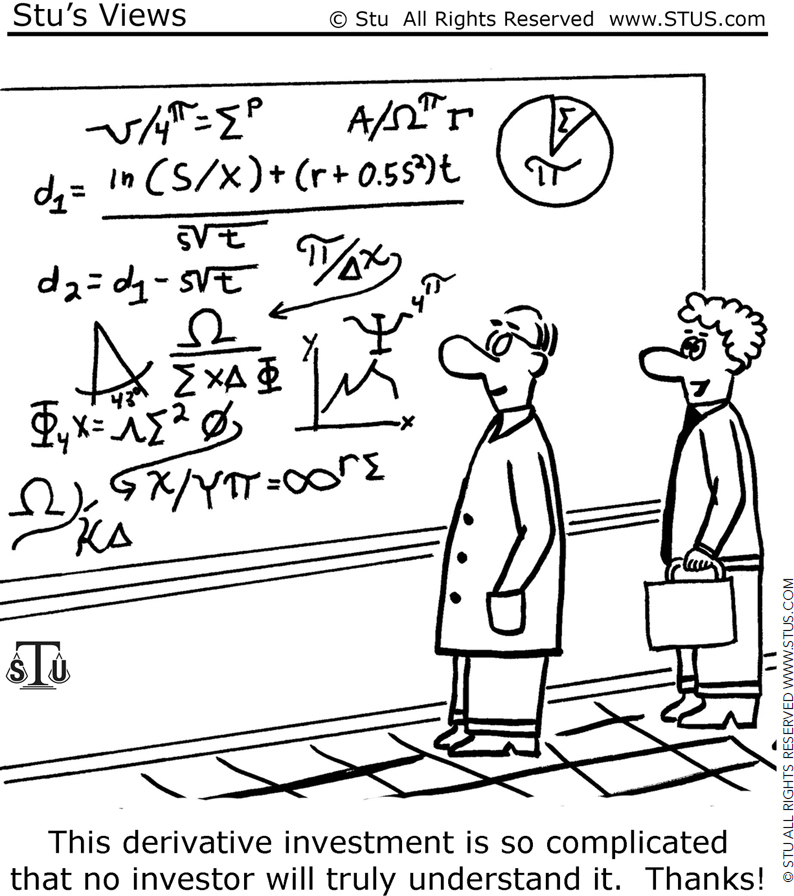

Once assets are securitized, the revenue streams from them can be sliced and diced and sold in all manner of ways. Mortgage securitization in the 2000s meant that dentists in Germany could easily invest in home mortgages in America. The increased ability to sell mortgages around the world was good for American home buyers because it kept interest rates low and it seemed good for investors who thought they were buying safe and secure assets. What could be safer than American homes? In reality, many of these securitized mortgages turned out to have had much higher risk than had been advertised. In part, some of the securitized bundles were sold on false terms or where the risk was obscured, in part the credit rating agencies performed poorly, and in part people simply estimated risk incorrectly by assuming that house prices would continue rising more or less indefinitely.

When housing prices started to fall dramatically in 2007, many people began to default on their mortgages. Overall delinquency (failure of payment) and foreclosure rates more than doubled. In parts of California, Florida, and Nevada more than 40% of the homes entered foreclosure. Remember that many buyers had only a little equity in their homes so as house prices fell they quickly came to owe more on their mortgage than their house was worth and many chose to default. As a result, the U.S. economy suddenly ended up in a situation where many banks and other financial intermediaries were holding loans and assets of questionable value. Moreover, since the banks themselves were highly leveraged, as the value of their assets declined, many banks quickly approached insolvency.

195

The Shadow Banking System

Now let’s turn to the last key idea, the “shadow banking system,” which has become a common term since the financial crisis. The traditional banking system can be represented by a commercial bank, the bank where you keep your checking account. Commercial banks fund themselves in large part through deposits from people like yourself and from businesses. These deposits are insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC; up to $250,000 and in practice often to an unlimited amount) and so a typical commercial bank always has some source of legally guaranteed funding. Sometimes commercial banks go out of business but because of insurance, depositors don’t feel that they need to yank out their money at the first sign of trouble.

An investment bank is a bit different from a commercial bank. In a commercial bank the money comes from depositors. In an investment bank, the money comes from investors. Deposits are government guaranteed but investments are not, so investors are much more prone to panic and to withdraw their short-term funding in times of crisis. Investment banks, such as Lehman before its demise, are part of what has been called the shadow banking system. In addition to investment banks, the shadow banking system includes hedge funds, money market funds, and a variety of other complex financial entities. What unites the shadow banking system is that these financial intermediaries act like banks—they typically borrow short term to lend and invest in longer-term and often less liquid assets—but they have traditionally been less heavily regulated and monitored than banks and unlike deposits, their short-term sources of funds (loans from investors) are not government guaranteed.

The shadow banking system got its name because it grew up in the shadow of the traditional banking system and for a long time most regulators and policymakers were unaware of its importance. But by the mid-1990s the shadow banking system was lending as much as were traditional banks and at its peak in 2008 the shadow banking system lent $20 trillion, considerably more than did traditional banks.

Fire Sales The financial crisis can be understood as a run on the shadow banking system similar in many respects to bank runs during the Great Depression. Think of an investment bank as being funded by a variety of short-term and long-term loans. If investors fear that the institution will go bankrupt, each lender will seek to withdraw his money or refuse to renew the loan, as soon as possible, just as depositors rush to withdraw their money from failing banks of the traditional kind. The short-term loans disappear most quickly because they are rolled over every night or otherwise on a very frequent basis. Without the short-term loans, the investment bank no longer has enough operating funds and it is forced to sell off assets quickly in what is often called a “fire sale.” Furthermore, if enough firms find themselves having to sell assets, fire sales can quickly get out of control. The selling of assets by one financial institution can push prices lower, which pushes another institution close to insolvency, causing it to have to sell assets, which pushes prices even lower—if the process goes on too long, a fire sale can turn into a fire storm.

196

Many of the participants in the shadow banking system were highly leveraged. As noted, shortly before its failure, Lehman Brothers had a leverage ratio in the range of 40 and many other major banks were not far behind. As we’ve already explained, a high leverage ratio puts a bank in a very vulnerable position. When leverage ratios are high, a small decline in asset values can wipe out the equity cushion of the bank and push the bank into insolvency. It was the justified fear of this outcome that caused the short-term lenders to flee from the funding of Lehman, thereby triggering its financial meltdown.

Moreover, because mortgages had been bundled and sold many times over in different combinations, and because many bets had been made on their prices, no one knew exactly which financial institutions faced the biggest losses. As a result, it became increasingly less certain which institutions were profitable and which were due to go bankrupt. No one wanted to lend or invest in banks and other intermediaries that might have significant exposure to mortgage-backed assets on their books. Why lend or invest in a bank when the bank might be gone tomorrow? Investors also became wary of any institution that lent money to potentially troubled banks, even if that institution did not itself hold mortgage-backed assets.

Putting it all together, the high leverage of homeowners meant that defaults increased rapidly as house prices fell and the higher default rate on mortgages created losses for banks. Because these banks were highly leveraged, many of them were quickly pushed towards insolvency. The shadow banks in particular relied on short-term funding, which unlike deposits was not guaranteed so people who lent to shadow banks were anxious to stop lending once they feared a firm might go bankrupt. The bundling and division of mortgages and the many side bets made on securitized mortgages were so complicated, however, that it wasn’t always clear who owned what or who faced the worst losses. Investors became reluctant to lend to any financial institution. Finally, when financial intermediaries can’t get new funds, the bridge between savers/lenders and borrowers collapses. Indeed, the reluctance of investors to lend to shadow banks meant that their lending was forced to shrink so that by 2010 shadow banks were lending just $16 trillion—a massive loss of $4 trillion in lending since 2008. It was this credit crunch that threw the entire economy into disarray.

CHECK YOURSELF

Question 9.11

How do usury laws (controls on interest rates) cause savings to decline?

How do usury laws (controls on interest rates) cause savings to decline?

Question 9.12

Besides decreasing the number of banks, how do bank failures hinder financial intermediation?

Besides decreasing the number of banks, how do bank failures hinder financial intermediation?

Question 9.13

How does awarding bank loans by political criteria or by cronyism (to your pals) affect the efficiency of the economy?

How does awarding bank loans by political criteria or by cronyism (to your pals) affect the efficiency of the economy?

It’s now considered a general problem that the short-term loans for the shadow banking system can flee rapidly in times of crisis, causing some financial markets to shut down and credit to freeze up. Some commentators have suggested that the government guarantee loans to the shadow banking system in times of crisis, but that puts a potentially large liability on taxpayers and it is politically unpopular. Nonetheless, the U.S. government already has taken some steps in that direction. After the trauma of the Lehman Brothers failure, the insurance company AlG was on the verge of failure, but this time the Federal Reserve, led by Bernanke, stepped in and took over majority ownership of the company and guaranteed its debts. They didn’t want to repeat the credit market freezes that followed the collapse of Lehman. New financial regulations are now bringing the shadow banking system “out of the shadows” and regulating these financial intermediaries in ways similar to traditional banks. A key idea has been to require banks of all kinds to hold more equity, that is to reduce the amount of their leverage. It remains to be seen how effective and how costly these new regulations will be.

197